Cinzia Oliva, a textile restorer from Turin, Italy, who specializes in mummy wrappings, puts the finishing touches on restoring the mummy Ny-Maat-Re in the Vatican’s Museum’s collections in this endated photo.

The art treasures of the Vatican — from all ages and of many cultures — are to be found in 10 pontifical museums, often erroneously referred to as the “Vatican Museum” in the singular. Less well-known than the Raphael Rooms, Borgia Apartments and the world’s largest collection of ancient Greek and Roman art, but nonetheless one of the finest in Europe, is the Vatican’s Egyptian Museum, officially known as the Gregorian Egyptian Museum.

This assembly of ancient Egyptian objects was begun by Pius VII (1800-1823), but not officially founded until 1839 by Pope Gregory XVI (1831-1846), a conservative propagandist of the faith, whose interest in ancient Egypt was more biblical than archeological. Opened on February 6, 1839 to celebrate the eighth anniversary of Gregory’s election, the Vatican’s Egyptian Museum was originally arranged by Barnabite Father M. Luigi Ungarelli, one of French Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion’s first students and one of Italy’s first Egyptologists.

What makes this collection different from all others is its provenance. Many of its artifacts came to Rome in ancient times. The Roman emperors were fascinated by ancient Egyptian culture with its deification of the pharaoh, so they brought back artifacts to Rome as spoils of war, but also for their artistic beauty. It could be said that the ancient Romans had already selected the Museum’s unofficial core collection. Then they had “Egyptianized” objects made in situ. Instead, almost all other Egyptian collections worldwide procured their finds in Egypt in the 19th century.

In short, some of the Museum’s artifacts date from ancient Egypt and were brought to Rome by the ancient Romans; some were made in Rome in Egyptian style during Imperial times; others, dating to ancient Egypt, were bought by the Popes, before and after the foundation of the collection; and still others were donated during the last century.

By using imaging technology and other state-of-the-art lab tests, Vatican experts discovered it was a fake mummy made up of a few human bones from the Middle Ages wrapped in ancient bandages. Such fakes were often passed off to unsuspecting European collectors during the so-called “mummy-mania” of the 19th century.

One such artifact, one of the Museum’s most-prized objects which was given to Pope Leo XIII (1878-1903) in 1903 by the art patron and collector Emile Guimet, is the so-called “Lady of the Vatican.” It’s a fragmentary painted-linen funerary shroud with a full-length effigy of a young woman. It dates to the Roman period in Egypt, when it was used to wrap the young lady’s mummy inside her coffin.

Speaking of mummies, in 2007 Dr. Alessia Amenta, Egyptologist and, at the time, the newly-appointed curator of the Vatican Museums’ Near Eastern and Egyptian Department, which includes the Gregorian Egyptian Museum, spearheaded the “Vatican Mummy Project.” Its goal was and still is to study, restore and best conserve the Museum’s nine complete mummies (two of the seven adults are on display) and 18 body parts made up of heads, hands, and feet, using the latest scientific interdisciplinary techniques, now an integral part of “artifact” restoration and conservation. Amenta met with Lucy Gordan, Inside the Vatican’s culture editor, at the beginning of February to discuss her “Mummy Project” and its discoveries.

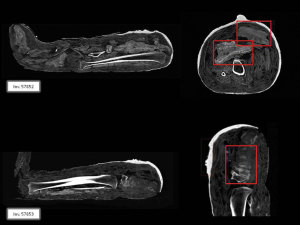

The Project’s non-invasive exams (as summarized in an article by Carol Glatz for Catholic News Service, January 18, 2015) include: “X-ray florescence and electron microscopes to tabulate what chemical elements were contained in all the materials; carbon dating to determine the age of the different materials; infrared and ultraviolet analyses to reveal colors and images otherwise not visible to the naked eye; gas-chromatography/mass spectrometry to identify the presence of organic compounds; and CT scans to create 3D images of the contents inside.” Most of these exams have been carried out at the Vatican Museums’ own Diagnostic Laboratory for Conservation and Restoration under the guidance of its director, Ulderico Santamaria, and his assistant, Fabio Morresi. The genetic analyses have been done at Bolzano’s EURAC-Institute for Mummies and the Iceman, directed by Dr. Albert Zink.

Amenta’s choice of which mummy to examine first and then restore was based on one mummy’s serious state of degradation: poorly embalmed, the linen bandages under the back rotted away, and the spine and ribcage collapsed. After two years of testing begun in 2009, the 3D CT scan revealed that this one — a “she” mummy, given to Pope Leo XIII in 1894 and identified from the hieroglyphics on “her” three-dimensional painted coverings (made of plaster and linen and known as cartonnage) as “the daughter of Sema-Tawi” named “Ny-Maat-Re” and never before “unwrapped” — was clearly a man. He was from the Fayoum Region, had lived sometime between 270 and 210 BC, had died at 25/30 years old, and had suffered from Schmorl hernia.

“We hope to display this restored mummy soon,” Amenta told me, “together with a video about ‘his’ restoration. The three mummies still in our storerooms are in poor condition and still need to be restored.”

The second mummy to be examined does belong to a young lady, probably the one once wrapped in Guimet’s priceless shroud. The wrappings around her face and neck had been ripped or cut open long ago by someone who was looking for the precious jewels and gold often placed under the wrappings or around the faces of mummies. Since her woven wrappings were cut clean, the experts were able to make an in-depth “stratigraphic” study of the pattern of her bandages and her several shrouds and thus her embalming procedure. This is particularly significant because the techniques for wrapping the bandages around mummies changed over the centuries.

Research to date shows that mummification was carried out for two millennia, beginning in the Old Kingdom (2649-2152 BC) and continuing through the Late Period (712-332 BC). It declined during the late Ptolemaic (c. 200-30 BC) and Roman periods and stopped altogether with the introduction of Islam in the 7th century AD.

It shouldn’t be forgotten that a mummy is unlike any other museum treasure, no matter how priceless, because it was once a living person. Thus it has special needs for storage and exhibition. Especially important is climate control to prevent decay and best preserve its mummified state. Otherwise a lot of irreplaceable information is lost because the mummy’s proteins and DNA degrade. When it comes to research, mummies are a treasure-trove of valuable information about daily life, customs, health, art, architecture, mathematics, and religious beliefs in ancient Egypt. For example, discovering that a mummy suffered from an illness still prevalent today allows us to trace its evolution over time.

The test results on the next two mummies or “mummiette,” as Dr. Amenta calls them, examined during 2014, were revealed on January 22 by Professor Antonio Paolucci, Director of the Vatican Museums, and Drs. Amenta, Santamaria, and Morresi, during a spell-binding conference entitled “A Case of Mummy-mania: Scientific Investigation [Forensic Science] Solves An Enigma.” The provenance of both of these approximately 2-foot-long “mummiette,” which were probably donated in the late 19th-century by a private collector, is so far nowhere to be found in the Museum’s records. Up to a year ago, due to their small size and weight, they were believed to be mummies of children or animals, possibly falcons. “They could also have been so-called ‘pseudo-mummies’ — a bundle of wrappings and other materials — sometimes even a few bones,” Amenta explained to me, “that were used in ancient times to substitute a missing or incomplete body of a dead loved one. The transfiguration and ‘divinization’ of the deceased was essential for the ancient Egyptians. Some kind of physical form had to be designated to be able to send the deceased ‘into another dimension’ after death.” Instead, all the scientific data revealed these “mummiette” to be 19th-century fakes.

Radio-carbon dating confirmed that their bandages or wrappings were indeed ancient, dating to c. 2000 B.C., but coated with a resin that is only found in Europe. In addition, radio-carbon dating on one of the bones protruding from the bandages of one of the “mummiette” confirmed that it dated to the Middle Ages. That these two “mummiette” were crafted in England or Wales, probably by the same forger, can be confirmed by the presence of tin under the painting layer of the face as a sort of “meccatura,” for tin was a British (more accurately Welsh, because tin cans were born in Wales) monopoly until the end of the 19th century.

“It is not a scandal to discover fake mummies in a Museum collection,” continued Amenta. “They are a well-defined category. Forgeries are part of art history. The industry of churning out fake mummies was widespread, as I already explained on January 22, even in the age of the pharaohs, which makes them a fascinating offshoot field of study. I know of some 40 other fake ‘mummiette’ in Europe’s Egyptian collections or Natural History Museums. To cite a few, in Italy there are two in Florence, one in Milan, four in Turin, and one in Venice. There are also two in Lithuania, four in Vienna, three in Berlin, and only one in the United States, in the Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C. They were donations from private collections. Many ended up in natural history, rather than art, museums because they were believed to be animal mummies. The greatest number is not surprisingly in the United Kingdom, in Bolton, Bristol, Liverpool, and the British Museum.”

The first episodes of mummy-mania date to Roman Imperial times. At that time, the demand for mummies to bring home primarily as military booty was already greater than the supply. Later, during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, mummies, hopefully authentic but not always, were in high demand because they were burned and used as a powder in apothecary potions for various ailments. “The market was so huge,” said Amenta, “that two pounds of mummy dust during the Renaissance cost the equivalent of $17,000 today.”

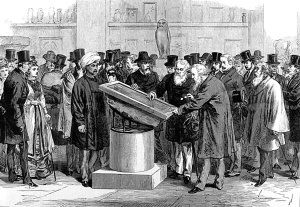

Creating fakes reached a high point in the 1800s when mummy-mania began in Europe after Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt in 1798 and Champollion’s deciphering of the Rosetta Stone in 1822. Elite Europeans, particularly British adventurers on the Grand Tour, brought them home as souvenirs and then invited their friends to “unwrappings,” a very popular “afternoon tea spectacle,” which, of course, could have a devastatingly disappointing ending if there was no mummy in the bandages. However, just like the bandages of the Vatican’s “mummiette,” part of a mummy could be authentic and sold off to forgers even if the rest were fake.

In addition to the “Vatican Mummy Project,” the Vatican’s Egyptian Department, together with the Louvre, the Center of Research and Restoration of the Museums of France, the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, and the Egyptian Museum in Turin, is carrying out “The Vatican Coffin Project.” The Vatican hosted the “First Vatican Coffin Conference” from June 19-22, 2013 — the first conference on Egyptology at the Vatican. This was an initiative to study the construction and painting techniques of coffins during Egypt’s so-called Third Intermediate Period (990-970 BC). The Gregorian Egyptian Museum houses 23 such coffins.

An illustration in the London News of orientalists inspecting the Rosetta Stone during the International Congress of Orientalists, 1784.

“It was the first time internationally renowned scholars compared their research on the period’s coffins, which reflect the clerical culture of the increasingly powerful Theban high priests,” Amenta told me. “No in-depth, comprehensive studies have been done on the period’s wood construction and painting techniques, and no ancient Egyptian texts have been found explaining the process.”

A “Second Vatican Coffin Conference” is scheduled to take place in 2016.

At the end of January 22’s conference, Dr. Amenta announced a new collaboration dating from July 2014 between the Vatican Museums and the Egyptian Museum in Turin.

The team of the Vatican Coffin Project is presently restoring Turin’s elaborately-painted anthropoid Coffin of Butehamon, a royal scribe during the 21st dynasty (Third Intermediate Period). Work is to be completed in time to put the Coffin back on display in a new room dedicated exclusively to coffins when Turin’s Museum inaugurates its new state-of-the-art rooms and displays on April 1.

Facebook Comments