Purchase the book

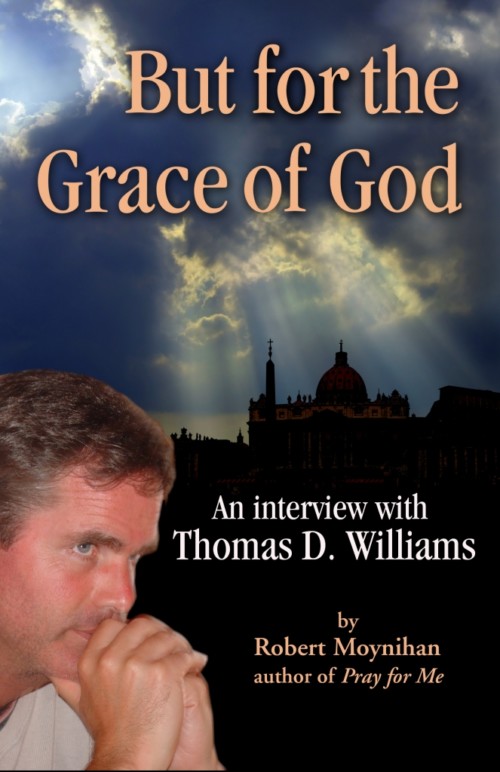

As a leader of the Legionaries of Christ, Father Thomas Williams was a leading moral theologian in Rome. But two years ago, it became public that he had fathered a son ten years ago. He first stepped down from all his functions as a Legionary priest, then left the priesthood to take care of his son and to marry the child’s mother. Today the three live in Rome.

Is there life after disgrace? In May 2012, the Catholic world was shocked by the revelation that Father Thomas Williams, perhaps the best-known Legionary priest and a regular presence on television and in the media, had fathered a child almost ten years before. Some people were appalled, some reached out to him in support, others simply chose to pray in silence.

A year later, after a period of discernment, Williams announced that he had applied to the Holy Father for a dispensation from his priestly ministry to care for his child and the child’s mother. On receiving it, he was married in the Church. He is now living in Rome.

I had been friends with Williams for 20 years. I wondered what this ordeal had cost him, and what his plans were for the future. He had been a public voice for the Catholic faith for a quarter century in an increasingly secularized society. Would be continue to be a moral theologian? Or would his personal conduct, struggles and sufferings make it impossible for him to speak publicly about Church matters? I contacted him and suggested that, once the waters had settled a bit, we should conduct an interview.

Many of us have heard a good deal about Williams, but in the last two years we have heard very little from him.

In this interview, he tells the story of his entrance into the Legion, his closeness with the founder, his departure from the Legion and the priesthood, his love for his son (a Down’s Syndrome boy named Joshua), and for the wife he married on December 7, Elizabeth Lev.

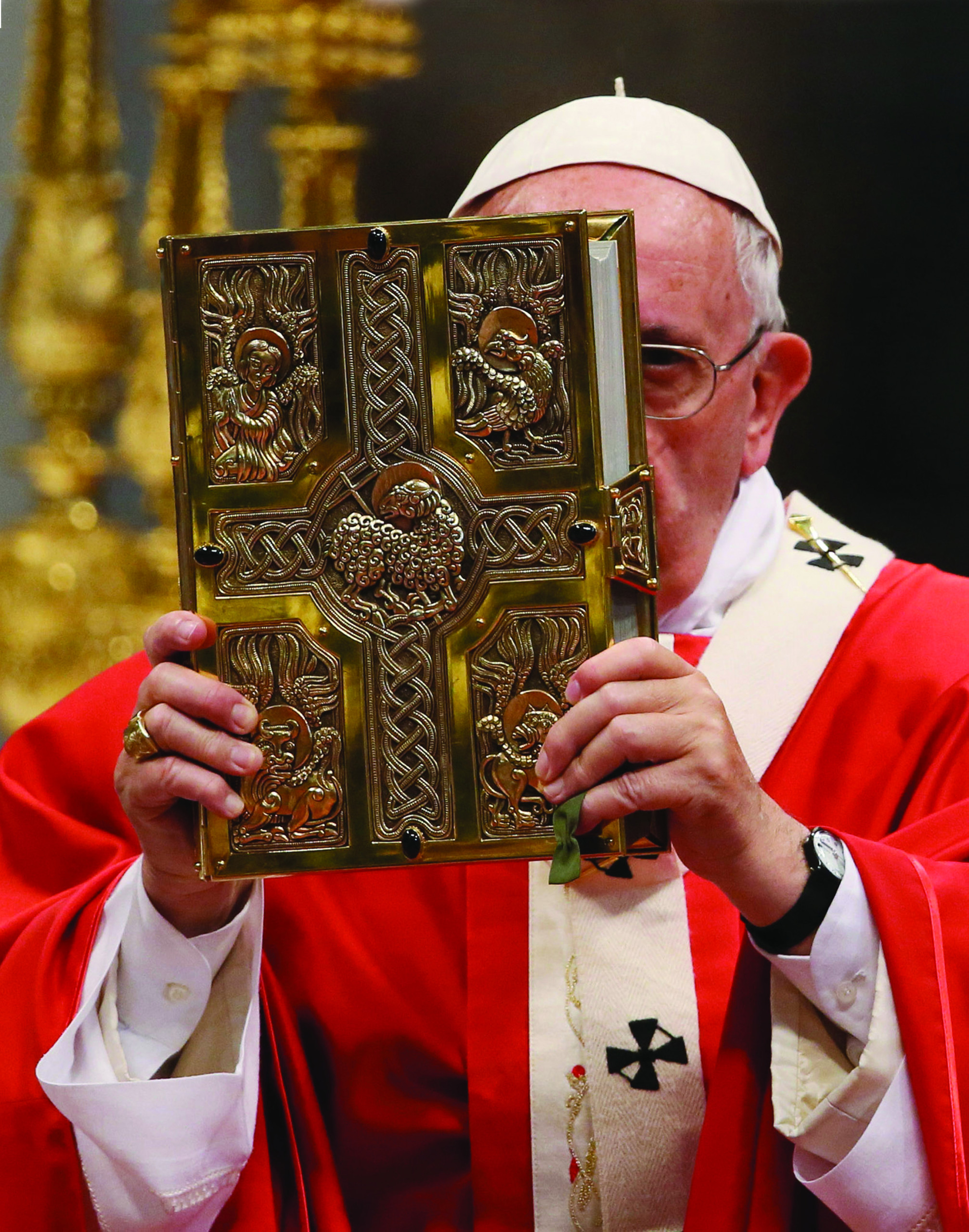

As Christians, we believe in the power of God’s merciful love. In the spirit of Pope Francis, and of Jesus, I invite readers to read these words with a merciful heart. We are all sinners, but our struggles and the experience of God’s forgiveness can make us better, even more committed, Christians. Thomas Williams has been an influential voice in the English-speaking Catholic world. Perhaps these events will be the catalysts to a new and important period in his life as a disciple of Christ.

Thomas Williams.

Interview with Williams

Thomas Williams has left the priesthood and has been laicized by Church authorities. On December 7, 2013, in New York City, he was married to Elizabeth Lev, the daughter of Dr. Mary Ann Glendon, former US ambassador to the Vatican. The two of them live together with their son, Joshua, in an apartment in Rome not far from the Vatican. Below are brief excerpts from a conversation between Robert Moynihan and Thomas Williams that began in the late summer of 2013, several months before the wedding, and continued up to the present. The complete interview is available on the web for downloading at the insidethevatican.com website.

Is there something eternal about a sin, even if the sin is forgiven?

Williams: I think the devil would like us to believe that. He seems to have a kind of forked approach, a two-pronged approach: The first is to diminish sin, and make it look attractive and unimportant. So he says, “Go do that. It doesn’t really matter, it’s not that big a deal.” And as soon as we’ve committed it, as soon as we’ve listened to his lies and fallen, he takes the exact opposite approach, and he says, “I can’t believe you did that… You are so wicked, you are so evil, give it up. Stay down. Don’t get up. Don’t think that God will forgive you. You are just rotten to the core.”

I was wondering whether I should even do this interview. I would love to forget my past and pretend that it never happened. I really wanted to just lie low and hope people would forget about me. But I have a deep sense that God wants more of me, and that I am called to bear witness to his mercy. And that means also owning my own sin.

God’s approach is the exact opposite of the devil’s. God, before we sin, is saying, “Don’t do that. This is serious”; “Believe me, you don’t want to go there.” And as soon as we fall, he takes the opposite approach and says, “Get back up. Here I am. I’m ready to embrace you. We can make this right.”

Father Thomas Williams’ book, Knowing Right From Wrong.

Did you know well the founder of the Legionaries, Father Marcial Maciel Degollado?

Williams: I knew the founder very well. I lived in the same community with him for almost ten years in the 1990s, which I considered at the time to be a real privilege. I had met him years earlier but I only got to know him later. He used to travel a lot, so I only saw him from time to time, but when he was in Rome we would often have meals together. He always impressed me, which made it so shocking when the accusations about him turned out to be true.

Do you remember any conversation?

Williams: There were so many, that it’s hard to pinpoint one. What I remember most is how single-minded he was. When he would talk about the Church, when he would talk about Christ, he was so passionate. He came across as loving the Church so deeply and wanting to do things for the Church so much, that to this day I have a hard time believing that he was not sincere, or that that was an act. I don’t understand it and I can only assume that he must have suffered from some psychological pathology that made this duplicity possible. The whole thing is completely mysterious to me. And I saw him do things for the Church and work very hard and make sacrifices for the good of other people. I remember a religious sister telling me one day that Fr. Maciel had found out that she needed a serious operation but couldn’t afford it, and that Fr. Maciel had gone and paid for it himself.

So what I remember mostly about the conversations was that they were always about spiritual topics. He loved to talk about spiritual things and if people talked about more mundane things he would find a way to turn the topic to spiritual things. He would elevate the conversation. We all believed in him, and his love for Christ was contagious. Again, that’s why everything was so absolutely confusing and still is to this day. I don’t know how to put the realities together of what I experienced and what we learned about him later.

There were starting to be public allegations by 1997. Do you think that the allegations, which you certainly didn’t believe were true… but did they play any role in your own spiritual life?

Williams: I don’t know. I didn’t believe the allegations when I heard about them in 1997. They seemed ridiculous to me and I dismissed them. I saw them simply as being a persecution or a cross. You know, people say things about people all the time and I had all sorts of reasons why people could be saying things that weren’t true, and so I simply dismissed them.

That’s why I defended him, even publicly. I simply couldn’t get my mind around the idea that he could be anything other than what he seemed to be. It didn’t fit.

So when the accusations first came up about him, I was in absolute denial. The reason that it was so hard for me to believe what was said about him was because it was completely contrary to the experiences that I had had of him. It seemed to go against everything that I had not only believed about him, but actually seen. There were so many examples like this. Also, we had been told that he had been investigated in the 1950s and had been found completely innocent, so these newer accusations seemed like more of the same.

(Questions about his leaving the priesthood)

Can you say that you fell in love?

Williams: Yes. I can say that I fell in love. Love has many expressions and many forms, and some are proper in certain moments, in certain places, in certain conditions, and some are improper. Love in itself is always good and is always of God. To love is always proper.

But I had freely promised God that I would love in a different way, and not in a romantic way. There are ways of expressing love that are not in accordance with the way that love should be expressing itself, and so the problem is not in loving, but in expressing that love in ways that are improper, or allowing a love to grow that is wrong for your state in life. The same way you would say to two young people that are in love but not married, there are ways to express that affection, there are ways to express that love which are proper to your state, and there are ways that are improper.

That’s where the sin was, in the way of expressing that and in allowing a romantic love to grow in my heart, rather than a priestly love.

Did you try to kill that love?

Williams: No. I did not try to kill the love. My big mistake was failing to order it better, with God’s grace, to my state in life.

Again, God does write straight with crooked lines, and in the end, this will all be to his glory, but for my part, what I did was terribly wrong and cannot be justified in any way. What God is making of this is something great and beautiful, though it began with wrongdoing on my part.

At the time when you knew that you were going to have a child, what were your thoughts?

Williams: Strangely, I was never sad about that. And I say it’s strange because even from a very human psychological standpoint, I never thought, “Oh no, that’s terrible.” From the very moment that I knew I was going to be a father, I thought it was a huge gift. I was overwhelmed with joy, honestly. And obviously as a Catholic I’d always been very, very pro-life and I also saw it as an opportunity to embrace life. I saw it as just the way that I’ve always seen life. Where there is life, God is always present; God is always willing that life. Even though he doesn’t necessarily will every action, he wills all life that is, and I embraced it as a gift of God. When I found out that my son had Down’s Syndrome, my first thought was that I wasn’t worthy of this gift. I thought he only gave special needs children to especially holy and generous people. I didn’t feel worthy. I felt deeply humbled by this gift.

Elizabeth and I decided to name our son Joshua, because it is another form of the name of Jesus. Joshua means “Yahweh saves” and we knew that his presence in our lives and in the world would manifest the presence of Jesus, and God’s saving love.

Some years passed by before you made this public and stepped aside from your priesthood. Was Elizabeth agreeing with that or did she ask for other things?

Williams: She never asked for anything. She wanted me to do what I thought I should do, and she affirmed my vocation. Neither of us wanted to hurt my priesthood in any way, and especially, we did not want to bring scandal to the Church. That has now happened, obviously, because this has become public, but we were really hopeful that it wouldn’t.

Williams and his son.

What was your attitude toward Joshua and Elizabeth during these years?

Williams: The priest confessor that I went to after this happened told me, “Don’t you walk away from this. Don’t you think that you can just say, ‘God, I’m sorry,’ and continue your life as if nothing happened. You have natural obligations to your child and to his mother. You have to be present in his life, to be a moral and a material support, to support them in every way that you can that is compatible with your priesthood.”

And I sought to do that over ten years. I was very present in their lives and tried to be, as best I could, a father to Joshua, given the circumstances I was living in.

Were you living a double life?

Williams: I don’t know the answer to that question. I’ve thought about it a lot, I’ve prayed about it a lot. There certainly were aspects about it that were double, in the sense that there were two sides to the coin. I was trying to live my priesthood as faithfully as I could and trying to be a good priest, and I was trying at the same time to be very present in the life of my son and his mother as I had been told to do in no uncertain terms. I just tried to balance those two realities as best I could in a single life.

Right now, now that this has all come out, I do feel a liberation of spirit. The fact that everybody knows is a great relief to me because there’s a burden of secrecy, there’s a burden of not wanting people to find out something, and now that that’s no longer there, I actually breathe much freer, and I find that to be a very joyful experience.

But what were you thinking while writing books about morality when you were so aware of your own moral failings? Isn’t that hypocrisy?

Williams: Many people have criticized me for this, and I can understand why. It seems strange and upsetting to have a priest preaching or writing about principles that he has failed to live up to. I think that I was wrong to carry on such a public ministry when there was a danger of such scandal. I did of course believe and still believe everything I wrote and preached. I knew well where my own failings were and I tried to judge myself by the same principles that I was announcing to others. I knew I had done wrong and I repented of it.

I have always understood hypocrisy as the acceptance of a double standard—one for oneself and one for others. It implies an insincerity in what we pretend to believe. But none of us perfectly lives up to his moral code in everything, and that doesn’t make us hypocrites. Our ideals will always be higher than our conduct. Personally I think that our failures shouldn’t make us afraid to proclaim a message that we believe in, even if we aren’t perfect models of it in practice. When we fall, we are called to repent, beg God’s forgiveness and convert. But we aren’t called to roll over and die. If we lower the ideals of the Gospel to match our own moral poverty, then we do an injustice to God.

As a priest, I was called to preach the Gospel, including the moral dimensions of that message. Moreover, I was trained as a moral theologian and that was my area of expertise. I had a choice: either stop preaching and teaching because I was a sinner, or continue preaching and teaching, with a special awareness of my own unworthiness as a bearer of that message and my own need for God’s mercy. This is what I tried to do. St. Paul said that Christians are like clay jars that contain a precious treasure—we will never be worthy vessels of the Good News that we announce. Still, I should have done this in a less public manner and I am sorry I did not.

There is a delicate question which you do not have to answer, but did you make an agreement with Elizabeth that you would return to your priesthood and in some way break off the relationship with her, and then carried that forth until it became impossible? What was happening in these ten years?

Williams: I never sought to break off relations with Joshua and his mother, and was told not to do so. So I never saw that as something that God wanted, ever. I never even considered it. What I did try to do was live that relationship in a way that was proper. I tried to live it in a way that was pleasing to God, but I never wanted to break it off.

Thomas Williams on his wedding day.

Was that difficult?

Williams: Oh, it was incredibly difficult, and in the end, it was impossible. In early 2012, Cardinal De Paolis, the papal delegate for the Legionaries who was fully aware of my situation, put me into a dilemma where I had to make a choice. He said, “You must choose one or the other, that you will either be an active father to your child or you will be an active priest.” He said, “You may not do both.” He told me I could either walk away from my son forever and live my priestly ministry, or devote myself to Joshua full-time.

My superiors asked me to make a public statement about my situation, and then I began a year of very, very intense discernment, knowing that I had to do one or the other. It was such a truly difficult period because I knew that I couldn’t do both things and I really didn’t know what God wanted me to do.

How did you live out that year? You said you went to a private retreat and for eight days you sought clarity as to what decision you should take in your life. You went into that, you said, believing that probably you wouldn’t receive clarity, but you did receive clarity. Can you describe it?

Williams: I did. For the first nine or ten months of the year, I prayed, and I was living with my parents, and it was a very, very quiet, semi-monastic environment because my parents are 80 years old and it was very, very, very quiet compared to the active life that I’d had before. We had daily Mass together and it was a very slow, peaceful little life.

During this time I was preparing to do spiritual exercises, an eight-day silent retreat, since I knew I needed that time of more intense discernment. I found a fantastic priest who was willing to do this with me. So we went together to the Benedictine Monastery of St. Leo’s in Florida. This priest generously gave me eight days of his life. It was just he and I on this retreat, and he prepared the directed meditations for me based on my situation to help me.

I went into the retreat pretty convinced that I was going to come out of it the way I went in. I figured that when it was over, I would just have to make some decision. “When this year is up,” I said to myself, “I’ve got to do something, and maybe God’s not going to tell me what that should be, and I don’t deserve that he tell me what it should be, so that’s fine, and I’ll just have to hope that I can make the best decision possible and that he’ll bless me afterward and things will be OK.”

So I really wasn’t expecting any sort of revelation, I wasn’t counting on God to speak to me in any clear way. I just thought it would be a prayerful time and then we’ll see what comes next. I knew I had to try to do my part. What really surprised me was that on the second day of the retreat, I had the first of two very, very powerful experiences of prayer where God really did speak to me in a way that I don’t know that I ever experienced earlier in my life. I had years and years of daily prayer, but something so direct was an immense gift.

In the first one, it was about my priesthood, because I was really going back and forth… I have a child and at the same time, I have a vocation to the priesthood, and in a way they seem to be two completely incompatible goods. And one of them was going to be lost. How can this be? I can’t give up the priesthood which God called me to, and which he created me for, and it’s a sacrament. And at the same time, there’s a child who depends on me. I’m his father, and he has a right to my presence. He has a right to my attention. He has a right to my protection. He has a right to my providence. And I thought to myself, “There is no solution to this.”

And one day on the retreat, there was a woman there at breakfast in the morning who had written a song. She’s a songwriter/singer and the song uses the words from Scripture, “You are a priest forever in the order of Melchisedek.” So I went out after we had breakfast, and started thinking, “Well, God, all right. I think maybe this is a sign that you’re telling me that your priesthood trumps everything else.”

And it was as if… I didn’t hear a physical voice, no apparition, no … but immediately, it was as if I heard a voice inside me simply say, “Don’t mistake my meaning. That is a statement of fact. It’s not a command I’m giving you, I am telling you that you are a priest forever. And whatever you do, if you take care of your child, you will do so as my priest. I will forever look at you as my priest. Wherever you are, whatever you’re doing, nothing can take that away. What I’m telling you is that your priesthood is a good that cannot be lost—and that is not going anywhere. You will not, you cannot give up your priesthood. The Church cannot take away your priesthood. You are a priest forever. I am affirming a fact about who you are in my sight, and the way I love you as my priest.”

And I felt like a ton of bricks had been lifted off my shoulder, because I suddenly saw for the first time a glimmer of light where I thought I could actually fulfill my obligations of love and justice toward my child but then at the same time nothing is lost eternally, in the sense that my priesthood is intact.

And I know that there is something huge lost in not being able to practice the ministry of my ordained priesthood, but at the same time, God was telling me, “Your priesthood is real and it is forever. You are a priest forever, and nothing will ever tarnish that in my sight.”

And the second light came a couple days later. I already was feeling honestly a peace and a joy in my prayer that I had not experienced in a very, very long time. And a couple days later, I was reading a book about Canadian missionaries, during the retreat, during some free time, about how they had gone out there and given their lives. And one person in this book reflects, “Isn’t it all a waste? Isn’t it all a waste when you’re out there and you’re just pouring yourself out and maybe no one is converted, and maybe no one listens to you? You’re fighting the elements and you’re fighting the hostility of the land, and the people, and nothing, no fruit comes from it.” And I thought to myself, again in prayer… I’d been so worried about fruitlessness, because I’ve always believed that God gives us talents and he expects a return on those talents. He expects a return on those gifts. And my priesthood was in a way the biggest of those gifts, the biggest of those talents, and that I was commissioned to go out and bear fruit that would last. And by renouncing my ministerial priesthood I feared that that fruit would be lost and that I would be letting God down and not producing what he wanted me to produce.

While I was praying about this, the Gospel passage came to my mind where Mary of Bethany anoints Jesus’ feet and she’s weeping over them and drying her tears with her hair. And she has this expensive aromatic nard and she breaks the vase that contains it and just pours it over Jesus’ feet. And the apostles are scandalized at the waste. “Why are you just throwing this all away?” The light that came to me was, “The love that you pour on your son Joshua I will take it as that aromatic nard, and no one can tell you that’s a waste. No one can tell you that your service is worth less than anything else you might have done. And I’ve got plans for you as well, things in store for you, but serving me is sufficient in itself, because that is a way of loving me which is authentic and it’s true.”

The article published in the magazine was an abridge version of the interview. Click here to read the entire interview.

Facebook Comments