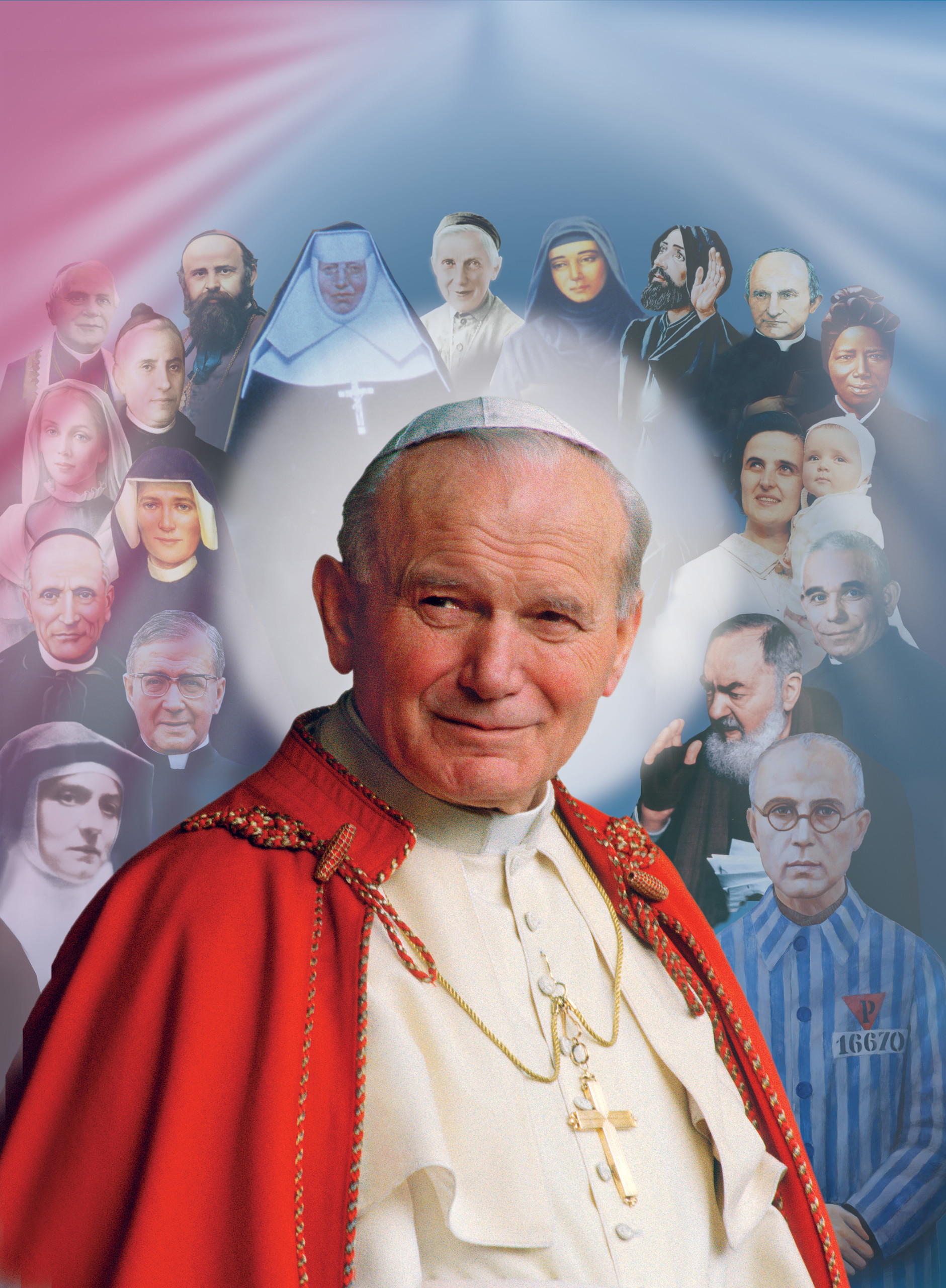

Some of the many saints canonized by Pope John Paul II. He was convinced that the Church needed models of sanctity. Now he himself will be one of those models and intercessors.

In the days before the canonizations of Blesseds John XXIII and John Paul II, Rome hotels were reporting they are almost fully booked and the Vatican has confirmed that the Mass will take place in St. Peter’s Square, despite the fact that hundreds of thousands of people will have to watch the ceremony on large video screens.

Pope Francis had announced in late September that he would proclaim the two Popes saints in a single ceremony April 27, Divine Mercy Sunday.

Less than two weeks after the date was announced, the Prefecture of the Papal Household issued an advisory that access to St. Peter’s Square would be first-come, first-served and warned pilgrims that unscrupulous tour operators already were trying to sell fake tickets to the Mass.

With perhaps more than 1 million people expected to try to attend the liturgy, rumors abounded that the Vatican would move the ceremony to a wide-open space on the outskirts of town. But the Vatican confirmed February 27 that the Mass would be held in St. Peter’s Square, just outside the basilica where the mortal remains of the two rest.

Blessed John Paul, known as a globetrotter who made 104 trips outside Italy, served as Pope from 1978 to 2005 and was beatified by Pope Benedict XVI on Divine Mercy Sunday, May 1, 2011. Blessed John XXIII, known particularly for convoking the Second Vatican Council, was Pope from 1958 to 1963; Pope John Paul beatified him in 2000.

In July last year, Pope Francis signed a decree recognizing the healing of a Costa Rican woman with a life-threatening brain aneurysm as the miracle needed for Blessed John Paul’s canonization. The same day, the Vatican announced that Pope Francis had agreed with members of the Congregation for Saints’ Causes that the canonization of Blessed John should go forward even without a second miracle attributed to his intercession.

A first miracle is needed for beatification. In Pope John Paul’s cause, the miracle involved a French nun suffering from Parkinson’s disease, the same disease the Pope had. In the cause of Pope John, the Vatican recognized as a miracle the healing of an Italian nun who was dying from complications after stomach surgery.

In February, Cardinal Angelo Amato, prefect of the Congregation for Saints’ Causes, said Pope Francis did not skip an essential step in approving Blessed John’s canonization, but “only shortened the time to give the entire Church the great opportunity of celebrating 2014 with John XXIII, the initiator of the Second Vatican Council, and John Paul II, who brought to life the pastoral, spiritual and doctrinal inspiration of its documents.”

The cardinal said Pope Francis did not dismiss the need for a miracle attributed to the late Pope’s intercession, but recognized that the “positio” or official position paper prepared for Blessed John’s cause, is “full of accounts of miracles” and favors granted by God through his intercession. One case, often mentioned, involves a woman from Naples who accidentally swallowed cyanide; she believes her poison-induced liver damage was miraculously reversed after prayers to Blessed John.

Asked by reporters in July to describe the two late Popes, Pope Francis said Blessed John was “a bit of the ‘country priest,’ a priest who loves each of the faithful and knows how to care for them; he did this as a bishop and as a nuncio” in Bulgaria, Turkey, Greece and France before becoming a cardinal and patriarch of Venice. He was holy, patient, had a good sense of humor and, especially by calling the Second Vatican Council, was a man of courage, Pope Francis said. “He was a man who let himself be guided by the Lord.”

As for Blessed John Paul, Pope Francis told the reporters on the plane, “I think of him as ‘the great missionary of the Church,” because he was “a man who proclaimed the Gospel everywhere.”

A spokeswoman for the office of Rome’s mayor said the city had plans for transporting pilgrims to and from the Vatican and providing them with water, toilet facilities and first aid stations.

Here and in the pages that follow, in honor of the two new saints, we reflect on some of the saints John Paul II canonized during his long pontificate. He firmly held that believers need strong models of Christian virtue and courage, and he chose these saints to be such models for all of us. Now, along with St. Pope John XXIII, he himself will be a model of virtue and holiness as St. Pope John Paul II.

Virginia Centurione Bracelli

Virginia Centurione Bracelli

April 2, 1587-December 15, 1651

S aint Virginia Centurione Bracelli was born on April 2, 1587, to a noble family in Genoa, Italy. She was the daughter of Giorgio Centurione, who was the Doge of Genoa from 1621 to 1623, and to Lelia Spinola.

Despite her desire to live a cloistered life, she was forced into marriage to Gaspare Grimaldi Bracelli, a wealthy noble, on December 10, 1602. She had two daughters, Lelia and Isabella. The marriage did not last long. She became a widow on June 13, 1607, at the age of 20. She refused another marriage arranged by her father and took a vow of chastity.

After her husband’s death she began charitable works and assisted the needy and sick. To help alleviate the poverty in her town, she founded the Centro Signore della Misericordia Protettrici dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo. The center was soon overrun with people suffering from the famine and plague of 1629-1630, and soon she had to rent the Monte Calvario convent to accommodate all the people. By 1635, the center was caring for over 300 patients and received recognition as a hospital from the government.

She spent the remainder of her life acting as a peacemaker between noble houses and continuing her work for the poor. She died on December 15, 1651, at the age of 64. Some years after her death, her body was found to be incorrupt.

Virginia was beatified on September 22, 1985, and canonized on May 18, 2003, by Pope John Paul II.

Maximilian Maria Kolbe

January 8, 1894-August 14, 1941

St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe, O.F.M. Conv., was a Polish Conventual Franciscan friar who volunteered to die in place of a stranger in the Nazi German death camp of Auschwitz, located in German-occupied Poland during World War II.

Due to Kolbe’s efforts to promote consecration and entrustment to Mary, he is known as the Apostle of Consecration to Mary.

He was born Raymund Kolbe on January 8, 1894 in Zduńska Wola, in the Kingdom of Poland, which was a part of the Russian Empire, the second son of Julius Kolbe and Maria Dabrowska. His father was an ethnic German and his mother was Polish. He had four brothers, Francis, Joseph, Walenty (who lived a year) and Andrew (who lived four years). Kolbe’s family moved to Pabianice, where his parents initially worked as basket weavers. In 1914, his father joined Józef Piłsudski’s Polish Legions and was captured by the Russians and hanged for fighting for the independence of a partitioned Poland.

Kolbe’s life was strongly influenced by a childhood vision of the Virgin Mary that he later described: “That night, I asked the Mother of God what was to become of me, a Child of Faith. Then she came to me holding two crowns, one white, the other red. She asked me if I was willing to accept either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity, and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both.”

In 1907, Kolbe and his elder brother Francis decided to join the Conventual Franciscans. They illegally crossed the border between Russia and Austria-Hungary and enrolled at the Conventual Franciscan minor seminary in Lwów. In 1910, Kolbe was allowed to enter the novitiate, where he was given the religious name Maximilian. He professed his first vows in 1911, and final vows in 1914, in Rome, adopting the additional name of Maria, to show his devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Kolbe would later sing hymns to the Virgin Mary in the concentration camp.

After the outbreak of World War II, which started with the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, Kolbe provided shelter to refugees from Greater Poland, including 2,000 Jews whom he hid from Nazi persecution in his friary in Niepokalanów. On February 17, 1941, he was arrested by the German Gestapo and imprisoned in the Pawiak prison. On May 28, he was transferred to Auschwitz as prisoner #16670. At the end of July 1941, three prisoners disappeared from the camp, prompting SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Fritzsch, the deputy camp commander, to pick 10 men to be starved to death in an underground bunker in order to deter further escape attempts. One of the selected men, Franciszek Gajowniczek, cried out, “My wife! My children!” Kolbe volunteered to take his place.

In his prison cell, Kolbe celebrated Mass each day and sang hymns with the prisoners. Each time the guards checked on him, he was standing or kneeling in the middle of the cell and looking calmly at those who entered. After two weeks of dehydration and starvation, only Kolbe remained alive. The guards wanted the bunker emptied and they gave Kolbe a lethal injection of carbolic acid. Some who were present at the injection say that he raised his left arm and calmly waited for the injection. His remains were cremated on August 15, the feast day of the Assumption of Mary.

Kolbe was canonized on October 10, 1982, by Pope John Paul II, and declared a martyr of charity. He is the patron saint of drug addicts, political prisoners, families, journalists, prisoners, and the pro-life movement. John Paul II declared him “The Patron Saint of Our Difficult Century.”

Katharine Drexel

Katharine Drexel

November 26, 1858-March 3, 1955

St. Katharine Drexel, S.B.S., was an American philanthropist, religious sister, educator, and foundress. She was canonized by Pope John Paul II on October 1, 2000. Her feast day is observed on March 3.

Katharine Drexel was born Catherine Marie Drexel in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the second child of investment banker Francis Anthony Drexel and Hannah Langstroth. Her family owned a considerable fortune, and her uncle Anthony Joseph Drexel was the founder of Drexel University in Philadelphia. Hannah died five weeks after her baby’s birth.

As a young and wealthy woman, Drexel made her social debut in 1879. However, watching her stepmother’s three-year struggle with terminal cancer taught her that the Drexel money could not buy safety from pain or death. Drexel’s life then took a profound turn.

When her family traveled to the Western states in 1884, Katharine Drexel saw the plight and destitution of the native Americans. She wanted to do something specific to help. Thus began her lifelong personal and financial support of numerous missions and missionaries in the United States.

After her father died in 1885, Katherine and her sisters had contributed money to help the St. Francis Mission on South Dakota’s Rosebud Reservation. For many years Kate took spiritual direction from a longtime family friend, Father James O’Connor, a Philadelphia priest who was later appointed apostolic vicar of Nebraska. When Katherine wrote him of her desire to join a contemplative order, Bishop O’Connor suggested, “Wait a while longer… Wait and pray.”

Katherine and her sisters were still mourning their father when they sailed to Europe in 1886. In January 1887, the sisters were received in a private audience by Pope Leo XIII. They asked him for missionaries to staff some of the Indian missions that they had been financing. To their surprise, the Pope suggested that Katherine become a missionary herself. Although she had already received marriage proposals, after consulting her spiritual director, Drexel decided to give herself to God, along with her inheritance, through service to American Indians and Afro-Americans. The Philadelphia Public Ledger carried a banner headline: “Miss Drexel Enters a Catholic Convent—Gives Up Seven Million.”

On February 12, 1891, Drexel professed her first vows as a religious, dedicating herself to work among the American Indians and Afro-Americans in the western and southwestern United States.

She took the name Mother Katharine, and joined by 13 other women, soon established a religious congregation, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament.

In 1910, Drexel financed the printing of 500 copies of A Navaho-English Catechism of Christian Doctrine for the Use of Navaho Children. About 100 Franciscan friars from St. John the Baptist Province started Our Lady of Guadalupe Province in 1985. Headquartered in Albuquerque, New Mexico, they continue to work on the Navajo reservation with the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. In all, Drexel established 50 missions for Native Americans in 16 states.

In 1935 Mother Katharine suffered a heart attack, and in 1937 she relinquished the office of superior general. She devoted her last years to Eucharistic adoration, and so fulfilled her lifelong desire for a contemplative life. Over the course of six decades, Mother Katharine spent about $20 million of her private fortune building schools and churches. She died at the age of 96, at her order’s motherhouse, where she is buried.

Her cause for beatification was introduced in 1966. Pope John Paul II canonized Mother Drexel on October 1, 2000, one of only a few American saints and the second American-born saint (Elizabeth Ann Seton was first natural-born US citizen canonized, in 1975). The Vatican cited fourfold aspects of Drexel’s legacy: (1) a love of the Eucharist and perspective on the unity of all peoples; (2) courage and initiative in addressing social inequality among minorities; (3) her belief in quality education for all and efforts to achieve it; and (4) selfless service, including the donation of her inheritance, for the victims of injustice.

Josephine Bakhita

Josephine Bakhita

c. 1869-February 8, 1947

Josephine Margaret Bakhita was a Sudanese-born former slave who became a Canossian religious sister in Italy, living and working there for 45 years. In 2000 she was declared a saint by the Roman Catholic Church.

She was born in about 1869 in the western Sudanese region of Darfur. She belonged to the prestigious Daju people. Her well-respected and reasonably prosperous father was a brother of the village chief. She was surrounded by a loving family of three brothers and three sisters; as she says in her autobiography: “I lived a very happy and carefree life, knowing nothing of suffering.”

Sometime between the ages of seven to nine, probably in February 1877, she was kidnapped by Arab slave traders, who had already kidnapped her elder sister two years earlier. She was cruelly forced to walk barefoot about 600 miles to El Obeid and had already been sold and bought twice before she arrived there. Over the course of 12 years (1877–1889), she was resold again three more times and then given away. It is said that the trauma of her abduction caused her to forget her own name; she took one given to her by the slavers, bakhita, Arabic for “lucky.” She was also forcibly converted to Islam.

In El Obeid, Bakhita was bought by a very rich Arab merchant who employed her as a maid in service to his two daughters. They liked her and treated her well. But after offending one of her owner’s sons, possibly for breaking a vase, the son lashed and kicked her so severely that she spent more than a month unable to move from her straw bed. Her fourth owner was a Turkish general and she had to serve his mother-in-law and his wife who both were very cruel to all their slaves. Bakhita says: “During all the years I stayed in that house, I do not recall a day that passed without some wound or other. When a wound from the whip began to heal, other blows would pour down on me.”

By the end of 1882, El Obeid came under the threat of an attack of Mahdist revolutionaries. The Turkish general began making preparations to return to his homeland. He sold most of his slaves but selected 10 of them to be sold later, on his way through Khartoum. There, in 1883, Bakhita was bought by the Italian Vice Consul Callisto Legnani, who was a very kind man. For the first time since her captivity she was able to enjoy some peace and tranquillity.

Two years later, when Legnani himself had to return to Italy, Bakhita begged to go with him. In April 1885, at the Italian port of Genoa, they were met by the wife of a friend, Augusto Michieli, who had escaped from Khartoum with them. Legnani gave Bakhita as a present to Signora Maria Turina Michieli, and her new masters took her to their family villa at Zianigo, near Mirano Veneto, about 16 miles west of Venice. She lived there for three years and became nanny to the Michieli’s daughter Alice, known as Mimmina, born in February 1886.

On January 9, 1890, Bakhita was baptized with the names of Josephine Margaret and Fortunata (which is the Latin translation for the Arabic Bakhita). On the same day she was also confirmed and received Holy Communion from Archbishop Giuseppe Sarto, the Cardinal Patriarch of Venice, the future Pope Pius X himself. On December 7, 1893 she entered the novitiate of the Canossian Sisters and on December 8, 1896, she took her vows, welcomed by Cardinal Sarto. In 1902, she was assigned to the Canossian convent at Schio, in the northern Italian province of Vicenza, where she spent the rest of her life.

A strong missionary drive animated her throughout her entire life — “her mind was always on God, and her heart in Africa.”

During her 42 years in Schio, her gentleness, calming voice, and ever-present smile became well known and Vicenzans still refer to her as Sor Moretta (“little brown sister”) or Madre Moretta (“black mother”). Her special charisma and reputation for sanctity were noticed by her order; the first publication of her story (Storia Meravigliosa by Ida Zanolini) in 1931, made her famous throughout Italy. During the Second World War (1939–1945) she shared the fears and hopes of the town people, who considered her a saint and felt protected by her mere presence. The bombs did not spare Schio, but the war passed without a single casualty.

Her last years were marked by pain and sickness. She used a wheelchair, but she retained her cheerfulness, and if asked how she was, she would always smile and answer “as the Master desires.” In the extremity of her last hours her mind was driven back to the years of her slavery and she cried out, “The chains are too tight; loosen them a little, please!” After a while she came round again. Someone asked her: “How are you? Today is Saturday.” “Yes, I am so happy: Our Lady… Our Lady!” These were her last audible words.

Bakhita died at 8:10 p.m. on February 8, 1947. For three days her body lay on display while thousands of people arrived to pay their respects.

A young student once asked Bakhita: “What would you do, if you were to meet your captors?” Without hesitation she responded: “If I were to meet those who kidnapped me, and even those who tortured me, I would kneel and kiss their hands. For, if these things had not happened, I would not have been a Christian and a religious today.”

The petitions for her canonization began immediately, and the process officially commenced by Pope John XXIII in 1959, only 12 years after her death. On December 1, 1978, Pope John Paul II declared Josephine “Venerable,” the first step toward canonization. On May 17, 1992, she was declared Blessed and given February 8 as her feast day. On October 1, 2000, she was canonized and became Saint Josephine Bakhita. She is venerated as a modern African saint, and as a statement against the brutal history of slavery. She has been adopted as the only patron saint of Sudan.

Bakhita’s legacy is that transformation is possible through suffering. Her story of deliverance from physical slavery also symbolizes all those who find meaning and inspiration in her life for their own deliverance from spiritual slavery.

Pope Benedict XVI, on November 30, 2007, in the beginning of his second encyclical letter Spe Salvi (“In Hope We Were Saved”), relates her entire life story as an outstanding example of Christian hope.

Gianna Beretta Molla

Gianna Beretta Molla

October 4, 1922-April 28, 1962

St. Gianna Beretta Molla, an Italian pediatrician, wife and mother, is best known for refusing an abortion when she was pregnant with her fourth child, despite knowing that continuing with the pregnancy could result in her death. She was canonized as a saint of the Catholic Church in 2004.

Gianna Beretta was born in Magenta, Italy, the 10th of 13 children in her family, only nine of whom survived to adulthood. When she was three, her family moved to Bergamo, and she grew up in the Lombardy region of Italy.

In 1942, Gianna began her study of medicine in Milan. Outside of her schooling, she was active in Catholic Action. She received a medical diploma in 1949, and opened an office in Mesero, near her hometown of Magenta, where she specialized in pediatrics.

Gianna hoped to join her brother, a missionary priest in Brazil, where she intended to offer her medical expertise in gynecology to poor women. However, her chronic ill health made this impractical, and she continued her practice in Italy.

In December 1954, Gianna met Pietro Molla, an engineer 10 years older than she. They were officially engaged the following April, and they married in September 1955. They welcomed Pierluigi in 1956, Mariolina in 1957, and Laura in 1959.

In 1961, Gianna was pregnant once again. During the second month, she developed a fibroma on her uterus. After examination, the doctors gave her three choices: an abortion, a complete hysterectomy, or removal of only the fibroma. Gianna opted for the removal of the fibroma, wanting to preserve her child’s life.

After the operation, complications continued throughout her pregnancy. Gianna was quite clear about her wishes, expressing to her family, “This time it will be a difficult delivery, and they may have to save one or the other — I want them to save my baby.”

On April 21, 1962, Good Friday of that year, Gianna went to the hospital, where her fourth child, Gianna Emanuela, was successfully delivered via Caesarean section. However, Gianna continued to have severe pain, and died of septic peritonitis 7 days after the birth.

Gianna was beatified by Pope John Paul II on April 24, 1994, and canonized on May 16, 2004. Gianna’s husband Pietro, and three of their children, including Gianna Emanuela, were present at the canonization ceremony, the first time in the history of the Church that a husband witnessed his wife’s canonization.

In his homily at her canonization Mass, Pope John Paul II called Gianna “a simple, but more than ever, significant messenger of divine love.”

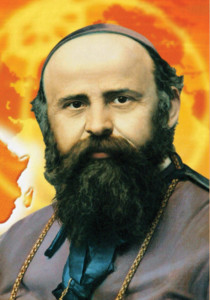

Daniel Comboni

Daniel Comboni

March 15, 1831-October 10, 1881

Daniel Comboni was a Roman Catholic missionary to Africa and saint. He was born in Brescia, Italy. Comboni lived in poverty during his youth and so went to school in Verona, at an institute founded by Father Nicola Mazza. During the years spent in Verona, Daniel discerned his calling to the Catholic priesthood, and completed his studies. During this time, Comboni was entranced by the mission to Central Africa after hearing descriptions from the missionaries who returned from there. On December 31, 1854, the year of the proclamation of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, Daniel was ordained a priest by the bishop of Trent, Blessed John Tschiderer. Three years later, with the blessing of his mother, he left for Africa along with five other missionaries of the Mazza Institute.

After four months, Comboni reached Khartoum, capital of the Sudan. The impact of this first face-to-face encounter with Africa was tremendous, Daniel was immediately made aware of the

multiple difficulties that were part of his new mission. But labors, unbearable climate, sickness, the deaths of several of his young

fellow-missionaries, the poverty of the population, only served to drive him forward, never dreaming of giving up what he had taken on with such great enthusiasm. From the mission of Holy Cross he wrote to his parents: “We will have to labor hard, to sweat, to die: but the thought that one sweats and dies for love of Jesus Christ and the salvation of the most abandoned souls in the world, is far too sweet for us to desist from this great enterprise.”

After witnessing the death of one of his missionary companions, Daniel, far from being discouraged, felt an interior confirmation of his decision to carry on in the mission, as he wrote: “O Nigrizia o morte!”— “Either Africa, or death.”

Ever confident in his mission, Comboni worked out a fresh missionary strategy in 1864 in Italy. While praying at the Tomb of St. Peter in Rome, Daniel was struck by an inspiration that led to the drawing up of his “Plan for the Rebirth of Africa,” a missionary project that can be summed up in an expression which is itself the indication of his boundless trust in the human and religious capacities of the African peoples: “Save Africa through Africa.”

In spite of all the problems and misunderstandings faced, Daniel strove to drive home his intuition: that European society and the Church were called to become much more concerned with the mission of Central Africa. He undertook a tireless round of missionary appeals throughout Europe, begging for spiritual and material aid for the African missions from royalty, bishops and nobles, as well as from the lay peoples. Around this time he also launched a missionary magazine, the first in Italy.

Comboni established a men’s missionary institute in 1867 and one for women in 1872: the “Comboni Missionaries” and the “Comboni Missionary Sisters.” He was the first to bring women into missionary work in Central Africa.

Comboni took part in the First Vatican Council as the theologian of the Bishop of Verona, and was able to get 70 bishops to sign a petition for the evangelization of Central Africa: Postulatum pro Nigris Africæ Centralis. The Postulatum was not discussed due to the Council’s premature end.

On July 2, 1877, Daniel was named apostolic vicar of Central Africa, and ordained bishop in August 1877: a confirmation that his ideas, considered by some to be foolhardy, were recognized as a truly effective means for the proclamation of the Gospel.

In 1880, Bishop Comboni traveled to Africa for the eighth and final time, to stand alongside his missionaries: intent, also, on continuing the struggle against the slave trade, and on consolidating the missionary activity carried out by Africans themselves. Just one year later on October 10, 1881, after falling gravely ill from disease, he died in Khartoum. His final words were reported to be: “I am dying, but my work will not die.”

He was canonized by Pope John Paul II on October 5, 2003, in Rome.

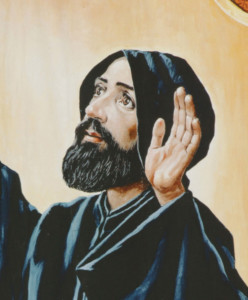

Nimatullah Kassab Al-Hardini

Nimatullah Kassab Al-Hardini

1808-December 14, 1858

St. Nimatullah Kassab, O.L.M., was a Lebanese monk, priest and scholar of the Maronite Church. He was born Youssef Kassab, in 1808 in the village of Hardine, in the North Governorate of Lebanon, one of the seven children of George Kassab and Marium Raad, the daughter of a priest of the Maronite Church.

As a boy, Youssef attended the school run by the monks of the Lebanese Maronite Order at the Monastery of St. Anthony in the village of Houb. After he finished his studies there in 1822, he entered the Monastery of St. Anthony in Qozhaya, at which time he took the monastic name of Nimatullah, by which he is now known. As a new monk, Father (the title given to all Eastern monks) Nimatullah was assigned by the abbot of the monastery to learn how to bind books. Yet he spent the period of his initial formation in the monastic life in frequent prayer, sometimes passing the night in prayer in the monastery church, praying to the Blessed Sacrament.

Kassab made his religious profession of vows on November 14, 1830, after which he was sent to the Monastery of Saints Cyprian and Justina to pursue higher studies in preparation for ordination, which took place on Christmas Day 1833.

After ordination, he was assigned by the abbot to teach at the Order’s seminary and to be the director of the seminarians. Among his students was a famed member of the Order, St. Sharbel Makhluf, venerated by the entire Catholic Church.

As a monk, Kassab spent his entire life in prayer and the service of his Order. He was severe on himself but a model of patience and forbearance to his fellow monks, to the point where he was reprimanded for his leniency. He bore all this as part of the challenge of monastic life. One of his brothers, who had also entered the monastery and had become a hermit, advised him to seek a similar solitude. Nimatullah declined, saying that community life was the true challenge for a monk.

Kassab fell ill in the winter of 1858, dying on December 14 after suffering nearly two weeks of high fever. In 1864, his tomb was opened for re-burial and, to the surprise of the monks, his body was found to be intact. Such was the reverence with which he was held during his life, that his body was exposed to the veneration of the public until 1927, when a committee of inquiry into his possible canonization had completed its work. His body was then reburied in a small chapel.

Kassab is believed to have performed many miracles during his life due to his deep spirituality and his high virtues. According to some sources, on one occasion when he was teaching his students and facing a large wall outside the monastery of Kfifan, he had a sense that the wall was suddenly going to fall. Thereupon, he asked his students to move away just before the wall fell down, sparing all present from injury.

Another miracle apparently occurred to a Melkite man, Mickael Kfoury, from the town Watta El-Mrouge. An incurable illness was attacking both of his legs, which rendered them dry, devoid of flesh, and twisted to the point of crippling him. His doctors had abandoned all hope of a cure.

Having heard of the miracles that Father Nimatullah was performing, this man decided to visit Father Nimatullah’s tomb in Kfifan and ask for his healing. He slept the night at the monastery, and while he was in deep sleep an old monk appeared to him saying: “Stand up and go and help the monks carry in the grapes from the vineyard.” He immediately replied: “Don’t you see me paralyzed? How can I walk and carry the grapes?” The monk answered: “Take this pair of shoes, wear them and walk.” The sick man then took the shoes and tried to stretch out his right leg, and, to his surprise, he was able to do so. He woke up and started to feel both of his legs which were now full of blood and flesh, and after he stood up he found himself totally healed.

The cause for Kassab’s canonization was formally accepted by the Holy See on September 7, 1978, and he was declared Venerable. Kassab’s beatification by Pope John Paul II was held at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome on Sunday, May 10, 1998. He was canonized on Sunday, May 16, 2004, by the same Pope. The Maronite Church celebrates his feast day on December 14.

Edith Stein

Edith Stein

October 12, 1891-August 9, 1942

Edith Stein, also known as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, OCD (German: Teresia Benedicta vom Kreuz, Latin: Teresia Benedicta a Cruce), was a German Jewish philosopher who converted to the Roman Catholic Church and became a Discalced Carmelite nun. She is a martyr and saint of the Catholic Church.

She was born into an observant Jewish family, but was an atheist by her teenage years. Moved by the tragedies of World War I, in 1915 she took lessons to become a nursing assistant and worked in a hospital for the prevention of disease outbreaks. After completing her doctoral thesis in 1918 from the University of Göttingen, she obtained a teaching position at the University of Freiburg.

From reading the works of the reformer of the Carmelite Order, St. Teresa of Jesus, OCD, she was drawn to the Catholic Faith. She was baptized on January 1, 1922, into the Roman Catholic Church. At that point she wanted to become a Discalced Carmelite nun, but was dissuaded by her spiritual mentors. She then taught at a Catholic school of education in Münster.

As a result of the requirement of an “Aryan certificate” for civil servants promulgated by the Nazi government in April 1933 as part of its Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, she had to quit her teaching position. She was admitted to the Discalced Carmelite monastery in Cologne the following October.

She received the religious habit of the Order as a novice in April 1934, taking the religious name Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (“Teresa blessed by the Cross”).

In 1938, she and her sister Rosa, by then also a convert and an extern Sister of the monastery, were sent to the Carmelite monastery in Echt, Netherlands for their safety. Despite the Nazi invasion of that state in 1940, they remained undisturbed until they were arrested by the Nazis on August 2, 1942 and sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp, where they died in the gas chamber on August 9, 1942.

She was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1998. She is one of the six patron saints of Europe, together with St. Benedict of Nursia, Sts. Cyril and Methodius, St. Bridget of Sweden, and St. Catherine of Siena. In her testament of June 6, 1939, the saint wrote: “I beg the Lord to take my life and my death… for all concerns of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary and the Holy Church, especially for the preservation of our Holy Order, in particular the Carmelite monasteries of Cologne and Echt, as atonement for the unbelief of the Jewish People, and that the Lord will be received by His own people and His kingdom shall come in glory, for the salvation of Germany and the peace of the world, and lastly for my loved ones, living or dead, and for all God gave to me: that none of them shall go astray.”

Maria Faustina Kowalska

Maria Faustina Kowalska

August 25, 1905-October 5, 1938

Maria Faustyna Kowalska, commonly known as St. Faustina (born Helena Kowalska, in Kraków, Poland), was a Polish nun, mystic and visionary who is known and venerated as the Apostle of Divine Mercy.

Throughout her life, Faustina reported having visions of Jesus and conversations with him, which she wrote about in her diary, later published as the book The Diary of Saint Maria Faustina Kowalska: Divine Mercy in My Soul.

At age 20 she joined a convent in Warsaw and was later transferred to Płock and then to Vilnius where she met her confessor, Father Michael Sopocko, who supported her devotion to the Divine Mercy.

Faustina wrote that on the night of Sunday, February 22, 1931, while she was in her cell in Płock, Jesus appeared to her as the “King of Divine Mercy” wearing a white garment with red and pale rays emanating from his heart. In her diary (Notebook I, items 47 and 48) she wrote that Jesus told her: “Paint an image according to the pattern you see, with the signature: ‘Jesus, I trust in You.’ I desire that this image be venerated, first in your chapel, and then throughout the world. I promise that the soul that will venerate this image will not perish.”

Not knowing how to paint, Faustina approached some other nuns at the convent in Płock for help, but received no assistance.

Three years later, after her assignment to Vilnius, the first artistic rendering of the image was painted under her direction.

In the same February 22, 1931 message about the Divine Mercy image, Faustina also wrote in her diary (Notebook I, item 49) that Jesus told her that he wanted the Divine Mercy image to be “solemnly blessed on the first Sunday after Easter; that Sunday is to be the Feast of Mercy.”

Faustina was canonized by Pope John Paul II on April 30, 2000.

A woman is holding up Maria Faustina Kowalska’s portrait before the canonization ceremony.

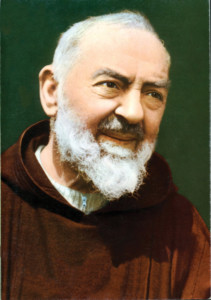

Pio da Pietrelcina

Pio da Pietrelcina May 25

1887-September 23, 1968

St. Padre Pio (Pius) of Pietrelcina, O.F.M. Cap., was a Capuchin priest from Italy now regarded as one of the greatest saints of the 20th century. He is famous for his mystical battles with the devil, and for having borne the marks of the wounds of Christ, the stigmata, in his body.

He was born Francesco Forgione, and given the name Pius (Italian: Pio) when he joined the Capuchins; thus he is popularly known as Padre Pio.

On January 6, 1903, at the age of 15, he entered the novitiate of the Capuchin Friars at Morcone where, on January 22, he took the Franciscan habit and the name of Fra (Friar) Pio, in honor of Pope St. Pius V, the patron saint of Pietrelcina. He took the simple vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. Three years later, on January 27, 1907, he made his solemn profession.

At 17, he suddenly fell ill, complaining of loss of appetite, insomnia, exhaustion, fainting spells, and terrible migraines. He vomited frequently and could absorb only milk and cheese. It was during this time, together with his physical illness, that inexplicable phenomena began to occur. One could hear strange noises coming from his room at night — sometimes screams or roars. One of Pio’s fellow friars claims to have seen him in ecstasy, levitating above the ground. Based on his correspondence, even early in his priesthood he experienced indications of the visible stigmata for which he would later become famous. In a 1911 letter, he wrote to his spiritual advisor, Padre Benedetto from San Marco in Lamis, describing something he had been experiencing for a year: “Then last night something happened which I can neither explain nor understand. In the middle of the palms of my hands a red mark appeared, about the size of a penny, accompanied by acute pain in the middle of the red marks. The pain was more pronounced in the middle of the left hand, so much so that I can still feel it. Also under my feet I can feel some pain.” His close friend Padre Agostino wrote to him in 1915, asking specific questions such as when he first experienced visions, whether he had been granted the stigmata, and whether he felt the pains of the Passion of Christ, namely the crowning of thorns and the scourging. Padre Pio replied that he had been favored with visions since his novitiate period (1903 to 1904). He wrote that although he had been granted the stigmata, he had been so terrified by the phenomenon he begged the Lord to withdraw them. He did not wish the pain to be removed, only the visible wounds, since at the time he considered them to be an indescribable and almost unbearable humiliation.

On June 16, 2002, Padre Pio was canonized by Pope John Paul II.

Facebook Comments