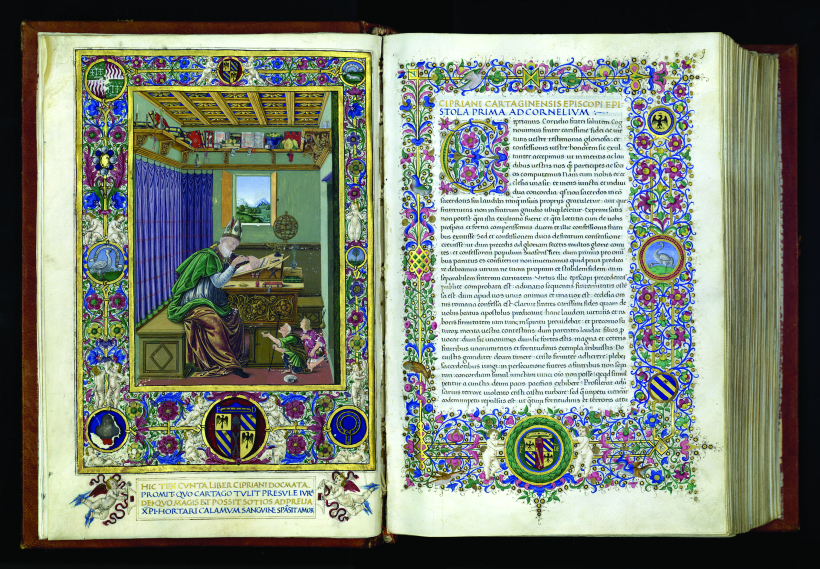

Benozzo Gozzoli, “The Triumph of St. Thomas Aquinas over Averroes, the Most Influential Muslim Philosopher of the Middle Ages, with Aristotle and Plato,” The Louvre in Paris, from 1471

Human beings are a composite of mortal body and immortal soul. At the moment of death, that composite is torn asunder… and yet we remain ourselves. Part two of a reflection on human nature by the great Belgian philosopher Dr. Alice von Hildebrand

Let us now turn to an historic fact that had an enormous impact on the philosophical and theological situation of the West: the Islamic invasion of the West from the 600s on, which brought about a philosophical turmoil. For the Muslims were cognizant of Aristotle’s metaphysical works, unknown in the West. These works were soon translated into Latin and, as could have been predicted, not only challenged the prevalent philosophy strongly marked by St. Augustine’s Platonic leanings, but moreover — and this was a major concern — challenged some key Biblical claims such as the eternity of the world.

Genesis made it clear that, by divine revelation, the world was created (not produced) in time, and is therefore not eternal.

“The Philosopher,” as St. Thomas Aquinas called Aristotle, who was inevitably ignorant of Biblical teaching and based his views on reason alone, came to the conclusion that what we call “the world” was eternally “produced” by a “prime mover” or primary cause which is itself necessarily unmoved and uncaused. What it has “produced” will, like its cause, eternally continue to exist.

Moreover, it is Aritotle’s claim that this prime mover is unaware of the existence and nature of what it produced, for the plain reason that knowing things that are “produced” and therefore imperfect, would detract from its perfections. (This was wittily remarked upon by a mediaeval thinker, telling us that he was “feeling sorry” for Aristotle’s God, who was denied a knowledge that he, an imperfect creature, possessed.) Can an ignorant God be a true God?

Religion, so prominent in Plato, is necessarily eliminated in Aristotle, and this has grave consequences, particularly in his ethics, which is inevitably bound to be man-centered, and must logically claim that the ultimate purpose of his existence is to attain happiness. But, is a man who failed to reach happiness immoral? Is he stupid? Should we assume that the most intelligent among us will be the happiest?

Aristotle’s thought clearly challenges some basic tenets of Christianity (unbeknownst to him) and this has grave consequences for a Christian philosopher and theologian who, while wisely acknowledging the merits and genius of the pagan Aristotle, must convince his readers that Aristotle’s views undermine Biblical teaching.

The “tool” used by The Philosopher was reason; the Bible did not reason, did not prove: its teaching is accepted on faith, that is, on one’s intellectual knees. The duel between faith and reason had begun.

The crucial question was: If Aristotle can “refute” the Bible, would the very foundation of Christianity inevitably collapse? The faith needed an intellectual champion. This mission was confided to Thomas Aquinas.

One thing should be clear from the start, and that is Aquinas’ profound admiration for “The Philosopher,” whom he definitely placed above Aristotle’s teacher, Plato.

But Thomas was not only a deeply believing Christian: he was on his way to holiness. And what he achieved calls for grateful admiration, but it would be a great mistake to assume that to baptize this pagan genius did not involve some serious difficulties. For Aristotle, body and soul are closely knit, but how is one to guarantee the immortality of the soul? This is a question that I leave to Aristotelian scholars to deal with.

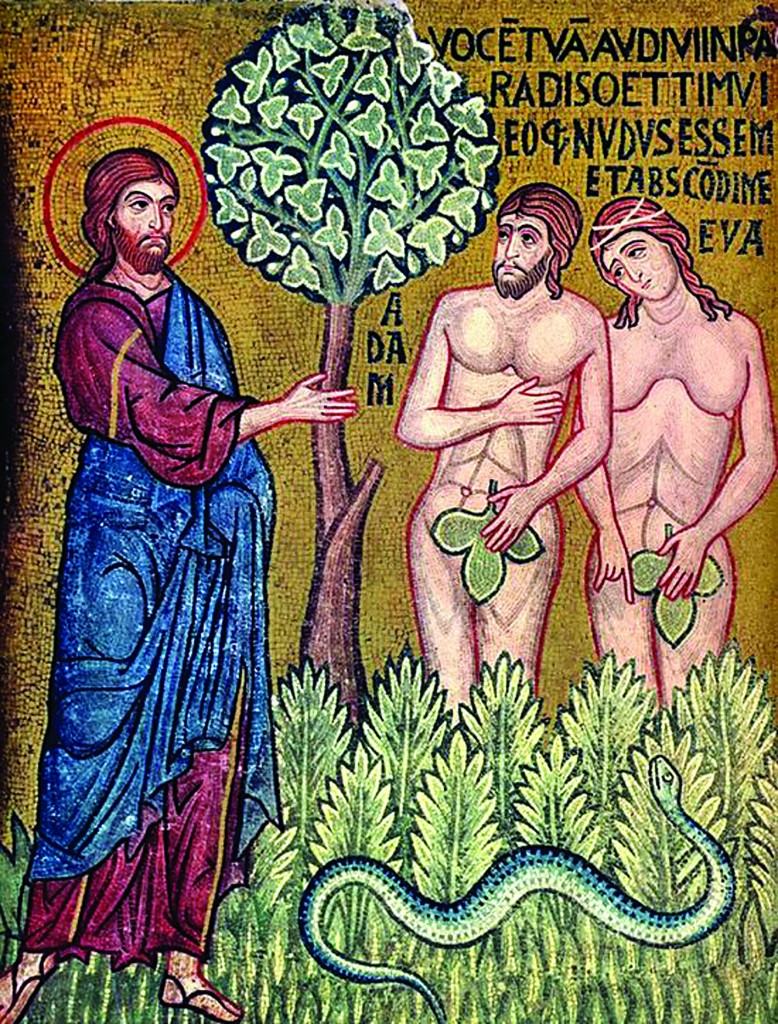

Genesis tells us clearly that man is made up of a material body (in the case of Adam, it is specified that it was made from the slime of the earth, in the case of Eve, from Adams’s body) and then that God breathed into his nostrils the breath of life and gave him a soul. But — unbeknownst to Aristotle of course, — the evil serpent induced Eve to eat of a forbidden fruit; she was lured by his promise that by so doing she and her husband would become equal to God. Eritis sicut Dei. The well-deserved punishment for this disobedience was death, but this death affected only the human body, not the human soul marked by immortality.

Before original sin, the body benefited from the immortality of the soul: it was not marked for death. Its being now condemned to death is one of the most severe punishments of its proud disobedience: death is in fact a “tearing apart” of body and soul and is inevitably linked to anguish and suffering. That the guilty soul is not condemned to death might make us raise the question: is not this fearful tearing apart of body and soul a “dualistic” punishment that God has inflicted upon His guilty creatures?

“Adam and Eve Cast Out of the Terrestrial Paradise” (Duomo di Monreale)

But the punishment that afflicted our first parents (and alas all of us by inheritance) is still more tragic and more complex — namely: up to original sin, there was harmony not only between man and his Creator, but also between body and soul. Sin gravely disrupted this harmony in which the latter was the “conductor,” while the former obeyed. But now, the body, poisoned by concupiscence, started clamoring for the immediate satisfaction of whatever urge arose in it; the door was now wide open for sins such as lust, gluttony and sloth. (Let us think of the tragic character of Oblomov in Goncharof’s powerful novel.)

Alas, it also disrupted the harmony that existed between our first parents: from then on, there was a tacit state of war between them, shedding light on the very dark chapter of men’s brutality and selfishness toward the physically weaker sex (I say “physically,” because according to Confucius there is nothing as strong as a woman: women have an enormous influence and therefore power over men.)

Man now finds himself in a battlefield on several fronts, and must acknowledge defeat on all three: he desperately needs a Savior.

In this context, I shall limit myself to discussing the relationship between body and soul. That the body, affected and infected by concupiscence, can make life difficult for the soul is too well known to call for details. The seven capital sins make it clear that both body and soul are vulnerable.

It should now be clear that if one believes that man is a pure spirit, i.e., angelic (an accusation leveled at Descartes because his “Cogito, ergo sum” seemingly denied the metaphysical role played by man’s body), this view must be thrown out of court: Genesis makes it luminously clear that man is made of both body and soul.

But whereas according to God’s plan, before original sin, man’s body was a beneficiary of the soul’s immortality, a consequence of this grave revolt was that it was condemned to “return to dust.”

This is one great mystery. In the meantime, is it not legitimate to speak of a de facto dualism? The body in a casket? The existence of the soul unaffected by the death of its life-long companion? The bodies of the dead are “no more” and yet are promised resurrection.

One is tempted to say that resurrection is, then, very close to “re-creation”: we believe that it is our own body that will be given back to us, but it will be a spiritualized body characterized by impassibility, clarity, agility and subtlety.

Their union will then be so perfect that the moral “dualism” — the lack of harmony that we have referred to, i.e. the tension, the battle, existing between them on this earth — will be replaced by a glorious peace.

The perfect unity of body and soul as originally intended by God will be fully reestablished.

In other words, can we suggest that whereas metaphysical dualism is a grave error, and justly condemned, “an existential dualism” is a true and sad consequence of original sin?

To summarize: To deny that the human person is composed of both body and soul cannot in any way be justified. Genesis is explicit on the subject, and backed up by indubitable fact.

But that this relationship is both mysterious and complex can also not be denied. I argue that the tension between a spiritual soul and a material body is a punishment of original sin. For at the moment of creation, not only were they superbly matched, but experienced as a gift.

As a punishment of man’s revolt against God, the body revolted against the soul. Sins such as lust, gluttony, and sloth were inevitably manifestations of this “non serviam.” The closeness of the union of body and soul, instead of being a duo, sang “off-tune” and often resulted in a cacophony, or rather, a funeral march.

Then came the fearful punishment of death: soul and body so closely united were torn apart, with the pain and anguish linked to it. But whereas the body rotted and disintegrated, the soul enjoyed immortality, either in heaven, or in purgatory, or, alas, freely-chosen hell. That the soul can enjoy the beatific vision without the body is a tremendous mystery. But this is not the end: according to divine dogma, the mortal bodies will be brought back to life and reunited to their souls, now transfigured and spiritualized.

Dr. Alice von Hildebrand

It is a mystery. Woe to the philosophers who in their pride reduce mysteries to problems. Indeed, “there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy”: this is why the greatest philosophers are men of faith.

Alice von Hildebrand is a Catholic philosopher renowned for her brilliant mind and her profound Catholic faith. She is the widow of the late Dr. Dietrich von Hildebrand.

Facebook Comments