Pope Benedict XVI and Msgr. Alfred Xuereb during the prayer of the Angelus at Castel Gandolfo, summer papal residence, near Rome, on July 10, 2011 (Galazka photo).

“To contrast Popes with each other reduces them because one loses the beautiful aspects and the significant characteristics of their personalities.”

Monsignor Alfred Xuereb speaks from personal experience. For almost six years he served as one of Pope Benedict XVI’s personal secretaries, and since March of 2013 he has been at the service of Pope Francis. He is known for his discretion and diligence. It was precisely Pope Benedict who offered the Maltese monsignor to his successor as a possible secretary.

“I was with Benedict XVI [at Castel Gandolfo outside of Rome] until three days after the election [on March 13] of Pope Francis,” Msgr. Alfred recalls. “After that, I came back to the Vatican, to Domus Sanctae Marthae. The day I left I recall minute by minute, because it was a very special moment for me. For almost six years I had been beside a very special person, who loved me as a father loves a son, who allowed me to enjoy a respectful but intimate confidence. Then came the day of our painful separation.”

Msgr. Alfred has long experience in the service of Roman pontiffs. He was a Prelate of the Antechamber during the last years of the pontificate of John Paul II, then was one of the personal secretaries of Benedict XVI, and now is at the side of Pope Francis.

His almost British discretion has prevented him from becoming known to the general public, but in the Vatican his smile and friendliness are well known and appreciated.

“In harmony with the style of Pope Francis and in order to work quickly through the huge stack of letters and documents that are sent to the personal secretary, just like in any other office, I spend a lot of my time at my desk,” Msgr. Alfred says.

Msgr. Georg Gaenswein and Msgr. Alfred Xuereb during the Mass celebrated by Pope Benedict XVI at the International Stadium in Amman, Jordan,

on May 10, 2009 (Galazka photo).

Pope Francis, in a gesture of profound trust and appreciation, recently named him to watch over and keep him informed, to be his “eyes and ears,” as it were, regarding the work of the Oversight Commission of the Istituto per le Opere di Religione (the IOR, sometimes referred to as the “Vatican bank”) and over the Commission for Study and Planning on the Organization of the Economic-Administrative Structures of the Holy See.

Born in Victoria, Malta, in 1958, Msgr. Alfred, now 56, has been a priest for 30 years, since 1984, when he was ordained at the age of 26. He studied first in Gozo, in Malta, and then at the Institute of Spirituality of the Teresianum in Rome. He passed one year working in Muenster in Germany, then was, from 1991 to 1995, secretary of the Rector of the Lateran University in Rome. From there he went to the Vatican’s Secretariat of State, and then to his long service in the Pontifical Household.

Looking back at a distance of a few months from the events of early 2013 that changed history, Msgr. Alfred told us how he lived through that period, but above all opens the memory-book of his mind to recount Benedict XVI as he saw him, up close and personal. The account of those days in March is intense and rich.

You became the secretary of Pope Francis after being the secretary of Pope Benedict. How did that happen?

Monsignor Alfred Xuereb: Benedict XVI had written a very beautiful letter, a copy of which he gave to me, which I keep as a precious jewel, in which he mentioned to the new Pope some of my qualities. Perhaps in his goodness he wanted to avoid listing my defects. He assured the new Pope that he had left me free, as the new Pope was unwilling to ask me to leave my service to Pope Benedict. However, the new Pope was perhaps the only one among the 115 cardinals who did not have his own personal secretary. I remember even the moment that I packed my bags. They were saying to me, ‘Hurry, the new Pope needs a secretary, he is opening his own letters, he is alone.’ I did not know anything about what was happening in the Domus Sanctae Marthae.”

A white baseball cap is thrown toward Pope Francis as he leaves in a jeep after visiting San Gerlando Parish in Lampedusa, Italy, July 8, 2013.

How did you say farewell to Pope Benedict?

Xuereb: The most touching moment was when I entered his office at Castel Gandalfo to say goodbye to him personally. Then there was the last common lunch, but that private moment was very moving. I wept, and I said to him, with difficulty, as I had a great lump in my throat that made it difficult for me to speak, “Holy Father, for me it is very difficult to leave you. I thank you deeply for what you have given me in these years, for treating me like a son.” He stood up from his desk and, as I kissed the ring on his finger that was already no longer the ring of the Fisherman, he placed his right hand on my head and blessed me.

Do you have other vivid memories of the time when you were serving Pope Benedict?

Xuereb: Once, we were at Castel Gandolfo. There was an encounter with seminarians and priests. One of the priests had observed how difficult it is to observe all the hours of prayer because his parish was large and there were many people he needed to care for. And he said, almost asking for forgiveness, that he did not always manage to pray his breviary, because he had to help one or another of his parishioners. Perhaps he was awaiting almost a word of approval.

But Pope Benedict said to him: “Your pastoral commitment is very praiseworthy, but recall that also when you are praying the breviary you are carrying out pastoral work because you are praying for your parishioners. As it is important to help a person by listening to him and by doing concrete things to help him, it is just as important to help him and support him with your prayer. Parishioners appreciate this very much when they come to know of it.”

And so the Pope encouraged the parish priest to not undervalue the Liturgy of the Hours.

You were part of Pope Benedict’s “family.” You experienced Benedict’s kindness. In requests for prayer, for example…

Xuereb: Every day many letters for Pope Benedict arrived with requests for prayers. The same thing happened with John Paul II and it was the task of Fr. Mietek, which I inherited, to prepare the prayer requests on a little sheet of paper for the Pope.

Many requests came from sick people and the Pope was struck by how many families lived through tragedies, thinking not only of the sick people themselves, but also of their entire families who, night and day, at Christmas and at Easter, in summer and in winter, had to care for the sick family member.

And then there was concern for the children. The Pope, despite his myriad concerns, considered his prayer for the sick an extremely important pastoral ministry. Fr. Mietek placed the little pieces of paper in his chapel on his kneeler, and I know that Pope Benedict read them and re-read them, keeping them in his little desk. He surprised me when, after some days, he asked me if I had some news of one of the sick whom I knew personally.

Benedict XVI’s zucchetto.

Do you recall anything about his prayer life?

Xuereb: His time of contemplation before Mass. Mass began at 7 a.m., but there were days in which we heard the clock in the Cortile San Damaso sound the hour but he remained in contemplation. I recall one period in particular, in which he kept still for a long time even after the hour to begin had sounded. I had the clear sensation that he was praying for a particular intention. Perhaps it was a moment of interior struggle that he had had before arriving at the heroic decision to renounce the papacy. It was a very particular time of quiet reflection.

In the Pope’s daily life there were also some special festive moments like Christmas. Do you recall your first Christmas with Pope Benedict?

Xuereb: We were around the Christmas tree with the candles lit as is the custom in Germany. We sang Christmas carols in German, in Latin, and in Italian. At a certain moment the Pope turned toward me and said: “Your predecessor, Fr. Mietek, sang a few songs for us in Polish. Are you able to sing any in Maltese?”

I had a few of our popular songbooks, including one with the music and words for the most traditional song of all: Ninni la Tibkix Izjed, that is, “Hush, hush little Jesus, do not cry any more.” It is sung every Christmas. I ran to my office and picked up the songbooks and my surprise and emotion were great when the Pope took the songbook and sat down at the piano to play it. Hearing that melody played by the Pope… still today the thought moves me deeply…

On Christmas Eve, after dinner, as we waited for Mass to begin, we gathered around the lit tree, and the Pope opened the missal to the passage of the Gospel recounting the birth of Jesus and read it; then we exchanged Christmas greetings. He explained to me that every father of a family in Bavaria does the same thing. I appreciated enriching the great popular religious piety of the Maltese which I had known with that of Bavaria.

During and after meals, or after a walk in the Vatican Gardens for the recitation of the Rosary, you spoke with Pope Benedict about the audiences of the day, even about the criticisms that arrived from outside and from inside the Church. Were there difficult times?

Xuereb: I sometimes saw him displeased, certainly, but never cast down. I never once heard him speak a phrase of disdain. When there was the sad affair of his butler, whom he treated like a son, he manifested his sadness for the butler’s family and for the butler himself. But never an indignant word.

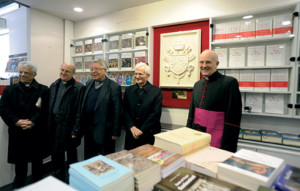

Papal Secretary Msgr Alfred Xuereb and Msgr. Joseph Farrugia on the occasion of Pope Francis’ Donation to the Maltese Museum in Gozo.

Msgr. Alfred, were you with Pope Benedict when Pope Francis, just after his election, called him on the telephone?

Xuereb: Benedict followed the news of the Conclave with great attention; he was anxious to know who would succeed him. We prayed intensely, feeling ourselves united to the entire Church which was invoking the Holy Spirit. The moment of the “annuntio vobis gaudium magnum” we followed on television. It was very moving to be present at the moment of the telephone call that the new Pope made to Pope Benedict. I passed him the cordless phone, and I heard Benedict say: “Thank you, Holy Father” — and already to hear Benedict speak those words was astonishing to me — “thank you for having thought of me immediately and I promise you from this instant forward my obedience and my prayers.” These words, spoken by a person with whom I had lived, because he was my Pope, to hear him say this, well, I remained deeply edified.

How did you experience the decision to renounce the papacy?

Xuereb: My fear was that he would be misunderstood and perhaps even generally condemned. I feared that people might say: “He began his task and did not have the courage to complete it!” But instead I see even today his heroism precisely in this, that he did not concern himself with this risk. He was convinced of what God was asking of him at that moment: “I no longer have the strength to continue my mission, my mission is concluded, I entrust it to someone else who has more energy than I the task of leading the Church.” Because the Church is not of the Pope, but of Christ. He who loves the Church will view such a decision as a great act of government.

Msgr. Alfred Xuereb (right) during the presentation of the book Jesus of Nazareth by Pope Benedict XVI, published by LEV (Vatican Publishing House).

(Katarzyna Artymiak photo).

What was the first reaction to the news?

Xuereb: As he conveyed this news to me, I felt immediately like I should say to him: “No, Holy Father, why not think it over a little longer?”

But I restrained myself and said to myself: “Well, who knows how long he may have been thinking this over!” And it passed through my mind, in a flash, all of those long moments of prayer prior to morning Mass, when he stayed quietly in contemplation.

And I let him speak, and I listened to him, a bit at a loss. Everything was already well thought out, when to make the news public and how. And he said to me: “You will go with the new Pope.” And he repeated that twice, to the point where I was about to say to him: “I would be willing, but who knows whether the new Pope will wish to have me?”

Some observers think that Benedict XVI was a too intellectual Pope, with his head entirely filled with books…

Xuereb: I think of the Pope Emeritus as a person built around two dimensions that could appear to be in contrast, but which truly are complementary. On the one hand he is a giant of the intellect, of theological profundity, of philosophy, liturgy, biblical studies… and on the other hand, thanks to his infancy in a normal family, without idiosyncrasies, in Bavaria, he remained a simple man with the innocent face of a child.

Two different parts that render the personality more complete. And his discretion is a way to not overwhelm the other, indeed, his character is always to make the effort to draw out the good that is in the other person in order to find a harmony. This is the art of relating to others that Benedict XVI taught me.

Could you sum up Benedict XVI in a single word?

Xuereb: I do not wish to sum up Pope Benedict in a single word or phrase, because it would be like trying to enclose an entire city under a glass bowl. But the word that I heard Pope Benedict pronounce most often was: Grazie. Thank you. All the time. We helped him to vest for Mass, we gave him his pectoral cross, and he said, “Grazie!”

Once, when I was Prelate of the Antechamber, we were awaiting a guest in the library, and he permitted me to compliment him for the homily that he had just given. I was profoundly struck by the way that he accepted my words.

First of all, he accepted them. And then, with humility, he lowered his eyes and he said: “Grazie!” From the writings of Benedict XVI we can learn a great deal, because he is a marvelous teacher, but not without choosing him also as a model of life.

(This interview was first published in Italian on the web site korazym.org)

Facebook Comments