His last interview, published posthumously, has ignited the controversy. The leading authorities of the Church have ignored it, with the sole exception of Cardinal Ruini. One more reason to analyze it critically.

Benedict XVI greets Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini during a private meeting at the Vatican on May 27, 2005. (CNS photo)

“Cardinal Martini did not leave us a spiritual testament in the explicit sense of the word. His inheritance is entirely in his life and in his magisterium, and we must continue to draw on it for a long time. He did, however, choose the phrase to be written on his grave, taken from Psalm 119 [118]: ‘A lamp to my feet is your word, a light to my path.’ In this way, he himself has given us the key to interpret his existence and his ministry.”

With these words, spoken on September 3 in the homily at the funeral for his predecessor, Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, the current archbishop of Milan, Cardinal Angelo Scola, revoked the qualification of “spiritual testament” from the interview with Martini published the day after his death by Milan’s daily Corriere della Sera.

Martini’s Last Interview: “The Church is 200 years behind the times”

In effect, if this interview were truly the quintessence of Martini’s legacy for the Church and the world — as those responsible for it want us to believe —the figure of the deceased cardinal would correspond precisely to that label of “anti-Pope” which was applied to him over the years by circles inside and outside of the Church, but which clashes strongly with the lofty and heartfelt attestations of esteem expressed repeatedly toward him by Benedict XVI himself, most recently in his unusual message for the archdiocese of Milan on the day of the funeral of the one who was its archbishop from 1979 to 2002.

The interview was conducted on August 8, three weeks before the death of the cardinal, by the Austrian Jesuit Georg Sporschill, together with an Italian residing in Vienna, Federica Radice Fossati Confalonieri.

Father Sporschill is the same one who in 2008 edited the publication of Martini’s most successful book, also in the form of an interview, Conversazioni notturne a Gerusalemme (“Night Conversations in Jerusalem”).

Photos of then-Cardinal Ratzinger and Cardinal Martini on the cover of Inside the Vatican (February-March 1994). They met that year with leading Jewish rabbis in Jerusalem during a week of interreligious dialogue.

If to this book are added the other book-length interviews published by Martini in recent years, written together with “borderline” Catholics like Fr. Luigi Verzé and the physician Ignazio Marino and bristling with ambiguous or heterodox texts on the beginning and end of life, on marriage and sexuality, the divergence between this cardinal and the last two Popes would appear even more marked.

Among the leading figures of the Church who in recent days have spoken out on the figure of the deceased cardinal, only Cardinal Camillo Ruini, president of the Italian episcopal conference from 1991 to 2007, has mentioned this divergence.

In an interview with Marina Corradi in Avvenire on September 1, to the observation that on topics like artificial fertilization and homosexual unions “Martini seemed more open to the reasoning of some secularist circles” and “publicly expressed positions that were clearly far from those of the Italian bishops’ conference” of which he was part, Ruini responded: “I do not deny it, as I do not conceal that I remain deeply convinced of the soundness of the positions of the bishops’ conference, which are also those of the pontifical magisterium and have a profound anthropological root.”

And in a subsequent interview with Corriere della Sera on September 5, he made these comments on the statement by Martini, in his presumed “spiritual testament,” according to which “the Church is 200 years behind the times”: “In my view, it is necessary to distinguish two forms of distance of the Church from our time,” Ruini said. “One is a true delay, due to the limitations and sins of Churchmen, in particular to the inability to see the opportunities that are opening for the Gospel today. The other distance is very different. It is the distance of Jesus Christ and of his Gospel, and as a result of the Church, from any time, including our own but also that in which Jesus lived. This distance must be there, and it calls us to the conversion not only of persons but also of culture and history. In this sense, today as well, the Church is not farther back, but farther ahead, because in that conversion is the key to a good future.”

But apart from Ruini, no other important Churchman has made reference, in the comments following Martini’s death, to the effectively controversial elements of the figure of Cardinal Martini.

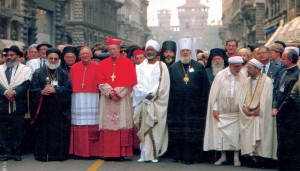

Cardinal Martini, archbishop of Milan, guides a march during the meeting of world religions in Milan in 1994.

The reminiscence has gone exclusively and generically to his merits as a biblicist and pastor, to the School of the Word, to the promotion of charity, to the dialogue with nonbelievers, to the proximity to difficult existential situations.

In other words, the almost exclusive memory has been of Martini as archbishop, not of Martini as opinion leader of recent years, exalted by the secular media as well as by the Catholic proponents of an imaginary Vatican Council III and of a democratized Church.

That is, one has witnessed in recent days a flood of strongly selective commemorations, while an almost universal silence has fallen upon the problematic aspects of the figure and upon his public statements of recent years.

This, however, has not prevented the interview, presented as Martini’s “spiritual testament” and “read and approved” by him, from going around the world, solidifying precisely that image of him as an alternative prophet which the leaders of the Church would like to exorcise.

One more reason to reread and analyze critically Martini’s last, posthumously published interview. You can read the interview here.

Facebook Comments