Pope Francis’ visit to the Great Synagogue of Rome. Pope Francis’ speech to the Jewish Community of Rome.

An American Catholic offers a reflection on the recent statement on Catholic-Jewish relations from the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of Christian Unity

Initial news headlines on the recent document issued by the Vatican Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews were somewhat misleading (such as: “New Vatican document: Catholics should not seek to convert Jews”). The term “convert” in this context is usually used to describe the acceptance of Jesus Christ by Jews, a process which the headline seems to dismiss. But in fact, the document insists that Christians are still to bear witness to the fulfillment of Judaism in Christ.

A somewhat more accurate, but far less interesting, headline might have read something like this: “New Vatican document: Catholics must honor Jewish faith in Old Covenant but witness to Christ as its fulfillment.” Nonetheless, I’ve used the term “conversion” in my title because it draws attention to the difference between what the document says and what many might guess that it says.

The document in question is The Gifts and the Calling of God are Irrevocable (Rom 11:29). Perhaps the first thing that wary readers need to know is that this was not intended to be an exercise of the Magisterium. To quote its own Preface: “The text is not a magisterial document or doctrinal teaching of the Catholic Church, but is a reflection prepared by the Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews on current theological questions that have developed since the Second Vatican Council. It is intended to be a starting point for further theological thought with a view to enriching and intensifying the theological dimension of Jewish-Catholic dialogue.”

The Problem

The problem with the relationship between Christians and Jews is that it is a deep mystery. In the first couple of centuries, many Christians would have had a natural instinct to exclaim: “Come on, old friends. You are so close! All of God’s promises to you are true, so true that they have now been fulfilled in Christ!”

As the centuries passed, however, the Jewish roots of Christianity tended to be undervalued in an overwhelmingly Gentile Church, and Christians too often viewed Jews as a stiff-necked people who had been rejected by God.

It took the post-Christian, semi-pagan horrors of the Holocaust in the 20th century to bring Catholics to the defense of Jews and to fuel a rethinking of the Christian-Jewish relationship. This rethinking went back to Scripture, particularly the Revelation we have received in St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans — most notably in chapters 9-11.

The recovery of a deep respect for the mystery of the Old Covenant was moved to the forefront of Jewish-Christian relations by the Second Vatican Council’s “Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions” (Nostra Aetate). Again, it is the purpose of this new text from the Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews to reflect on the relevant theological questions as they have emerged and clarified themselves since the Council.

It was, after all, St. Paul who said of the Jewish people that “the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable” (Rm 11:29).

Key Points

This new document tells the history of Catholic dialogue with Jews since the Council, underscoring that it has a “special theological status”:

In spite of the historical breach and the painful conflicts arising from it, the Church remains conscious of its enduring continuity with Israel. Judaism is not to be considered simply another religion; the Jews are instead our “elder brothers” (Saint Pope John Paul II), our “fathers in faith” (Benedict XVI). Jesus was a Jew, was at home in the Jewish tradition of his time, and was decisively shaped by this religious milieu. [14]

This has important implications:

Fully and completely human, a Jew of his time, descendant of Abraham, son of David, shaped by the whole tradition of Israel, heir of the prophets, Jesus stands in continuity with his people and its history. On the other hand he is, in the light of the Christian faith, himself God—the Son—and he transcends time, history, and every earthly reality. The community of those who believe in him confesses his divinity (cf. Phil 2:6-11). In this sense he is perceived to be in discontinuity with the history that prepared his coming. From the perspective of the Christian faith, he fulfils the mission and expectation of Israel in a perfect way. [14]

For these reasons, dialogue between Jews and Christians cannot proceed as if these are two fundamentally diverse religions which developed independently or without mutual influence.

Moreover, while it is certainly true that the Church is the new people of God, “the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures” (23, quoted from Nostra Aetate, 4). Ultimately, God does not lie and He is always faithful. The covenant that God offered Israel is irrevocable and God’s elective fidelity is never repudiated.

In this light, any Christian effort to separate the two covenants, rejecting the Old Testament while retaining only the New, is a grave error. This is why Marcion was excommunicated in AD 144. Again, there is a deep mystery in the relationship between the covenants, in the relationship between Judaism and Christianity, and in the relationship between Jews and Gentiles. As St. Paul wrote, “Just as you [Gentile Christians] were once disobedient to God but now have received mercy because of their disobedience, so they have now been disobedient in order that by the mercy shown to you they also may receive mercy” (Rm 11:30-31).

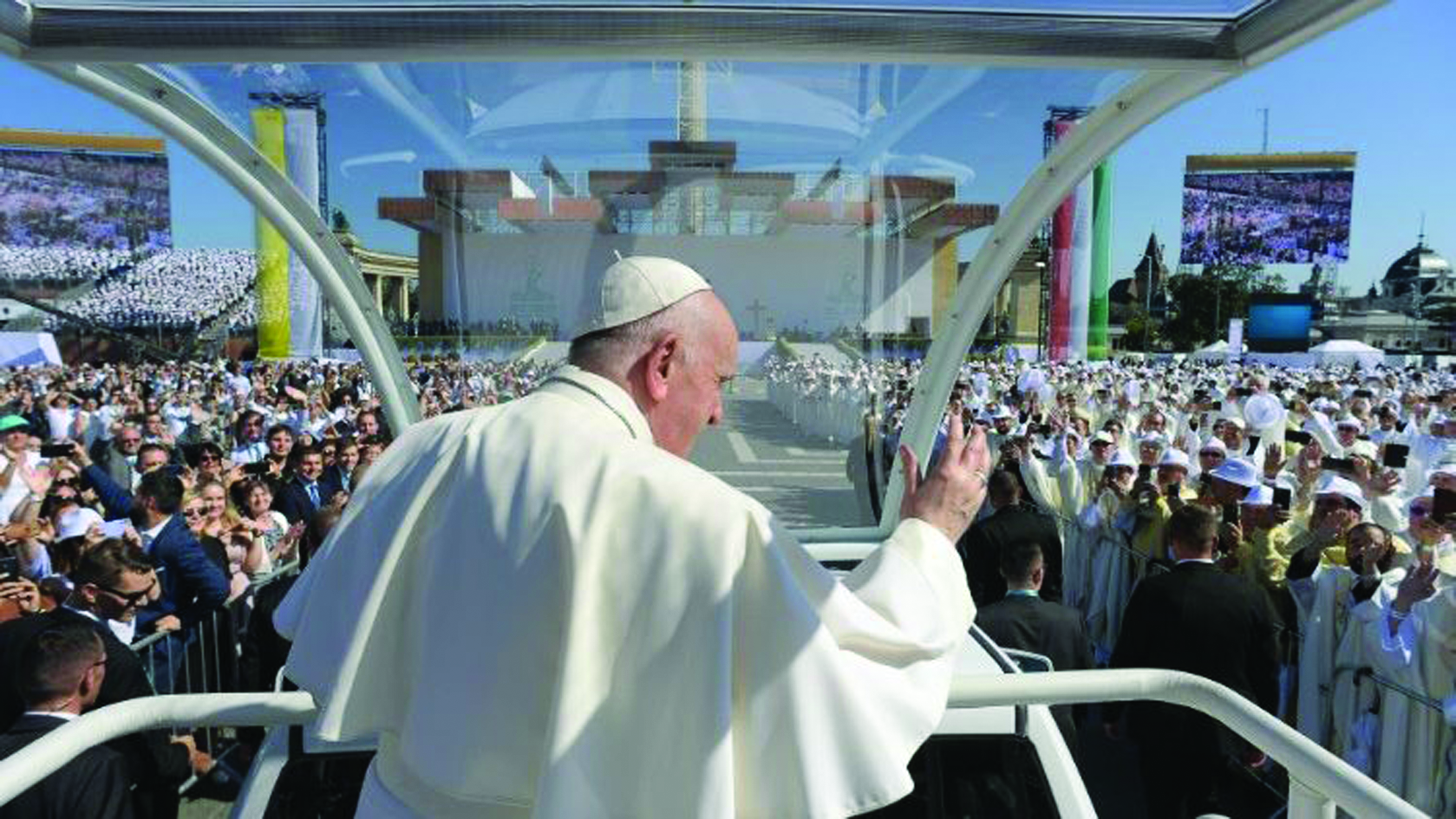

Pope Francis’ visit to the Great Synagogue of Rome

Avoiding Errors

But the text also cautions against two key errors. First, there are not two different but parallel ways of salvation for Christians and Jews: “The Church and Judaism cannot be represented as ‘two parallel ways to salvation,’ but…the Church must ‘witness to Christ as the Redeemer for all.’ The Christian faith confesses that God wants to lead all people to salvation, that Jesus Christ is the universal mediator of salvation, and that there is no ‘other name under heaven given to the human race by which we are to be saved’ (Acts 4:12).”(35)

Second, Jews are in fact called to membership in the Church: “The people of God attains a new dimension through Jesus, who calls his Church from both Jews and Gentiles (cf. Eph 2:11-22) on the basis of faith in Christ and by means of baptism, through which there is incorporation into his Body which is the Church” (41). And, “It is and remains a qualitative definition of the Church of the New Covenant that it consists of Jews and Gentiles, even if the quantitative proportions of Jewish and Gentile Christians may initially give a different impression” (42).

So where does this leave us? The Church must view evangelization of the Jews “in a different manner from… people of other religions and world views” (40). The text notes that the Church “neither conducts nor supports any specific institutional mission work directed towards Jews” — and, in fact, it is instructive to reflect that the Church has never, over 2,000 years of history, done this. This is highly suggestive that such a stance is part of her DNA.

But the call to evangelization must not be denied: “While there is a principled rejection of an institutional Jewish mission, Christians are nonetheless called to bear witness to their faith in Jesus Christ also to Jews” (40) and “Christian mission means that all Christians, in community with the Church, confess and proclaim the historical realization of God’s universal will for salvation in Christ Jesus” (42).

The upshot is that the Church uses a more nuanced language in speaking of her relationship with the Jews. It is not a question of “conversion” away from the Old Covenant, the law and the promises. Still less is it a question of hostility and rejection. It is rather a question of fulfillment in Christ. The Church does not see Judaism as a foreign and false religion, but as the root of her own development — a root which, for a mysterious reason, has not yet realized its fulfillment in Christ.

Jeffrey Mirus holds a Ph.D. in intellectual history from Princeton University. A co-founder of Christendom College, he also pioneered Catholic Internet services. He is the founder of Trinity Communications and CatholicCulture.org, where this article originally appeared.

“The Logic of Peace”

“The violence of man toward man is in contradiction with every religion worthy of this name, and in particular with the great monotheistic religions,” Pope Francis said in his talk at Rome’s Great Synagogue during a January 17 visit. “Life is sacred, a gift from God,” he said. “The Fifth Commandment of the Decalogue says, ‘Do not kill.’ God is the God of life and always seeks to promote and defend it; and we, created in his image and likeness, are required to do the same.” “Every human being, as a creature of God, is our brother, independent of his origin or religious practice,” he said, recalling that God “extends his merciful hand to all, independent of their faith and their origin,” and “cares for those who need him the most: the poor, the sick, the marginalized, the defenseless.” “We must pray to him insistently so that he helps us to practice in Europe, in the Holy Land, in the Middle East, in Africa, and in every other part of the world, the logic of peace, reconciliation, forgiveness and life.”—CNA

Facebook Comments