[…] In the 1980s, within the Council for Public Affairs, today the section for relations with states of the secretariat of state, there was an “office for pontifical mediation.”

Its aim was to lay the juridical-political foundation to put an end to the territorial disputes between Argentina and Chile over the Beagle Channel, at the southern tip of the American continent. An objective that was actually reached on November 29, 1984 with the conclusion of the treaty of peace and friendship through which the parties put into binding terms the solution of the dispute proposed by the Holy See.

Such peacemaking activity was already of longstanding date, as recalled by the arbitration conducted by Pope Leo XIII in 1885 to put an end to the conflict between Spain and Germany over the sovereignty of the Caroline Islands, and continuing to the very recent opening of new relations between Cuba and the United States after decades of nothing but opposition.

For those who might wish to interpret these events apart from the ecclesial dimension, it should be enough to recall that in the aforementioned cases it was the local episcopates and in any case the presence and role of the Church in those countries that saw a diplomatic intervention of the Holy See as essential.

To pontifical diplomacy, therefore, is entrusted the task of working for peace by following the methods and rules that are proper to subjects of international law, elaborating concrete responses in juridical terms to prevent, resolve, and regulate conflicts and avoid their possible degeneration into the irrationality of armed force.

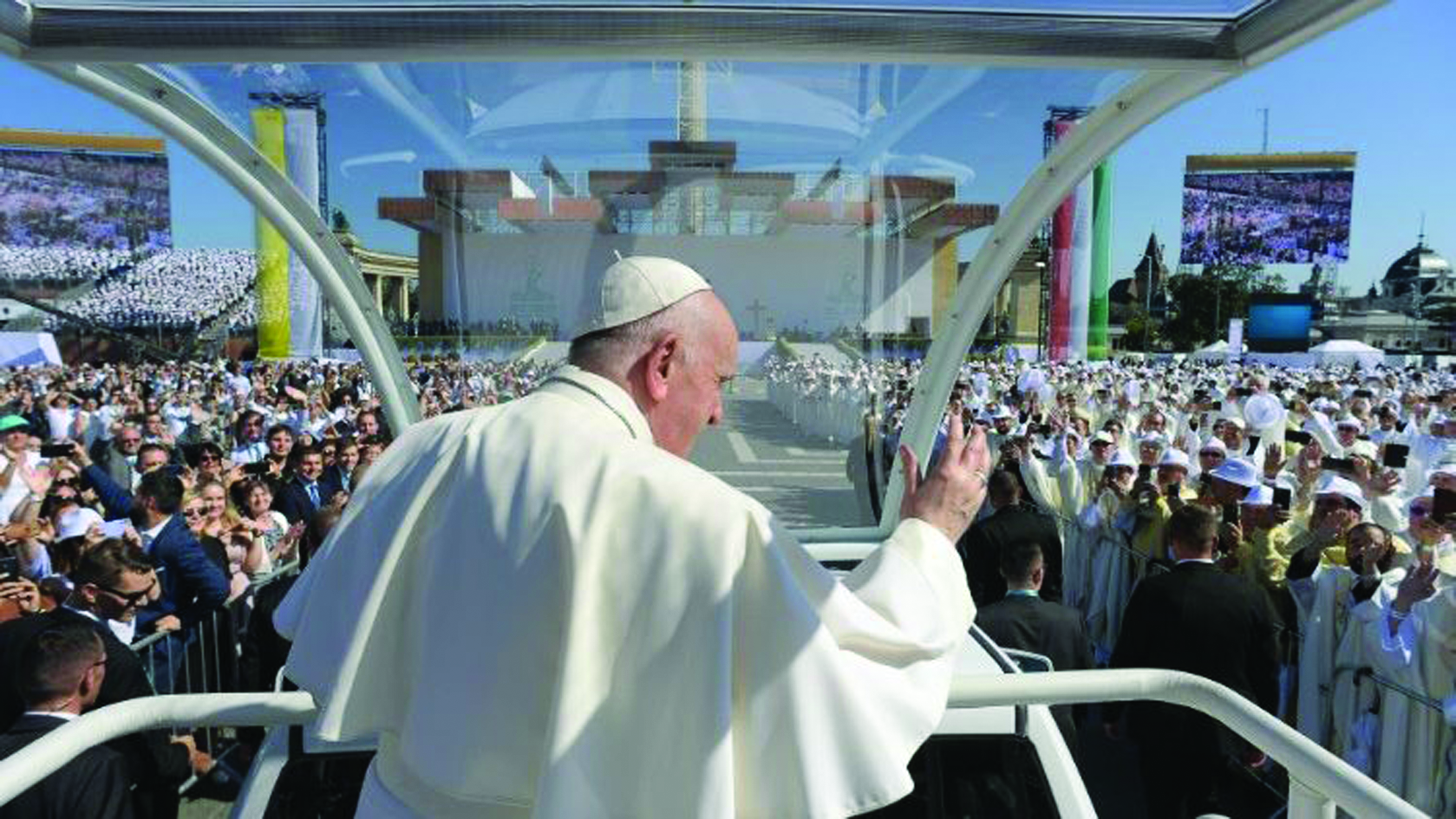

But looking at the substantial profile, this is above all a matter of an action that demonstrates how the end sought should be primarily religious, meaning that it should be situated within being true “peacemakers” and not “warmongers or at least makers of misunderstandings,” as Pope Francis reminds us. An appeal in the face of which the academic context in which we find ourselves allows, and I would say almost imposes, the accompaniment of these reflections with the proposal that in the work of reform undertaken by the Holy Father, room should be found for an “office for pontifical mediation” that could act as a link for the diplomacy that the Holy See is already doing on the ground in the different countries and likewise as a liaison with the activities in this area that the international institutions carry forward. […]

As for the age-old debate over the limits that armed force must have in international relations, I recall only how the two modalities that the international community has identified after the “fall of the walls,” meaning humanitarian intervention and the responsibility to protect, found consideration respectively in the speeches of John Paul II to the FAO in 1992 and of Benedict XVI to the United Nations in 2008.

The dangers for peace and the threats to security, however, impose a search for additional tools and ways of acting, at least in order to face a changed scenario: it is sufficient to recall that the delocalized terrorism that asserted itself with September 11, 2001, has today been replaced by an “extra-territorial” terrorism issuing from territorially localized entities and even coming to the point of using the instruments proper to state activities.

Disarming the aggressor in order to protect persons and communities is not a matter of ruling out the extreme measure of legitimate defense, but of considering it as such — truly an extreme measure! — and above all of using it only if the desired result and its reasonable probability of success are clear. Here I am recalling not only a constant of Church teaching, but also those norms of international law which have overcome the conviction according to which the use of armed force can only be humanized, not eliminated.

It therefore becomes necessary not to limit oneself to understanding the causes of each act of aggression, but to addressing and resolving it according to the principle of good faith. The history of diplomacy narrates numerous episodes in which for two or more adversaries the territory of a third state becomes the place for playing out their respective interests, forgetting the rights of the resident populations, who become innocent victims or are subjected to forced relocation. Likewise the diplomat intuits the consequences of supplying arms in a conflict or in an unstable region, as also of the guarantee to dispose of and utilize economic resources. All of this is perhaps cloaked in justifications of a strategic, economic, ethnic, cultural, or even religious nature. In the absence of a determination to halt these situations, the risk of extending the spiral of conflicts and the destabilization of entire areas is certain, but peace does not come from bombs or from the domination of one over the other.

More generally, then, the search for new paths means entrusting the solution of disputes to peaceful means, including those which, for example, involve the obligatory intervention of the international court.

One theme dear to pontifical diplomacy was already shown by Leo XIII in a letter to Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands dated February 11, 1899, while the Hague Convention was finalizing the idea of a permanent court of arbitration. John Paul II revisited the contents of that letter in an unforgettable speech to the International Court of Justice in 1988, calling for a “legal criterion of individual and criminal responsibility toward the international community” that would find its fulfillment ten years afterward with the institution of the International Criminal Court.

The question is: if within states a centralized judicial function has overcome vengeance and retaliation, can the same thing not happen in the society of states? Perhaps it is necessary that our role as builders of peace should become active in proposing ideas that could then contribute to defining new scenarios and procedures for peace.

As I indicated at the beginning of these reflections, in the “word cloud” of the term peace there are also other situations and questions. And these have to do with the diplomatic action of the Holy See, when it presents itself within the context of international institutions.

They are places in which work is done not only to attain peace, but also to develop a culture of peace through the different sectors of international relations. This is an interesting process that the Holy See has followed from the beginning and that, in the light of experience, allows the observation that the norms and programs of the international bodies are not so far after all from the everyday life of persons, communities, and peoples, but orient their behaviors and suggest ways of life.

We could say that the multilateral dimension of international relations, with their ever more complex methods and regulations, is itself part of the global dimension that characterizes our time.

For the diplomacy of the Holy See, the challenge is twofold. On the one hand it feels obligated to an effort of formation and preparation, recognizing that one cannot operate in intergovernmental institutions without the necessary competence, technical capacity, and true professionalism. On the other, as an ecclesiological instrument, it must evaluate “if and how” what emerges in those contexts responds to the good of the human family and is not limited to particular interests that could easily overturn the very guidelines and programs set up for the sake of peace.

Such a roadmap is necessarily connected to the prevention not only of conflicts and wars, but more and more to the protection of human dignity and the rights connected to it. The priority then goes to factors like poverty, underdevelopment, natural catastrophes, economic crises, and other solutions that can disturb peace or make it impossible.

For pontifical diplomacy, the call for human dignity leads to the theme of freedom of religion as a multifaceted right that spans from questions connected to acts of worship to the need to recognize the capacity of every religious community for autonomous organization.

In this area the diplomatic relations of the Holy See with states are aimed at guaranteeing the libertas ecclesiae, while multilateral action tends above all to situate the religious dimension within the efforts for peaceful coexistence among peoples and among states.

If exactly forty years ago the Holy See worked to have the right to religious freedom included in the Helsinki Final Act among the ten cardinal principles of renewed and peaceful international relations, at this moment the objective of its diplomatic activity is to overcome an instrumental use of religion, which even arrives at considering it a justification for all kinds of hatred, persecution, and violence.

But today as in 1975, one element remains constant: in its activities the Holy See has at heart the condition of all believers. A commitment that becomes a challenge at a moment in which it is well documented that Christians are among the most discriminated against and there continue to be laws, decisions, and behaviors that are intolerant toward the Catholic Church and other Christian communities.

This challenge necessarily begins by considering dialogue preeminent, as demonstrated for example by the support for the idea of structuring dialogue among religions on the basis of the institutions and norms of international law that since October 31, 2012 has seen the Holy See as a participant, as a founding observer of the International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue (KAICIID), an intergovernmental organization headquartered in Vienna. […]

English translation by Matthew Sherry, Ballwin, Missouri, U.S.A.

Facebook Comments