April 23, 2017, Sunday, Divine Mercy Sunday

“Christian liturgy is a liturgy of promise fulfilled, of a quest, the religious quest of human history, reaching its goal. But it remains a liturgy of hope. It, too, bears within it the mark of impermanence. The new Temple, not made by human hands, does exist, but it is also still under construction. The great gesture of embrace emanating from the Crucified has not yet reached its goal; it has only just begun. Christian liturgy is liturgy on the way, a liturgy of pilgrimage toward the transfiguration of the world, which will only take place when God is ‘all in all.'” —Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, The Spirit of the Liturgy, 1999

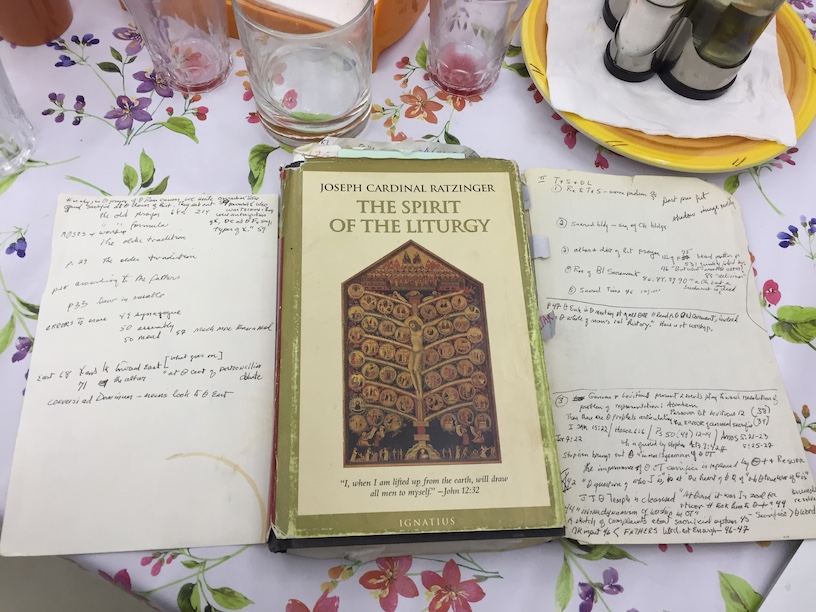

An old book filled with hand-written notes

I am writing just before, and just after, midnight from a Maronite monastery on the edge of Rome on the night of Divine Mercy Sunday, toward the end of April in 2017.

Before me on the table is book once owned by my father, William Moynihan, who is now 90 years old — the same age as Emeritus Pope Benedict, whose 90th birthday fell on Easter Sunday, one week ago.

The last time I was at my parents’ home, in March, my father told me to begin to take away some of his books.

“Take whichever ones you want,” he said. “That will leave fewer for when the time comes…”

I looked at the books in his library, and found one filled with his handwritten notes, underlinings, brackets for key passages, checkmarks here and there.

The book also contains a dozen notecards, sticking out, each filled with his handwritten notes.

And there are several dozen little rectangles of paper pasted into the corners of pages, like notebook tabs, to open the book at places where my father evidently thought the text was expecially important, eloquent or profound.

Here is a picture of the book, and two pages of notes beside it…

It is a well-read book, well-thumbed, read and re-read by my father, annotated by him over nearly 20 years since its publication in 1999.

This book by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger is about the liturgy of the Church, the Church’s formal thanksgiving to God for his goodness and mercy.

My eyes fall on the final lines of Part 1, entitled “The Essence of the Liturgy,” where Ratzinger writes the words with which I begin this letter: “Christian liturgy is a liturgy of promise fulfilled, of a quest… Christian liturgy is liturgy on the way, a liturgy of pilgrimage toward the transfiguration of the world, which will only take place when God is ‘all in all.'”

Let us read even more slowly.

A liturgy of promise fulfilled….

A liturgy of a quest….

A liturgy on the way…

A liturgy of pilgrimage…

A liturgy of pilgrimage toward the transfiguration of the world…

A liturgy of pilgrimage toward the transfiguration of the world, which will only take place when God is “all in all.”

I do not want to keep this book my father annotated, only borrow it, to read it, to understand it, and then return it to him, in a year or three…

Will that be enough time to understand it?

From Norcia to Rome via San Giovanni Rotondo and Monte Cassino

If Christian liturgy is a liturgy of a quest, is the Christian faith a faith of quest?

If the Christian liturgy is a liturgy of pilgrimage, is the Christian faith a faith of pilgrimage?

If our faith is in fact a faith of quest and pilgrimage, then perhaps we must embark upon a quest, or upon a pilgrimage, in order to grasp our faith, to enter into our faith, to live in and by and through it.

So perhaps a good way to begin to understand our liturgy and our faith (“lex orandi lex credendi” — “the law of praying is the law of believing,” that is, the way we pray, the way we worship, is the way we believe) is to set out on a quest, or a pilgrimage.

And so in these days I have made a journey which seems to have some aspects of a quest, or of a pilgrimage…

Before Easter, I went to Terni, to Foligno, to Assisi, to the Portiuncula in Santa Maria degli Angeli, to Norcia, to Chieti, to Franca Villa, Pescara, Lanciano, Vasto, San Giovanni Rotondo and to the grotto of the Archangel Michael on Mount Gargano, overlooking the Adriatic, and then by way of Foggia and Benevento to Monte Cassino, and finally, to Rome…

In Norcia, I visited the Benedictine monks, as I mentioned in my last letter. I was there on Holy Thursday, and the liturgy included the washing of the feet of the monks by the new prior, Father Benedict, who washed even the feet of the former prior, Father Cassian Folsom, both Americans.

And in the main square of a mostly silent Norcia in Holy Week, in mid-April of 2017, I observed the town’s bell tower held together by straps, and the basilica in rubble except for the facade.

Here is a picture of that scence, on Holy Thursday, 10 days ago.

And as I gazed upon the ruined tower, wondering whether I might with my own breath, or cough, send it crashing down — for you can see that that the tower is tilted, and cannot possibly stand for long, even with the straps they have bound it with — I sensed the fragility and transience of all human constructions in this world.

I drove out of the city and up the hill. It was still an hour before the beginning of Holy Thursday liturgy. I stretched out on the hillside overlooking Norcia and waited for the opening of the gates to the monastery. The hillside was blooming with April flowers.

The monks came to greet me.

They told me that the archbishop of Spoleto, Renato Boccardo, age 64 — who has jurisdiction over Norcia — has decided that he will bebuild the Basilica of St. Benedict in a modern style of architecture. He will also take possession of the quarters where the monks had been living from the year 2000 until October 2016. He will use the quarters as a part-time episcopal residence.

So the Benedictine monks of Father Cassian will not return to the center of Norcia, to the spot where St. Benedict and his twin sister St. Scholastica were born. That period of the monastery’s life is over now, it seems. The monastery will now be built on the hillside above the city, about two miles outside of the city walls.

As I reflected on these things, I made a mental note to myself to read Rod Dreher’s important new book, The Benedict Option, to see what this American convert to Orthodoxy has to say about the overarching predicament of modern man, of Western man, of post-Christian, post-liturgical man…

For an introduction to Dreher’s book, go here.

And to gain a sense of the book, consider these passages from Dreher’s chapter on sexuality and Christianity (passages which also shed light on why the teaching on marriage, sexuality and sacramentality by recent Popes, including Pope Francis in Amoris Laetitia, has been at once so important and so controversial):

“Wendell Berry has written, ‘Sexual love is the heart of community life. Sexual love is the force that in our bodily life connects us most intimately to the Creation, to the fertility of the world, to farming and the care of animals. It brings us into the dance that holds the community together and joins it to its place.'”

Dreher continues:

“This is more important to the survival of Christianity than most of us understand. When people decide that historically normative Christianity is wrong about sex, they typically don’t find a church that endorses their liberal views. They quit going to church altogether.

“This raises a critically important question: Is sex the linchpin of Christian cultural order? Is it really the case that to cast off Christian teaching on sex and sexuality is to remove the factor that gives — or gave — Christianity its power as a social force?

“Though he might not have put it quite that way, the eminent sociologist Philip Rieff would probably have said yes. Rieff’s landmark 1966 book The Triumph of the Therapeutic analyzes what he calls the ‘deconversion’ of the West from Christianity. Nearly everyone recognizes that this process has been under way since the Enlightenment, but Rieff showed that it had reached a more advanced stage than most people — least of all Christians — recognized.

“Rieff, writing in the 1960s, identified the Sexual Revolution — though he did not use that term — as a leading indicator of Christianity’s demise. In classical Christian culture, he wrote, ‘the rejection of sexual individualism’ was ‘very near the center of the symbolic that has not held.’

“He meant that renouncing the sexual autonomy and sensuality of pagan culture and redirecting the erotic instinct was intrinsic to Christian culture.

“Without Christianity, the West was reverting to its former state.

“It is nearly impossible for contemporary Americans to grasp why sex was a central concern of early Christianity. Sarah Ruden, the Yale-trained classics translator, explains the culture into which Christianity appeared in her 2010 book Paul Among the People. Ruden contends that it’s profoundly ignorant to think of the Apostle Paul as a dour proto-Puritan descending upon happy-go-lucky pagan hippies, ordering them to stop having fun.

“In fact, Paul’s teachings on sexual purity and marriage were adopted as liberating in the pornographic, sexually exploitive Greco-Roman culture of the time — exploitive especially of slaves and women, whose value to pagan males lay chiefly in their ability to produce children and provide sexual pleasure. Christianity, as articulated by Paul, worked a cultural revolution, restraining and channeling male eros, elevating the status of both women and of the human body, and infusing marriage — and marital sexuality — with love.

“Christian marriage, Ruden writes, was ‘as different from anything before or since as the command to turn the other cheek.’

“Chastity — the rightly ordered use of the gift of sexuality — was the greatest distinction setting Christians of the early Church apart from the pagan world.

“The point is not that Christianity was only, or primarily, about redefining and revaluing sexuality, but that within a Christian anthropology sex takes on a new and different meaning, one that mandated a radical change of behavior and cultural norms.

“In Christianity, what a person does with their sexuality cannot be separated from what a person is. In a sense, moderns believe the same thing, but from a perspective entirely different from the early Church’s.

“In speaking of how men and women of the early Christian era saw their bodies, historian Peter Brown says the body was embedded in a cosmic matrix in ways that made its perception of itself profoundly unlike our own.

“Ultimately, sex was not the expression of inner needs, lodged in the isolated body. Instead, it was seen as the pulsing, through the body, of the same energies as kept the stars alive. Whether this pulse of energy came from benevolent gods or from malevolent demons (as many radical Christians believed) sex could never be seen as a thing for the isolated human body alone.

“Early Christianity’s sexual teaching does not only come from the words of Christ and the Apostle Paul; more broadly, it emerges from the Bible’s anthropology. The human being bears the image of God, however tarnished by sin, and is the pinnacle of an order created and imbued with meaning by God.

“In that order, man has a purpose. He is meant for something, to achieve certain ends.

“When Paul warned the Christians of Corinth that having sex with a prostitute meant that they were joining Jesus Christ to that prostitute, he was not speaking metaphorically. Because we belong to Christ as a unity of body, mind, and soul, how we use the body and the mind sexually is a very big deal.

“Anything we do that falls short of perfect harmony with the will of God is sin. Sin is not merely rule breaking but failing to live in accord with the structure of reality itself…”

Norcia to Monte Cassino

As I wrote in the last letter, I went to Chieti on Good Friday, and observed the Good Friday procession that begins in the cathedral, passes through the streets of the city, and returns to the cathedral.

In this way, the faith is visible, not vilified, in public.

On Holy Saturday, I went to Lanciano, where a Eucharistic miracle occurred more than 1,300 years ago. Today, two stone angels flank the reliquary containing the miraculous bread and wine (one can be seen on the lower right).

For the Vigil of Easter, I attended Mass in the cathedral of Pescara. There the community is deeply influenced by the Neo-Catechumenate Way. There was a loud, amplified guitar, and much clapping.

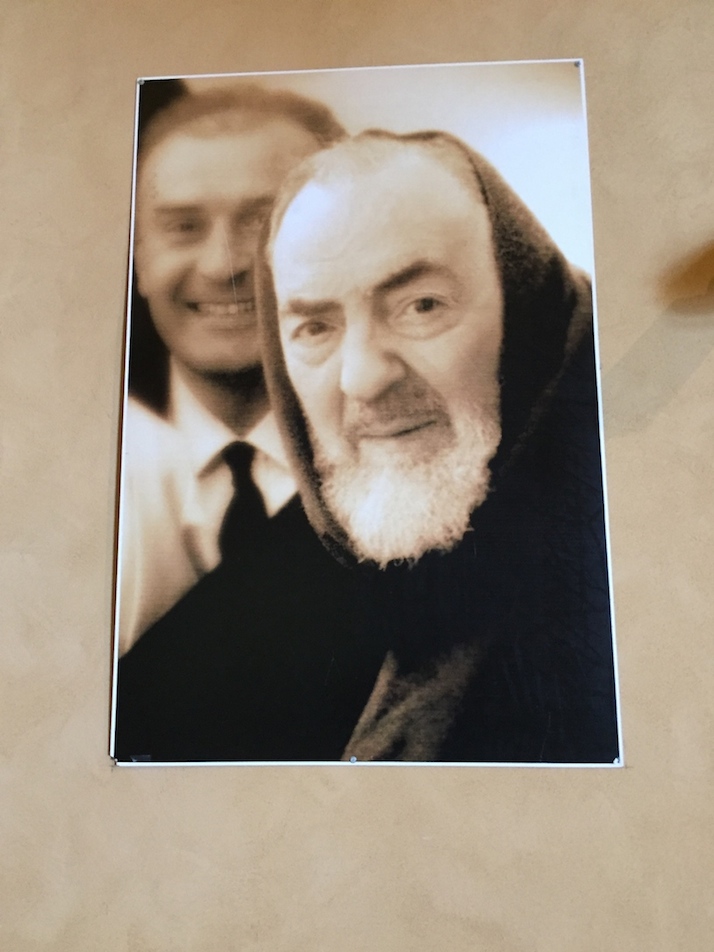

I drove on Easter Sunday to San Giovanni Rotondo, to visit the tomb of St. Padre Pio, who died in 1968.

He was a Capuchin Franciscan, and his life in many ways mirrored the life of St. Francis of Assisi, as narrated by a series of mosaics near his tomb. His body bore the signs of Christ’s wounds, the stigmata.

He is buried beneath a modern church with many curving pillars and arches which, to me, seems architecturally not in keeping with the spirit of the man.

Here is an image of his tomb.

I then drove to the grotto of the Archangel Michael, a splendid sanctuary dating from more than 1,000 years ago, which looks out over the curving coastline of Apulia for what seems like 100 miles. Here the Lombard and Norman soldiers came during the early and later Middle Ages.

Mass was celebrated here in the grotto, dozens of meters underground.

I drove past Foggia, where in the Second World War an estimated 20,000 Italian civilians were killed during allied bombardments on July 22 and August 19 in 1943. (link)

I reached Monte Cassino on Easter Monday.

Here St. Benedict, who was born in about 480 A.D., in the middle 500s wrote his Benedictine Rule and spent the last years of his life. He died here on March 21 in 543 or 547, at the age of 63 or 67, when the region had been conquered by the Ostrogoths.

Here is a view of part of the monastery from the doorway of the main church, looking out for miles over the central Italian countryside.

I bought books in Monte Cassino to study the history of the place. I was told that many civilians who were being held as hostages in the monastery by the Germans were killed when Monte Cassino was bombed in the Second World War. The entire monastery was reduced to rubble, but after the war it was rebuilt to look exactly as it once did.

Saturday and Sunday, Vigil and Feast of Divine Mercy

Yesterday in Rome, Saturday, from 10 until 4, there was a conference in the Hotel Columbus where six speakers from five continents, all laypeople, spoke abut the concern they feel over the doctrinal confusion they believe has been caused by the Apostolic Exhortation of Pope Francis published about a year ago, Amoris Laetitia.

About 125 people attened the conference, which was free.

Here is a photo of the afternoon session.

Gerard O’Connell of America magazine, who may be seen in the photo above in the back row, second person in the row, with earphones on, wrote an account of what occurred for America (link to America article)

This morning is Rome, the Feast of Divine Mercy, an English-language Mass usually held on the Church of Santo Spirito was moved to the Church of San Lorenzo very close to St. Peter’s Square (the Pope’s cardinal vicar for Rome, Agostino Vallini, celebrated Divine Mercy Mass in Santo Spirito, which is the sanctuary dedicated to Divine Mercy in the city).

In San Lorenzo, Father Geno Silva, an American priest from New Jersey who has been working for several years in the Vatican Council for the New Evangelization (which played a major role in organizing the events of the Jubilee of Mercy) delivered a profound, eloquent sermon.

He spoke of traveling recently to Cairo, Egypt, and of seeing great poverty but also great joy in the life of the faithful in the midst of that poverty.

He urged all of us to be transformed by the renewing of our minds to discern God’s will and find true joy doing that will, as St. Paul in Romans 12:2 urges: “And be not conformed to this world: but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, that you may prove what is the good, and acceptable, and perfect will of God.”

Here is a moment just before the consecration during this morning’s Mass.

Now I turn to the book of my father, the book on the liturgy.

It is in front of me now…

(to be continued)

If you would like to travel with me to Russia and Rome in July on our 4th Annual Urbi et Orbi Foundation Pilgrimage, please email [email protected].

If you would like to travel with us to England in the footsteps of St. Thomas More, please write to [email protected] for more information.

Please consider subscribing to Inside the Vatican.

Note: The Moynihan Letters go to some 20,000 people around the world. If you would like to subscribe, click here to sign up for free. Also, if you would like to subscribe to our print magazine, Inside the Vatican, please do so! It would support the old technology of print and paper, as well as this newsflash. Click here.

What is the glory of God?

“The glory of God is man alive; but the life of man is the vision of God.” —St. Irenaeus of Lyons, in the territory of France, in his great work Against All Heresies, written c. 180 A.D.

Facebook Comments