After his environmental encyclical provoked criticism in some circles in the US, the Pope feels he should study those critiques before he travels to the States…

Bolivian President Evo Morales presents a controversial gift to Pope Francis at the government palace in La Paz, Bolivia, on July 8. The gift was a wooden hammer and sickle — the symbol of communism — with a figure of a crucified Christ (CNS photo/L’Osservatore Romano).

Before arriving in the United States in September, Pope Francis has said, he will study American criticisms of his critiques of the global economy and finance.

“I have heard that some criticisms were made in the United States — I’ve heard that — but I have not read them and have not had time to study them well,” the Pope told reporters traveling with him from Paraguay back to Rome on July 12.

“If I have not dialogued with the person who made the criticism,” Francis said, “I don’t have the right” to comment on what the person is saying.

Pope Francis said his assertion in Bolivia on July 9 that “this economy kills” is something he believes and has explained in his exhortation The Joy of the Gospel and more recently in his encyclical on the environment. In the Bolivia speech to grassroots activists, many of whom work with desperately poor people, the Pope described the predominant global economic system as having “the mentality of profit at any price with no concern for social exclusion or the destruction of nature.”

Asked if he planned to make similar comments in the United States despite the negative reaction his comments have drawn from some US pundits, politicians and economists, Pope Francis said that now that his trip to South America has concluded, he must begin “studying” for his September trip to Cuba and the United States; the preparation, he said, will include careful reading of criticisms of his remarks about economic life.

Spending almost an hour answering questions from journalists who traveled with him July 5-12 to Ecuador, Bolivia and Paraguay, Pope Francis also declared that he had not tried coca leaves — a traditional remedy — to deal with the high altitude in Bolivia, and he admitted that being asked to pose for selfies makes him feel “like a great-grandfather — it’s such a different culture.”

The Pope’s trip to Cuba and the United States September 19-27 was mentioned frequently in questions during the onboard news conference. US President Barack Obama and Cuban President Raul Castro publicly thanked Pope Francis and the Vatican last December for helping them reach an agreement to begin normalizing relations.

Pope Francis insisted his role was not “mediation.” In January 2014, he said, he was asked if there was some way he could help. “To tell you the truth, I spent three months praying about it, thinking what can I do with these two after 50 years like this.” He decided to send a cardinal — whom he did not name — to speak to both leaders.

“I didn’t hear any more,” he said.

“Months went by” and then one day, out of the blue, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, Vatican Secretary of State, told him representatives of the two countries would be having their second meeting at the Vatican the next day, he said. The new Cuba-US relationship was the result of “the good will of both countries. It’s their merit. We did almost nothing,” the Pope said.

Asked why he talks so much about the rich and the poor and so rarely about middle-class people who work and pay taxes, Pope Francis thanked the journalist for pointing out his omission and said, “I do need to delve further into this magisterium.”

However, he said he speaks about the poor so often “because they are at the heart of the Gospel. And, I always speak from the Gospel on poverty — it’s not that it’s sociological.”

Pope Francis answers questions from journalists aboard his flight from Paraguay to Rome on July 12 (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

Pope Francis was asked about his reaction to the crucifix on top of a hammer and sickle — the communist symbol — that Bolivian President Evo Morales gave him July 8. The crucifix was designed by Jesuit Father Luis Espinal, who was kidnapped, tortured and killed in Bolivia in 1980.

The Pope said the crucifix surprised him. “I hadn’t known that Father Espinal was a sculptor and a poet, too. I just learned that these past few days,” he said. Pope Francis said that he did know, however, that Father Espinal was among the Latin American theologians in the late 1970s who found Marxist political, social and economic analysis helpful for understanding their countries and their people’s struggles and that the Jesuit also used Marxist theories in his theology. It was four years after the Jesuit’s murder that the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith said plainly that Marxist theory had no place in a Catholic theology, the Pope pointed out.

Father Espinal, he said, “was a special man with a great deal of geniality.”

The crucifix, the Pope said, obviously fits into the category of “protest art,” which some people may find offensive, although he said he did not.

“I’m taking it home with me,” Pope Francis said.

In addition to the crucifix, Morales had given the Pope two honors, one of which was making him part of the Order of Father Espinal, a designation that comes with a medal bearing a copy of the hammer-and-sickle crucifix.

Pope Francis said he’s never accepted such honors; “it’s just not for me,” he said.

But Morales had given them to the Pope with “such goodwill” and such obvious pleasure at doing something he thought would please the Pope that the Pope said he could not refuse.

“I prayed about this,” the Pope told reporters.

He said he did not want to offend Morales and he did not want the medals to end up in a Vatican museums storeroom. So he placed them at the feet of a statue of Mary and asked that they be transferred to the national shrine of Our Lady of Copacabana.

Pope Francis also was asked about his request in Guayaquil, Ecuador, that people pray for the October Synod of Bishops on the family “so that Christ can take even what might seem to us impure, scandalous or threatening, and turn it — by making it part of his ‘hour’ — into a miracle.”

The Pope told reporters, “I wasn’t thinking of any point in particular,” but rather the whole range of problems afflicting families around the world and the need for God’s help for families.

Lessons from South America

How To Greet and Understand Pope Francis

—Cindy Wooden (CNS)

People make special preparations for welcoming a special guest, and watching what worked and did not work in Ecuador, Bolivia and Paraguay may help people preparing for Pope Francis’ visit to the United States in September.

Some of the plans, however, will require common-sense adjustments, especially because the U.S. Secret Service is likely to frown on certain behavior, like tossing things to the Pope — a phenomenon that occurs much more often with Pope Francis than with any previous Pope. At the Vatican, the items tend to be soccer jerseys and scarves; in Ecuador, it was flower petals — lots of them.

Watching the Pope July 5-12 in South America it is clear:

— Pope Francis loves a crowd. He walks into events with little expression on his face, then lights up when he starts greeting, blessing, kissing and hugging people. Persons with disabilities, the sick and squirming babies come first.

— The Pope does not mind being embraced, but he does not like people running at him. As a nun in Our Lady of Peace Cathedral in La Paz rushed toward Pope Francis July 8, the Pope backed up and used both hands to gesture her to calm down and step back. In the end, she did get a blessing from him, though.

— At Mass, Pope Francis tends to be less animated. His focus and the focus he wants from the congregation is on Jesus present in the Eucharist. At large public Masses on papal trips, he sticks to the text of his prepared homilies, although he may look up and repeat phrases for emphasis.

— A meeting with priests, religious and seminarians is a fixture on papal trips within Italy and abroad; in Cuba and the United States, the meetings will take place during vespers services, September 20 in Havana and September 24 in New York. At vespers, like at Mass, Pope Francis tends to follow his prepared text. However, when the gathering takes place outside the context of formal liturgical prayer, he never follows the prepared text, even if he may hit the main points of the prepared text as he did in Bolivia July 9.

— Pope Francis has said he needs a 40-minute rest after lunch, and his official schedule always includes at least an hour of down time. However, as with his “free” afternoons at the Vatican, the Pope often fills the breaks with private meetings with friends, acquaintances or Jesuits. In fact, his trips abroad have always included private get-togethers with his Jesuit confreres, although in South America one of the meetings — in Guayaquil, Ecuador — was a luncheon formally included in the itinerary. But he also spent unscheduled time with Jesuits at Quito’s Catholic university the next day. In Paraguay, he made an unscheduled visit to 30 of his confreres in Asunción and then went next door to their Cristo Rey School to meet with more than 300 students from Jesuit schools.

— In South America, Pope Francis specifically asked that his meetings with the bishops be private, informal conversations — similar to the way he handles the regular ad limina visits of bishops to the Vatican to report on the state of their dioceses. For the ad limina visits, he hands them the text of a rather general look at their country and Catholic community, then begins a discussion. But when he makes a formal speech to a group of bishops, his words can seem critical. But, in fact, the tone tends to be one of addressing his “fellow bishops” and his words are more of a collective examination of conscience than a scolding.

— Pope Francis’ speeches in general — whether to presidents, civic and business leaders, young people or even, for example, the prisoners in Bolivia — acknowledge what is going well and being done right, then seeks to build on that. It’s a combination of a pat on the back and a nudge forward. While Bolivia’s Palmasola Prison is notorious for its difficult conditions and while the Pope pleaded for judicial reform in the country, he also told the prisoners: “The way you live together depends to some extent on yourselves. Suffering and deprivation can make us selfish of heart and lead to confrontation.”

“A Big Hug for the People, in Charity and Solidarity”

Guzmán Carriquiry, secretary of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, reflects on a recent trip to Ecuador, Bolivia and Paraguay

By Patrizia Caiffa (for SIR)

There is an important thread that links the recent visit of Pope Francis in Ecuador, Bolivia and Paraguay and the upcoming, highly-anticipated visit to Cuba in September. The other Latin American countries — primarily Argentina, Uruguay and Chile which he will visit in 2016 — cannot wait to hear him once again speak of embracing them. We spoke with Professor Guzmán Carriquiry, secretary of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, a native of Uruguay, who traveled on the papal plane and now comments on the trip for SIR.

Young people sing as they wait for Pope Francis along the waterfront in Asunción, Paraguay, on July 12 (CNS photo/Paul Haring).

Pope Francis went back to his native Latin America. What did the trip mean?

Professor Guzmán Carriquiry: For Jorge Mario Bergoglio, it must have been deeply moving and gratifying to return to Latin America… and as the Successor of Peter! His popularity is enormous, as is the affection, devotion and trust this popularity arouses. The visit was a big hug for the people in charity and solidarity. The Pope is aware of the great Catholic heritage rooted in the history and culture of the peoples of Latin America, called today to make a quantum leap so that faith becomes even more present in the lives of individuals and of nations. The fundamental purpose of the trip was to strengthen the patrimony of the Catholic faith that is expressed both through popular piety and through feelings of dignity and hope, so that it becomes more and more present. The trip also showed that this is a very favorable time for evangelization in Latin America. It is the responsibility of the entire Latin American Church not to waste this time of grace.

What is the current situation of the Church in Latin America? There is talk of a “Pope Francis effect” in the strengthening of faith …

Carriquiry: It is in a unique situation: more than wanting to present herself as a model, the Church senses her deep responsibility to be moved by the ministry of Pope Francis to respond to this widespread sense of anticipation and opening of hearts. Today many prejudices and resistances have diminished, many people have become reconciled to the Church. There are many conversions, an increase in pilgrimages to shrines. There are more people in the churches and long lines for the confessionals. It is a favorable time for evangelization, which requires much from the pastors of Latin America. I do not like to speak of a model Church, nor do I like idealizations. It is true that the Church in Latin America is a Church of the people because it is very rooted in the people and it has, in this sense, a historical and theological sense of being a Christian people. For Latin Americans the word “people” has deep meaning: it is a common memory, a culture of encounter, a destiny, it is solidarity. Pope Francis is a shepherd who sees and is moved by what he sees, and this leads him to embrace especially the poor. There were very moving encounters with the poor and suffering, such as the one with the homeless in Bagnado on the banks of the Paraguay River. The Pope recalls the Gospel on every occasion, that our relationship with the poor will be what we will be judged upon. He does not follow an ideological “pauperism,” and in fact he has been critical of the ideologies of “enlightened elites” who want everything for the people but not to be with the people, exploiting the poor for their own interests.

How important is popular piety, in this sense?

Carriquiry: We know that the Pope appreciates popular piety. The whole trip was marked by these forms of expression, which for Latin Americans are not religious folklore but modes of inculturation of the faith. The shrines, for example, are the spiritual capitals of our people. Even as Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Cardinal Bergoglio spoke of “sanctuary-izing” of parishes, turning them into sanctuaries. In this sense we can say that the Pope follows the fundamental directives of Evangelii Gaudium, linked to the document of Aparecida, by the Latin American bishops. Such a Church goes to the heart of the Gospel, full of mercy, compassion, missionary and supportive, with preferential love for the poor.

What was the political importance of the visit to the three countries?

Carriquiry: The Pope also had meetings with the presidents, with the diplomatic corps, with the social and political leaders, but none of this makes the visit a political journey. It is obvious that the Catholic tradition of our peoples must have enough force to embrace all dimensions of the existence of nations. The Pope chose Ecuador, Bolivia and Paraguay because they have been traditionally very poor, with great social inequalities and political instability. They are today “emerging peripheries,” because they are living a process of economic growth, development and modernization that spurred peasants and indigenous peoples from immobility, making them more involved in national citizenship, as the middle classes also have grown. The Pope came to highlight the progress but also to denounce big problems that must still be faced: the persistence of large poverty areas; the lack of development with greater fairness; open political dialogue with the participation of all citizens for the common good; drug trafficking, a violent and corrupting disease that is related to the great demand for drugs coming from the US.

Pope Francis does not like confrontation. He recalled that one should not build walls but bridges, and nourish the culture of meeting for the common good. Through this political dialogue, democracy is called to a process of maturity, which goes beyond excessive personalisms and fosters plural contributions.

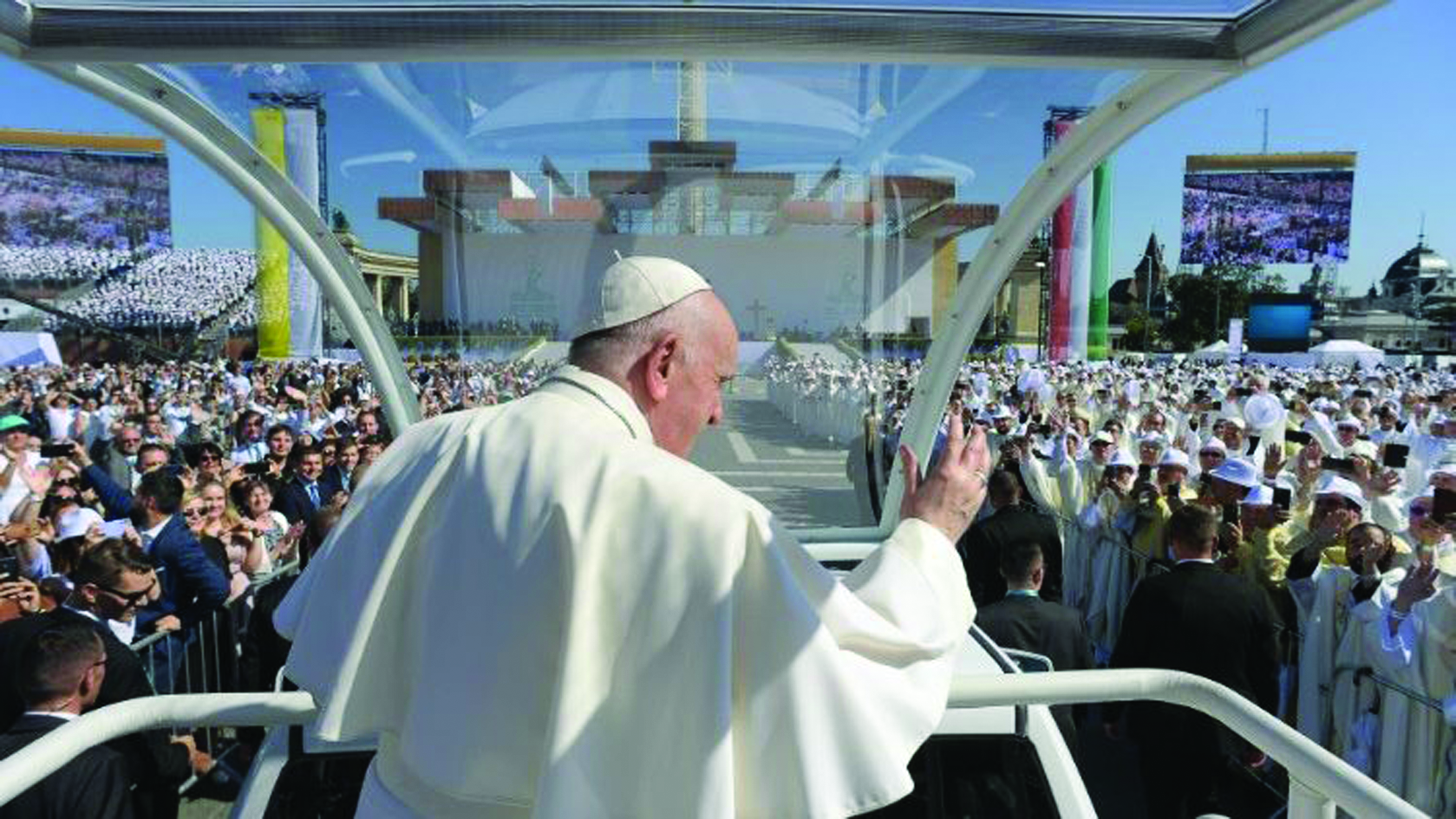

Pope Francis celebrates Mass in Nu Guazu Park in Asunción, Paraguay, on July 12 (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

Pope Francis had strong words against “the economy that kills” in his speech to the popular movements, in Santa Cruz in Bolivia…

Carriquiry: It was the toughest speech, and it had a political dimension. It is not easy to meet popular movements, there is a great diversity among them: some organize themselves in special areas to respond to their particular needs, such as building houses, organization of marginal districts, recycling materials. But many are politicized and still ideological, ready to struggle for power. In that meeting, the Pope attempted to make a bold reinterpretation of the social thought of the Church, in the light of popular movements. He cited the many situations of violence of landless peasants, of homeless families, unemployed youth, street children, women raped, with the sorrowful eyes of a pastor who recognizes how all this is linked to an economic system that kills, causes social exclusion and destroys the environment. The Pope points out the faceless economy that idolizes money, that seeks disproportionate profits at all costs and is expressed through financial and transnational corporations. Of course, the Pope does not claim to make an in-depth analysis of all the social reality that the Latin American society is divided into, but faces its suffering humanity and listens to the cry of the poor, sharing their passion in the light of the Gospel.

And in September there will be a trip to Cuba…

Carriquiry: John Paul II said, “The world should open to Cuba and Cuba should open to the world.” This is now being realized in a surprising way. Today we are grateful to the prophetic thrust of St. John Paul II. This offers very good chances for the visit of Pope Francis to continue on the path that led the two previous Popes to Cuba, but now in a particularly favorable historical situation.

In Latin America, we look at this journey with special interest because the re-establishment of relations between Cuba and the United States suggests the ability to deeply rethink and relaunch in new conditions a respectful and positive relationship of solidarity between the United States and all the countries of Latin America.

But before any political or diplomatic relationship, which Pope Francis thinks of always within a pastoral framework, the journey will take place to draw close to the Cuban people, to value all that the Church in Cuba has done and lived during so many difficult decades, to confirm the faith and encourage the Church to be increasingly present in her mission of evangelization and solidarity.

The Pope’s Vision

—John L. Allen Jr., cruxnow.org

Perhaps the most intriguing element of the Pope’s visit to Ecuador, Bolivia, and Paraguay was the suggestion that there’s an honest-to-God political strategy underneath his populist rhetoric.

It came in several allusions to the idea of a Latin American patria grande, or “great homeland.” Drawn from the thinking of 19th century founders of modern Latin America, such as Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín, the term today generally refers to the press for tighter economic and political unity across the continent.

But Francis, who has long been on record in favor of making the idea of a patria grande in Latin America a reality, since well before he was elected Pope, appears to mean something more by the phrase than that. He thinks Latin America, together, can and should be a counter-weight to some of the corrosive economic forces he sees at work in the world.

The South, in other words, has much to teach the long-dominant North.

Such a point of view is nothing new to Francis.

In 2005, then-Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina wrote a foreword to a book by a Vatican official from Uruguay named Guzmán Carriquiry, in which the future pontiff argued that Latin America has a pivotal role to play in the major ideological battles of the early 21st century.

Drawing on Argentina’s Peronist heritage, Bergoglio said that Latin America can lead the way towards a “third position” between Communism and free-market capitalism. In so doing, he said, Latin America can help resist an “imperial concept of globalization” he associated with the Anglo-Saxon world — presumably meaning, above all, the United States.

To accomplish that, he insisted that Latin American nations must form a more-or-less united bloc in global affairs.

“Alone and separated, we have very little chance and aren’t going anywhere,” he wrote a decade ago. “We’ll reach an impasse that would condemn us to being marginal figures, impoverished and dependent upon the major world powers.”

For all intents and purposes, what Bergoglio seemed to have in mind was a sort of EU for Latin America, an interlinked system of trade and political accords that would allow the continent to position itself as a serious counterpart to both the major Western powers and other global protagonists such as Russia and China…

To put the point differently, the late St. John Paul II focused on Poland in his effort to confront the Soviet empire, because as history’s first Polish Pope, he enjoyed unique political capital. In a similar way, history’s first Latin American pontiff seems to feel he has the best opportunity to galvanize his own continent against what he sees as the failures of global capitalism…

Facebook Comments