Anna Foa.

Studies in recent years have been bringing ever more to light the general role of protection that the Church played toward the Jews during the Nazi occupation of Italy, from Florence, with Cardinal Dalla Costa proclaimed Righteous in 2012, to Genoa, with Fr. Francesco Repetto, also Righteous, to Milan with Cardinal Schuster, and so on naturally to Rome, where the presence of the Vatican, as well as the existence of the extraterritorial zones, made it possible to save thousands of Jews.

Precisely with regard to Rome, the ways in which the work of sheltering and rescuing the persecuted was carried forward were such that they could not have been simply the fruit of initiatives from below, but were clearly coordinated as well as permitted by the leadership of the Church.

This erases the image proposed in the 1960s of a Pope Pius XII indifferent to the fate of Jews or even an accomplice of the Nazis.

I would like to emphasize here that this more recent image of the aid given to Jews by the Church arises not from pro-Catholic ideological positions, but above all from thorough research into the lives of Jews during the occupation, from the reconstruction of the stories of families or individuals. From field work, in short.

Refuge in the churches and convents emerges continually in the accounts of the survivors, runs as a common thread through the oral testimonies collected over the years in Italy — like the extremely vast body of testimonies of Italian Jews given to the Shoah Foundation — and is present in most contemporary memoirs.

It is recounted as a matter of fact; it belongs to the field of evidence, with all the differences of situations, from the convents that asked for room and board to those that welcomed Jews for free, who in turn gave a hand in the daily work, as in the case of the Jewish girls who helped to teach the children at the school of the Maestre Pie Filippini in Roma Ostiense, a case recounted by Rosa Di Veroli.

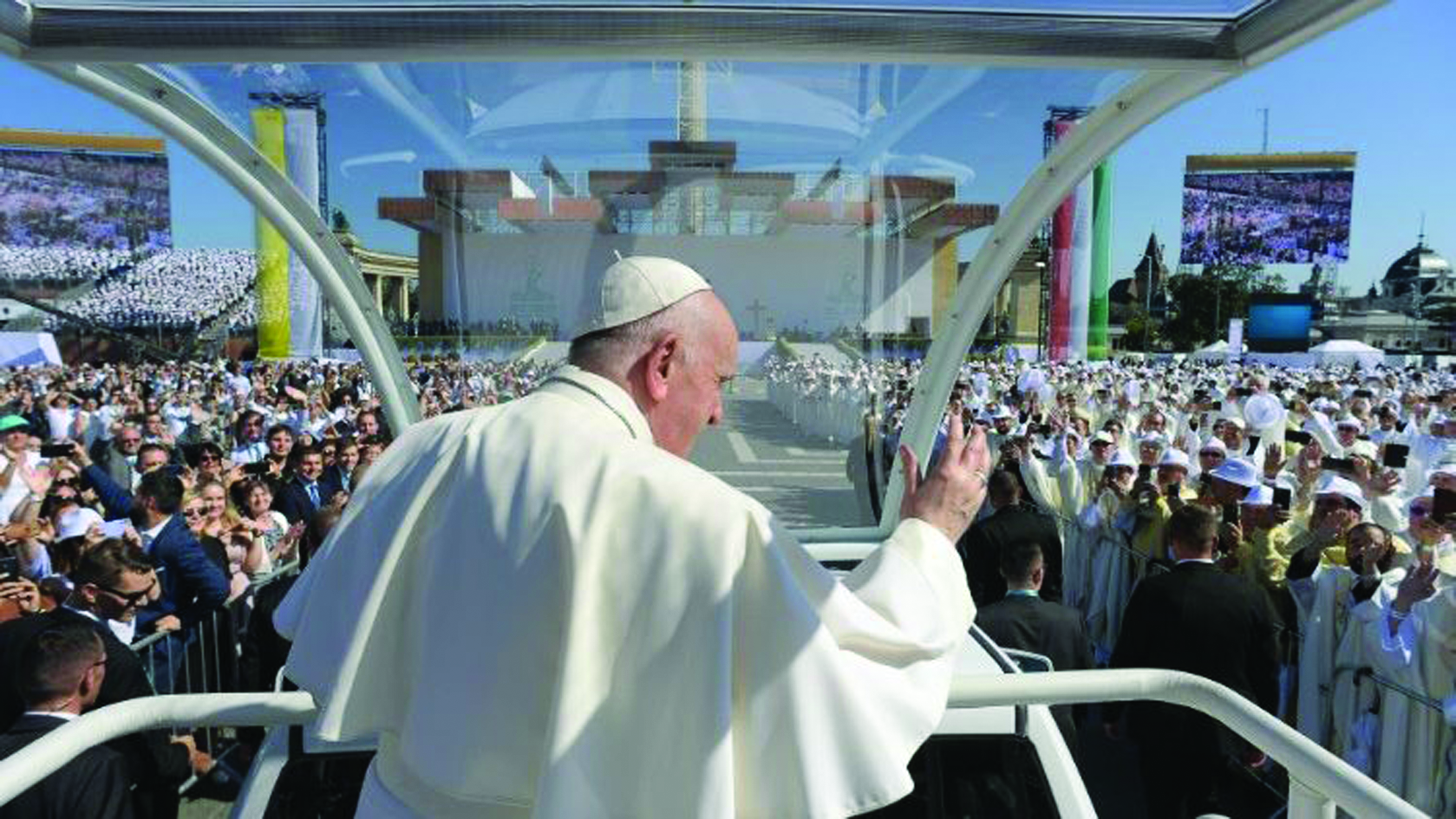

Jewish men, women and children received protection and care from the Catholic Church during the Holocaust.

It is, in short, an image that is the result not of the debate over the issue of Church and Shoah but also and above all of research aimed at illuminating the life and journey of Jews under the Nazi occupation.

The contested historiographical “quaestio” (question) on Pius XII and the Jews has hindered research for many decades and has pushed onto the ideological terrain every effort to clarify the historical facts. I think instead that, in order to write the history of the relationship between the Church and the Jews in occupied Italy, it is necessary in the first place to clear the field of this question.

The main question, that is, cannot be that of the relationship between the prophetic spirit of one Pope and the diplomatic compromises of another Pope, but that of how much and to what extent and also with how much internal opposition the Church and the Pope were in charge of the work of rescuing Italian Jews. The two questions are distinct and must, I believe, must be kept distinct.

The investigation into the concrete modalities of aid for the Jews, into the presence of Jews in the convents and churches, into the lives of Jews within ecclesiastical shelters, is beginning to bring to light an aspect to which, it seems to me, little reflection has been given so far, that of the change of mentality that can be traced back to it.

It is true that Jews and Christians had lived together for centuries, around the walls of the ghettos and in the ancient Jewish quarters, in Italy and particularly in Rome, but this coexistence rarely involved Churchmen. Now, out of necessity, because of the urgency of the persecution, priests and Jews shared the same food. Jewish women strolled down the hallways of the cloistered convents; Jewish men learned the Our Father and wore the habit as a precaution in case of German or fascist raids. Rosa Di Veroli, asked to pray together with the others in church, did so by reciting the Shemà Israel under her breath.

Was there on the Christian side any actual hope of touching the hardened hearts of Jews and impelling them to baptism? And those Jews who were baptized, did they do so out of true desire or through the fascination of a world that they did not know and which was offering them protection? There comes to mind the Lia Levi of Una bambina e basta, who for a brief moment was attracted to baptism.

We are obviously speaking of the cases of conversion in the convents, not of those conversions, real or simulated as they were, made in 1938 in the hope of avoiding the rigors of the racist laws, when in Milan Cardinal Schuster baptized Jews in the cathedral at dawn, and the most radical anti-Semitic newspapers saw in these baptisms “the Trojan horse of Jews in Arian and Christian society.”

All of this certainly set into motion, on both sides,hesitation and fear with regard to such a close daily relationship.

In the priests and above all in the sisters, these fears could be channeled into the impulse toward conversion, incorporating them into a more established and traditional relationship. In this way, daily life and attentiveness could find justification and support in the hope of leading a Jew to baptism.

Among the Jews, instead, the ancestral fear of being driven toward conversion sometimes led (cases of this kind emerge in the oral documentation) to a complete refusal to consider the idea of taking refuge in an ecclesiastical institution.

But it could also happen that none of this would come about. What is there to say, in Rome, about the Church of San Benedetto al Gazometro, where many Jews found refuge, and about its very young pastor at the time, Fr. Giovanni Gregorini, who found the time every day to chat with one of the Jewish refugees, a man of a certain age and very religious, speaking with him about their respective religions and their relations? Here, on the two sides, there was mutual respect and curiosity about the other.

In short, I believe that this new and sudden familiarity, brought about by the circumstances and without preparation, in conditions in which one of the two sides was hunted and in danger of its life and therefore in need of greater “Christian charity,” was not without consequences for the opening and reception of dialogue. A dialogue that would arrive much later, of course, and begin above all on a theoretical level, while this appears to us as a dialogue from below, made out of meals eaten together and conversations without pretenses, in part to overcome the anxieties of a relationship unknown until that moment.

In this way, the sisters of another Roman convent would add lard (note: which Jews could not eat) to the common soup only after having distributed it to the Jewish refugees among them. This too is a form of dialogue from below, it seems to me. Immediately after the war, at a time when the repression of the Shoah prevailed, this process of dialogue was partially blocked, on the one hand because the Jews were intent on rebuilding their world and identity after the catastrophe, and on the other because the Catholics seemed to have returned to the traditional positions in which the hope of conversion was stronger than respect.

It is perhaps this closing of the first years after the Shoah that impeded the development of that dialogue from below, on a par with that at the higher levels, as demonstrated by the failed encounter of Jules Isaac with Pius XII.

Whatever may have been the case, in the early 1960s with The Deputy by Rolf Hochhuth, this process would be overshadowed by the “black legend” of Pius XII, with the result of hindering and obfuscating the memory and impact of that first shared journey.

Now is the right time to start examining it again.

Facebook Comments