Fr. Soria is a monk in the abbey of the Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen (Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos), a Solesmes foundation near the Spanish capital, and his thesis was defended and approved at the Faculty of Canon Law of the University of San Dámaso, the main house for the formation of priests and theologians owned by the Archdiocese of Madrid, on May 29, 2013. The thesis was published just recently by Spanish publisher “Ediciones Cristiandad” under the title “The Principles of Interpretation of the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum” (“Los principios de interpretación del motu proprio Summorum Pontificum”), which is why the Cardinal’s text has only now become available.

Cardinal Cañizares’ preface is a long presentation of the book, and it obviously includes many references to the work itself – but what makes it particularly special is the depth of the Cardinal’s appreciation for the motu proprio, and his defense (which had always been defended by those of us deeply appreciative of the nature of Summorum Pontificum) that what the motu proprio established in law was nothing less than the juridical equality of both forms of the Roman Rite. It is a groundbreaking text. Here below is a translation of the most important excerpts of the Spanish original.

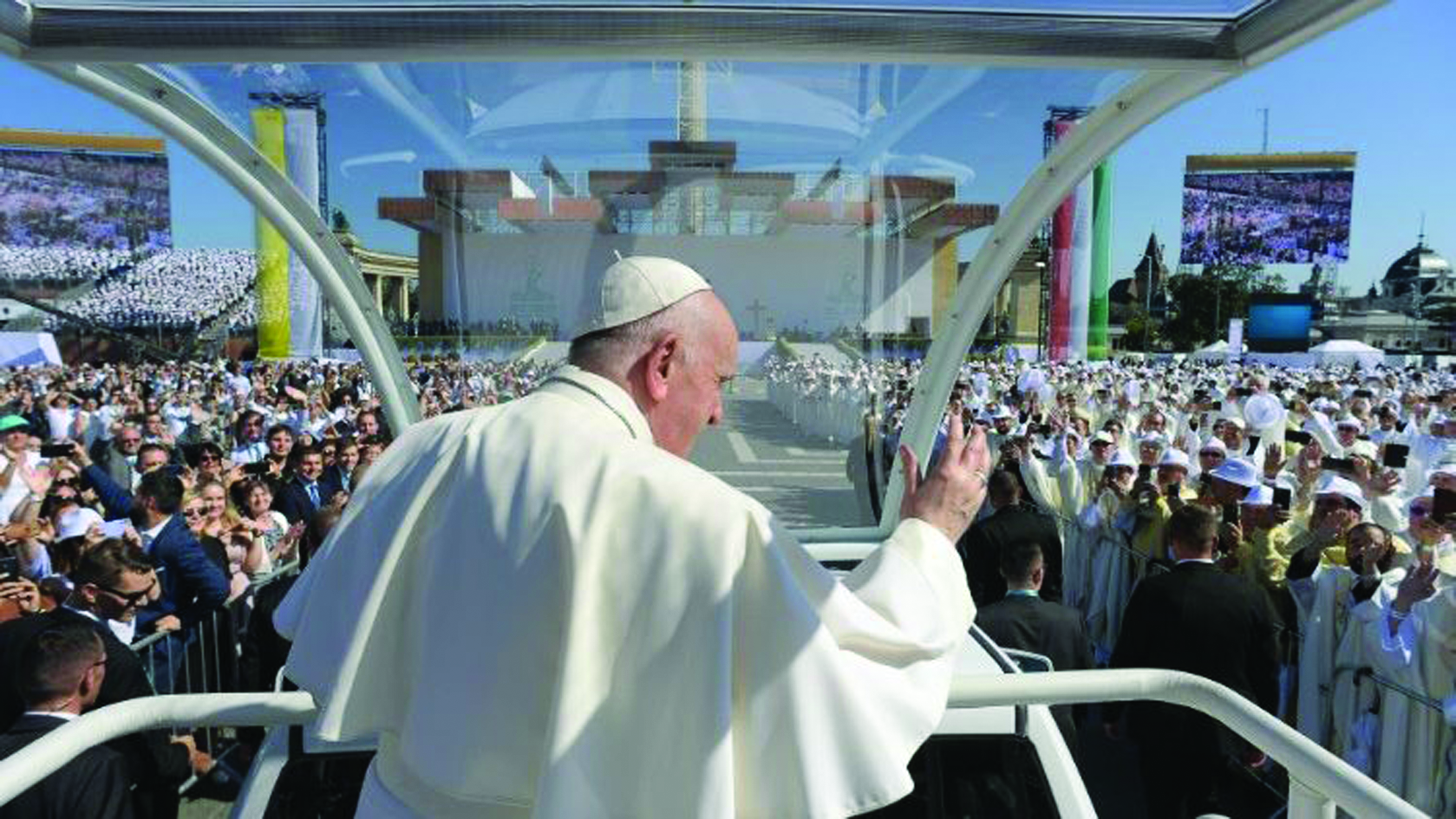

Cardinal Antonio Cañizares Llovera during a celebration of Holy Mass in the Tridentine rite in St. Peter’s Basilica on November 3, 2012.

Preface of Cardinal Cañizares Llovera to the Doctoral Thesis of Fr. Alberto Soria Jiménez, O.S.B.

We find ourselves before a work that tackles, scientifically, a theme that in the past few years has been the object of heated controversies. Nevertheless, from its very beginning two characteristics of this work must be considered: its academic character and the belonging of the author to a community that is faithful to the great principles of the liturgy, but in which the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite is not celebrated. This has allowed him to observe the situation “from the outside,” rendering possible the great objectivity reflected in his research.

The conception, clearly present both in the motu proprio and in the documents related to it, that the inherited liturgy is a wealth to be preserved, is to be understood in the spirit of the liturgical movement in the line of Romano Guardini, to which Benedict XVI owed so much of his personal relationship with the liturgy since his youth. The detailed and documented history of the process, from its beginnings in the 1970s up until today, that the author of this work presents to us, shows how this legislation was not the momentary result of pressure, nor a reflection of the personal and isolated opinion of the Pope, but rather that other persons had long wished for a similar solution. These criteria of the young priest Joseph Ratzinger were consolidated and purified throughout the years, and were taken up by John Paul II, who had considered the possibility of providing appropriate legislation.

The mood among the cardinals designated to reflect upon this theme [in 1986] was favorable. The cardinalatial commission established by John Paul II, in which the influence of Cardinal Ratzinger was undeniable, had proposed to, “eliminate the impression that each missal is the temporal product of each historic epoch,” and had affirmed that, “liturgical norms, not being truly and properly ‘laws,’ cannot be abrogated, but subrogated: the preceding ones in the subsequent ones.”

The demonstration that is very important, and present in this investigation, is that the attitude of Benedict XVI is not so much a novelty or a change of direction, but rather an accomplishment of what John Paul II had already undertook — with initiatives such as the consultation of the cardinalatial commission, the motu proprio Ecclesia Dei, and the creation of the Pontifical Commission of the same name, the mass of Cardinal Castrillón Hoyos in Santa Maria Maggiore in 2003, or the declarations of the pope to the Congregation for Divine Worship that same year.

The history of the process reveals that, from the beginning, the wish to preserve the traditional form of the mass was not limited to integrists, but that people of the world of culture or writers, such as Agatha Christie and Jorge Luis Borges, signed a letter demanding its preservation, and that Saint Josemaría Escrivá made use of a personal indult granted spontaneously by Archbishop Bugnini himself. It is also to be noted the concern of Benedict XVI to emphasize that the Church does not discard her past: by declaring that the Missal of 1962, “was never juridically abrogated,” he made manifest the coherence that the Church wishes to maintain.

In effect, she cannot allow herself to disregard, forget, or renounce the treasures and rich heritage of the tradition of the Roman Rite, because the historical heritage of the liturgy of the Church cannot be abandoned, nor can everything be established ex novo without the amputation of fundamental parts of the same Church.

Another important aspect comes from the reading of the historical narrative in this work: the advances that have taken place throughout these years regarding the pastoral sensibility for these faithful, the greater attention to their persons and to their spiritual welfare. In effect, the legislation was at first [Rorate note: “Agatha Christie” Indult, personal indults, Quattuor abhinc annos, Ecclesia Dei adflicta] very limited, it took into account only the clerical world and it practically ignored the lay faithful, considering that the first concern was disciplinarian: to control the potential disobedience to the newly promulgated legislation. With time, the situation took on a more pastoral aspect, in order to meet the needs of these faithful, which ends up being reflected in the strong change of tone of the terminology being used: it is thus that the “problem” of the priests and faithful who remained attached to the so-called Tridentine rite is not mentioned anymore, but rather the “wealth” that its preservation represents.

What was thus created was a situation that was analogous to the one that had been normal for so many centuries, because we must recall that Saint Pius V had not forbidden the use of the liturgical traditions that were at least 200 years old. Many religious orders and dioceses therefore preserved their own rite; as Archbishop of Toledo, I was able to live this reality with the Mozarabic Rite.

The motu proprio modified the recent situation, by making clear that the celebration of the extraordinary form should be normal, eliminating every restriction [todo condicionamiento] related to the number of interested faithful, and not setting up other conditions for the participation in said celebration than the ones normally required for any public celebration of the mass, which allowed for a wide access to this heritage that, while it is by law a spiritual patrimony of all the faithful, is, in fact, ignored by a great part of them. In effect, the current restrictions to the celebration in the extraordinary form are not different from those in place for any other celebration, in whatever rite.

Those who wish to see, in the distinction made by the motu proprio of cum and sine populo, a restriction to the extraordinary form forget that, with the missal promulgated by Paul VI, the celebration cum populo without the authorization and agreement by the parish priest or rector of the church is not allowed either.

The views of the young Father Joseph Ratzinger on the liturgy were developed over the years, and in his papacy.

On the other hand, the possibility, expressly contemplated in the motu proprio, that in the celebration sine populo the spontaneous presence of faithful be admitted without obstacles (an expression that had provoked more than one ironic remark by the critics of the document) simply allowed for the end of the strange circumstances by which, though celebrated by a priest in a completely regular canonical situation, this Mass remained closed to the participation of the faithful simply because of the ritual form being used, a form that was on the other hand fully recognized by the Church. The situation of the 1970s — in which priests who could not adopt the new missal for reasons of health, age, etc, were condemned to never again celebrating the Eucharist with a community, as small as it could be — was also prevented, which would be seen, according to the current sensibility, as discriminatory.

On the other hand, to deliberately restrict the Mass cum populo, limiting in practice the celebration of the extraordinary form sine populo, would contradict the words and intentions of the conciliar constitution: “… whenever rites … make provision for communal celebration involving the presence and active participation of the faithful, this way of celebrating them is to be preferred, so far as possible, to a celebration that is individual and quasi-private.” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 27)

Facebook Comments