Perhaps Pope Benedict, making some remarks during his most recent speech to the Roman Curia, recalls the letter he wrote.

“Dear Baby Jesus, soon you will descend on earth. You will bring joy to children, and I will be joyful, too.” This is the beginning of a Christmas letter written in 1934 by a 7-year-old child in Germany. It was written in Sütterlinschrift, a typical italic handwriting of that time. The author was Joseph Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI.

What did the Pope wish for when he was 7 years old? “I would like the Volks-Schott, a green suit to celebrate Holy Mass, and a Jesus’ Heart,” he wrote. “I will always be good. Best regards, Joseph Ratzinger.”

The letter was so unusual that Maria Ratzinger — the Pope’s older sister, who took care of him until her death in 1991 — decided to keep it. The letter was found when Ratzinger’s house in Pentling, near Regensburg, was being restored. The house is now a museum, inaugurated at the end of last summer by Monsignor Georg Gänswein, then Benedict XVI’s private secretary. (Gänswein reported that the rediscovery of the childhood letter “made the Pope very happy, and made him smile.”)

What is most striking is that little Joseph does not ask for toys or sweets. He asks for the Schott, a book containing the breviary and a missal, with all the readings for Mass (with text in Latin also). At that time, two editions were available in Germany: one for children and one for adults. Little Joseph, through reading that book, began to love the liturgy that was so central to his family’s life.

Little Joseph then asks for a vestment to celebrate Mass. No surprise — the Ratzinger brothers used to pretend to be “parish priests,” and their mother made vestments for them. “We pretended to celebrate Mass and we had vestments made for us by our mother’s seamstress,” Georg Ratzinger, the Pope’s brother, told Inside the Vatican. “By turns, one of us was the priest and the other the altar boy.” Finally, little Joseph asked for a “Jesus’ Heart,” that is, an image of the Sacred Heart, to which his family was very devoted.

This childhood letter is more than just an amusing anecdote. It is a window into the Pope’s mind. One should perhaps keep this letter in mind when one listens to Benedict XVI’s speeches. Whenever he defends the family, there seems to be something drawn from his memories of his own family — that it was a happy family, in which life’s rhythms were set according to the liturgy, that it was a family where all rejoiced with one another, that it was a family in which it was reasonable to live, because the family was the best context for a child’s growth.

When he became a theologian, Joseph Ratzinger expanded his reflection on the meaning of the family, based on the Holy Family of Nazareth. Through the example of the Holy Family, he tried to explain why a “traditional” family is needed. This defense of the family started on a strictly theological basis. But there was also this experiential basis.

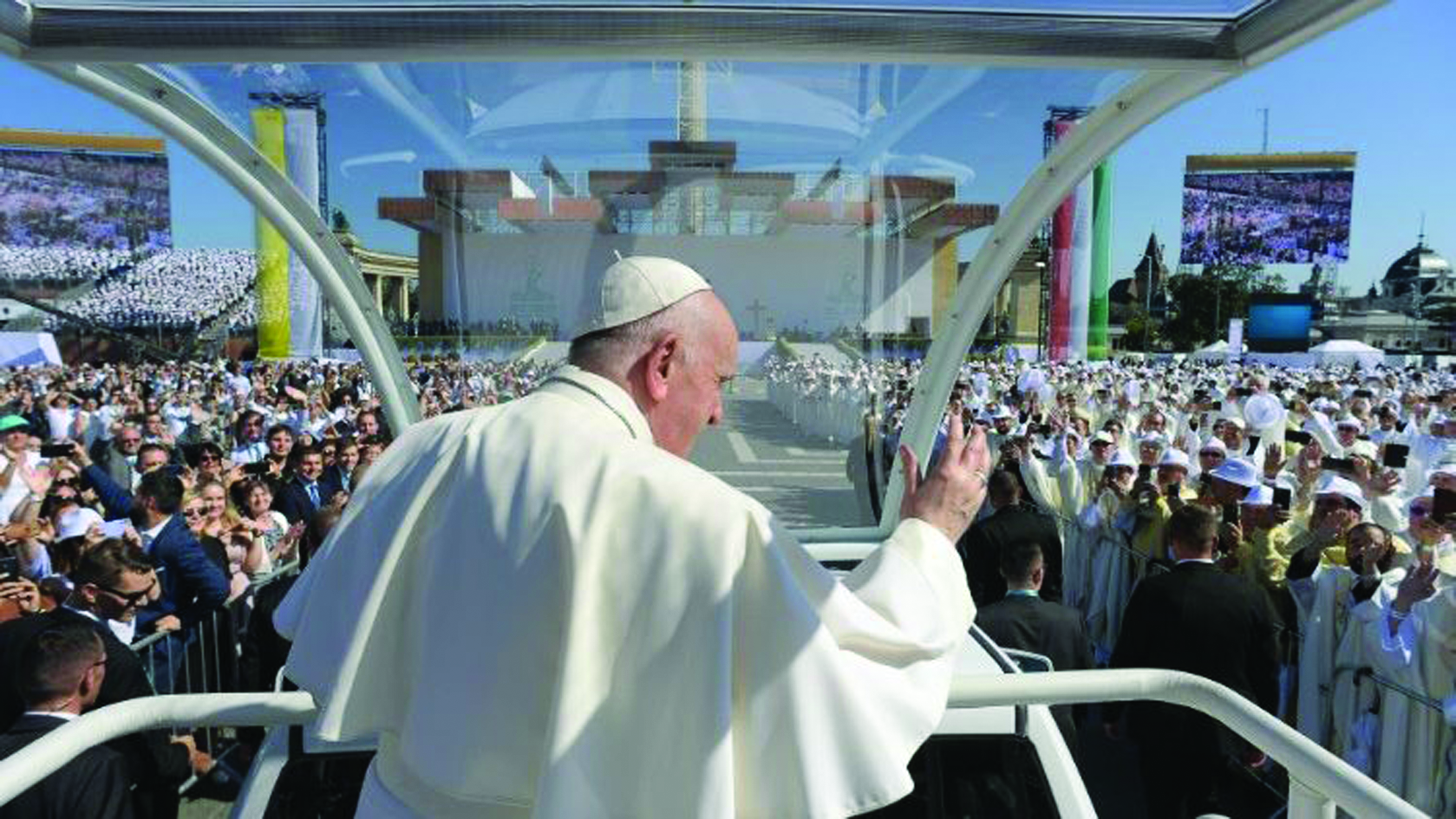

The Pope put this idea of the family front and center in his Christmas address to the Roman Curia in December. Each year, the Pope uses the address to the Curia to look back at the year coming to an end. But as usual, this year the Pope took the high road. There was no hint of “Vatileaks,” nor of internal Church problems. In the end, he seemed to be saying, these problems really do not amount to much; they are just ordinary miseries of the human condition when compared to the great challenges facing the Church. Rather, Benedict XVI focused on three issues that marked the Church’s life and that will be on the agenda for many years to come: the family, religious dialogue, and the new evangelization.

The Pope started with the family. He approached the topic by citing arguments recently made by the Chief Rabbi of France, Gilles Bernheim, in defense of the traditional family. Bernheim last year sent a 25-page letter to France’s President François Hollande to explain all the reasons why he and his community are against “marriages for all.” The Pope then noted that before now, the family has been in crisis due to a misconception of freedom, but today, the very idea of man is in crisis. This crisis has a specific name: the new theory of gender.

Joseph Ratzinger when he was five years old

In this theory, gender is seen as a choice for men and women, not something given by nature. This theory of a shifting, volitional gender identity is behind much of the vocabulary of human rights promoted in United Nations documents and continuously denounced by Holy See officials.

Gender seen as something “chosen” means that, in our time, a human being is increasingly ready to call his or her own fundamental nature into question, the Pope said.

“The manipulation of nature, which we deplore today where our environment is concerned, now becomes man’s fundamental choice where he himself is concerned,” the Pope said. “Nowadays, there is only the abstract human being, who chooses for himself what his nature is to be.”

And this is a threat to the family, Benedict said. “When the freedom to be creative becomes the freedom to create oneself, then necessarily the Maker himself is denied and ultimately man too is stripped of his dignity as a creature of God, as the image of God at the core of his being,” the Pope said. “The defense of the family is about man himself. And it becomes clear that when God is denied, human dignity also disappears. Whoever defends God is defending man.”

Defending man is the Church’s mission. In the end, it is the same agenda of little Joseph. He asked for a Schott as a Christmas gift, a book of liturgies, to lock himself in step with Jesus, starting a long path in life that brought him to the papacy.

Facebook Comments