When Timothy M. Dolan was elected by the American bishops as their president in November 2010, only 18 months after Pope Benedict had transferred him from the archdiocese of Milwaukee to that of New York, it was seen by many as a rejection of the man who, according to precedent, was expected to be chosen: Bishop Gerald F. Kicanas of Tucson, then vice president of the Bishop’s Conference. In fact, Kicanas remains widely respected by his peers.

Dolan’s choice reflected the bishops’ conviction that, in Dolan, they had someone whom John Allen describes as “that rare figure who manages to put a warm human face on the Church’s public image.”

With the Church still reeling from the past failure of bishops to deal adequately with the sexual abuse of minors by clergy (a problem which afflicts every institution in society in regular contact with youth – but framed by the media as unique to Catholic priests), the opportunity to choose a leader who, in Allen’s words, “never saw a back that he didn’t want to slap,” was just too good to be passed up.

Allen’s book is the result of some 30 hours of on-the-record recorded conversations between him and Dolan. Originally reluctant to make himself available, lest he be considered ambitious, Dolan consulted Cardinal Justin Rigali, now archbishop emeritus of Philadelphia, who told Dolan that Allen was offering him an opportunity to evangelize by presenting the Church’s message in a manner not often available to Church leaders. Dolan has used the opportunity well.

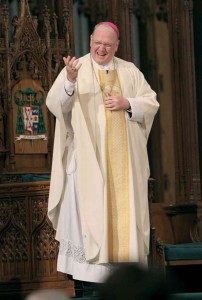

Cardinal-designate Timothy M. Dolan of New York addresses the news media at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York January 6. He was among 22 new cardinals

named that day by Pope Benedict XVI.

Allen’s contribution to the book is important. He does more than frame the questions. He gives valuable background and commentary which makes the conversation with Dolan come alive.

An example is his comparison of Dolan with the last two Popes. With John Paul II Dolan shares “a swashbuckling, daring, ‘man’s man’ personality; a lively sense of humor, an instinctive genius for communication, personal fearlessness, rooted in a rock-solid sense of who they are. Dolan is American the way John Paul was Polish.” On the surface the “backslapping extrovert” Dolan seems miles removed from the “shy and cerebral” Benedict XVI. Underneath, however, both men are deeply committed to what Allen calls “affirmative orthodoxy.” Both want to present the Church’s message in the most positive way possible, so that it comes across “as a yes rather than a no: the accent is on what the Church is for, rather than what it is against.”

Dolan does not shy away from difficult subjects. The sexual abuse scandals have been especially painful for him, he tells Allen, because he still has “an altar-boy notion of the priesthood. To this day, I think of myself as a priest, not as a bishop or archbishop, and there’s nothing else I ever wanted to be.”

To those who charge that the Church is anti-gay Dolan says: “It’s absurd to identify yourself with your sexual urges. … Whatever your sexual attraction is, I don’t really care too much about. I’m dealing with who you are and the way God sees you. If you see yourself as God sees you, well, you will act virtuously.” All the Church’s teaching on sexuality, Dolan insists, is intended not to fence people in but to point the way to a true happiness and fulfillment which will last a lifetime and extend into eternity.

Dolan says that five years ago, when he was archbishop of Milwaukee, he got far more questions about women’s ordination than he does now. A woman reporter in his former diocese wanted to know how he felt about this question. He would be happy to discuss his feelings, Dolan responded, provided his questioner understood that what he felt was unimportant: his job was to uphold Church teaching.

Cardinal-designate Timothy M. Dolan smiles as the assembly at Mass in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York January 6 applauds the announcement that he was named a cardinal by Pope Benedict XVI.

To charges that the Church is anti-women, Dolan points out that the Church’s vast charitable and educational work is almost entirely in female hands. When he visits New York’s Catholic Charities office, he doesn’t encounter bitter women asking, “Why can’t we be priests?” Instead he sees “women who put me to shame in the way they’ve digested the Gospel, and they’re happy to be part of the Church’s good work.” To critics who object that Church leadership, at least, is a boys’ club, Dolan counters: “I had a woman as chancellor, a great one, in Milwaukee, Barbara Ann Cusack.”

Dolan’s constant search for a “yes” rather than a “no” explains his rejection of public bans on reception of Communion for pro-choice Catholic politicians. He considers such punitive measures “counterproductive.” We can only win the abortion battle by changing hearts and minds, he says. Bishops who issue public edicts about receiving Communion cause pro-life activists to stand up and cheer. Unfortunately there are not enough of them to win the battle, he believes. For that, we need those in the middle, many of them still on the fence. We must never give the impression that abortion is “an intramural Catholic issue,” Dolan warns. “When we start talking in a disciplinary way, we have given aid and comfort to the enemy. It’s now a human rights issue, it’s a civil rights issue, it’s a social justice issue.” To the charge that this means forming an alliance with the Republican Party, Dolan counters: “Both parties have let us down.”

Recalling the failure of almost all U.S. bishops in the pre-Civil War era to condemn slavery (defended in the 1850s with arguments chillingly similar to those used by pro-choice people today), Dolan rejoices that, at least on the abortion question, there is no such timidity today. He pleads, however, for a more robust response to attacks on the Church which reflect ignorance and bigotry. A case in point is the widespread assumption that the Church is phenomenally wealthy, yet indifferent to people who are starving. “We need a resurrected sense of apologetics,” Dolan says — and offers an example: “When I see from Hollywood critics of the Church one millionth of a percent of the charity I see coming from the Catholic Church, maybe they’ll have a little bit of credibility with me when they badmouth the Catholic Church.”

On the personal level, Dolan describes how he prays, what the Mass means to him, and his experiences (some quite amusing) as an often anonymous penitent in the confessional. Especially encouraging to me were his stories of older priests who influenced him when he was just starting out. I knew a number of these men myself – and found them quite ordinary. Reading about how they had helped a young priest made me realize that one need not have exceptional gifts to exercise a strong influence for good.

Are you hopeful about the Church’s future, Allen asks toward the end of the book. Definitely, Dolan says, “because I look at the Church through the eyes of someone in love. Someone in love is always going to be hopeful.” One could hardly find a better example of the warm face which Timothy Dolan is always striving to put on the Church’s public image.

John Jay Hughes is a priest of Archbishop Dolan’s archdiocese of birth and ordination, St. Louis, and the author of the widely acclaimed memoir, No Ordinary Fool: A Testimony to Grace (Tate Publishing).

Facebook Comments