By Federico Lombardi

After his doctorate on St. Augustine, defended in 1953, came the goal of obtaining the license to teach. Here he experienced a difficult and almost dramatic passage in his life, due to the open clash between two influential professors of the Munich Faculty – Gottlieb Söhngen, his teacher, and Michael Schmaus – over his dissertation on St. Bonaventure. Eventually the work was accepted, and Ratzinger became a lecturer in 1957. But these tensions would leave a profound legacy. The young theologian, who until then had achieved mostly brilliant successes and high praise, had the novel experience of harsh criticism, to the point where his career was in great jeopardy. Wisely at the end he observed – regardless of the merit of the discussions – that “humiliations are necessary […]. It is good for a young man to know his limitations, to suffer criticism as well, to experience a negative phase.”

After his doctorate on St. Augustine, defended in 1953, came the goal of obtaining the license to teach. Here he experienced a difficult and almost dramatic passage in his life, due to the open clash between two influential professors of the Munich Faculty – Gottlieb Söhngen, his teacher, and Michael Schmaus – over his dissertation on St. Bonaventure. Eventually the work was accepted, and Ratzinger became a lecturer in 1957. But these tensions would leave a profound legacy. The young theologian, who until then had achieved mostly brilliant successes and high praise, had the novel experience of harsh criticism, to the point where his career was in great jeopardy. Wisely at the end he observed – regardless of the merit of the discussions – that “humiliations are necessary […]. It is good for a young man to know his limitations, to suffer criticism as well, to experience a negative phase.”

Thus Ratzinger became a professor. This was a key stage in his life, which lasted almost two decades. After all, it was a time in which he did what he felt called to and what he wanted to do. Yet it was a stage that also saw multiple phases. After teaching Dogma and Fundamental Theology at the high school in Freising, the first chair to which he was appointed was that of Fundamental Theology at the University of Bonn, where he remained from 1959 to 1963; then he moved to Münster for Dogmatic Theology (1963-66), then to Tübingen (1966-69), and finally to Regensburg (1969-77). Accounts of the exceptional quality of his university teaching, such as depth of content, clarity of exposition, care and finesse of language, are unanimous. Students thronged the lecture halls to listen to him. We were able to echo and enjoy these qualities on a broader and more universal level, reading the documents and listening to the speeches, catecheses and homilies of the professor who became Pope.

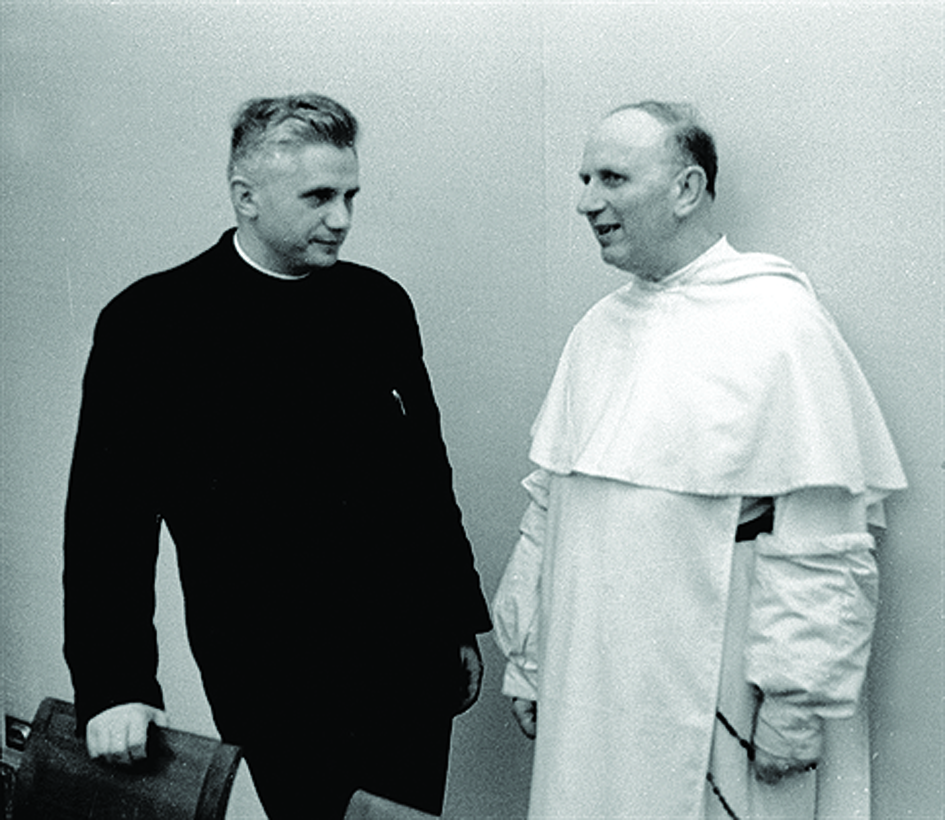

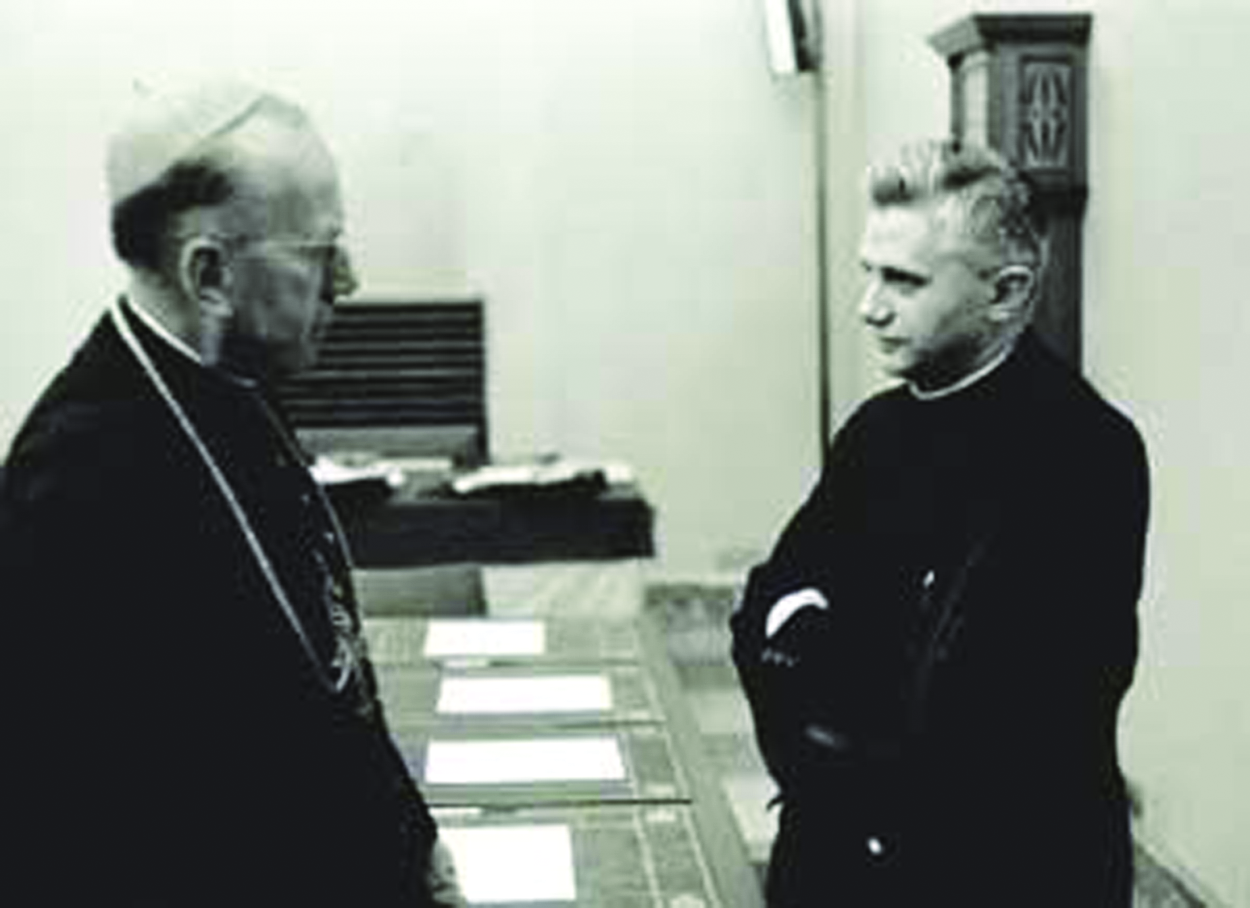

Vatican II, October 1962-December 1965. Here Joseph Ratzinger participated as expert theologian for the elderly Cardinal of Cologne, Joseph Frings. Below, during breaks in conversation with the French cardinal and theologian, Dominican Yves Marie-Joseph Congar, and with the Austrian Cardinal Franz König, a scholar of considerable fame

A crucial event in Ratzinger’s life occurred during this period: his participation in the Second Vatican Council as an expert theologian for the elderly Cardinal of Cologne, Joseph Frings.

When the Council was announced, Ratzinger was teaching in Bonn, in the Cologne diocese, and soon made his mark with an important lecture on the theology of the Council, which he attended.

There was a spark. Frings, though nearly blind, would be a leading figure in Vatican II, a leading figure in the episcopates of central and northern Europe — France, Germany, and Belgium — who would exercise a decisive role in conciliar thought.

Ratzinger, in his early 30s, trained in an academic environment different from that of the Roman faculties, accompanied Frings and prepared notes for him, and wrote drafts of interventions that would leave their mark.

Students thronged the lecture halls to hear him; then came his participation in Vatican Council II

In addition to his contribution to the formulation of the documents, his stay in Rome during the Council sessions represented a unique opportunity for the young professor to get to know and enter into personal dialogue with the leading theologians of the day — Rahner, de Lubac, Congar, Chenu, Daniélou, and Philips — and experience deeply the universality of the Church and the challenges of today’s world, experiencing from the inside the greatest ecclesial event of the century. His horizons widened to the ends of the world; his theological and pastoral reflection engaged with crucial questions, and he could never again close himself off within limited or short-sighted perspectives.

Not everything, however, was easy and trouble-free. The frequent changes of university positions are an indication of this. The exciting and creative time of the Council was also followed by negative developments and divisions in ecclesial and theological fields. The debate over the role of the theologian in the Church became heated, particularly in Germany.

Thus, while it was Hans Küng himself who had invited Ratzinger to move to Tübingen, the paths of these two theologians diverged and they would become inexorably estranged.

At a certain point Ratzinger had to take note that for Küng and others “theology was no longer the interpretation of the faith of the Catholic Church, but established itself as it could and should be. And for a Catholic theologian, such as I was, this was not compatible with theology.”

In this context, coinciding with the student unrest of 1968 that deeply disturbed university life, Ratzinger left Tübingen for the quieter Regensburg. But one should not think that those years were not also intense and fruitful.

That same year of 1968 saw the publication of his most-read book, Introduction to Christianity.

Facebook Comments