By Priscilla Smith McCaffrey

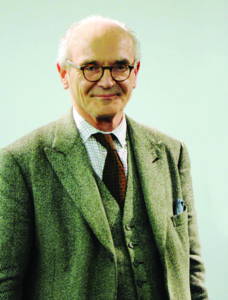

Martin Mosebach, now 70, is an award-winning German Catholic novelist and essayist who has traveled repeatedly in China and has a great love of religious tradition and culture. Author Priscilla Smith McCaffrey asked Mr. Mosebach for his thoughts on the state of the Catholic Church in China.

Martin Mosebach: My few and short trips to China and visits with some of the congregations in Shanghai, Nanjing, and Beijing posed more questions than answers—only someone deeply knowledgeable would be able to give a satisfactory answer. Shanghai is probably one of the more prominent sites of the Catholic Church in China, which is only, or mostly, represented by the “Patriotic Church.” There, I assisted a celebration of the Ancient Mass singing the Ordinarium in a somewhat dilapidated neo-Gothic church in the former French Convention.

Martin Mosebach: My few and short trips to China and visits with some of the congregations in Shanghai, Nanjing, and Beijing posed more questions than answers—only someone deeply knowledgeable would be able to give a satisfactory answer. Shanghai is probably one of the more prominent sites of the Catholic Church in China, which is only, or mostly, represented by the “Patriotic Church.” There, I assisted a celebration of the Ancient Mass singing the Ordinarium in a somewhat dilapidated neo-Gothic church in the former French Convention.

The priest wore a kind of Chinese, traditionally-stylized priest’s garment of white silk. After Mass, I gave a lecture on “Heresy of Formlessness” to approximately thirty parish members. During Mass, many prayed the Rosary. It was a solemn, intensive atmosphere. Later, the priest showed me his Missale, wherein the pro Papa nostro had been deleted by the Authorities whilst he assured me: “This is the place where we pray for the Pope since we know that we cannot stay Catholic without him.” Most of the bishops and priests kept it that way, notwithstanding the fact that some of them were Communists, though probably few.

In the Shanghai cathedral, again neo-Gothic, the Chinese translation of the Latin Ordinarium was displayed on huge electronic screens.

The Shanghai diocese, by the way, is suffering from the fact that [in 2012] the newly-consecrated bishop announced directly after his inauguration ceremony he would leave the Patriotic Association, the result being that he was punished with a house-arrest still going on today. So the diocese is without leadership at present.

In Beijing, in the center of political power, the underground church prevails, surprisingly enough. Here we cannot say it is catacomb-like, but rather has huge neo-Gothic churches frequented by plenty of people. It might be compared with the situation during the Roman Empire, when there existed longer periods of less acrimonious persecutions and with official parish structures and building activities. But since everything, as a rule, in China is [subject to scrutiny or perhaps] forbidden, the Chinese State may interfere anytime and destroy everything in an instant.

Do some of the lay people believe it is possible to be a good patriot as well as a faithful Christian?

MM: We enjoyed a friendly contact with a musician, now Catholic, and her family; very cultivated people in the sense of being rooted in the ancient Chinese culture—but simultaneously fervent patriots who only wished to see an agreement between the Chinese state and the Church. Many people, not at all Communist, are of a firm belief that Mao, and no less Chiang Kai-Sheck by the way, led China out of its colonial disgrace and misery. Impressive to most is also the unprecedented economic surge over the last decades. The young have little memory of the past poverty, which gave way to a prosperity of the many, comparable to the West’s. In such social circles it is appealing to be a pious Catholic and simultaneously part of the Chinese Patriotic Church.

They do not see this as problematic?

MM: In itself it is a contradiction and gives you an uneasy feeling they cannot really grasp. Let’s keep their history in mind: since the age of colonialism, any influence by a strange power—even the Pope’s—has been regarded as intolerable. We can come up with no suggestion as to how to escape this situation—great creativity is needed.

Probably there is a unique solution…

MM: In our imaginations one way might be considered: the erection of a Chinese patriarchate, promoted by the Holy See, might present a legitimate tradeoff, at least a chance of working.

Does the Church in China follow cultural leads from the Church in the West?

MM: An important point to make is that the schismatic — or better said, not quite schismatic — Patriotic Church gives the impression of not being heretical! Rather, they seem to live up to better doctrinal standards than most of the Western countries with respect to faith, sacraments, and theology.

That’s actually a stunning declaration. I have a Chinese traditionalist acquaintance who points out that the rift between supporters of old and new liturgy is a result of Western history and politics. Perhaps the Church in the West has much to learn from the faithful of the East?

MM: The situation of the Catholic Church in China has to be compared with the one in the Soviet Union. Their faith and liturgy were truly orthodox whilst the high clergy was full of KGB agents.

But this mere fact enabled the Church to survive, and after the downfall of the Soviet system made it possible for the Church to be transformed and enter a new fruitful era. It ought to be mentioned, though, that a detestable bishop could denounce his parish to the secret police.

And what do the troops on the ground say? Is there any freedom to even speculate?

MM: What Cardinal Zen would say to the propositions above, I cannot tell. You may imagine that I wouldn’t dare to contradict this great and admirable man. Cardinal Zen, in his heart, of course refers to the great fighters who were prepared to go to prison for twenty or thirty years in order to testify to the papacy. You can only love these people, and find their submission tragically heroic in the face of the papacy of today. To put it briefly, my guess is that the Church of China is far more complex than, say, the Egyptian Coptic Church. I can say no more to this subject.

Facebook Comments