Personal reflections from a seasoned Catholic journalist

By Tom Hoopes

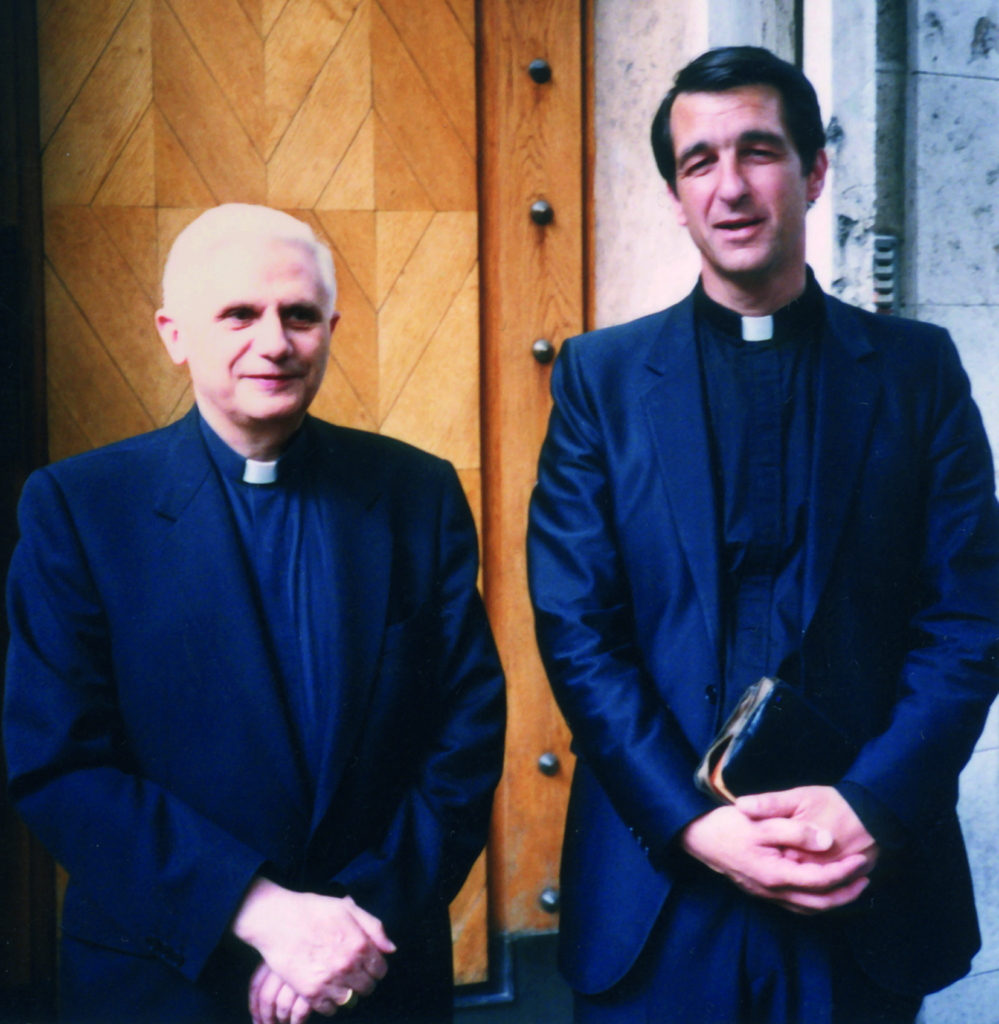

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger is pictured with Jesuit Fr. Joseph Fessio in this 1987 photo. The then 46-year-old priest is the founder and editor-in-chief of Ignatius Press, which has published 25 books in English by Cardinal Ratzinger (CNS photo courtesy Ignatius Press/Dorothy Peterson)

The image I will always have of Pope Benedict XVI is encountering him in St. Peter’s Square one early morning in the Jubilee Year 2000. I was the executive editor of the National Catholic Register, covering the Holy Year. He was Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the prefect for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. He smiled at me from a distance. I smiled back. Now was my chance. I fished my pen and notepad out of my pocket and strode confidently toward him — but I’ll finish that story in a moment.

A New Aquinas

It’s hard to believe that was 23 years ago, and that now he’s dead. A few days after his death, I told the story of my encounter with him at a special presentation in a windowless room under St. Benedict’s Parish Elementary School cafeteria in Atchison, Kansas.

Our pastor had realized that he had something worldclass to offer his parishioners: Benedictine College theologian Dr. Matthew Ramage is a parishioner and a highly respected theologian whose academic work has been dedicated to examining and elucidating the remarkable breadth and depth of Benedict XVI.

Ramage called Benedict a new Thomas Aquinas and a 21st-century Doctor of the Church.

He described how, as a theologian, Ratzinger would pack lecture halls in Regensburg with students eager to hear the shy man read quietly from a prepared lecture, his glasses at the end of his nose. Later, book-length interviews with Ratzinger on wide-ranging topics were newsmakers whenever they appeared.

“Benedict is like Aquinas because he is always finding ways to enrich the ancient tradition by new discoveries,” he said.

Then Ramage told the fascinating story of how Benedict’s career put this remarkable mind in the center of Catholic officialdom at the highest levels for decades.

In his early 30s, Ratzinger became a theological consultant for the Second Vatican Council. This means not only that he knows the Council backwards and forwards, but that his presence is felt, to a degree, in the shape of the documents themselves.

The year he turned 50, Ratzinger was made a cardinal by Pope John Paul II. Four years and two popes later, he was made prefect of the Congregation of the Faith. This made him the rock of calm at the center of the storm of dissent and doubt that swirled through the Church as Vatican II was implemented – or not implemented, as the case may be.

In 2002, three days after turning 75, Cardinal Ratzinger gave a remarkable homily to cardinals gathering in conclave — and was punished for his good deed by being made Pope. He put the Corbinian bear on his coat of arms, identifying himself with the animal that was forced to make a trip to Rome, carrying a saint’s baggage.

Ramage painted a picture of Ratzinger as the quintessential behind-the-scenes leader, a theologian who spent his career not in the spotlight, but just outside it — not directing the play, but making the whole show work right.

He Saved My Soul

This is what Pope Benedict XVI did for my personal life, too.

I lost my faith around the age of 10 which, recent statistics suggest, is about when most kids lose their faith nowadays. The Church didn’t help. Parish instruction made the faith seem amorphous and unserious. It is to my credit, I think, that I rejected what I was offered and refused to be confirmed.

I was only converted because, through a series of crazy coincidences, I ended up attending the St. Ignatius Institute, a Great Books program that Ignatius Press founder Father Joseph Fessio had started in San Francisco. I was plunged into a community of sincere Catholics who embraced me and introduced me to the Faith.

The Institute curriculum, from Aristotle to Evelyn Waugh, helped me realize for the first time that truth existed and was knowable. A year abroad in England sealed the deal, where Oxford Dominicans taught me a lot and traveling Europe with my roommate taught me even more — he was the undergraduate version of the future world-renowned theologian Adrian Walker.

Back in San Francisco, I worked for the school newspaper, whose editors assigned me to research a recurring issue: Efforts of the administration to strip my program of its fidelity to the magisterium. The program stayed alive only because of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who had been Father Fessio’s thesis director. The priest maintained a lifelong relationship with his mentor. On several occasions, the powerful Vatican cardinal intervened for the school.

So I simultaneously discovered two things in college: First, that the Catholic faith was a vital part of who I was and integral to my happiness; and second, that I wouldn’t have discovered it, at all, without the repeated, direct intervention of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger.

He Put the Corbinian bear on his coat of arms — the animal forced to carry a saint’s baggage to Rome

A Light in the Shadows

After I graduated I worked as a journalist and as a Congressional press secretary, and eventually became the editor of the National Catholic Register.

It was my dream job, combining three great loves of my life: journalism, the Catholic Church, and my chosen home in the Church at that time, the Regnum Christi movement of the Legion of Christ, which owned the paper.

The job showed me that the Church was changing the world, not the other way around. We covered the new Catechism, which Cardinal Ratzinger used to address the vapid expression of the Faith that had repelled me as a child. We covered his Jesus of Nazareth book, which was translated by my old college roommate, Adrian Walker. And we covered the meteoric rise and triumphs of the Legion of Christ and its founder, Father Marcial Maciel.

And then we covered his ugly fall from grace when the shocking hidden depravity of Father Maciel’s secret life of sexual sin came to light.

It came to light, not coincidentally, shortly after Pope Benedict XVI became Pope. Father Maciel had been accused of crimes in 1997 but my friends and I had worked hard to convince ourselves — and others — that this was just an elaborate hoax.

That pretense became impossible after Benedict became Pope in 2005. In 2006, he removed Maciel from active ministry. The full news would be revealed three years later, when a communiqué from Benedict’s Vatican revealed that Maciel was guilty of “actual crimes” and lived “a life devoid of scruples and of genuine religious sentiment.”

It was devastating. I was totally disillusioned. That was good. I needed to be. To be disillusioned means to have an illusion taken away. I had been “disillusioned” before when I learned in college that the world was telling me lies. I was disillusioned now when I learned that some in the Church are as bad — no, worse — than the world.

The same man was a light in the shadows in both cases, taking away the comforting lie, and showing me the hard, but solid, truth.

I have been seeking that truth ever since, no longer willing to accept the easy version of the Faith’s answers, interrogating the sources — significantly, by following Ramage as he walks with Benedict through the morass of The Dark Passages of the Bible, The Historical Truths of the Gospels, The Theory of Evolution, and Nietzsche’s attack on what Benedict calls The Faith Experiment.

The Vatican’s Side Door

So, let me finish at last the story of my encounter with Pope Benedict XVI that happened 23 years ago.

I was conscious that I was approaching the man who saved the program that saved my soul. Later, he would remove a false prophet I was beholden to. Then, he would lead me through faith crises back to solid ground.

We exchanged smiles, and I advanced, notepad in hand. With a nod, Ratzinger reset the trajectory of his walk and gave me a wide berth, darting into a Vatican side door, out of reach.

He wasn’t the spotlight guy; he was the “humble worker in the Lord’s vineyard.” He didn’t want to chat. He was too busy doing the hard work that would transform the world.

Tom Hoopes is the former executive editor of the National Catholic Register and Faith & Family magazine, and the author of The Rosary of Saint John Paul II, The Fatima Family Handbook and What Pope Francis Really Said.

Tom Hoopes is the former executive editor of the National Catholic Register and Faith & Family magazine, and the author of The Rosary of Saint John Paul II, The Fatima Family Handbook and What Pope Francis Really Said.

Facebook Comments