By Federico Lombardi

The sudden death of Cardinal Julius Döpfner, Archbishop of Munich and undisputed leader of German Catholicism, would disrupt Ratzinger’s life just at the time of his having reached full academic and cultural maturity, at the age of 50. Paul VI asked him to take on the difficult task of succeeding Döpfner. It is not uncommon for Popes to think it appropriate to entrust the principal episcopal sees of Germany to individuals of high cultural standing. Ratzinger was a theologian of recognized status, had shown deep attachment to the Church during the postConciliar tensions and was also a “Bavarian patriot,” as he called himself. Acceptance was an “immensely difficult” decision for the professor, but the sense of readiness for the service required of him prevailed. On May 28, 1977, he was consecrated bishop. Paul VI immediately created him cardinal: on June 27 in Rome Ratzinger received the biretta.

As his episcopal motto, he chose Cooperatores veritatis (“Cooperators of truth”), a quotation from the Third Letter of St. John (1:8). One could hardly find words more expressive of the continuity between the theologian’s commitment to research and teaching and the bishop’s commitment to the magisterium and pastoral guidance. It would also apply to subsequent engagements: a splendid motto for a lifetime! His service as Archbishop of Munich was intense, due to the commitments involved in the pastoral care of the great archdiocese, but also quite brief. It coincided with “the year of the three popes” and the two conclaves (1978), and then with the election of Pope John Paul II and his first visit to Germany (1980), which concluded in Munich. John Paul II already knew and highly esteemed Ratzinger. He chose him as Relator of the 1980 Synod on the Family, the first of the new pontificate, and let him know immediately that he wished to have him in Rome at the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. At first Ratzinger resisted, but the Pope’s will was all too clear. On November 25, 1981, he was nominated prefect, and in March 1982 he moved to Rome.

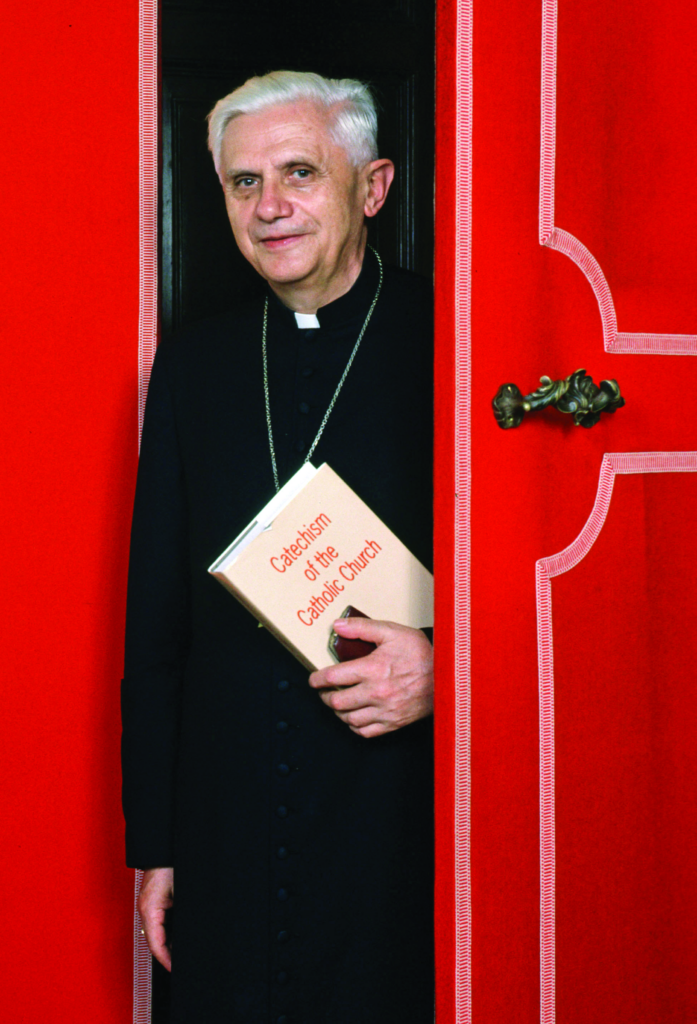

Cardinal Ratzinger holds 1992’s Catechism of the Catholic Church, for which he was largely responsible. (Photo Grzegorz Galazka)

The Cardinal Prefect

This new stage was a very long one. For 23 years Ratzinger was one of the main and most trusted collaborators of John Paul II, who would by no means be willing to give up his contribution to the life of the Church until the end of one of the longest pontificates in history. The relationship between the Pope and the prefect was intense, frank and cordial, based on mutual esteem and admiration, even allowing for the differences between the two personalities. Ratzinger thus certainly was one of the principal characters of this epoch in the life of the Church and he gave support of great theological depth to the magisterium of John Paul II, faithfully interpreting papal positions. It is quite natural to speak of an extraordinarily effective “formidable pair,” a great Pope and a great prefect.

The work accomplished by Cardinal Ratzinger in these years was impressive, thanks to his ability to guide the work of his collaborators, listening to them and directing their contributions with an extraordinary ability to synthesize, so that the documents are not so much the fruit of his personal work as of the effort of the whole group. But it would not be easy, because the debates in the postconciliar Church were heated theologically.

Three salient events can be highlighted among many of this period. First, the Congregation’s interventions on the topic of liberation theology in the early part of the 1980s. The Pope was deeply concerned about the influence of Marxist ideology on currents of thought in Latin American theology; the prefect shared his concern and faced the delicate problem with courage.

The outcome came in the form of the two famous Instructions, with the intention respectively to oppose negative drifts (the first, from 1984) and to recognize the value of positive aspects (the second, from 1986). Critical reactions, especially to the first document, and lively discussions were not lacking, including specific cases of individual controversial theologians (the best known of whom was the Brazilian, Leonardo Boff). Ratzinger, in spite of his acknowledged cultural finesse, did not escape the common fate of those in charge of the doctrinal dicastery of having the reputation of a rigid censor, guardian of orthodoxy and principal opponent of the freedom of theological research, and, being German, he would receive the hardly benevolent nickname of Panzerkardinal.

Another document of the Congregation, many years later, also gave rise to a wave of criticism: the Declaration Dominus Iesus, published during the Great Jubilee of 2000, on the centrality of the figure of Jesus for the salvation of all. This time it was mainly those circles most committed to ecumenical relations and dialogue with other religions that reacted. But even in this case there is no doubt that his stance fully corresponded to John Paul II’s intention to protect some essential points of the Church’s faith from misunderstandings or deviations with serious implications.

For 23 years, Ratzinger was one of the most trusted collaborators of John Paul II, Together they were an extraordinarily effective “formidable pair”

A New Catechism for the Church

A third endeavor, also at first much debated but eventually achieving wide consensus and success, was the truly herculean effort of drafting a new Catechism of the Catholic Church. An exposition of the entire Catholic faith, mirroring the conciliar renewal and formulated in language suited to today’s times, had been requested by the 1985 Synod. The Pope entrusted the task to Cardinal Ratzinger and a commission he chaired. The fact that after an era of very strong theological and ecclesial debates and tensions, within a few years, that is, already by 1992, the work came to fruition in a largely convincing way, has something miraculous about it.

Only an exceptional capacity for a unified vision of doctrine and the entire field of Christian life could guide the enterprise and come to terms with it. Sensitivity to contemporary expectations was not lacking. Are these not the same qualities we had recognized and admired 25 years earlier in the author of the Introduction to Christianity?

The Catechism remains probably the most significant positive doctrinal contribution of John Paul II’s pontificate, a valuable tool for the life of the Church: it is not for nothing that Pope Francis makes frequent reference to it.

Ratzinger had an extraordinary ability to guide his collaborators, listen to them and synthesize their work. It was not easy: debates in the post-conciliar Church were heated

Facebook Comments