We Will Not See Benedict’s Like Anytime Soon

By John Byron Kuhner

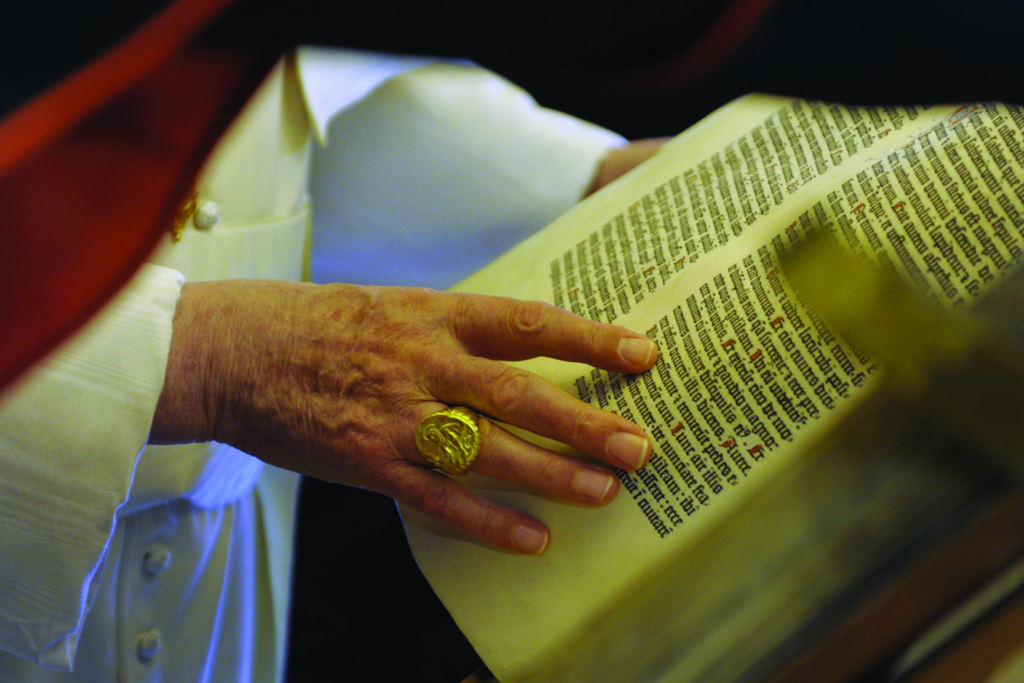

Dec. 18, 2010 – Vatican. Pope Benedict XVI reads a book during his visit to the Vatican Library. The library was reopened the previous September after being closed three years for major renovations (CNS photo/L’Osservatore Romano via Reuters)

An unusual thing happened at the Apostolic Palace when Fr. Reginald Foster and the rest of the Vatican’s Latin Office submitted their translation of Deus Caritas Est to the Vatican’s Secretariat of State in 2005. It came back to them. With edits. From the Pope. “A few times at the beginning John Paul II would change some of the Latin words, but only in a few very important places. Eventually he stopped. Not even he could read all the stuff he was writing, let alone read it in Latin.”

Benedict XVI was different. He had taken much of the first year of his pontificate writing this 16,000 word encyclical in German. It was then translated – extremely literally – into Italian. The Italian version was submitted to the Latin Office, who had to blitz their way through it in order to get it done by the Christmas release date.

“You can see right away that Italian wasn’t the original,” Foster said in an interview shortly after the publication. “I wanted to do it from German, the original was German and you can see it right away but they said ‘No, everybody’s translating from Italian.’ So we’re stuck with the Italian but you can see the Italians don’t like the Italian. So anyway, we did it.”

This was the kind of Italian the Latinists were being given: “Di fatto, tendenze in questo senso ci sono sempre state.” “In fact, tendencies in this direction there have always been.” It was not hard to see the German behind it: “Tendenzen in dieser Richtung hat es auch immer gegeben.” It became, in Latin, “Reapse in hanc partem proclivitates semper fuerunt.”….“Linguistic madness,” as Foster said. But the Latin is effective at reproducing the German: the German word order in particular is almost completely preserved.

Working from an Italian translation of a German document wasn’t the only problem. The content was, itself, difficult to express in Latin. Foster explained:

“The hardest is this modern – I won’t say modern, I have nothing against what’s modern – but is this jargon that we have… ‘a love of our friend turns our friend into a’ – not into ‘us’! – but into ‘a certain we’…. Unnhh! And they go on and on like this where you can’t… it’s impossible to translate some of this stuff. They never thought that way, the Romans just never thought that way…. Or ‘I’m going to miss a little of my own ego’… well, you have to say in Latin ‘my own person’ or something like that…. If you say mei, well, that’s a piece ‘of me’ but to say ‘I’m losing a piece of me’ and to say ‘I’m losing a piece of my ego,’ that’s another thing!”

However, Foster’s complaints about the process are not really discernible in the final text. It is, in fact, quite easy to understand:

Amor per amorem adolescit. Amor “divinus” est, quoniam ex Deo procedit isque nos cum Deo coniungit et hoc in unitatis processu in quiddam veluti “Nos” convertit, quod nostras partitiones praetergreditur et efficit ut unum fiamus, ita ut postremo Deus sit “omnia in omnibus.”

Love grows through love. Love is “divine” because it proceeds from God; and it joins us with God; and in this process of unifying it turns us into something like a “We,” because it transcends our divisions, and brings it about that we become one thing, so that finally God may be “all in all.”

In part this is because after all the “linguistic madness,” after all the jargon, Benedict sat down with the Latin text and read it. There wasn’t time for this, but he did it anyway. The document ended up being a month late, missing its Christmas release date. Benedict insisted on reading every word of it in Latin, changing certain phrasings, and standardizing the style of the whole (the Latin Office did documents piecemeal, with different translators taking up different parts of the document, and with rarely any editorial oversight over such niceties as consistent word choice and style throughout a document). The end result was much better workmanship than typically comes out of Vatican documents.

Benedict could do this, of course, because he knew Latin. This is not the case with Pope Francis, the first Pope formed after Paul VI repudiated Vatican II’s decree requiring Latin in the seminaries. Francis’ most recent (2020) encyclical Fratelli Tutti still has not received a Latin version and it appears it never will. It’s still too early to say that Benedict XVI will be the last Pope who knows Latin – history is full of surprises – but it’s hard to see the next Pope having Benedict-level competence in the subject. Benedict was so good at it that he wrote his own speeches in Latin without the Latin Office’s help – most notably, his resignation speech, which the Latin Office knew nothing about until he had actually given it and shocked the world.

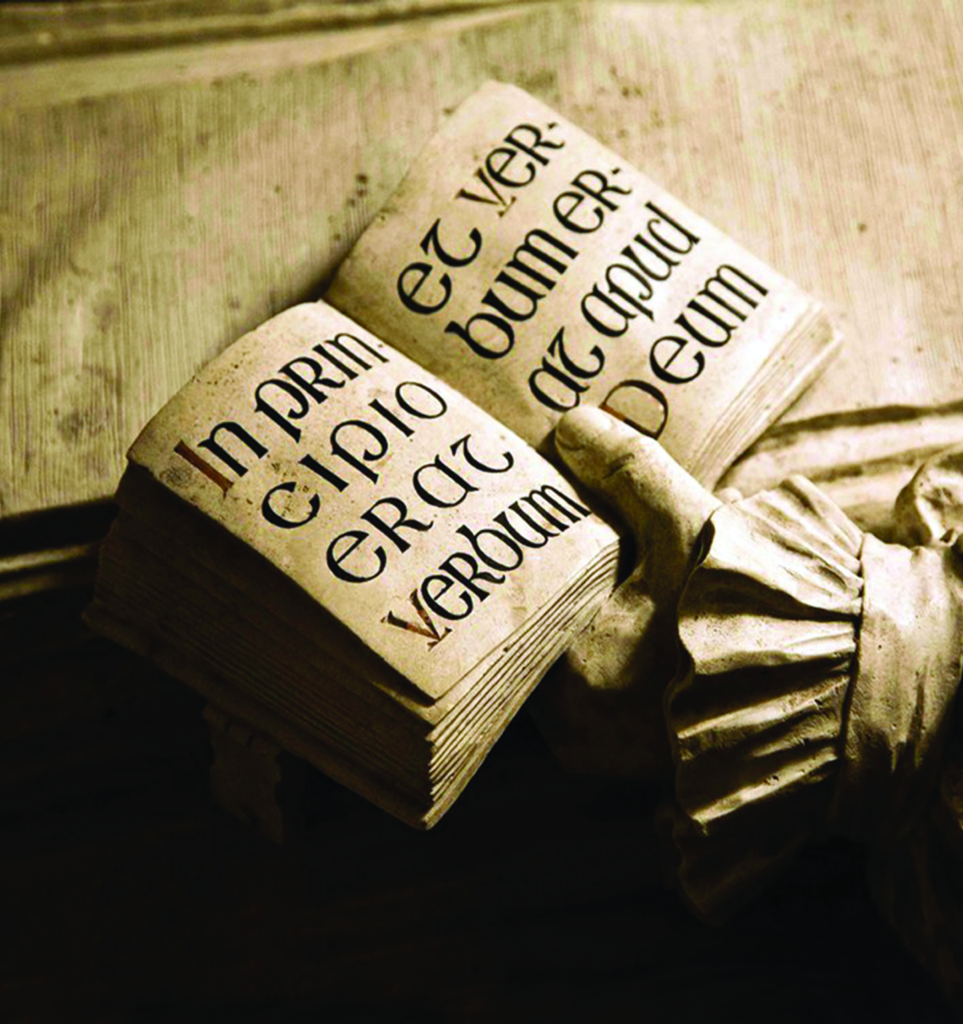

It is fitting that the Latin Pope would write about unity. The same thing Benedict says about Love, Popes have been saying for centuries about Latin: it transcends divisions, that we may become one with the Church through the ages; it drains away the ego, that God may be all in all; in its more elevated moments, in its grand prayers, otherworldly chants, and symphonic musicality, it joins us with God and seems indeed to come from God. Without it, and without the Latin Pope, it is hard not to fear a new era of division in the Church.

John Byron Kuhner is the former president of the North American Institute of Living Latin Studies (SALVI), and the editor of In Medias Res, the Paideia Institute’s online journal. He writes the regular Latin column for Inside the Vatican magazine.

Facebook Comments