By Robert Wiesner

Arianism was dealt a death blow at Nicaea, but as is common with such heresies, it took some time before its demise was completely recognized. Arius himself did not die until around 336, more than ten years after Nicaea. In fact, he died just at the time he was convinced that he had won the day with his twisted theology. Emperor Constantine himself directed Patriarch Alexander of Constantinople to receive Arius in his church to receive him into Communion. The Patriarch prayed that he might die before being placed in the position of extending the Eucharist to a heretic; God ordained otherwise. On the way to the church, the story goes, Arius felt himself overcome by the call of nature. He stepped into a public latrine, from which he never emerged. When his followers investigated they found Arius lying on the floor amid his intestines, having expired due to a prolapsed rectum! There is some reason to doubt this tale; the exact same end is recounted of several other heretics. There is also a good possibility that some of Arius’ opponents had him poisoned, a rather more plausible scenario. Sometimes even orthodox churchmen don’t fool around when combating heresy! In any event, Patriarch Alexander was spared the necessity of obeying the Emperor to the detriment of his soul.

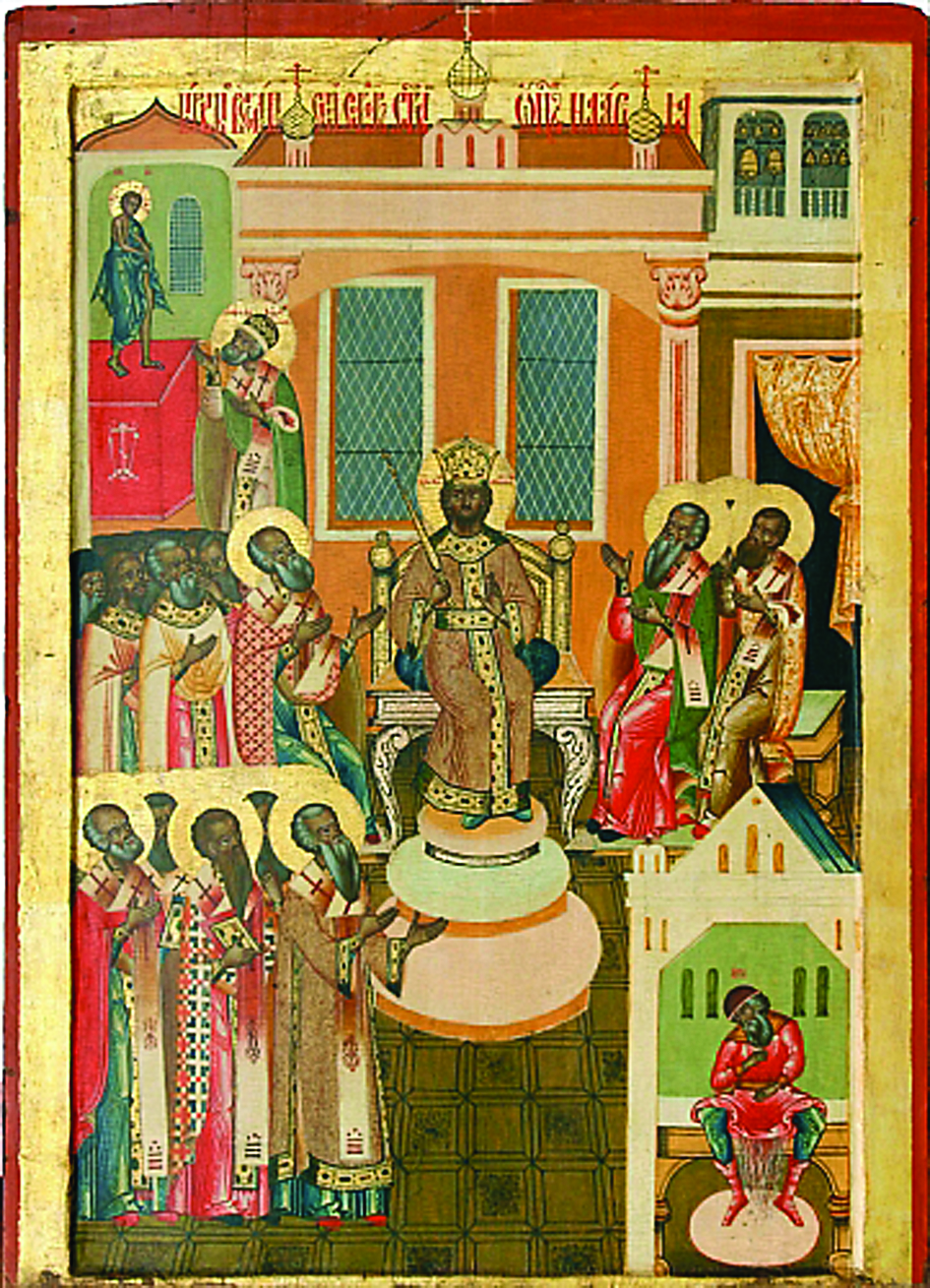

Arius was dead, but his heresy continued to cause division in the empire; it even spawned at least two other heretical movements. Macedonianism, proposed by Patriarch Macedonius of Constantinople, denied divinity and personhood to the Holy Spirit; his thinking essentially did to the Holy Spirit what Arius did to the Son. Apollinarianism, introduced by Apollinaris of Laodicea, held that Jesus Christ was somehow not really a unified God-Man, but that instead He had a human body and sensitive soul, but a divine mind rather than a human rational mind. Given the stubborn refusal of Arianism to completely die out and the rise of these similar heretical movements, unrest and violence continued to upset the peace of the empire. Finally, Emperor Theodosius I decided to call another council to definitively resolve the endless theological debates. Thus, one hundred fifty bishops convened at Constantinople in 381 under the leadership of St. Gregory of Nazianzus, the great Cappadocian Father who was Patriarch in Constantinople at the time.

In dealing with the last remnants of Arianism and the new offshoots of the heresy, Macedonianism and Apollinarianism, the Council Fathers found it expedient to revisit the Creed laid down at Nicaea in 325. Several articles of the original Creed were refined and clarified regarding the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, mostly dealing with the true divinity and true humanity of Jesus Christ. Thus the heretical positions of the Apollinarians were put to rest; this particular form of Arianism died out quickly after the Council.

Macedonianism posed a rather larger problem. The original Creed of 325 simply confined itself to a simple “We believe… in the Holy Spirit.” There was no elaboration on the theology of the Third Person, an oversight the Council Fathers corrected by a major addition to the Creed: “And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of life, Who proceeds from the Father, Who with the Father and the Son is worshiped and glorified, Who spoke through the prophets.” So was laid to rest the error of Macedonius. This heresy also disappeared shortly after the Council.

The other major change made to the original Creed was the deletion of the strong condemnation of Arianism which closed the Creed of 325. By that date Arianism itself was limited to only a few remote areas of the Empire and the need for such language was past.

Facebook Comments