“The splendour of truth shines forth in all the works of the Creator and, in a special way, in man, created in the image and likeness of God (cf. Gen 1:26). Truth enlightens man’s intelligence and shapes his freedom, leading him to know and love the Lord.” —St. John Paul II, Veritatis Splendor (in English, literally, “Of truth the splendor” or perhaps even “Of truth the overpowering light”). These are the very first words of this great encyclical

The Pilgrimage of Vittorio Messori

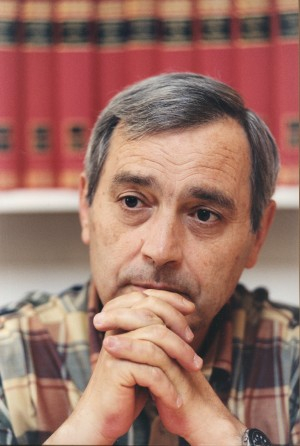

Vittorio Messori (photo above) is one of the great Italian Catholic journalists and writers of our time, and his work has been an inspiration and model for my own.

Messori’s most famous work was The Ratzinger Report (1985), the distillation of several days of interviews in a northern Italian monastery with then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, then head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which Messori published in Italian in 1984, the year I arrived in Italy, as Rapporto sulla Fede — “Report on the Faith.” A modest title for a blockbuster book. (Father Joseph Fessio, S.J., of Ignatius Press, once told me that the success of that book provided perhaps half of all of the revenues of his press in those middle years of the 1980s.)

Coming 20 years after the close of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), the interview book with Ratzinger made clear that there was still “much to be done” for the Church to grasp fully what the Council had meant, and that there were profound dangers for the faith lurking in certain modern, post-Conciliar trends — above all, “the dictatorship of relativism,” which insisted that truth was not knowable, or if knowable, not universally reliable or applicable. Why do we speak of such things as “profound dangers”? Because they are dangers to the person, to the individual soul, causing worry, indecision, confusion, and even despair.

The “dictatorship of relativism” — which essentially said there is no universal truth that all men should know and be heartened and comforted by — left modern man bereft, without a reliable compass in this world.

Ratzinger’s entire work up to today — and still continuing — may be understood as a long effort to overcome this “bereftness,” this loss of the compass provided by incontestable truth. (See the great encyclical of Pope John Paul II which Ratzinger helped to compose, Veritatis Splendor, August 6, 1993, for a soaring treatment of this matter.)

So Messori, during and after his religious conversion, spent many years writing other books, all focused on setting forth the evidence for the truth of the Gospels — compiling the evidence for the historicity of the life, teaching, suffering, death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth.

So when I saw this interview with Messori two days ago, I was deeply moved.

Messori tells us here about his journey toward faith.

I realize well that we are passing through a difficult time, a time of controversy in the Church, confusion, lockdowns, travel restrictions, economic uncertainty — and these topics will provide material for future letters.

But this Letter, which contains the story of Vittorio Messori, through the excellent work of Solène Tadié, of the National Catholic Register (link), is perhaps more important than any of them.

At the heart of the story is the longing of the human heart for truth, and the pain that longing causes, until the truth is heard, understood, marveled at, embraced, believed, rendered fruitful in life.

Messori, in the interview below, describes this experience, which is the drama of the soul.

And we must recall that the soul is the most important thing, that spark of life and personhood within us which lives on the level of choice, of right and wrong, of repentance and grace, of love.

This interview tells in a marvelous way of that dramatic journey, and for this reason, I wished to share it with you, with much thanks to Solène Tadié and the National Catholic Register. —RM

Prominent Italian Catholic Journalist: ‘The Gospel Is Historically Reliable’

On the occasion of the republishing of his historical inquiry on the passion and death of Jesus, Vittorio Messori reaffirms the urgency of announcing the truth of Christianity to a secularized modern world.

By Solène Tadié, National Catholic Register (link)

ROME — In a world where atheistic materialism is predominant in countless countries and cultures, the Catholic Church cannot teach the truth of Christ without recalling that faith and reason are compatible and in some ways interdependent.

This Catholic approach, brought up to date by John Paul II in his encyclical Fides et Ratio (1998), posits that “faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth.”

As the postmodern West continues sinking into relativism and moral disarray, many respected Catholic intellectuals are doing their part to offer this treasure to the world.

One of them is Vittorio Messori, an Italian journalist and writer who converted to Catholicism in adulthood and has since dedicated his long and fruitful career to a historical study of the Gospel to demonstrate its authenticity.

Considered one of the most widely read and translated Catholic authors worldwide, and quoted in Pope Benedict XVI’s book Jesus of Nazareth, Messori has been producing a number of important apologetic works. Among his most widely read and acclaimed works are a series of investigation on the historicity of Christ and the mystery of his passion, death and resurrection: The Jesus Hypotheses (1976), Patì sotto Ponzio Pilato (He Suffered Under Pontius Pilate, 1992), and Dicono che è risorto (They Say He Is Risen, 2000)) — all of which are being republished in Italy by Edizioni Ares.

He is also the author of The Ratzinger Report (1985), a best-selling interview-book with then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger that focuses on the state of the Church in the aftermath of the Second Vatican Council.

Messori spoke in a lengthy interview with the Register on the occasion of the republication of Patì sotto Ponzio Pilato in Italy. He discusses his personal path of faith as well as the reasons why he thinks it is more necessary than ever to reaffirm the Good News as a central part of the Christian life by reaffirming the historical value of the four Gospels.

In your book Patì Sotto Ponzio Pilato, you insist on the fact that the Paschal mystery, the mystery of Jesus’ passion and death, is the primary core of the Gospels. You also quote Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, who recalled that the commandment “Let us love one another” does not assume its full meaning without the preamble of Christ’s death. In your opinion, is there a deviation in the understanding of the Christian message in today’s world?

Vittorio Messori: Cardinal Martini said something right here. The Gospel was a little moralized as mere human fables. Too often, we tend to reduce it to the practice of good deeds, like helping our neighbors, welcome refugees, build homes for the elderly, etc. It becomes a Gospel based on good intentions, reducing it to a kind of humanism. But we must remember that the main teaching of the Gospel is not goodness; it is not about supporting all those who are in need around us, even if, of course, these deeds are necessary. But what we must never forget is that the word “Gospel,” which comes from Greek euangélion, means “Good News.” The first purpose of the Gospel, from which the good deeds also flow, is to announce the Good News that Jesus Christ defeated death and opened the doors of heaven.

Christ didn’t come to teach us how to make good deeds before anything else. In reality, our good deeds are a consequence of the Good News. The priority is to open the doors of heaven to ourselves. In the same way, the crisis of the priesthood nowadays derives from the fact that many priests have forgotten that their first duty is to announce to their flock the Gospel and the resurrection of Christ, which proved that he really was the Son of God.

You speak indeed about the “spiritualistic and moralistic reduction” which is often made of the person of Christ, seeing him as a sort of “Jewish Socrates.” How did we come to such a situation?

Messori: For many, Catholicism was turned into a kind of humanism. But there is no need for the Gospel to be reduced to humanism. Many atheists consider themselves humanists. On the contrary, however, a Catholic does good deeds within the framework of the Gospel, anticipating his life in heaven. A Catholic is called to be charitable, generous, to help the poor, but it is in the name of Christ that he does so, in order to go to heaven.

This situation is, of course, a consequence of the Age of Enlightenment promoted by French, English and German thinkers in the 18th century; but this long process didn’t spare the Catholic world itself. If you take a look at many Catholic newspapers nowadays, you may think that they are written by generous — but very secular — people, nothing more. This issue has become a general one.

Do you think that popular faith can be rekindled by demonstrating the historicity of Jesus’ death and resurrection?

Messori: When I published my first book Ipotesi su Gesù (The Jesus Hypotheses), I did imagine that it would be of interest to people, but I couldn’t imagine the cataclysm it provoked. Two million copies were sold in Italy alone.

Relying on my own experience, I could say that countless people are willing to learn more about Christ and his life; they are eager to deepen their knowledge about him. Many priests today are reluctant to speak about Jesus Christ, because they think that the truth about his existence and sacrifice is no longer acceptable to the common man.

I think they are wrong. People just need to hear the answer to one fundamental question: Are the claims of the Gospel true or not? I have received about 20,000 letters from readers in reaction to my books over the past years. Whether they were supportive or not, they are a proof of the deep interest that Christ still arouses in people’s hearts.

How historically reliable are the biblical accounts of Jesus’ passion and death as a whole? Is it possible, like some critics claim, that the evangelists may have wrongly interpreted or even manipulated some facts that actually happened?

Messori: Like I said in the subtitle of my book, I made a historical investigation. I am above all a historian, even if I am a believing historian. I’ve been studying in every detail, word by word, everything the four Gospels say about the passion and death of Christ, while having a good knowledge of Jewish and Roman history. No one could challenge the historical truth. The possibilities to destroy the facts exposed in my book are equivalent to zero because everything I wrote to prove the truth of the passion and death of Christ is part of a history that we can totally demonstrate.

Then regarding the possible misinterpretation by the Evangelists, I would say that many versions were circulating in the years following the resurrection of Christ — at least 20 — and the Church selected only four of them because they were the most reliable. The authentic Gospel authors were writing in the heat of the moment —soon after Christ’s death and resurrection — so we have testimonies which derive directly from those who lived these events.

Among the forgotten truths about the Gospels, you also evoke the question of the original language in which they were written — as three languages were spoken in the Holy Land at that time: Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic. What did you find out?

Messori: The four Gospels first emerged in what we may call the English language of that time, that is Greek, which was then the most widespread language in the civilized world. But it is also probable that two of them were written in Aramaic. Hebrew was the language of the liturgy, whereas Aramaic was the popular language. This historical study is important. For instance, we know that the Gospel of Matthew, written by a Jewish disciple of Christ, was composed in Aramaic. It is important to try to understand the original Aramaic words that were translated in Greek and to have a more precise knowledge on the origin of the Scripture — but the original language doesn’t change the truth of the Gospel episodes.

Is it really possible to carry out an objective research on the Gospels as a believer?

Messori: My conversion happened while studying the Gospel. Then I started what would become a long investigation of its historicity. Well, if I had found out that something didn’t match with the historical reality, I would simply have abandoned my rising Catholic faith. It wouldn’t have damaged my career. On the contrary! Everything would have been easier. I am not a priest; I am a scholar and a journalist, and I have no interest in promoting a faith which relies on false teachings.

And now, the more I move forward in my life, the more I am convinced I was not wrong and that the Gospel is truly a mystery that must be explored and embraced.

What was the impact of your research and writings on your personal life?

Messori: I’ve never been to Catholic schools nor seminaries. I got called by the Lord when I least expected it. It just happened to me like a bolt of lightning; it was very mysterious. I would have never imagined that one day I would become a Catholic. My family, especially my parents, weren’t Catholics — they were even anti-clerical. At the beginning, I used to go to Mass secretly, and my parents were saddened when they found out. My mother even thought I was having a nervous breakdown and she asked a doctor to see me.

At the university, I was about to become a probationary lecturer. But my conversion had a negative impact on my academic career. When my professors found out that I had become a Catholic, they were no longer willing to make a man like me their successor.

At school and then at the university, we never spoke about religion, and when we did, it was to refer to a bygone phenomenon.

So I used to be an agnostic; but then, one day, I had a conversion, which was first of all intellectual, when I understood the authenticity of the Gospel. I got passionate about the history of the Gospel, and this is how it all started.

In 40 years of work, I’ve published 24 books, all related to apologetics. The attempts of my books are to show modern man that it is still possible to believe in the Gospel. All these years, I’ve been trying to prove something I’d been doubting the first part of my life: that is, the fact that the Gospel is historically reliable, that everything truly happened. All the truth of the Gospel is summed up in one event only, that is, the passion, death and resurrection of Christ.

My three books that are being republished, Ipotesi su Gesù, Patì sotto Ponzio Pilato, and Dicono che è risorto, offer an in-depth study and investigation on this event that changed the course of history. They are the pillars that support the whole structure of my thought.

The funny thing is that, in all these years, my work has only been criticized for the moral and philosophical ideas it conveyed, but never on the facts and on the truth of my findings. But I’ve always spoken as a journalist, and I’ve been constantly studying to give my readers the most credible information. For this reason, I’ve always tried to produce authoritative works.

You personally know Pope Benedict XVI, as you wrote a book-interview with him when he was still Cardinal Ratzinger. And in his book Jesus of Nazareth, he mentioned your work as an important reference on this matter. What memories do you have of your exchanges?

Messori: I was very friendly with Joseph Ratzinger when he was a cardinal. The book we wrote together didn’t go unnoticed, indeed, and had a wide coverage worldwide, as it was the first time that the prefect of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) confided in a journalist. We used to go to lunch together every time I visited him in Rome. We would always tease each other on the peculiarity of our relationship, as it was not common at that time for clerics and journalists to be associated so closely.

He is the kindest and most understanding person I’ve ever met. The fact that he was presented like the “great inquisitor of the Holy Office”— just as if he was preventing the Church from evolving — has always made me smile. In reality, Ratzinger was — and still is — above all a scholar, a professor. He used to be very happy when he taught at the German university.

He would always say he didn’t feel he was able to watch over the work of his Catholic colleagues and call them to order. He asked John Paul II three times to retire from his position as prefect at the CDF, but the latter refused every time. He used to say that it was not his job, that he was a simple professor. I was always struck by his humility. I see him as a very good candidate for heaven.

Solène Tadié is the Register’s Rome-based Europe correspondent.

Note: Here is another interview with Messori, conducted by Italian author Aurelio Porfiri. (link)

Facebook Comments