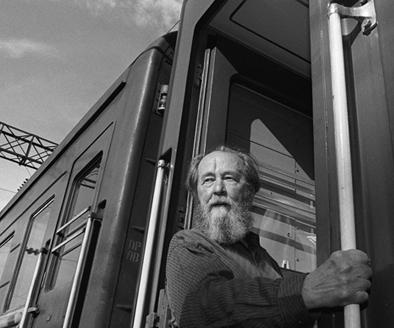

Alexander Solzhenitsyn in Zurich, Switzerland in 1974. He died in 2008. He was one of Russia’s greatest writers (link)

“It pains me to write this as Ukraine and Russia are merged in my blood, in my heart, and in my thoughts. But extensive experience of friendly contacts with Ukrainians in the camps has shown me how much of a painful grudge they hold. Our generation will not escape from paying for the mistakes of our fathers.” —Alexander Solzhenitsyn, 1968, as he wrote what would become The Gulag Archipelago

Letter #40, 2022, Tuesday, February 22: Ukraine

The hopes and fears of many are today implicated in the events in Ukraine.

I too have traveled in Ukraine, and in Russia, and felt the warm kindness of many in both countries.

My sons in 2013 traveled all the way across Russia on the Trans-Siberian Railroad, and for hour upon hour watched the white birches pass by, and met my friend Dmitry Khafizov in Kazan, where he took care of them for several days (he has now passed away; may he rest in peace, and may eternal light shine upon him).

And then, after Moscow, and meeting other friends there, the boys traveled to Kiev, Ukraine, and then to a little village outside of Kiev, called Lishnya, and there, in a little chapel, they were asked to sing a male part along with a group of women, in a liturgy, and they tried their best, and afterwards, the old women held up their hands, and smiled, and sang, and praised the boys, and thanked the boys for their efforts.

Fragments of memories, songs sung together, friendships shared, as the train rolled through the endless landscape, finally arriving in Rome, and a meeting with Pope Francis, who asked the boys how it had been to travel across Mongolia, Russia, Ukraine…

May all of these lands be blessed…

***

Many years ago, the great Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote about the relations between Russia and Ukraine, and between Russians and Ukrainians.

He said the very process of writing on these matters “pained” him… because “Ukraine and Russia are merged in my blood, in my heart, and in my thoughts,” even as he understood, from conversations with Ukrainians in the Soviet labor camps, “how much of a painful grudge” many Ukrainians held against Russians.

“Our generation will not escape from paying for the mistakes of our fathers,” he wrote.

As events have unfolded in recent days, two extreme positions — love and hate, unity and division, friendship and enmity (mostly the negative one of these pairs) — have alternated in the media of the world, as it reports on the events along the border of Ukraine and Russia, in the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine.

I would like here to highlight the positive side, if possible…

The side which speaks of friendship, of gratitude, of healing, of bread shared at a table, of hope for a better future…

So I offer this brief reflection on Solzhenitsyn’s words on these matters — prepared some years ago by the British writer Dr. Joseph Pearce — in the hope that they may somehow help to bring deeper understanding, and even reconciliation, in a situation which seems fraught with danger for the two countries, and for our whole world…

May some spiritual assistance allow, even now, the coming of peace in this intensifying conflict.

As my father always said to all of us, “Maria, ora pro nobis” — “Mary, pray for us.”—RM

A native of England, Dr. Joseph Pearce converted to Catholicism in 1989, repudiated his earlier views not in keeping with his new faith, and became an internationally acclaimed author.

A native of England, Dr. Joseph Pearce converted to Catholicism in 1989, repudiated his earlier views not in keeping with his new faith, and became an internationally acclaimed author.

Among his bestsellers are The Quest for Shakespeare, Tolkien: Man and Myth, The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde, C. S. Lewis and The Catholic Church, Literary Converts, Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G.K. Chesterton, Solzhenitsyn: A Soul in Exile, and Old Thunder: A Life of Hilaire Belloc.

Dr. Pearce joined Inside the Vatican for a Writer’s Chat in March 2021. This Writer’s Chat is available on our YouTube channel here.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Photo by I, Evstafiev, CC BY-SA 3.0, (link)

The Voice of a Prophet: Solzhenitsyn on the Ukraine Crisis (link)

By Joseph Pearce

(originally published on June 6, 2014, in the Imaginative Conservative)

Though Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) feared the consequences of an independent Ukraine, he respected the right of the Ukrainian people to secede, a right which they duly exercised as the former Soviet Union unraveled. [in 1991].

Reiterating his subsidiarist principles, he insisted once again that “only the local population can decide the fate of their locality, of their region.”

Alexander Solzhenitsyn was many things.

A fearless champion of freedom in an age of totalitarianism.

A fearless critic of Communism.

A fearless critic of the modern hedonistic West.

A great historian.

A great novelist.

A Nobel Prize winner.

A prophet.

Regarding the last of these, Solzhenitsyn prophesied, at the height of the Soviet Union’s power, that he would outlive the USSR and would return to his native Russia after the Soviet Union’s demise.

As is the fate of prophets, he was not taken seriously.

It was assumed by all the “experts” that the Soviet Empire was here to stay and would be part of the global geo-political landscape for the foreseeable future.

As history has attested, the prophet was right and the experts wrong.

Clearly Solzhenitsyn is worth taking seriously.

Nowhere is this more evident than in his remarkable prescience about the present crisis in the Ukraine.

As far back as 1968, during his writing of what would later be published as The Gulag Archipelago, he wrote of his fears of future conflict between Russia and the Ukraine: “It pains me to write this as Ukraine and Russia are merged in my blood, in my heart, and in my thoughts. But extensive experience of friendly contacts with Ukrainians in the camps has shown me how much of a painful grudge they hold. Our generation will not escape from paying for the mistakes of our fathers.”

Foreseeing the rise of nationalism and its territorial claims, Solzhenitsyn lamented that it was much easier “to stamp one’s foot and shout This is mine!” than to seek reconciliation and co-existence. He wrote:

Surprising as it may be, the Marxist teaching prediction that nationalism is fading has not come true. On the contrary, in an age of nuclear research and cybernetics, it has for some reason flourished. And time is coming for us, whether we like it or not, to repay all the promissory notes of self-determination and independence; do it ourselves rather than wait to be burnt at the stake, drowned in a river or beheaded. We must prove whether we are a great nation not with the vastness of our territory or the number of peoples in our care, but with the greatness of our deeds.

Russia, Solzhenitsyn argued, should be content with “ploughing what we shall have left after those lands that will not want to stay with us secede.”

In the case of the Ukraine, Solzhenitsyn predicted that “things will get extremely painful.”

It was necessary, however, for Russians “to understand the degree of tension” that the Ukrainians feel.

With his customary grasp of history, he lamented that it had proved impossible over the centuries to resolve the differences between the Russian and the Ukrainian people, making it necessary for the Russians “to show good sense”: “We must hand over the decision-making to them: federalists or separatists, whichever of them wins. Not to give in would be mad and cruel. The more lenient, patient, coherent we now are, the more hope there will be to restore unity in future.”

The greatest difficulty arose from the ethnic mix in the Ukraine itself in which, in different regions of the country, there were different proportions of those who consider themselves Ukrainians, those who consider themselves Russians and those who consider themselves neither. “Maybe it will be necessary to have a referendum in each region and then ensure preferential and delicate treatment of those who would want to leave.”

For this to happen, the Ukraine would need to show the same restraint and good sense towards the regions in which Russians predominated as Russia needed to show to the Ukraine as a whole.

This was especially necessary because of the arbitrary nature of the area designated as belonging to the Ukraine: “Not the whole of Ukraine in its current formal Soviet borders is indeed Ukraine. Some regions … clearly lean more towards Russia. As for Crimea, Khrushchev’s decision [in 1954] to hand it over to Ukraine was totally arbitrary.”

The way in which ethnic Ukrainians treated the ethnic Russians within these largely arbitrary borders would “serve as a test”: “while demanding justice for themselves, how just will the Ukrainians be to Carpathian Russians?”

Several years later [after 1968], in April 1981, Solzhenitsyn wrote a letter to the Toronto conference on Russian-Ukrainian relations in which he wrote that “the Russian-Ukrainian problem is one of the major current issues and, certainly, of crucial importance to our peoples.”

The problem was, however, exacerbated by “the red-hot passion and the resultant sizzling temperatures” which were “pernicious”: “I have repeatedly stated and am reiterating here and now that no one can be retained by force, none of the antagonists should resort to coercion towards the other side or towards its own side, the people on the whole or any small minority it embraces, for each minority contains, in turn, its own minority.”

Following the principles of subsidiarity which had always animated his political thought, Solzhenitsyn insisted on the rights of localities to determine their own destinies, free from the coercive force of alien and alienating central government, whether that government was in Moscow or Kiev: “In all cases local opinion must be identified and implemented. Therefore, all issues can be truly resolved only by the local population ….”

Meanwhile, the “fierce intolerance” that animated extremists on both sides of the ethnic divide would be “fatal to both nations and beneficial only for their enemies.”

In 1990, in his seminal and groundbreaking book, Rebuilding Russia, Solzhenitsyn prophesied the danger inherent in the ethnic composition of the Ukraine:

To separate Ukraine today means to cut through millions of families and people: just consider how mixed the population is; there are whole regions with a predominantly Russian population; how many people there are who find it difficult to choose which of the two nationalities they belong to; how many people are of mixed origin; how many mixed marriages there are (by the way, nobody has until now thought of them as mixed).

Although Solzhenitsyn feared the consequences of an independent Ukraine, he respected the right of the Ukrainian people to secede, a right which they duly exercised as the former Soviet Union unraveled.

Reiterating his subsidiarist principles he insisted once again that “only the local population … can decide the fate of their locality, of their region, while each newly formed ethnic minority in that locality should be treated with the same non-violence.”

Today, almost six years after his death [Pearce is writing in 2014; Solzhenitsyn died in 2008], Solzhenitsyn’s position is still the only sane and safe solution to the Ukrainian crisis.

Those regions of eastern Ukraine which desire to secede from the Ukrainian-dominated west of the country should be allowed to do so.

There are already two nations in the de facto sense.

It makes sense, therefore, that this de facto reality should be honoured with de jure status.

Any other suggested solution is not only unjust but will lead to even greater injustice in the form of war, terrorism and hatred.

In this, as in so much else, the voice of the prophet should be heeded.

[End]

And here is an article published in Time magazine just after Solzhenitsyn’s death in 2008.

Remembering Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (link)

By Lev Grossman

Time, Monday, August 4, 2008

Russian author Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, pictured in Zurich in 1974, died in Moscow on August 3 [2008]

Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, the Nobel Prize-winning author whose novels chronicled the daily horrors of life in Soviet gulags, has died from heart failure on August 3 in Moscow at age 89, the Associated Press reported.

It was always Aleksander Solzhenitsyn’s ambition to be a writer.

He read War and Peace in its entirety when he was only 10.

But as a young man he couldn’t get his work published, and he wound up studying mathematics in college.

Then he was drafted into the Red Army in 1941.

If it weren’t for Stalin, his ambition might have gone unfulfilled.

Solzhenitsyn was born in a resort town in the Caucasus mountains in 1918, the same year the last czar of Russia was murdered by the Bolsheviks.

He never knew his father, an artillery officer who died in a hunting accident while his mother was pregnant.

His mother was a typist.

A zealous communist, Solzhenitsyn served with distinction in World War II, but in 1945, in the teeth of the Red Army’s march on Berlin, he was arrested for a personal letter that contained passages critical of Stalin and sentenced to eight years in a labor camp.

His life as a free man was over, but his life as a writer and a thinker had just begun.

Solzhenitsyn was eventually transferred from the camp to a prison with research facilities, and then in 1950 — when he would no longer cooperate with the government’s research efforts — to a harsher camp in Kazakhstan.

There he began to write on stray scraps of paper.

Once he memorized what he had written, he would destroy the scraps.

By the time he was released in 1953, Solzhenitsyn’s belief in communism was gone, but he had found a fervent Russian Orthodox faith and rediscovered his purpose as an author.

At first he wrote for himself, but by 1962, when he was 42, the strain of remaining silent had grown unbearable, and the cultural climate had warmed enough that he was able to publish his novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, an account of an innocent man’s experiences in a political prison camp, enduring brutal conditions without self-pity and taking solace from tiny pleasures, like a cigarette, or extra soup.

It’s a stunning work of close observation and simple description, and a devastating study of the psychology of oppression.

It was also the first published account of life in a Soviet labor camp.

Its appearance was a seismic event in Russian culture.

For a time, the Soviet government tolerated Solzhenitsyn.

Khrushchev was eager to discredit Stalin and consolidate his own power, and Solzhenitsyn’s work served his political aims. He became a global literary celebrity.

But he quickly outlived his political usefulness, and his next two books, The First Circle and The Cancer Ward, had to be published abroad.

In 1970 Solzhenitsyn won the Nobel prize for literature, but he wasn’t permitted to leave the country to accept it.

In 1973 he completed the first volume of The Gulag Archipelago, a thundering, encyclopedic indictment of the Soviet labor camp system and the government that built it which combines literary fiction with the testimony of hundreds of actual survivors. It is a towering monument to the power of witness.

In The First Circle Solzhenitsyn wrote: “For a country to have a great writer is like having another government. That’s why no regime has ever loved great writers, only minor ones.”

With The Gulag Archipelago Solzhenitsyn had become too great for the Soviet government.

After years of harassment he was put on a plane and expelled from Russia.

Thus began a strange new life for Solzhenitsyn.

With his wife and three sons he settled on a 50-acre compound in rural Vermont, where he preserved every aspect of Russian life that he could.

Once a year he would commemorate the day of his arrest with a ‘convict’s day,’ when he reverted to the diet of bread, broth and oats he ate in the labor camps.

He rose early every day and wrote until dusk — producing, among other works, his novel-cycle The Red Wheel, a vast, Tolstoyan account of the Russian revolution that runs to 6,000 pages, beginning with August 1914.

Solzhenitsyn was an icon of freedom to the Western world, but he did not return the esteem it heaped on him.

As a man of enormous Christian faith, he regarded the West as spiritually deteriorated, and he sometimes baffled supporters and critics alike with his reactionary criticisms of Western democracy.

In a searing speech to Harvard’s graduating class of 1978, he observed that “a decline in courage may be the most striking feature that an outside observer notices in the West today.”

Then what Solzhenitsyn had long predicted came to pass: the Soviet Union ceased to be.

In 1994, at age 75, a bearded, patriarchal Solzhenitsyn returned from exile to his native Russia, where he was welcomed as a hero, the prophet of the post-Soviet era.

But his home had become strange to him.

He had imagined himself as the conscience of his native land, and he certainly commanded a great deal of cultural authority — he was given his own TV show, and in 2007 Vladimir Putin visited him personally to present him with a state medal.

But he was never quite in step with the new Russia.

To Solzhenitsyn, Russia meant the old Russia of the 19th century, a nostalgic, spiritual Russia of the soul.

To Russians, Russia was something else — an increasingly Western and forward-looking and materialistic nation.

But Solzhenitsyn remained hopeful that the coming centuries would bring with them a world where mankind’s material and spiritual lives, our bodies and our souls, would be able to flourish together.

After personally enduring and bearing witness to some of the greatest tragedies of a tragic century, he still believed that life could and would evolve and improve.

“The ascension is similar to climbing onto the next anthropological stage,” he said. “No one on earth has any other way left but upward.”

[End]

Facebook Comments