“Gentlemen may cry, ‘Peace,’ ‘Peace’ – but there is no peace…” —Patrick Henry, in the Virginia House of Burgesses, 1775 (link)

“Providing lethal aid to Ukraine would exploit Russia’s greatest point of external vulnerability. But any increase in U.S. military arms and advice to Ukraine would need to be carefully calibrated to increase the costs to Russia of sustaining its existing commitment without provoking a much wider conflict in which Russia, by reason of proximity, would have significant advantages.” —from an April 24, 2019, Rand Corporation study on “Overextending and Unbalancing Russia.” The RAND Corporation, according to its own website, “is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest.” The report proposes that Russia be weakened by “providing lethal aid to Ukraine.” The report was prepared and completed three years ago.

Letter #58, 2022, Tuesday, March 29: No peace

Almost 250 years ago, in 1775 on the eve of the Revolutionary War with Great Britain, Patrick Henry of Virginia — ancestor of a close colleague of mine — gave one of the most famous speeches in American history.

He celebrated freedom, saying freedom is so important that it is worth breaking the apparent peace for — that it is worth fighting for.

Here is the extended version of the quotation:

“It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry, ‘Peace,’ ‘Peace’ – but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field!

“Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

Memorable words.

Stirring words.

But these words do not prompt in me a reflection on the necessity of fighting wars to preserve freedom.

Rather, they prompt in me the thought that one supreme task of free men is to build, before any war, a durable civilization of “ordered liberty” — ordered freedom — so that the “chains and slavery” that would prompt those who love freedom to take up arms are not threatened, or imposed…

Within nations, this is the task of politics, of striving to find the “common good” through difficult, but finally honest and fair, compromises.

Between nations, that is, worldwide, this is the task of finding and protecting the same “common good” in a much wider arena, an arena crowded with protagonists and interest groups who all, naturally, seek their own advantage.

The task is not easy — King George, for one, did not find the way.

So, human history has been filled with war, conquest, plunder, executions, enslavements.

Yet, the Christian faith urges us to be “peacemakers.”

Such, Christ taught us, will be called the sons and daughters of God.

Then what is the task if we wish to be “peacemakers” and therefore seek the paths leading to world peace?

Such a peace must take into account the anxieties of all, small as well as large nations, poor as well as rich nations, developing and developed nations alike, so that those who, with Patrick Henry, might fear to lose their freedom, might receive reasonable proposals to consider, and might decide to accept such proposals as worthy of the dignity of free men and women.

Only such a process can lead to the “tranquillity,” the peacefulness, of a free society — a nation, or a world, where justice, fairness, and the rule of good laws will provide a secure framework for a peace that protects and preserves human freedom.

***

During the 20th century, terrible wars were fought, and millions upon millions died.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, 30 years have passed — a generation… the whole middle decades of my own life.

And during these years, there have been many attempts to build an architecture which might support and protect a durable international peace.

Yes, during these years, there have also been unrelenting efforts to carry on international conflicts “by other means.”

The years of peace since 1991 have not really been years of peace.

As Patrick Henry announced, “The war is actually begun.”

Pope Francis attempted to tell us all that this was the case when he announced several years ago that “World War III has already begun”… in piecemeal fashion, here and there, in various corners of the globe, in proxy wars, in simmering violence, in the preparations for war (link).

On August 18, 2014 — almost exactly 100 years after the start of the First World War in 1914 — during a press conference on the flight from Korea to Rome, Pope Francis said: “Today we are in a world at war everywhere! Someone told me, ‘You know, Father, we are in the Third World War, but it is being fought piecemeal.’” (link)

One example of this is in the excerpts I republish below from a comprehensive Rand Corporation study first issued in 2019, almost three years ago. (link)

Entitled “Overextending and Unbalancing Russia,” this report sets forth many different way to accomplish that “overextending” and “unbalancing” — goals that are presented as self-evident goals of American foreign policy.

“This brief summarizes a report that comprehensively examines nonviolent, cost-imposing options that the United States and its allies could pursue across economic, political, and military areas to stress — overextend and unbalance — Russia’s economy and armed forces and the regime’s political standing at home and abroad,” the opening cover letter begins. “A team of RAND experts developed economic, geopolitical, ideological, informational, and military options and qualitatively assessed them in terms of their likelihood of success in extending Russia, their benefits, and their risks and costs,” it continues.

The report adds: “Imposing deeper trade and financial sanctions would also likely degrade the Russian economy, especially if such sanctions are comprehensive and multilateral… Encouraging the emigration from Russia of skilled labor and well-educated youth has few costs or risks and could help the United States and other receiving countries and hurt Russia, but any effects—both positive for receiving countries and negative for Russia—would be difficult to notice except over a very long period…”

And then it continues: “Providing lethal aid to Ukraine would exploit Russia’s greatest point of external vulnerability. But any increase in U.S. military arms and advice to Ukraine would need to be carefully calibrated to increase the costs to Russia of sustaining its existing commitment without provoking a much wider conflict in which Russia, by reason of proximity, would have significant advantages.”

And this is how the Rand Corporation report ends:

Conclusions

“The most-promising options to ‘extend Russia’ are those that directly address its vulnerabilities, anxieties, and strengths, exploiting areas of weakness while undermining Russia’s current advantages. In that regard, Russia’s greatest vulnerability, in any competition with the United States, is its economy, which is comparatively small and highly dependent on energy exports. Russian leadership’s greatest anxiety stems from the stability and durability of the regime, and Russia’s greatest strengths are in the military and info-war realms (…)

“Most of the options discussed, including those listed here, are in some sense escalatory, and most would likely prompt some Russian counter escalation. Thus, besides the specific risks associated with each option, there is additional risk attached to a generally intensified competition with a nuclear-armed adversary to consider. This means that every option must be deliberately planned and carefully calibrated to achieve the desired effect.

“Finally, although Russia will bear the cost of this increased competition less easily than the United States will, both sides will have to divert national resources from other purposes. Extending Russia for its own sake is not a sufficient basis in most cases to consider the options discussed here. Rather, the options must be considered in the broader context of national policy based on defense, deterrence, and—where U.S. and Russian interests align—cooperation.”

***

Question: Did America’s policy-makers carry out a full and transparent public debate on “providing lethal aid to Ukraine” in order “to exploit Russia’s greatest point of external vulnerability” prior to sending this aid?

This report openly recognizes that, if this policy is carried out, there might be a risk of a wider war: “any increase in U.S. military arms and advice to Ukraine would need to be carefully calibrated to increase the costs to Russia of sustaining its existing commitment without provoking a much wider conflict.”

An old chaos of the sun…

In the 8th and final stanza of his haunting 1915 poem Sunday Morning— which was, appropriately, written during World War I; the title could refer to any Sunday morning, or could have a connotation of that Sunday morning which was the first Easter morning — the American poet Wallace Stevens wrote these lines:

She [an ordinary woman on an ordinary Sunday morning, sitting by quiet water, not attending church, but reflecting on faith and on life, and the possibility of eternal life] hears, upon that water without sound,

A voice that cries, “The tomb in Palestine

Is not the porch of spirits lingering.

It is the grave of Jesus, where he lay.”

We live in an old chaos of the sun,

Or old dependency of day and night,

Or island solitude, unsponsored, free,

Of that wide water, inescapable.

Deer walk upon our mountains, and the quail

Whistle about us their spontaneous cries;

Sweet berries ripen in the wilderness;

And, in the isolation of the sky,

At evening, casual flocks of pigeons make

Ambiguous undulations as they sink,

Downward to darkness, on extended wings.

(end of poem)

Critic Austin Allen writes: “Wallace Stevens’s “Sunday Morning” (1915) is a lofty poetic meditation—almost a philosophical discourse—rooted in a few basic questions: What happens to us when we die? Can we believe seriously in an afterlife? If we can’t, what comfort can we take in the only life we get? As World War I intensified and Stevens neared middle age, he broached these subjects with quiet urgency in a poem as beautiful as it is difficult.” (link)

Stevens was not a Christian believer. But he struggled with the consequences of his choice.

We too struggle with our choice.

We now observe our world on the brink of fateful decisions, and pray that human goodness and common sense may overcome the deep-rooted passions of men to dominate and destroy.

Meanwhile, we are grateful for these peaceful days:

Deer walk upon our mountains, and the quail

Whistle about us their spontaneous cries…

***

Maria, ora pro nobis. (“Mary, pray for us.”)

Excerpts from the Rand Corporation report on “Overextending and Unbalancing Russia.”

Overextending and Unbalancing Russia (link)

Assessing the Impact of Cost-Imposing Options

April 24, 2019

by James Dobbins, Raphael S. Cohen, Nathan Chandler, Bryan Frederick, Edward Geist, Paul DeLuca, Forrest E. Morgan, Howard J. Shatz, Brent Williams

This brief summarizes a report that comprehensively examines nonviolent, cost-imposing options that the United States and its allies could pursue across economic, political, and military areas to stress—overextend and unbalance—Russia’s economy and armed forces and the regime’s political standing at home and abroad. Some of the options examined are clearly more promising than others, but any would need to be evaluated in terms of the overall U.S. strategy for dealing with Russia, which neither the report nor this brief has attempted to do.

The maxim that “Russia is never so strong nor so weak as it appears” remains as true in the current century as it was in the 19th and 20th.

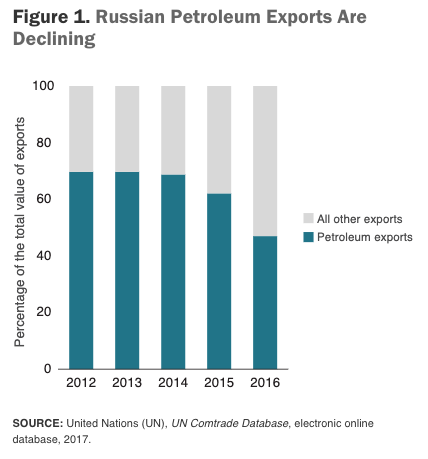

Today’s Russia suffers from many vulnerabilities—oil and gas prices well below peak that have caused a drop in living standards, economic sanctions that have furthered that decline, an aging and soon-to-be-declining population, and increasing authoritarianism under Vladimir Putin’s now-continued rule. Such vulnerabilities are coupled with deep-seated (if exaggerated) anxieties about the possibility of Western-inspired regime change, loss of great power status, and even military attack.

Despite these vulnerabilities and anxieties, Russia remains a powerful country that still manages to be a U.S. peer competitor in a few key domains. Recognizing that some level of competition with Russia is inevitable, RAND researchers conducted a qualitative assessment of “cost-imposing options” that could unbalance and overextend Russia. Such cost-imposing options could place new burdens on Russia, ideally heavier burdens than would be imposed on the United States for pursuing those options.

The work builds on the concept of long-term strategic competition developed during the Cold War, some of which originated at RAND. A seminal 1972 RAND report posited that the United States needed to shift its strategic thinking away from trying to stay ahead of the Soviet Union in all dimensions and toward trying to control the competition and channel it into areas of U.S. advantage. If this shift could be made successfully, the report concluded, the United States could prompt the Soviet Union to shift its limited resources into areas that posed less of a threat.

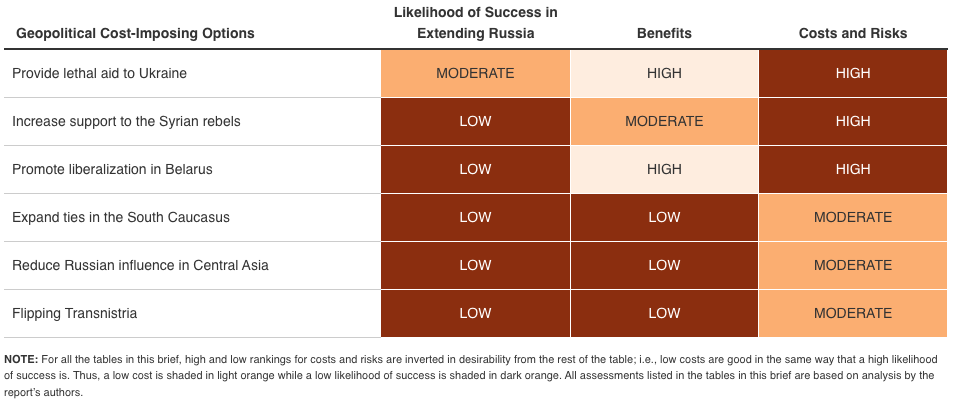

The new report applies this concept to today’s Russia. A team of RAND experts developed economic, geopolitical, ideological, informational, and military options and qualitatively assessed them in terms of their likelihood of success in extending Russia, their benefits, and their risks and costs.

Economic Cost-Imposing Measures

Expanding U.S. energy production would stress Russia’s economy, potentially constraining its government budget and, by extension, its defense spending. By adopting policies that expand world supply and depress global prices, the United States can limit Russian revenue. Doing so entails little cost or risk, produces second-order benefits for the U.S. economy, and does not need multilateral endorsement.

Imposing deeper trade and financial sanctions would also likely degrade the Russian economy, especially if such sanctions are comprehensive and multilateral. Thus, their effectiveness will depend on the willingness of other countries to join in such a process. But sanctions come with costs and, depending on their severity, considerable risks.

Increasing Europe’s ability to import gas from suppliers other than Russia could economically extend Russia and buffer Europe against Russian energy coercion. Europe is slowly moving in this direction by building regasification plants for liquefied natural gas (LNG). But to be truly effective, this option would need global LNG markets to become more flexible than they already are and would need LNG to become more price-competitive with Russian gas.

Encouraging the emigration from Russia of skilled labor and well-educated youth has few costs or risks and could help the United States and other receiving countries and hurt Russia, but any effects—both positive for receiving countries and negative for Russia—would be difficult to notice except over a very long period. This option also has a low likelihood of extending Russia.

(…)

Geopolitical Cost-Imposing Measures

Syrian Democratic Forces trainees, representing an equal number of Arab and Kurdish volunteers, stand in formation at their graduation ceremony in northern Syria, August 9, 2017. Photo by Sgt. Mitchell Ryan/DoD

Providing lethal aid to Ukraine would exploit Russia’s greatest point of external vulnerability. But any increase in U.S. military arms and advice to Ukraine would need to be carefully calibrated to increase the costs to Russia of sustaining its existing commitment without provoking a much wider conflict in which Russia, by reason of proximity, would have significant advantages.

Increasing support to the Syrian rebels could jeopardize other U.S. policy priorities, such as combating radical Islamic terrorism, and could risk further destabilizing the entire region. Furthermore, this option might not even be feasible, given the radicalization, fragmentation, and decline of the Syrian opposition.

Promoting liberalization in Belarus likely would not succeed and could provoke a strong Russian response, one that would result in a general deterioration of the security environment in Europe and a setback for U.S. policy.

Expanding ties in the South Caucasus—competing economically with Russia—would be difficult because of geography and history.

Reducing Russian influence in Central Asia would be very difficult and could prove costly. Increased engagement is unlikely to extend Russia much economically and likely to be disproportionately costly for the United States.

Flip Transnistria and expel the Russian troops from the region would be a blow to Russian prestige, but it would also save Moscow money and quite possibly impose additional costs on the United States and its allies.

(…)

Encouraging domestic protests and other nonviolent resistance would focus on distracting or destabilizing the Russian regime and reducing the likelihood that it would pursue aggressive actions abroad, but the risks are high and it would be difficult for Western governments to directly increase the incidence or intensity of anti-regime activities in Russia.

Undermining Russia’s image abroad would focus on diminishing Russian standing and influence, thus undercutting regime claims of restoring Russia to its former glory. Further sanctions, the removal of Russia from non-UN international forums, and boycotting such events as the World Cup could be implemented by Western states and would damage Russian prestige. But the extent to which these steps would damage Russian domestic stability is uncertain.

While none of these measures has a high probability of success, any or all of them would prey on the Russian regime’s deepest anxieties and might be employed as a deterrent threat to diminish Russia’s active disinformation and subversion campaigns abroad.

To continue reading this report, click here.

[End, excerpts from Rand report on “Overextending and Unbalancing Russia”]

Facebook Comments