“Like a flower he comes forth and withers. He flees like a shadow and does not remain.” —Job 14:2

“A voice called out: ‘Cry.’ And I said: ‘What shall I cry?’ ‘All flesh is grass, and all the glory thereof as the flower of the field.’ The grass withers and the flowers fall when the breath of the Lord blows on them”—Isaiah, 40:6-7

“I will deliver them out of the hand of death. I will redeem them from death: O death, I will be thy death.” —Hosea 13:14

“O Death, where is thy victory? O Death, where is thy sting?”—St. Paul, First Letter to the Corinthians, 15:55-56

“Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither hath it entered into the heart of man, what things God hath prepared for them that love him.” —St. Paul, First Epistle to the Corinthians, Chapter 2:9-10

“Behold, I tell you a mystery. We shall all indeed rise again.” —St. Paul, Ibid., Chapter 15:51

“For He will transform the body of our humiliation into the image of His glorious body, according to His great power, by which all things been made subject to Him.” —Philippians 3:21

My Father’s Passing

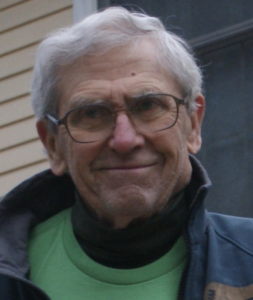

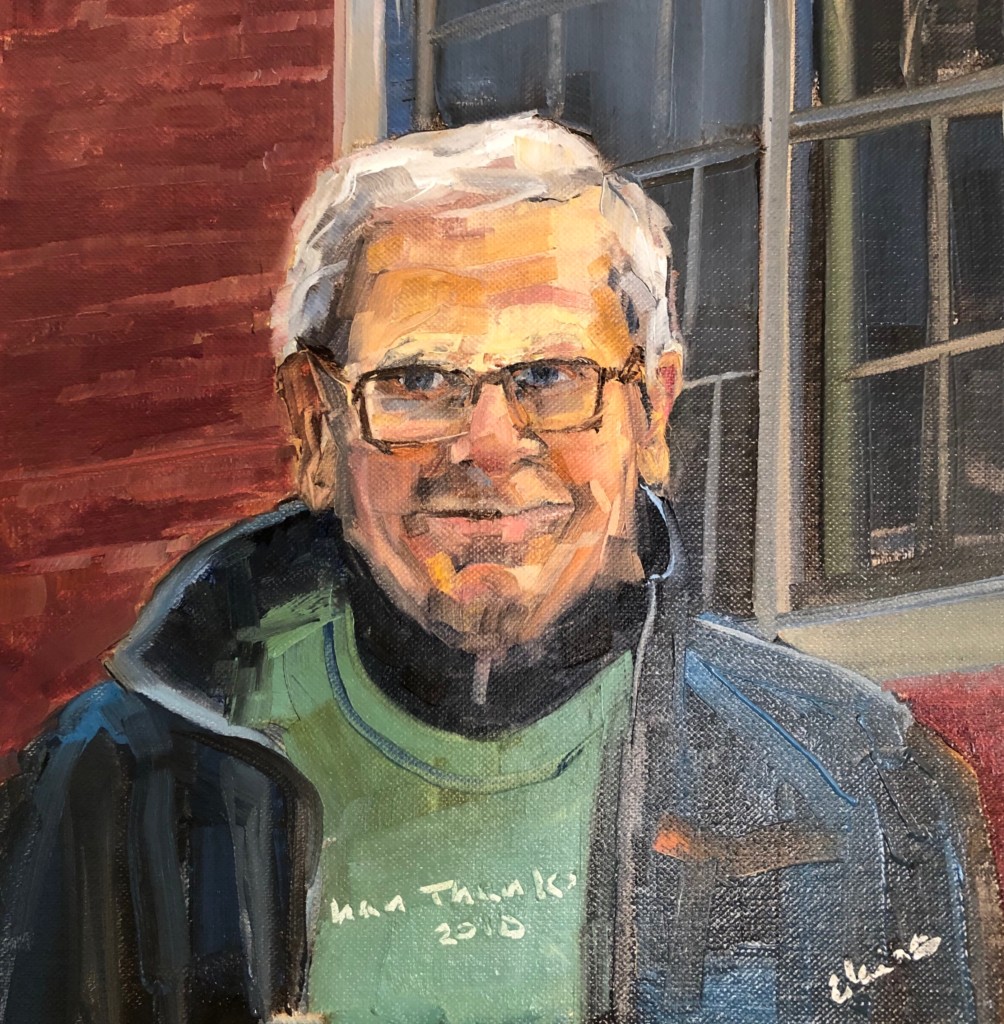

My father, William Moynihan, passed away on Saturday morning, March 28, two days ago, just before dawn, peacefully, at his home in Connecticut.

I do not know if the Coronavirus had any role in his death. He was not tested for the virus. Toward the end, he did have a spiking fever which reflected an internal infection. But I did not expect his death so soon.

Due to quarantines and restrictions on travel, I was not able to be with him (I left Italy before travel restrictions locked the country down, but did not go to see him in my childhood home in Connecticut to avoid any chance that I might carry the virus with me and infect him; I do not have any symptoms and I think I am well).

I will not be present tomorrow for the Rite of Christian Burial when my father is buried next to my mother. Only five people are allowed to gather at one time and place in Connecticut today. So the local priest will commend my father to God, and also present will be someone from the local funeral home, two of my brothers, and one of my sisters.

This email, then, must become my farewell to my father, in such a time.

I will not go on very long.

My father gave me life, shaped my character, mind, and thought. He guided me, did not abuse or harm me, allowed me to be myself while always encouraging me to be the best that I could be.

He always said to me, “Take the high road.”

He was the grandson of an Irish immigrant who came to Haverhill, Massachusetts in about 1870. For such Irish immigrants, the Catholic parish was a second home — and sometimes, a first home. The Church meant so much to them. It indicated to them that “higher road” my father urged me to walk in life.

When I was four or five, he handed me an old Catholic missal he had thumbed through in minor seminary (yes, he studied to become a priest; if he had continued, I would not be here). “This is the most important book you will ever own,” he said, to my wide eyes.

The missal’s pages were fine as gossamer, transparent, so thin that turning them was a marvel — the paper was so thin I thought it might tear, but so strong it never tore.

In that thick missal, with its various colored threads to mark places, were the prayers of the Church: the Mass, the daily office, and all of it both in Latin, and in English. So I felt from earliest childhood that I was poised between a culture of “now” and a culture of “always.” Between a way of using words (in English) that my playground friends and I could share with ease, and a way of using words which none of us could use with ease, but which rolled down the centuries like a sonorous tolling bell, telling me each week, each day, “we are one people, one tradition, from the apostles until today, via a cloud of witnesses whose names we chant: Linus, Cletus, Clement, Sixtus, Cornelius, Cyprian, Lawrence, Chrysogonus, John and Paul, Cosmas and Damian.” That I felt from the age of five. That my father gave me.

There would be a time to say much more. He helped me when I started the magazine in 1993, writing many beautiful, thoughtful articles, and without him perhaps the magazine would not have survived — he also helped me financially. He thought and wrote clearly. He urged me to think and write clearly. I owe him so much, beyond what can be written.

But for this day, I want to remember one thing he wrote for me that I never read until a few weeks ago, when my sister found the passage in my father’s diary. It was the entry for the day of my birth.

“Thursday, November 12, Robert Barnes Moynihan born 4 a.m. this day at Meriden hospital. Dr. Pennington delivering. Mother fine.

“Dear Robert, welcome to existence. I fear you will be exposed to the eternal struggle for eternal life in much the way your father was. Instead of learning from my mistakes, I hope you learn from my virtues. Don’t question for an instant the nature of this existence — it is struggle — a testing. For what purpose? No man knows for sure, but if you look closely and sympathetically you will see that a meter and rhyme so closely intermingles both the human (animal) and divine that you know eternity is a phase of life yet to be had. God love, protect and bless you. Maria, ora pro nobis.”

I did not know my father had written such words to me. I did not know that he had invoked God’s protection and blessing and Mary’s prayer on my life and on his life and my mother’s life — “Mary, pray for us,” for us, not “Mary, pray for him,” but “for us,” for me in communion with them, my parents, and with the six brothers and sisters who were to follow.

This father, my father — like so many of your fathers — was the source and model of all my thought. The question of fatherhood is a core question. What does it mean to be a father? How does one generate, and nourish, and guide, and chastise, and then step aside, from a son or daughter? How do we generate human beings with fragile yet eternal souls, and care for them, as long as time permits? How are the fathers in the Church (the priests) truly fathers? How is the Pope, the papa, as the Italians call him, a true father? How does one balance one’s filial piety and duty to honor one’s father with one’s duty to encourage and even strengthen one’s father? What does it mean to be a true son? Jesus asked his heavenly father to “let this cup pass from me.” But he also assented to the father’s will: “yet not my will, but thy will be done.”

Below I include two poems my father wrote, poems I never read until this weekend, after my father’s death.

Dad, may eternal light shine upon you, and may you rest in peace.

Poems by My Father

In these two poems, my father is reflecting on his own father, Richard Moynihan, and for this reason, it seemed fitting to me to include these two poems here, in the moment that I am reflecting on his life and death. Richard Moynihan, a strong man, who was a police officer in Haverhill Massachusetts, in the 1930s, died fairly young, of stomach cancer, at the age of 64, painfully.

In the first poem, my father says his deceased father sometimes comes to sit by him, as he sits reading on the sofa in the evening. I know that sofa well. It is still there today, almost 60 years later, and in my mind’s eye I see him still sitting there, reading, and, as he says, sitting alongside his father.

The “Stephen” he refers to is Stephen Dedalus, the name that the great Irish writer James Joyce gave himself in his fictionalized account of his own upbringing, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Stephen is sent to boarding school at Clongowes Wood College (a Jesuit school). There he suffers from bullying and shyness and from actual physical illness. He seems to have few friends. He tries to figure out his place in the world, and fails. So it seems my father had been reading that passage when he wrote this poem.

He also mentions Keats, who is John Keats, the great British poet, who died young in 1821. His death occurred, actually, in Rome. Travelers can still see the house where Keats died, of tuberculosis, when he was just 25 years old, next to the bottom of the Spanish Steps in Piazza Spagna, just to the right looking up from the bottom. Keats wrote so beautifully that his words seemed chiseled in the air, and his early death meant that he never passed through middle and old age, he was “always young.” But also, Keats died so young that we have fewer of his works than we might have had, had he lived, and so Keats is always for writers who hesitate and delay their artistic projects a type, at once, of spur… and warning.

Then my father speaks of his love for his children. He says we are all sleeping upstairs, so it must have been late in the evening, perhaps 11 o’clock, perhaps even midnight. There were in 1965 seven of us. I was the oldest, at age 11, then my sister Elaine at 10, my brother Ted at 8, my brother Neil at 5 or 6, my sister Sue at 4, my brother Rich at just 2, and my youngest brother, Benjamin, at 1. He says he wishes he could go up the stairs and hug each one of us. And that is how I remember him, hugging us, and then sending us out into the world. “Go with God,” he would say, every time. And he says he wishes he could speak “with the passion of boyhood,” so we understand that he felt the height of his passion was when he was young, and his father was still alive, and they were together. And so we understand that he is saying that he loves his children as he loved his father, who was filled with life, and now has passed away. So these are the emotions he is feeling as he writes this poem.

I love particularly the final verses, “And oh, how I love them such nights when my far father sits with me here, alone and reading.” I love the words “my far father.” I had never read this poem before, and now my father is what he calls his own father in this poem: “my far father.” He was with me so often, and now he is far. And yet, my father still sits with his father, as he recounts to us in this poem, and so I still sit with my own “far father” as I write these poor words, two days after his passing.

Alone and Reading

By William T. Moynihan (1926-2020)

Sometimes late at night he sits by me

When I am alone and reading

(It could be of Stephen at Clongowes

Or of Keats who was always young)

And I think of my own children

Who are sleeping overhead, and I want

To climb the stairs and grasp them

One by one, my eyes and arms loud

With fear, shouting to each with the passion

Of boyhood: I love you like life,

Sad and young, that is dead. And oh

How I love them such nights when my far father

Sits with me here, alone and reading.

(written in 1965, age 39)

In this poem, my father, at age 30, writes of his own father’s death: “I sit and watch an old man die.” He is deeply troubled “my past and future unraveling.” He conflates his own unraveling certainty about his life with a vision of his father in his prime who “loud as a circus lion / walked huge and sure above the grass.” We know that he saw his father thus, in his memory, as he had been, either literally or figuratively, “fresh washed and green stained.” So he is capturing an image from childhood, of sitting on the grass, and seeing his father walking toward him, or past him, “huge and sure” and “timeless as a flowing falcon.” He remembers visiting sports events with his father, perhaps football games, with runs and thuds and throws and tackles. My father’s older brother, Richard — Uncle Dick to me — a strong, large youth, was a star football player at St. James High in Haverhill, in the 1930s. So father and son most likely watched with great intensity as the older son, the older brother, played on those green fields.

He cannot grasp that his strong, proud father has been reduced to this. He feels, I think, “joy and pain” because he is joyful that they can still be together even in this moment, but in pain because he knows his father is departing forever. He writes: “Now my high noon love / pierces the silences of your dying.” He says “high noon,” because he is, at age 30, at the “high noon” of his life. It also means that it is the “high noon” of his love, that he has never loved his father more intensely and completely. Since he writes “pierces the silences,” I imagine either he is sobbing loudly, or speaking, “Dad, I love you.” He accurately describes his father: “flailing your thin blue bones / in a fury of helplessness.” My father flailed so, in such a fury, hours before the end, when he couldn’t control anything, and felt great pain in his scoliated back, and could not roll to one side to ease the pain, and whispered, gesturing feebly, “Help me, help me.”

He speaks of his father’s “restless sleep” and my father too slept fitfully, telling us he saw his father coming into the room, and his beloved wife, Ruth, my mother, who passed away on October 1, 2018, a year and a half ago. The caretakers said, “He has hallucinations.”

But I disagreed. I think his father and beloved wife of 65 years were coming to be with him in his pain, for this last journey.

Our parish priest, Fr. John Antonelle, of St. Thomas Aquinas Church in Storrs, Connecticut, was not afraid of the Coronavirus, and came to our house, to my father’s bedside, and anointed him, and gave him the last rites, and my father saw and understood, and nodded, and fell into his last deep sleep — just as his own father had done, in this poem. “In your restless sleep / I heard you pray… purchasing the past eternally.”

I think he means, asking forgiveness for all his indiscretions, faults and sins, and in this way “purchasing his past” as he prepared for eternity.

The poem ends with four difficult lines, which seem to conflate birth and death, death and birth, as death (from stomach cancer) is compared to a “devouring embryo” which “devours your flesh” and is said to be “hatefully hastening the blessed April” — the time of his father’s death — the time when the source (“my seed”) of his own life, his father, will be “consumed in earth.”

My father was a man. He was not perfect. He may have misjudged, caused offense, fought with temptation. But he lived “in the light of God,” and “under the aspect of eternity.” All my life he told me that, from the perspective of the world, the faith is folly, while from the perspective of the disciples, it is God’s surpassing glory, beyond what we can imagine, with our rational minds. This world tests us, even — I dare to say — enslaves us, in many ways, many different ways. In fact, we enslave ourselves.

So our freedom must come from an infusion of power which surpasses us, and heals us, and sets us free. This, my father taught me.

I recall, as a boy, that he would kneel with his head in his hands after communion. “Why does he sit with his head in his hands?” I wondered. He sat with his head in his hands to be a witness to being a man, so that I, and others, could see. Yes, he “walked huge and sure upon the grass,” but he also knelt and bowed his head. And in that gesture, I understood that he was in relation with some principle, some reality, some ground of being, some holy and hidden God, who drew him toward Himself. That was the lesson my father gave to me. Not to tick off the boxes of a pre-fabricated life, but to get up and walk on a journey toward the infinite, even after falling down, especially after falling down, and continuing to the end, for in our end is… our beginning.

My father has now truly begun.

And I rejoice for that, though my tears flow down.

He asked me to do one last thing, before the end: “Write,” he said. “Write your book. Finish it for me. Don’t get it right, get it written!”

And so now, as I sit here writing, my far father still sits here across from me, and I seem to see him smile, and hear him say: “Take heart. Get up and begin again. The journey is not yet done, the day still has sufficient light for you to do something that needs to be done.”

Elegy

By W. T. Moynihan, 21 L’Homme Street, Danielson, Connecticut, USA (1926-2020)

I sit and watch an old man die

My past and future unraveling

Which once loud as a circus lion

Walked huge and sure above the grass

Where I sat fresh washed and green stained.

Timeless as a flowing falcon

You watched with me in the long afternoons

Of athletes whose gains and losses

Foreshadowed this absolute joy and pain.

Now my high noon love pierces the silences

Of your dying, flailing your thin blue bones

In a fury of helplessness.

In your restless sleep I hear you pray

Among strange streets and unknown names

Purchasing the past eternally

While the fatal devouring embryo grows

In you, devouring your flesh

And hatefully hastening the blessed April

Which will consume my seed in earth.

—(written in 1956 or 1957, when he was 30, after his father’s death in early April of 1956)

Facebook Comments