Italian historian Alberto Melloni. He has written a book on the history of papal conclaves (link). Now he is calling on Pope Francis to change the rules of the next papal conclave… in order to avoid a possible division among the cardinals, and a division in the Church after the conclave… Melloni teaches History of Christianity at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, and heads the John XXIII Foundation for Religious Sciences in Bologna, Italy

Letter #6, 2024, Monday, March 4: Melloni on conclaves

A leading Italian historian of papal conclaves fears that the current rules of papal conclaves leave the Church open to a possible catastrophe.

For this reason, Melloni is urging Pope Francis to make reforms to the voting procedure designed to move much more slowly, lengthening the conclave process in order to “vet” potential candidates before electing them only to find there is some “skeleton” in the new Pope’s closet.

“Here is a scenario from an imaginary future conclave,” Melloni wrote in The Tablet almost three years ago (link). “White smoke from the chimney above the Sistine Chapel; the cardinal protodeacon appears on the balcony of St Peter’s to declare Habemus papam [“We have a Pope”]; the purple mozzettas crowd around the side windows; the newly elected pope steps out. And as he smiles and humbly introduces himself to the crowds in the square, a lone social media post makes a stunning allegation. Within seconds, the story is across the internet: the elected cardinal, when he was bishop, had received a hypothetically credible complaint of an abuse committed by a priest and had waited, or waited too long, before acting. The accused priest had gone on to commit further crimes. In the square and in the press boxes, eyes drop from the balcony to their smartphones. Enthusiasm gives way to embarrassed silence. The pope steps back inside, and resigns. The see is again vacant.“

So, it seems, Melloni is concerned about the “global reach” of our “information culture” — and those who own or control the means of that culture — which registers a huge number of events and actions, text messages and emails, in a way that was unthinkable just a few years ago.

And because Melloni thinks a Pope might be elected with insufficient knowledge about all of the decisions he has made in his life, only to have those decisions made public moments after his election, he is calling on Pope Francis to “slow down” the process of electing Popes.

Rather than have four votes each day, he is proposing one vote only per day.

And then, rather than having a vote every day, he is proposing (possibly) voting… only once every other day…

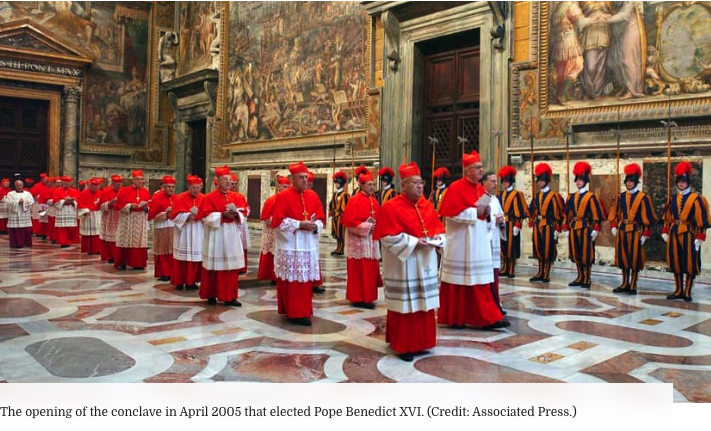

Thus, for example, a conclave with a failed vote on the 1st day followed by an election on the 4th ballot of the second day — as occurred in 2005 when Pope Benedict was elected — could take, under Melloni’s proposal, not two days, but 10 full days(!)…

So the main thrust of Melloni’s argument is to slow down the conclave, and, evidently, check even more carefully than ever before to see if there is anything in the past of a newly-elected Pope which might cause scandal and confusion in the world and in the Church.

The suggestion seems to be that the cardinals would be informed if there might be such an accusation against the newly-elected Pope to ensure that the college would remain steadfast and united even if such an accusation were suddenly made.

Here below is an article about Melloni’s proposal from Crux, and the article by Melloni himself, published in Italian on February 26 in Il Mulino in Italy, in our own, sometimes imperfect, English translation. —RM

The February 29 article from Crux:

Pope supporter argues for a slower conclave to face risk of smear campaigns (link)

By Crux Staff

Feb 29, 2024

ROME – A prominent progressive supporter of Pope Francis has suggested changes to the rules governing conclaves to slow down the election of the next pope, in order to guard against the possibility that well-timed leaks or other forms of interference, perhaps related to charges of sexual abuse, might influence the outcome.

Specifically, veteran Italian Church historian Alberto Melloni has proposed that there be only one ballot each day the cardinals are gathered in the Sistine Chapel to select a new pope, followed by a day of pause for conversation and reflection.

Melloni also called for the eventual acceptance of the election result to be slowed down as well, giving a candidate who receives more than two-thirds of the vote, and thus who’s elected as pope, a full night to consider and to consult before making a final decision.

Under such a system, Melloni noted, the conclave of 2005, which required just four ballots and roughly 24 hours to elect Pope Benedict XVI, would have lasted ten full days instead.

Melloni is best-known as a key figure in the “Bologna school” associated with the late historian Giuseppe Alberigo, which produced a multi-volume history of Vatican II (1962-65) that popularized a progressive reading of the council.

His essay on the conclave appeared Feb. 26 as part of the online edition of Il Mulino (“The Mill”), a popular Italian journal of culture and politics.

In effect, Melloni argues that current events, including the Russian war in Ukraine and the Israeli/Hamas conflict in Gaza, offer reminders that there are forces on the world stage seeking some form of either regional or global hegemony – and that the Catholic Church, as he puts it, is a “natural antagonist and objective obstacle” to such ambitions.

For all its faults, Melloni argues, the Catholic Church is a uniquely unarmed but nevertheless powerful global institution, which various states and non-state actors might wish to influence or subvert.

In that context, Melloni says, the clerical sexual abuse scandals have created “a button with which anyone can ostracize anyone else, leaving it to history to sort out justified accusations from the unjustified, and to God to compensate the innocent and punish the guilty.”

For that reason, Melloni suggests, the next conclave “will have to protect the elected person from the risk of being delegitimized by an accusation designed to divide cardinals who challenge the election of an unworthy person from those who instead consider the election valid, at least for the presumption of innocence.”

Historically, Melloni argues, the function of a conclave has not been to ensure that the holiest or most qualified person is elected pope, but simply to guarantee that the outcome would be considered legitimate and the authority of the new pope accepted.

In an age of artificial intelligence, social media and mass computing power, Melloni writes, that function faces new threats related to the capacity to circulate damaging accusations against public figures on a mass scale and in real time.

Doing so with regard to the abuse scandals, Melloni says, is merely a question of “will and means,” both of which “can arise within states, or in those large companies that act like superpowers of computing and which can place their megalomaniac servility at the service of occult powers, as we’ve already seen in various public affairs.”

To remain compactly behind the newly elected pope even in the teeth of such an attack, Melloni writes, will require a compact and united College of Cardinals truly certain of its choice, for which more time may be required.

Lengthening the conclave, he argues, “would guarantee time for conversation and discussion within the college, which is more necessary than ever to reach a more shared electoral process and to allow candidates time to withdraw, in the well-founded expectation that someone could use true or even plausible information against them.”

A slower process, Melloni says, would also counteract “the media tendency to paint a conclave with the colors of an American primary, made up of tricks, money and ideological maneuvers.”

Moreover, Melloni also says that the custom of holding two ballots back-to-back inside the conclave was designed to replace the older custom of “accession,” in which a cardinal could change his vote after a ballot in which no one received a two-thirds majority. The system was cumbersome and also compromised the secrecy of the first vote, since ballots had to be checked to ensure that a cardinal wasn’t voting for the same candidate twice. The option was suppressed in 1903.

As to whether Pope Francis might adopt such a reform, Melloni says “probably yes,” despite voicing concern that the advisors on Church law to whom the pontiff might entrust such a project lack both the “ecclesiological talent” and “legal virtuosity” of earlier generations of canonists.

Nonetheless, Melloni argues, a reform is necessary to avoid the risk that “warring nations and the great players in the media market” might subvert the conclave, provoking a “fatal impasse in the unity of the Church.”

The February 29 article from Il Mulino:

MAKE THE CONCLAVE SLOWER (link)

A reform of the conclave, albeit small, which does not alter its composition, functions, majorities, but extends its time would be very necessary. For multiple reasons

“The extraordinarily short duration of the two conclaves of 2005 and 2013 says that a college of cardinals without internal connections has a tendency to surrender quite quickly to the candidate who rises most rapidly.”

February 26, 2024

In December 2023, two pieces of news were launched from one of the American sites dedicated to the denigration of Pope Francis.

The first was that the pontiff had asked that work to carry out a reform of the conclave process begin. Rather than news, it was non-news, since the maintenance of the institution of the conclave over the centuries has been normal, and over the last two centuries almost constant — a guarantee that no one could challenge the election by complaining about the obsolescence of the rules.

The second piece of “news” was that the Pope was considering including in the conclave (as he did in the synod of bishops) other non-cardinal figures to increase the “representativeness” of the electoral body: an innovation that would mean the abandonment of the Gregorian rule which since 1049 has reserved the election of the bishop of Rome to those clergy of Rome who were cardinals, thus transforming the choice of Peter’s successor into the casting for a Father General or the CEO of a Catholic multinational corporation — roles which do not exist.

Nothing has come of these rumored reforms between then and now.

The tidal wave caused by Fiducia supplicans — the instruction of the Doctrine of the Faith on the blessing of “irregular” couples which will go down in the annals as useless (those who did it will continue, those who are hostile will deny it), ineffective (if the objective was to silence the debate in the German Synod this was missed), counterproductive (the description of love between people of the same sex provided in that act is more acrimonious and unfair than that of the Catechism) and vulgar (the recommendation to contain it in 15 seconds which is a sixth of that dedicated to (the blessing of) a stable) – suggests that, even if the ecclesiological superficiality of some of the pope’s advisors had entertained the idea (of changing the conclave rules), it is not in these months of 2024 that the conclave will be able to be replaced with another institution.

Yet — it is an opinion that I have already expressed in The Tablet and on the print edition of this magazine — a reform of the conclave that alters not its composition, functions, majorities, but its timing would be very necessary for reasons that are evident to money, not only to the most attentive observers.

The return (today) of the wars waged, directly or by proxy, by the superpowers of the 20th century – the Russian invasion of Ukraine after eight years of war, the Hamas pogrom in Israel, followed by an operation conducted by the Israeli Defense Forces with a frightening number of civilian victims that Hamas transforms into recruitment propaganda – has reminded everyone of an often forgotten trait of Roman Catholicism.

And that is that, in a world in which ambitions for hegemony on both a regional and global scale are becoming increasingly evident, the Roman Catholic Church, more and more massively than other Churches or communities of faith, constitutes a natural antagonist and an objective obstacle to neo-imperialist sovereignism.

In the face of power policies based on atomic and technological deterrence, the Church of Rome represents a reality that is disarmed but global by nature, with a grip that, although reduced by the processes of secularization and not yet adapted to post-secular society, remains incomparable in quantitative and qualitative terms compared to other universes, such as the Sunni one, in which terrorist impulses have taken root which require very long eradication times and theological elaborations of cohesion which are still just embryonic today.

In the long struggle between modernity and the papacy understood as the summit of a lost Christianity, the Roman Catholic institutions had developed their own culture of the enemy, made up of condemnations, anathemas, excommunications, social and dogmatic doctrines that have long made sterile and supplanted the powerful and simple announcement of the Gospel.

But once that era was over — due to the consumption of modernity as an expansive ideology and reform of the papacy thanks to the Second Vatican Council and its reception — the Church of Rome did not dedicate much attention to building the systems to defend, no longer its own temporal power or to affirm the nostalgia of an imaginary Christianitas [“Christendom”], but to defend its own institutional physiognomy.

Even if what emerges from the 20th century is not the “servant and poor” Church dreamed of by Marie-Dominique Chenu, it has certainly abandoned the moral haughtiness of Catholic triumphalism — which was not the brake, but the incubator of the most reckless financial associations and of the most devastating silence towards the rate of rape of minors of which Catholic clerics have been guilty.

Yet, precisely the ecclesiastical legislation on what with a revealing euphemism is called “pedophilia” has created not a complex weapon, but a button with which anyone — the victims of unpunished violence, ecclesiastical authorities in ruthless competition, the most classic enemies of the Church – can obtain the ostracism of anyone, leaving to (the passage of) time the task of decanting well-founded or unfounded accusations, and to God to compensate the innocent and sanction the unpunished.

This is why a reform of the conclave is increasingly urgent and necessary: in fact, it does not take much imagination to understand that the college of cardinals will have to protect the elected person from the risk that he will be delegitimized by an accusation constructed to divide the cardinals between those who will challenge the election of an unworthy person from those who will instead consider the election valid, at least due to the presumption of innocence.

The conclave, in fact, in its historical journey, has an objective, which is not to elect the holiest, nor the most learned, nor even the most prudent (as required by the old monastic rule which recommended, concerning the choice of an abbot, that “si doctus doceat, si pius oret, si prudens regat” [“if he is learned, let him teach; if pious, let him pray; if prudent, let him rule”].

First the Gregorian reformers of the 11th century narrowed the base of electors to the cardinals, then the civil authorities forced them to remain in the city where they were elected from the middle of the 13th century — for the sole purpose of guaranteeing an uncontested and indisputable succession: despite the shortcomings of the beginnings and the disaster of the Western schism [from 1378 to 1417, when there were first two, then three popes at once], the institution of the conclave, therefore, continues to function precisely for this reason.

The same purpose is served by the custom which — after the incisive reforms of 1215, 1620 and 1903 — causes many popes to update the norms of the conclaves with the provisions and purposes I mentioned earlier. For the most part these are detailed adjustments to the calculation of the majority, but in addition to them there are also more relevant decisions such as the one which establishes that, regardless of the place in which the pope dies or resigns, the seat of the conclave remains the Sistine Chapel with the Last Judgment as the backdrop to the television footage preceding the extra omnes and the vote; more important, for our purposes, are the norms of Pius IX which make the election valid even in the case of simony: they, in fact, did not want to justify that crime, but to protect the conclave and the elected person from an accusation that the enemies of the time could have built or agitated to disarticulate the Petrine service in the Church.

Today that risk — with actors ultimately less sympathetic than the Garibaldians, Freemasons and Mazzinians who were greatly feared in the 19th century — is multiplied by social media, AI and computing power does not need long explanations.

Collecting the disappointment of the mother of a child violated by a cleric who attempted to unsuccessfully approach the future pope when he was bishop who knows where, or creating ex nihilo a case modeled on the many episodes in which the superficiality of bishops in the face of aggression has become negligence, negligence has become silence, and silence has become the heresy which defended an ecclesiastical “reason of state” which does not and cannot exist in Christianity, is a question of will and means; will and means that can arise within the States or in those large companies that act like superpowers of calculation [Note: he seems to be reffing to global communications and computer companies] and can put that megalomaniacal servility that we have seen at work in various public events at the service of even occult powers.

Is the conclave, an institution eight to ten centuries old, capable of defending the Church from a planned attack of this magnitude?

This is the doubt that the Pope knows well, and which he does not have an easy answer to.

Perhaps the conclave is not able to defend the Church in such a situation, if it concerns the election of a Churchman who does not even know that he has neglected a duty in ancient times; perhaps yes, if the college of cardinals, which swears loyalty to the newly elected pontiff, knew how to remain solidly united whatever happens and, to paraphrase Mario Draghi’s most famous maxim, “Whatever it takes: and believe me, it will be enough.”

With the current regulations, however, the risks multiply: the same extraordinarily short duration of the two conclaves of 2005 and 2013 (one lasted twenty-four hours, the other three hours more) says that a college of cardinals without internal connections ( of good or bad league) has the tendency to surrender quite soon to the candidate who grows more rapidly in the succession of the single evening vote on the first day and in the four ballots that follow one another from the next day, instilling in the cardinals the idea that a wait or a stalemate will be described by CNN “breaking news” as a “division” to be denied.

In 2005, for example, despite Bergoglio having achieved about a third of the votes, thus blocking the way for Joseph Ratzinger who showed up at lunch wearing a black turtleneck that spoke of his renunciation of the conclave “arm wrestling,” it was Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini who asked the German theologian to allow another vote and to persuade those who did not know Bergoglio to vote for the cardinal dean. In the first vote of the afternoon, Benedict XVI exceeded two thirds: total duration of the conclave, 24 hours. In 2013 the archbishop of Milan, Angelo Scola, received half the votes he thought he would have in the first vote: and the argument that someone who cannot distinguish between a sincere cardinal and a liar cannot be pope was fatal to him [to Scola], so that Cardinal Bergoglio was able to rise from the dozen votes on the first evening up to the abundant two thirds that made him Pope Francis: duration of the conclave, barely 27 hours.

Two different trends, but in any case they took place in a very short time in which the separation of the voters from the outside world certainly had no opportunity to become confidence, and from which the ascension of the bishop of Buenos Aires was already evident at 2:00 pm.

There is a simple and linear solution, and it would consist of a thinning out of the ballots: the second ballot in the morning and the second in the afternoon, in fact, have been introduced to replace the vote by access, which is too complicated to manage; removing it, and even perhaps also removing the morning vote or even leaving a “break day,”currently foreseen only in the event of a prolonged stalemate, after each day of voting, would guarantee a time for conversation and discussion within the college that is more necessary than ever to achieve to a more shared electoral specification and to give the candidates time to withdraw, in the well-founded expectation that someone could use true or plausible information against them.

A conclave with one vote a day and a day’s break could give rise to some irony about the pastimes of the cardinals, imagined by Nanni Moretti in his Habemus papam, but it would give time for opinions and moods to settle: in a conclave like the one in 2005 he would mean taking 10 days to reach a two-thirds majority, certainly decompressing the media tendency to describe the conclave with the colors of an American primary, made up of tricks, money and ideological constructs.

Finally, an extension of time would allow the acceptasne [Latin for “Do you accept” — the question asked of the candidate who receives the two-thirds vote to become Pope] to be split in two: in fact, when a poll ends in which a cardinal has exceeded two-thirds of the votes, he is publicly asked if he accepts the election held canonically (“acceptasne?”) and then the name; in a slow conclave the elected person could have longer time, even a night, to decide, and, if at all, consult.

Will Pope Francis carry out a reform?

Probably yes, for the reasons indicated.

How will he do it?

It’s difficult to say: the canonists to whom he entrusted very important reform acts do not seem to have the ecclesiological talent of Eugenio Corecco nor the legal virtuosity of Mario Francesco Pompedda.

But if nothing is done, we must hope that none of the belligerent countries and none of the big players in the news market tamper with a device that could resist or encounter, as it did in 1378, an impasse fatal to the unity of the Church.

[End, essay on revising conclave procedures by Alberto Melloni]

***

Final Note: You can follow us on our new Locals channel, recently launched and is now starting to grow, here. This is our new “community channel” on the internet. We started it because we wanted to have it ready in case there might be any problem with “de-platforming” (we did have some problems in the past). So, if you would like to support this letter, and also our developing podcast and internet efforts, you may make a donation here.

Facebook Comments