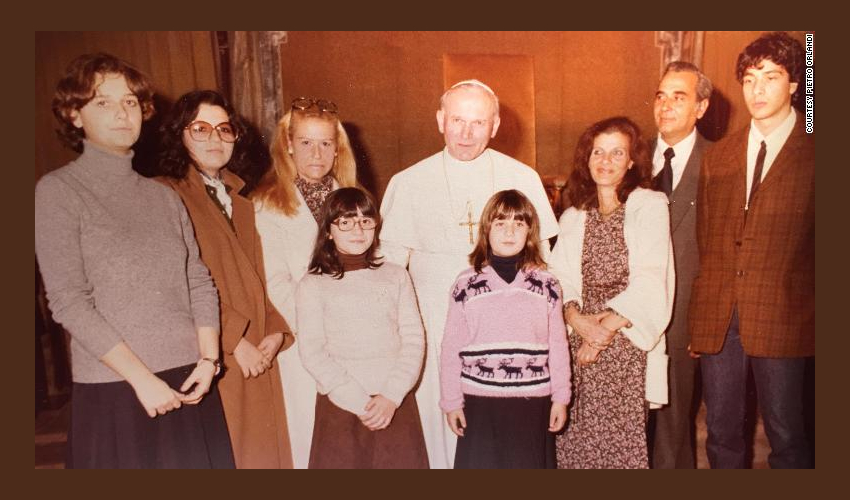

Emanuela Orlandi (in the pink sweater) with her family and Pope John Paul II at about age 11 in late 1978 of 1979, not long after Pope John Paul II was elected Pope (he was elected in October 1978). Four years later, on June 22, 1983, Emanuela would be kidnapped and never heard from again. Now, after 36 years, there are new elements emerging in the case. And those elements are being brought forth by…Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò

“It might have been on the night of June 23rd, not on the 22nd. But that there was a phone call followed by a fax is certain. And that fax must still be in the archives of the Secretariat of State.” —Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, this morning, speaking to me about the Emanuela Orlandi case, and about a phone call and a fax concerning the case that he says he received in the offices of the Secretariat of State in late June of 1983

The Tragic Case of Emanuela Orlandi

The case of Emanuela Orlandi is a tragic one, and has caused her family terrible, indescribable suffering.

So one hesitates to return to this case, after so many years — 36 years have now passed since she disappeared at the age of 15.

Emanuela walked out from Vatican City, where she lived with her family, to a music lesson at a music school across the Tiber River. She left the music lesson at about 6 p.m. on June 22, 1983.

Then, without warning, she was gone.

She was ever heard from again.

So I begin with an apology to her family members, who lost Emanuela on June 22, 1983, aware that bringing up this case once again may cause them suffering, renewing their sorrow for their loss.

A Late-Evening Phone Call in 1983

Emanuela Orlandi disappeared without a trace at about 6 p.m. on the evening of June 22, 1983.

Nothing more was ever heard from her.

In an interview on November 1, 2019 — five days ago — with prominent Italian Catholic journalist Aldo Maria Valli, Valli asked Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, 78, to tell the world what he recalled about “that evening of June 22, 1983” after Emanuela’s disappearance.

Viganò replied that he had received a phone call and fax that evening from Father Romeo Panciroli about the case, a report that said Emanuela had been abducted and that there were conditions being set for her release.

He received the call, and the fax, and handed the fax on to his superiors.

The story fell like a thunderbolt on the Italian press. (link, link, link)

But soon, a number of Italian journalists noted that Panciroli was not in Rome on the evening of June 22, 1983.

He was in Warsaw on a papal trip to Poland. He returned only the next day, on June 23, 1983.

And so these journalists suggested that the archbishop had, perhaps, “invented” the entire story out of whole cloth — just made it up.

See, in this regard, a November 5 piece by Tomasso Nelli, in Farodi Roma, entitled: “The strategy of poisonous attacks from Traditionalists continues: the Orlandi case: there were no telephone calls into the Vatican on the night of her disappearance. Also this time the ex-Nuncio Viganò is not credible.” (link)

Therefore, this morning, I called Viganò to ask him to set the record straight. Had he really received a phone call and fax from Fr. Panciroli related to the Emanuela Orlandi disappearance on the evening of June 22, 1983? Or, if the calls and fax had arrived, might he have mistaken the date, since Panciroli was in Warsaw, not in Rome, on the 22nd?

Viganò quickly acknowledged that he must have erred about the date of the phone call and fax from Fr. Panciroli.

It must not have been on June 22, he said, but (most likely) on the next day, June 23.

(My own note: We are speaking here of events 36 years ago.)

However, the archbishop said he still stands by his story: “I did receive such a call and fax from Panciroli,” Viganò said. “But that call and fax must have come on June 23, 1983 — the next day.”

In the November 1 interview with Valli, Viganò never actually makes the affirmation that the call and fax were on June 22. Valli begins by asking Viganò to “recall that evening” (the evening of Emanuela’s disappearance, June 22, 1983). Viganò starts to talk on the basis of that introductions, and in that context recalls receiving the phone call and fax. So he gives the impression that he is speaking about June 22, but he does not precisely say that.

The important “news” here is that Viganò is not backing off of his story, but indeed “doubling down,” insisting that, according to all ordinary procedures, the fax he says he received from Fr. Panciroli, and handed on to his superiors, must be still in the archives of the Secretariat of State.

A check of those archives can confirm or deny this story.

It does seem that, if true, as Viganò insists, any even faint hope of making a breakthrough in the Emanuela Orlandi case must begin with finding that fax.

(Note: The archbishop stressed to me this morning that he did not reach out to Valli to do the November 1 interview. Rather, the lawyer for Pietro Orlandi, Laura Sgrò, already a year and a half ago, impatient with the lack of response from Vatican officials to her requests for access to possible documents related to the Orlandi case, reached out to Viganò’s close associate and friend, Bishop Giorgio Corbellini, 72 (link), now quite ill. Corbellini approached Viganò, and Viganò, in the spring of 2018 (months before his August 2018 Testimony), met with Sgrò in her Rome office and told her what he has just told Valli, asking her to keep his identity secret. Sgrò asked the Vatican about the phone calls and the fax Viganò had mentioned to her, and received no answer. After a year and a half, Sgrò approached the journalist, Valli, to ask him to try to conduct a public interview with Viganò on these matters. Valli contacted Viganò, and Viganò agreed. This is the story behind the November 1 interview as I understand it.)

The Orlandi Case: Viganò Speaks: “Here are my recollections of that night in 1983”

On November 1, retired Italian Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò (78 and still living in hiding in an undisclosed location), gave a bombshell interview with Italian journalist Aldo Maria Valli. (Text below in my own translation from the original Italian.)

Viganò revealed, for the first time publicly, that he had received a remarkable phone call late in the evening in late June, 1983, while working in the Vatican Secretariat of State (where he worked from 1978 to 1989).

The call came at about 8 in the evening, and was from the then-director of the Vatican Press Office, Father Romeo Panciroli.

Panciroli told Viganò that an unidentified man, speaking Italian with a foreign accent, had just called the Vatican press office to say that Emanuela Orlandi, the 15-year-old daughter of an Italian layman employed at the Vatican bank (the IOR, the Institute for Religious Works) and so entitled, like several hundred other Italians who work inside the Vatican, to live with his family inside Vatican City, had been kidnapped.

Emanuela disappeared at about 6 p.m. on the evening of June 22.

The man on the phone, Panciroli said, had set forth specific conditions for obtaining Emanuela’s release.

Panciroli said those conditions would be sent over immediately to the Secretariat of State in a fax.

Such a fax was sent to Secretary of State a few minutes later, Viganò told Valli.

Viganò received the fax and read it.

It was not long — Viganò recalls it being about two paragraphs in length.

He also recalls being impressed by the clear style in which the conditions were set forth, but does not recall the precise details of the conditions proposed.

Viganò carried the fax down the hallway to his superior, the recently deceased Cardinal Achille Silvestrini, who read the text and then commented to Viganò that it seemed to be just a “bad joke.”

In other words, Silvestrini seemed not to take the text very seriously.

(Viganò did not know for sure, he told me this morning, whether the fax Panciroli sent was a fax received from the mysterious caller, or a text compiled in the Press Office from the words of the caller and so prepared by the Press Office as a fax.)

Valli’s long interview with Viganò created a firestorm in the Italian press.

Dozens of articles were written about the mysterious fax.

The man who made the call to Panciroli did call again, several times, always asking to speak only and exclusively with Cardinal Agostino Casaroli, the Vatican Secretary of State of that time, Viganò told me today.

But Viganò said that some of the calls came through first to him, and he heard the man’s voice, before transferring on the call.

The man had come to be nicknamed “the American,” but Viganò said his accent did not seem to him to be that of an American, but rather — and this was just his guess, he said — of someone from Malta.

A Maltese accent…

At the crossroads of the Cold War

The Orlandi family’s Italian lawyer, the tough, tireless Laura Sgrò, has never ceased to turn over whatever stone she stumbles across in seeking to shed light on what happened to Emanuela. She wants, and the family wants, to know the truth.

It seems — seems, because nothing in this case is clear — that Emanuela was kidnapped in connection with the assassination attempt on Pope John Paul II on May 13, 1981. (Some have suggested she was abducted into some sort of trafficking ring, or slavery, and even that she ran away of her own accord — there is no evidence for that theory — but several hints do suggest her disappearance was connected with the assassination attempt, so I say “it seems” connected.)

If this is so (and I think it possible, especially after this new testimony by Archbishop Viganò), then her case takes on a special poignancy.

For, if this is so, Emanuela became a pawn in an effort to free the Turkish gunman arrested in connection with that attempt, Ali Agca.

In other words, Emanuela may have been kidnapped in order to “trade” her freedom for Agca’s freedom. (I stress, this is only an hypothesis; we do not yet have sufficient evidence for this theory.)

This would mean that Emanuela’s case is linked directly (and tragically) to the “high politics” of the Cold War — of John Paul’s pontificate, of the Soviet regime’s fear of John Paul, of the rise of Solidarnosc in Poland, and later, of the efforts of US President Ronald Reagan to have the Berlin Wall, and “Iron Curtain,” torn down — all of which preceded the creation of the European Union and the united Europe ruled from Brussels which we have today.

So Emanuela may have gotten caught up in a battle she knew nothing about, a battle that should have had nothing to do with her.

Archbishop Viganò told me this morning that he thinks the probability is that, in order to ensure that she would never speak and so help to reveal her captors’ identities, she was at some point killed by her kidnappers.

This is motivation enough, perhaps, to continue, even 36 years later, to pursue the truth about what happened to Emanuela: to find out who kidnapped her, and, if she was indeed killed, who killed her.

The Complete Text of the Valli-Viganò Interview

Here is the complete text of the November 1 Viganò interview with Aldo Maria Valli.

Orlandi Case / Viganò speaks: “Here are my memories of that evening in 1983”

By Aldo Maria Valli (link)

In the festivities dedicated to the memory of the dead [Note: He is writing on November 1, All Saints’ Day] many of us will go to the cemeteries, for a visit to our loved ones, to place a flower on their grave. But in these days our thoughts also goes to the many people who, despite having lost a loved one, do not even have the consolation of being able to remember them in front of a tomb.

They are the relatives of those who have disappeared without a trace.

Like Emanuela Orlandi, the 15-year-old Vatican citizen who on June 22, 1983, in Rome, vanished into thin air.

More than 36 years have passed.

Since that day so many hypotheses, so many tracks, so many evaluations, certainly also many misleadings, but no truth. A wound still open and bleeding, and not only for the family, but for all those who care about justice.

Periodically the story of Emanuela returns to the fore, and so it was also last summer, when, following an application presented by the lawyer Laura Sgrò, lawyer of the Orlandi family, in the Teutonic cemetery, in the Vatican, two graves were opened.

“The tombs are empty,” the newspapers titled, after which silence fell again. In reality, bone fragments have been found, and lawyer Sgrò believes that we still need to investigate.

“After an initial examination on the found bones,” the lawyer of the Orlandi family tells us, “contrary to what is claimed by Professor Giovanni Arcudi, an expert witness, we believe that some remains deserve further study. We have made our requests and we have been waiting, for months now, to know the intentions of the Vatican judiciary in this regard. It is a shame to see that so much time is wasted. This story began on June 22, 1983, the path to truth should be everyone’s shared interest. What is certain is that, regardless of what will be decided, we will continue to follow every path that may lead us to Emanuela.”

But what, really, can finally lead to Emanuela?

The tracks covered are almost without number, but perhaps due attention has not yet been paid analytically to the very first moments after her disappearance.

We are talking about the evening of that June 22, 1983 and we refer, in particular, to what happened in the Vatican, in the offices of the Secretariat of State, the “nerve center” of the Holy See.

The very evening of the disappearance of Emanuela Orlandi, on June 22, 1983, around 8 pm (not even two hours after the girl was seen leaving the music school in Sant’Apollinare, near Piazza Navona), a stranger called the Vatican and he asked to speak urgently with the Secretary of State, Cardinal Agostino Casaroli. But Casaroli was traveling, in Poland, with Pope John Paul II, for an official visit, and was therefore unable to respond.

In the Secretariat of State at the time a monsignor of the curia worked whose name would become famous many years later. This is Carlo Maria Viganò.

The future Vatican nuncio in the United States, who last year, with his report on Cardinal (Theodore) McCarrick and the request for resignation addressed to Pope Francis, caused such an uproar, in 1983 was working closely with Archbishop Eduardo Martinez Somalo, who held the office of substitute for general affairs, a sort of interior minister.

Archbishop Viganò agreed to return with his memory to that evening of June 22, 1983, and here are his answers.

Monsignor, what was your job at the time? Where were you? Who did you work with?

Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò: Obviously after more than 30 years from that evening I cannot be precise about everything. In those years, from 1978 to 1989, I was in charge, together with Monsignor Leonardo Sandri, of the deputy secretary, who was then Archbishop Eduardo Martinez Somalo. That evening I was in the office of the Secretariat of State at the Terza Loggia (third floor) together with Monsignor Sandri, while the substitute was absent.

How did the news get to you?

Viganò: It was about 8 pm, or perhaps later, when I received a phone call from Father Romeo Panciroli, then director of the Vatican press office, who announced to me that an anonymous phone call had reached the press office announcing that Emanuela Orlandi had been kidnapped. Father Panciroli told me that he would immediately fax me a text with the contents of the call.

What was the content of the call, in detail? You later said that it consisted of two paragraphs. What did they say?

Viganò: Unfortunately, my memory does not assist me on the precise content of that document. It affirmed that Emanuela Orlandi was held by them and that her release was linked to a request, the fulfillment of which did not necessarily depend on the will of the Holy See. It was a message formulated in precise and well-constructed terms. It is undoubtedly available in the archive of the Secretariat of State.

Who else heard about the content of the call? After receiving the fax, what did you do? Who did you talk to?

Viganò: Since, as I said, the deputy was not in the office, I immediately went to the Second Section, what is now called the Section for Relations with States. Archbishop Achille Silvestrini (future cardinal, who died last August 29, ed) read the text and commented that according to him it was a joke in bad taste from some unbalanced person.

For my part, I pointed out that the text was drafted in very strict terms and written in a professional manner and therefore had to be taken into serious consideration.

Also, it occurred to me that the content of the anonymous phone call presented a strange coincidence with another story. Shortly before, a letter had arrived at the State Secretariat, signed by a self-styled refugee from an Eastern European country, who said he was in a refugee camp in Friuli [in northern Italy] and asked for political asylum in the Vatican. To the letter he attached a passport-size photograph of himself and a certificate of his registration to the same institute of sacred music attended by Emanuela Orlandi.

It was after 10 o’clock in the evening and with Monsignor Sandri we immediately called the person responsible for the archive to give us that document, which we handed over that evening to Dr. Volpe, of the public security inspectorate at the Vatican, so that he could make the appropriate investigations.

Who else was informed?

Viganò: In my role as a secretary, it was not given to me to know what initiatives Monsignor Silvestrini immediately took, but I have no doubt that he informed the deputy and the Cardinal Secretary of State Agostino Casaroli and also Pope John Paul II.

What were their reactions?

Viganò: Of great concern and great commitment to do everything possible to save Emanuela. Her parents, dismayed, came to the Secretariat of State to my superiors, and several times I saw them recite the rosary at the grotto of Lourdes, in the evening, in the Vatican gardens. A lawyer also came to the Secretariat to get information.

Later, a telephone line was reserved for communications with the alleged kidnappers, with the number 158. Did you also answer that phone?

Viganò: Yes, I also received some phone calls from what the media called “the American.”

The phone calls were in Italian, but from the pronunciation of that man I understood that it was not an American; rather than someone who had his own Maltese inflections. The interlocutor restricted himself to asking to speak only with Cardinal Casaroli and that was the reason why at a certain point a reserved line was created.

For our part, everything possible was done to ensure that this interlocutor could speak with Casaroli. Telephone appointments were made several times. But the cardinal waited in vain, because that individual never respected the established time and, perhaps to avoid the identification of the place where the phone call came from, he called back maybe an hour or two hours later.

The substitute also had contacts with the Italian magistrate responsible for counter-terrorism. To make sure that that high official (whose name unfortunately I don’t remember) was not seen entering the Vatican, a meeting took place at the apostolic nunciature to Italy in Via Po. I accompanied the substitute to that meeting. A telephone appointment had been fixed in the Secretariat for 10 o’clock at night on a specific day. When that day came, in the presence of the magistrate, we waited for the phone call until after 11 pm in my office, together with the substitute. Of course everything had been arranged by the Italian secret services to intercept the origin of the call, but it was useless. The phone call came after the magistrate left the Vatican, so much so that he, the magistrate, said he was convinced that he was dealing with the secret services of another state that knew his moves and confided to us that as a precaution he would immediately change the members of the his escort.

From the pages of the Pontifical Yearbook of 1983 it appears that in the Secretariat of State of the time there were many people who would later assume important positions: among them, just to name a few, the future cardinals Sepe, Sandri, Harvey, Re and Dziwisz , the last the special private secretary of John Paul II. It seems conceivable that at the time, and even later, these people became aware of details useful for the investigations. Have they been heard? Have they ever talked to you?

Viganò: In addition to the Secretary of State and the deputy, also the councilor Giovanni Battista Re and of course also Monsignor Dziwisz were among the people then on duty in the Secretariat of State who certainly came to know in detail what happened and the decisions taken in this regard. While in the second section, in addition to Monsignor Silvestrini, the undersecretary (who I believe was Monsignor Tauran) became aware of it and possibly also the minutante for Italy, whom I believe was Monsignor Mennini. Certainly the Annuario Pontificio contains a long list of names, but each one with competence in an individual section, while the case of Emanuela was treated with great discretion directly by the superiors. Even we secretaries of the substitute were told only the essentials in operational matters. In the secretariat of Cardinal Casaroli I think there was Monsignor Celata and perhaps even Monsignor Ventura. But I never had the opportunity to talk to them about it.

Were internal investigations started regarding the affair of Emanuela? If so, to whom were they entrusted?

Viganò: I never heard of any. If I had, my memory might have assisted me. But only the superiors of that time would be able to say.

Were there meetings between all of you in the Secretariat of State? Were you present? Did you at least hear about such meetings? Did he see you participate?

Viganò: I do not know if there were such meetings.

In those days were there visits from representatives of Italy?

Viganò: It is probable, but I have no memory of it. I believe it likely that the deputy spoke to the then-Italian ambassador to the Holy See, Claudio Chelli.

You say that in the first phone call it was stated that Emanuela was “held by them.” Can you tell us more about “them”? Who were they? Who did they say they were?

Viganò: I realize the vagueness of my answer, but my memory does not allow me to specify further.

According to you, the text of that phone call is kept in the archive of the Secretariat of State. Now wouldn’t it be a sign of transparency to make it known? Why does it remain secret?

Viganò: Of course, the text of that phone call, the note I received from Father Panciroli, must be in the archive of the Secretariat of State and I don’t know if it was ever given to Italian investigators. I would be surprised if it had not been.

You say that the text of that first phone call was written “in very strict terms” and was “professionally written.” Can you explain better what you mean? And what did you deduce from these formal features?

Viganò: The impression remained in my memory, that I had from the first reading, of the precision of the terms used in that text and therefore of the seriousness of what was asserted. I remember it well because my impression was completely different from that of Monsignor Silvestrini, who spoke of a “joke.”

Did you, after speaking with Monsignor Silvestrini, also turn to others?

Viganò: I spoke of it obviously at the first opportunity with monsignor substitute and with Monsignor Sandri, who could have a better memory than mine.

Do you think there is a copy of the letter from the Eastern European refugee asking for political asylum in the Vatican?

Viganò: This document should also be in the archives of the Secretariat of State.

You say that at first Silvestrini thought of a bad joke. But you also say: “I have no doubt that Silvestrini informed the deputy and the cardinal secretary of state Agostino Casaroli and also Pope John Paul II”. So Silvestrini immediately changed his mind? And how do you know that Silvestrini immediately went to the top? Did he tell you? Do you think that Silvestrini knew something more than he wanted to show?

Viganò: Silvestrini certainly did not have to tell me what he intended to do, but it is obvious that he could not not have spoken about it as soon as possible with the substitute and the cardinal. I don’t think that Silvestrini had any reason to mislead me by minimizing the fact.

You say the immediate reactions were “of great concern.” How was this concern expressed. Who expressed concern and why?

Viganò: From what was visible to an outside observer, even if in the substitute’s secretariat, I think the concern was obvious. But the tenor of the interviews between the superiors themselves was not communicated to others.

You also say that the situation was immediately addressed “with great commitment.” Can you explain better how this commitment manifested itself? Specifically, what did the Secretariat of State do?

Viganò: Unfortunately, I remain at the level of the impressions I had at the time and I am unable to define them better.

You say you personally received some of the phone calls from the so-called “American,” but in your opinion he would perhaps be a Maltese. What did he say to you? What do you remember about those phone conversations?

Viganò: The caller’s only request was to speak with Cardinal Casaroli. He did it insistently and said no more. The phone calls were only on this topic.

Do you think that Cardinal Casaroli conducted a private negotiation, beyond what was known?

Viganò: I have no idea. But on this point Monsignor Pier Luigi Celata, who was his trusted secretary, might know something.

—Aldo Maria Valli

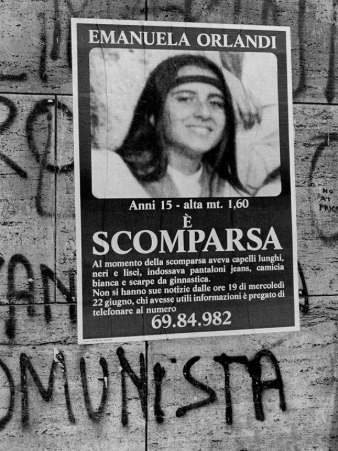

(Below, photos of Emanuela Orlandi, at her first communion, on a poster asking for help in finding her, and playing the flute, her instrument

Above, photographs of a young woman who disappeared in 1983, 36 years ago, when she was 15 years old. Her name: Emanuela Orlandi. She would be 51 if she were still alive.

Facebook Comments