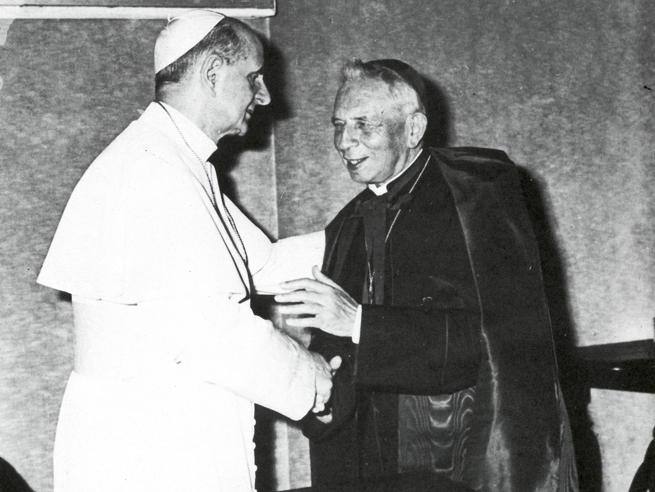

(Photograph by Dmitri Kessel, 1954)

Pope Paul VI with Cardinal Giacomo Lercaro (1891-1976). Lercaro served as Archbishop of Ravenna from 1947 to 1952 and of Bologna from 1952 to 1968. Pope Pius XII made him a cardinal in 1953.

Lercaro’s reputation as an outspoken critic of communism is believed to have been a contributing factor in Pius’s decision to make him the 1st Archbishop of Ravenna (31 January 1947) and then the 20th Archbishop of Bologna (19 April 1952), both among the largest Italian cities under communist rule.

During his tenure in Bologna, where the most popular political party was the Italian Communist Party, he tried to build a dialogue with the members of this party. Lercaro was also the first to popularize the theory of a “Church of the poor” that developed further in Latin America during the 1970s.

On June 20, 1966, Lercaro, the head of the Vatican Commission to prepare the text of the new Mass after the close of the Council in December, 1965, presented the first draft of the new liturgical rite to Pope Paul VI.

Early in 1968, Pope Paul VI accepted Lercaro’s resignation from the Bologna archdiocese and from his curial office as head of the liturgical commission. A book appearing later that year by a priest and historian, the Rev. Lorenzo Bedeschi, alleged that Paul, in ill health, had been persuaded by conservative members of the Curia to drop Lercaro after a sermon in which he condemned the American air war over North Vietnam as “un-Christian” and “evil.” The Vatican strongly denied the charge, which was made in the best-seller The Deposed Cardinal

“The Vatican has never given any reason for the dismissal of Archbishop Bugnini, despite the sensation it caused, and it has never denied the allegations of Masonic affiliation. (…) I very much regret that the question of Mgr Bugnini’s possible Masonic affiliation was ever raised as it tends to distract attention from the liturgical revolution which he masterminded. The important question is not whether Mgr Bugnini was a Mason but whether the manner in which Mass is celebrated in most parishes today truly raises the minds and hearts of the faithful up to almighty God more effectively than did the pre-conciliar celebrations...” —The late Michael Davies (1936-2004), in an article entitled “How the liturgy fell apart: the enigma of Archbishop Bugnini,” published in AD 2000 in June 1989. [Note: I met with Davies on several occasions in the 1990s and early 2000s, before his death in 2004.] The important point in this excerpt is that Davies in the end “very much regret[ted]” that the question of Msg Bugnini’s possible Masonic affiliation was ever raised. In other words, for Davies, the question distracted attention from the real issue… and I agree with him…

Letter #61, 2023 Tuesday, February 28: Yves Chiron on how the new Mass was made

For your possible reading at the beginning of Lent, here are two essays.

They are long.

They are somewhat repetitive.

And, they do not address the real “main question,” raised in the quotation above from the late Michael Davies, whom I knew: “Whether the manner in which Mass is celebrated in most parishes today truly raises the minds and hearts of the faithful up to almighty God more effectively than did the pre-conciliar celebrations.”

So this central question will have to be the subject of future letters.

Still, in the light of the present effort to officially “undo” the “compromise liturgical solution” promulgated by Pope Benedict XVI on July 7, 2007 in Summorum Pontificum — when Benedict defended the beauty and dignity and spiritual efficacy of the old liturgy, while also supporting the celebration of the new liturgy — it seemed fitting to put some facts and some theories “on the table,” as it were.

Experts in this question are quite familiar with everything contained in these two essays.

But the vast majority of ordinary Catholics have never heard of many, or most, of these things.

So, yes, my apologies, the articles are long, perhaps too long — but they are intended to provide those who are interested with some of the background of what happened in the matter of the liturgy, and is now happening, material for reflection.

The first essay (#1) was originally a chapter in a quite well-researched and fair 2020 biography of Monsignor Annibale Bugnini by French Catholic scholar Yves Chiron entitled Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy, Angelico Press, 2020, link). The essay was then published separately as an essay on July 22, 2021, entitled “How the Novus Ordo Mass was made.” (link)

The important thing one discovers in this essay is that the entire process of revising the Mass was “inorganic,” in the sense that it occurred in offices in Rome and even “over a terrace table” — quite literally, in one instance, over a restaurant terrace table in Trastevere, when a text needed to be submitted the next morning, and the authors stayed up late to complete it.

Chiron cites Fr. Louis Bouyer, who was drafting the Second Eucharistic Prayer in the new liturgy, as saying: “I cannot reread that improbable composition without recalling the Trastevere café terrace where we had to put the finishing touches to our assignment in order to show up with it at the Bronze Gate by the time our masters had set!”

So if there is one point I would propose for memory it is this: that the old rite grew up over centuries, and was the result of centuries; the new rite grew up over months, and parts of it were composed on a café terrace in Trastevere.

And because Pope Benedict knew this, he broke his pontificate on defending the old liturgy.

The second essay (#2) is by the late Michael Davies, a British convert to Catholicism, who made the study of the transition from the old to the new liturgy a central investigative question of his life. —RM

***

P.S. We have been selling subscriptions to Inside the Vatican magazine for several months at a reduced price of $20 per year in honor of our 30th year of publication. We will continue this rate for just one more month, then return to the regular price of $49.95 per year. We would love to gain new subscribers, of course, and at $20, perhaps some may feel, “why not?” and take out a subscription. After March 31, the offer will no longer be available… Click here to take out subscriptions at this reduced rate for friends, family members and anyone you think might like to receive the magazine.

P.P.S. Here is a link to our Special Edition on Mary, which many are saying is “the best issue of your magazine you ever made.” This beautiful issue about Mary, on special high-quality paper, is suitable for display on a coffee table, and may come to be regarded as a collector’s item (link)

P.P.P.S. If you would like to support this work, here is a link to our donation page. Thank you in advance.

(#1) How the Novus Ordo Mass Was Made (link)

by Yves Chiron

July 22, 2021

The incremental Vatican II reforms brought about by the September 1964 and May 1967 Instructions opened the way to a general reform of the Mass.

They lay the groundwork for it in two transitional phases, as it were.

A completely new rite of the Mass was slated for preparation from the very beginning of the Consilium [Council for the Implementation of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy].

During the fifth plenary session in April 1965 (20 members and 41 experts were in attendance), the possibility of modifying the Canon of the Mass was brought up.

As Archbishop (Annibale) Bugnini (link, 1912-1982) himself was later to admit, however, a very broad majority of members and consultors was of the opinion that this “venerable document” was not to be touched.

The first complete draft of a new Ordo Missae was ready for the sixth plenary session (October 18–26, 1965).

Msgr. Wagner, the relator for the tenth group, presented it.

It was the occasion for two “experimentations” that took place in the chapel of the “Maria Bambina” Institute: the first in Italian on October 20, the second in French on October 22 [in 1965].

The two celebrations of this “normative” Mass, as it was called, took place behind closed doors in the presence of Consilium members, who were then able to share their impressions in one of the Institute’s meeting rooms.

Paul VI had some concerns regarding this reform of the Ordo Missae.

On three different occasions (October 25, 1965, December 10, 1965, and March 7, 1966), he had his Secretary of State, Cardinal (Amleto Giovanni) Cicognani (1883-1973) address official letters to Cardinal(Giacomo) Lercaro (link, 1891-1976) to recommend prudence and reserving to the Holy See any decision involving “any possible changes proposed for the rite of celebration of the divine sacrifice.”

On June 20, 1966, the revised first draft of the new Mass was presented to Paul VI by Cardinal Lercaro.

The pope wanted two important changes:

- the present anaphora [the Roman Canon] is to be left untouched; two or three other anaphoras should be composed, or sought in existing texts, that could be used during certain defined seasons.

- the Kyrie should be retained when the Gloria is not said; when the liturgy prescribes the Gloria, however, the Kyrie should be replaced with another penitential prayer.

Consequently, a Consilium subcommission prepared three new anaphoras (or Eucharistic Prayers). Two were new compositions while the third (which became the second Eucharistic Prayer in the new Ordo Missae) was inspired by the anaphora of Saint Hippolytus.

Archbishop Bugnini was later to acknowledge that one of these new Eucharistic Prayers (which became the fourth Eucharistic Prayer) was put together in haste, “a kind of forced labor.”

A consultor on that subcommission, Fr (Louis) Bouyer, gave the same description (not without humor and irony) for the composition of the second Eucharistic Prayer that he prepared with Dom Botte, the famous Hippolytus specialist.

He had to compose it posthaste, within a twenty-four-hour period:

Between the indiscriminately archeologizing fanatics who wanted to banish the Sanctus and the intercessions from the Eucharistic Prayer by taking Hippolytus’s Eucharist as is, and those others who could not have cared less about his alleged Apostolic Tradition and wanted a slapdash Mass, Dom Botte and I were commissioned to patch up its text with a view to inserting these elements, which are certainly quite ancient—by the next morning! Luckily, I discovered, if not in a text by Hippolytus himself certainly in one in his style, a felicitous formula on the Holy Ghost that could provide a transition of the Vere Sanctus type to the short epiclesis. For his part Botte produced an intercession worthier of Paul Reboux’s “In the manner of…” than of his actual scholarship. Still, I cannot reread that improbable composition without recalling the Trastevere café terrace where we had to put the finishing touches to our assignment in order to show up with it at the Bronze Gate by the time our masters had set!

Nine new Prefaces were composed at this time, of which eight were retained.

Fr Bouyer sees them in a more positive light: “The only element undeserving of criticism in this new missal was the enrichment it received, thanks particularly to the restoration of a good number of splendid prefaces taken over from ancient sacramentaries.”

An Experimental Mass at the Synod of 1967

The new Mass in its completed structure was presented to some 180 cardinals and bishops in a Synod at the Vatican in 1967. This first postconciliar Synod was to deal with several topics: the revision of the code of canon law, doctrinal questions, and the liturgical reform. On October 21, Cardinal Lercaro presented the assembled cardinals and bishops with a report describing the new structure of the Mass and the changes introduced into it, as well as the reform of the Divine Office. On October 24, Fr Bugnini celebrated a “normative” Mass before the Synod Fathers in the Sistine chapel. Paul VI did not attend this celebration because of an “indisposition,” however.

Besides the changes that were already in force since the 1964 and 1967 Instructions (Mass celebrated facing the people in Italian including the Canon, fewer genuflections and signs of the cross, etc.), the “normative” Mass that Fr Bugnini celebrated with a large choir added other new elements: a longer Liturgy of the Word (three readings total), a transformed Offertory, a new Eucharistic Prayer (the third), and a great number of hymns.

During the four general congregations devoted to the liturgy (October 21–25), cardinals and bishops made many comments on this “normative” Mass and on the liturgical reform in general.

All told, sixty-three cardinals, bishops, and religious superiors general commented on the subject and a further nineteen submitted written comments. There was a diversity of opinion. “Of sixty-three orators,” Fr Caprile reported, “thirty-six explicitly expressed, in the warmest, most enthusiastic, and unreserved terms,” their agreement with the reform underway and its results. Some bishops even wanted further changes, such as the possibility of receiving communion in the hand, that of using ordinary bread for communion, and the preparation of a specific Mass for youth, etc.

Yet the general tone was more prudent, if not reserved or even critical. The English-speaking bishops met at the English College to define a common position on the “normative” Mass. On October 25, at the Synod, Cardinal Heenan, Archbishop of Westminster, took the floor to accuse the Consilium of technicism and intellectualism and to blame it for lacking pastoral sense. More significant yet, in the sense that they came from the highest authority in the Church after the pope, were the words of Cardinal Cicognani, Secretary of State, who on the very same day asked for an end to liturgical changes “lest the faithful be confused.”

Twice during the debates on the liturgy, the participants were invited to express their opinion through a vote. On October 25, they answered four questions that Paul VI had specifically posed: on the three new Eucharistic Prayers, on two changes in the formula of consecration, and on the possibility of replacing the Niceno-Constantinopolitan creed with the Apostles’ Creed. Eight more questions were posed on October 27, particularly on the normative Mass and on the Divine Office draft.

Leaving aside a detailed analysis of these twelve votes, it is noteworthy that for half of them (two out of the pope’s four questions and four out of eight of the remainder), the required two-thirds majority was not reached. There were 187 voters; the two-thirds majority was therefore 124. For some of the votes, the tally was far from it, with the non placet (nays) and placet juxta modum (approval on condition of modifications) having a broad margin. For example, regarding the suppression of the phrase Mysterium fidei in the consecration formula, there were only 93 placet. More spectacular yet was the refusal to give unreserved approval to the general structure of the normative Mass: 71 placet; 43 non placet; 62 placet juxta modum; 4 abstentions.

A few months later Fr Bugnini acknowledged to Consilium consultors and members that “the response of the bishops was not unanimous. The votes in the Synod went to some extent contrary to what the Consilium wanted [contro il ‘Consilium’].”

Lercaro’s “Destitution”

This public disavowal of the Consilium’s work was one of the causes that led to Cardinal Lercaro’s destitution.

In August 1966, Cardinal Lercaro, who was reaching the age limit of 75 imposed on bishops and curial officials, had presented his resignation to the pope.

Paul VI had asked him to continue in his functions as both archbishop of Bologna and president of the Consilium.

Nevertheless, Paul VI named one of his close collaborators, Msgr. Poma, as coadjutor in the archdiocese of Bologna in June 1967.

Then, unexpectedly for the cardinal, Paul VI wrote to Lercaro on January 9, 1968 to tell him that he accepted his resignation from the Consilium.

The pope sent him a representative on the following 27th, whose mission was to secure the cardinal archbishop’s resignation [from the See of Bologna], which the latter, with a heavy heart, submitted on February 12.

One of Lercaro’s close collaborators, Don Lorenzo Bedeschi, presented this double resignation as a “destitution.”

History, in the main, has accepted this view.

Diverse reasons led to this double destitution: Cardinal Lercaro’s controversial pastoral policies in Bologna, his links to the Communist municipality (he agreed to being made an “honorary citizen”), his appeal against American bombing in Vietnam.

Yet his management of the liturgical reform was also questioned.

In 1967 the backlash linked to Casini’s pamphlet and the criticism leveled at the “normative” Mass had brought to light the opposition to the work of the Consilium, whose president he had been since 1964.

One may therefore say that Paul VI attempted to regain control of the liturgical reform in early 1968.

Just as he officially accepted the resignation of the Consilium president, he simultaneously asked Cardinal Larraona to resign from the Congregation of Rites.

On the same day Cardinal Gut, a Benedictine monk who was already a Consilium member, became its president as well the new prefect of the Congregation of Rites.

This double nomination anticipated the fusion of the two organisms, which would occur the following year.

Paul VI still had full confidence in Bugnini, however.

During the audience that followed Lercaro’s resignation, Paul VI told Bugnini: “Now you alone are left. I urge you to be very patient and very prudent. I assure you once again of my complete confidence.”

Fr Bugnini answered: “Holy Father, the reform will continue as long as Your Holiness retains this confidence. As soon as it lessens, the reform will come to a halt.”

Towards the “New Mass”

The Consilium put the “new Mass” project, which had been roundly criticized at the October 1967 Synod, back on the drawing board. We have seen that Paul VI had been unable to attend the first experiment of the “normative” Mass.

A report prepared under Fr Bugnini’s direction had been presented to him on December 11, 1967.

During an audience on January 4, 1968, he asked Fr Bugnini to organize three new “experimental” celebrations, to take place in his presence in the Matilda chapel on the second floor of the Apostolic Palace.

These three “normative” Masses were all celebrated in the late afternoon by one of Bugnini’s two closest collaborators, each with a different Eucharistic prayer, but in different modes of celebration: on January 11, a read Mass with hymns celebrated by Fr Carlo Braga; on January 12, an “entirely read Mass with participation of the faithful” celebrated by Fr Gottardo Pasqualetti; and on January 13, a sung Mass, once again celebrated by Fr Braga.

Each of the celebrations was attended by about thirty people besides the pope: the cardinal Secretary of State, different members of the Curia, several members of the Consilium, two religious women, and four laymen (two men and two women).

These three experimental celebrations in the presence of the pope presented a few differences with the “normative” Mass that had been celebrated before the Synod a few months earlier, in particular by the introduction of a “Sign of Peace” that all in attendance exchanged after the instruction “Give each other the Peace.”

After each of the Masses, the pope welcomed some of the participants along with Fr Bugnini in his private library to share impressions and comments on what had been done in the celebration.

On the following January 22, Paul VI provided his own written comments during an audience he granted to Fr Bugnini.

The pope made seven suggestions, asking in particular that the Offertory should be given more prominence since it “should be the part of the Mass in which . . . [the faithful’s] activity is more direct and obvious.”

He also asked that the expression Mysterium fidei should be maintained at the end of the formula of consecration, “as a concluding acclamation of the celebrant, to be repeated by the faithful” and that the triple Agnus Dei invocation should be retained.

Paul VI once again echoed some “authoritative persons” who asked that the last Gospel at the end of Mass (the prologue of the Gospel according to St. John) should be restored. Lastly, he asked that “the words of consecration . . . not be recited simply as a narrative but with the special, conscious emphasis given them by a celebrant who knows he is speaking and acting ‘in the person of Christ’.”

Also on January 22, Paul VI asked that the schema of the new Mass be sent, after revision, to all the Curia dicastery heads, a number of whom had expressed reservations or criticisms of the Synod “normative” Mass.

“We must win them over and make allies of them,” the pope explicitly said, even if this entailed the argument from authority: “You saw, didn’t you, what happened when St. Joseph’s name was introduced into the Canon? First, everyone was against it. Then one fine morning Pope John decided to insert it and made this known; then everyone applauded, even those who had said they were opposed to it.”

The following May 23, Cardinal Gut, prefect of the Congregation of Rites and president of the Consilium, published a decree authorizing the use of the three new Eucharistic Prayers and of eight new Prefaces. They could be used starting on August 15, 1968.

Once again, the traditional rite of the Mass was emended on important points before the new rite was completed and promulgated.

On June 2, 1968, the revised draft of the new Ordo Missae was sent, as Paul VI had intended, to fourteen curial cardinals (Congregation prefects and Secretariat presidents). Fr. Bugnini was to report that “of the fourteen cardinals involved, two did not reply, seven sent observations, and five said simply that they had no remarks to make or were ‘very pleased’ with the schema.”

It is noteworthy that the Institutio Generalis Missalis Romani (the “General Instruction of the Roman Missal”), which was to preface the new Ordo Missae, was not sent to these cardinals, not even to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

This Institutio, which was made up of eight chapters and put together by a study group directed by Fr Carlo Braga, presented itself as “at once [a] doctrinal, pastoral, and rubrical” treatment of the new Mass. Certain articles of this Institutio would come under criticism, as we shall see.

Paul VI had the revised draft and the cardinals’ responses examined by two of his close collaborators, Msgr. Carlo Colombo, his private theologian, and Bishop Manziana of Crema.

Then he read and reread the draft himself, inserting marginal notes and underscoring the text in red and blue pencil, though without seeking to impose his views.

On September 22, 1968, he gave the annotated draft back to Fr. Bugnini with the following written remark: “I ask you to take account of these observations, exercising a free and carefully weighed judgment.”

From October 8 to 17, the Consilium’s eleventh plenary session met to work on the Mass, but also on other rites (notably the Blessing of an Abbot and Religious Profession).

Paul VI hosted the participants on October 14 and gave a long allocution.

Its tone was graver than on any previous occasion.

The pope issued several warnings: “Reform of the liturgy must not be taken to be a repudiation of the sacred patrimony of past ages and a reckless welcoming of every conceivable novelty.”

He insisted on the “ecclesial and hierarchic character of the liturgy”:

The rites and prayer formularies must not be regarded as a private matter, left up to individuals, a parish, a diocese, or a nation, but as the property of the whole Church, because they express the living voice of its prayer. No one, then, is permitted to change these formularies, to introduce new ones, or to substitute others in their place.

More than this, Paul VI for the first time publicly deplored abuses committed by certain conferences of bishops:

This results at times even in conferences of bishops going too far on their own initiative in liturgical matters. Another result is arbitrary experimentation in the introduction of rites that are flagrantly in conflict with the norms established by the Church. Anyone can see that this way of acting not only scandalizes the conscience of the faithful but does harm to the orderly accomplishment of liturgical reform, which demands of all concerned prudence, vigilance, and above all discipline.

The Novus Ordo Missae (N.O.M.)

On November 6, 1968, Paul VI, after rereading the new Ordo Missae one more time, gave it his written “approbation.” The Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanum of April 3, 1969 was announced in Consistory on the following April 28 and presented to the press on May 2, the publication day of the new Ordo Missae, which was soon called the “new Mass” or the N.O.M. (Novus Ordo Missae).

A new missal, soon commonly termed the “Paul VI Missal,” was about to succeed the Roman Missal codified by Saint Pius V.

The rite of the Mass was now “simplified.” In fact, we have seen that between the traditional Missal used on the eve of the Council in 1962 and the 1969 Missal, there had been a succession of transformations: the N.O.M. was not a pure innovation. In some of its formulations, the Institutio Generalis was far more innovative.

It is worth noting that this lengthy “General Presentation” was not submitted to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith before publication. A number of infelicitous expressions provoked fierce criticism.

The “new Mass” was actually not as new as was claimed.

Indeed, considering prior Instructions, it synthesized and made official the changes that had already been taking place: a more communal penitential part of the Mass; more numerous and diverse Sunday readings spread out over a three-year cycle; a restored “universal prayer”; new Prefaces; a changed Offertory; three new Eucharistic Prayers added to the ancient Roman Canon to be used at the celebrant’s choice; modified words of consecration, identical in all four Eucharistic Prayers; the Pater noster said by the whole congregation, no longer by the priest alone; suppression of many genuflections, signs of the cross, and bows.

The Path to Communion in the Hand

As we have seen, in 1965 Cardinal Lercaro, president of the Consilium, considered “placing the host in the open hands of the faithful” to be a deplorable and fanciful initiative.

Neither the 1969 Missal nor the Institutio Generalis provided for the possibility of receiving communion in the hand. Yet the practice had already spread in several countries. The Congregation for Divine Worship therefore published a lengthy Instruction on the topic dated May 29, 1969.

As Jean Madiran was later to point out, this Instruction looks like a composite document.

On the one hand, the Instruction uses different arguments (theological, spiritual, and practical) to defend the traditional manner of receiving communion and states that it must remain the norm: “In view of the overall contemporary situation of the Church, this manner of distributing communion must be retained. Not only is it based on a practice handed down over many centuries, but above all it signifies the faithful’s reverence for the Eucharist.”

In support of maintaining this tradition, the same document published the results of a survey conducted among all Latin-rite bishops. Without getting into the detail of the answers given to the three questions, we give here only those given to the first question: “Do you think that a positive response should be given to the request to allow the rite of receiving communion in the hand?”

In favor: 567

Opposed: 1,253

In favor with reservations: 315

Invalid votes: 20

On the basis of the survey’s results, the Instruction prescribed the following: “[Pope Paul VI’s] judgment is not to change the long-accepted manner of administering communion to the faithful. The Apostolic See earnestly urges bishops, priests, and faithful, therefore, to obey conscientiously the prevailing law, now reconfirmed.”

Yet in the second part, which is shorter and looks like an add-on, the same text granted to episcopal conferences the possibility of authorizing communion in the hand:

Wherever the contrary practice, that is, of communion in the hand, has already come into use, the Apostolic See entrusts to the same conferences of bishops the duty and task of evaluating any possible special circumstances. This, however, is with the proviso both that they prevent any possible lack of reverence or false ideas about the Eucharist from being engendered in the attitudes of the people and that they carefully eliminate anything else unacceptable.

Cardinal (Silvio) Oddi reports that, from a concern not to restrict the freedom of episcopal conferences and to respect the diversity of opinions, Paul VI refused to impose a single law in the matter, although he was personally opposed to communion in the hand. In any event, what had been a limited concession in 1969 has become the norm in a great many countries and parishes.

Pierre Lemaire, director of the review Défense du Foyer and of the Éditions Saint-Michel and an activist in defense of the family and of the catechism, voiced a complaint on the subject in Rome.

In 1969, during one of his many visits to the Vatican, he was received by Cardinal Seper, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and by Cardinal Wright, new prefect of the Congregation for Clergy.

He gave each of them a Pro memoria exposing “the dramatic and catastrophic confusion in which France finds herself” and the “fundamental points” that were introducing a “rupture” between Catholics faithful to the Holy See and the clergy.

Pierre Lemaire underscored the “crisis” that the liturgical question had precipitated:

The aberrant liturgies invading our churches—now as bare as Protestant houses of worship—are having a disastrous effect. Communion in the hand, often distributed in baskets to all takers, represents the nadir of the innumerable profanations spreading in progressive parishes because of the multiplying sacrilegious communions of the “faithful” who never go to confession. In this climate, the new “Ordo Missae” is received not as a step forward but as the herald of further degradations, since the clergy, which is badly formed and badly taught in wayward seminaries, is open to any and all experiments.

The Congregation for Divine Worship

The promulgation of the new Missal did not mean that the implementation of the liturgical reform was at an end; it indicated that the reform was at its height.

Paul VI, in a consistory held on April 28, 1969, announced that the venerable Congregation of Rites was to be divided into two Congregations: the Congregation for Divine Worship focusing on the liturgy in particular and the Congregation for the Causes of Saints that was to handle beatification and canonization causes.

The Apostolic Constitution Sacra Rituum Congregatio of May 8, 1969 established two new Congregations. The Consilium no longer existed as an autonomous body: it was integrated into the new Congregation for Divine Worship under the title “Special Commission for the Implementation of the Liturgical Reform.”

Cardinal Gut was named prefect and Fr Bugnini secretary of this new Congregation. Although his title remained unchanged (“secretary”) and he was not yet given the prelature granting him the title “Monsignor,” Fr. Bugnini was completely integrated into the Curia. He left the old Palazzo Santa Marta buildings to set up with his collaborators on the fourth floor of the nice modern Palazzo dei Congregazioni, at 10 Piazza Pio XII.

He now belonged to a Curia dicastery, which strengthened his authority but at the same time reduced his autonomy. The new Congregation “was to be organized according to the structures and regulations of the other curial departments.” Only seven of the forty Consilium bishops stayed on as members of the new Congregation and the number of consultors was considerably reduced: only nineteen remained.

Cardinal Gut, prefect of this new Congregation, tried to channel the liturgical ferment that had been disrupting the lives of the faithful in many parishes. In an interview sometime after the creation of the Congregation for Divine Worship, he announced that “stricter measures” would be taken.

He said: “At present the limits of the conciliar Constitution on the Liturgy have been vastly overrun in many areas. Many elements have been introduced, with or without authorization, which go beyond the liturgy schema.”

He hoped that this “fever of experimentation [would] soon come to an end” and, surprisingly, he (respectfully) lay part of the blame at the feet of the pope: “These unauthorized initiatives often could no longer be stopped because they had spread too far abroad. In his great goodness and wisdom the Holy Father then gave in, often against his own will.”

The Ottaviani Intervention

The new Ordo Missae was to come into effect on November 30, 1969, the first Sunday of Advent.

Even before this date, however, the severest doctrinal critiques proliferated, some with the support of eminent authorities.

They aimed both at the Ordo Missae and at the Institutio Generalis prefacing it.

Even a review so attached to romanità as La Pensée catholique published, under collective authorships (“a group of theologians” and “a group of canonists”), two lengthy critiques of the new Ordo Missae.

The group of theologians lamented that the new Mass “completely disregards the doctrine of the Council of Trent on the Mass: incruens sacrificium” and deemed that it “is not in conformity with the tradition of the Roman Church.”

The most glaring opposition came from a Short Critical Study of the New Order of Mass.

This Short Critical Study, which is dated to the feast of Corpus Christi (June 5, 1969) but was only published a few months later, was unsigned at the time.

The letter that Cardinals Ottaviani and Bacci wrote to Paul VI to introduce the Study indicates that it was composed by “a select group of bishops, theologians, liturgists and pastors of souls.”

It later transpired that a laywoman, the Italian writer Cristina Campo(1923–1977), and the Dominican theologian Michel Guérard des Lauriers, professor at the Dominican-run Pontifical University Angelicum, had an essential role in writing this document.

The Short Critical Study began by questioning the definition of the Mass that the Institutio Generalis presented at chapter 3, §7: “The Lord’s supper or Mass is the sacred assembly or congregation of the people of God gathering together, with a priest presiding, in order to celebrate the memorial of the Lord.”

The term “supper” was taken up again at §§8, 48, 55, and 56. The Short Critical Study deplored this in the following terms:

None of this in the very least implies:

The Real Presence.

The reality of the Sacrifice.

The sacramental function of the priest who consecrates.

The intrinsic value of the Eucharistic Sacrifice independent of the presence of the “assembly.”

The Short Critical Study spoke in scholastic categories when it also regretted that the “ends or purposes” of the Mass (ultimate, ordinary, immanent) did not appear clearly.

It also questioned the formulas of consecration and the place of the priest in the new rite: a “minimized, changed, and falsified” role.

This relentless critique ended in a total rejection of the “new Mass” which “due to the countless liberties it implicitly authorizes, cannot but be a sign of division—a liturgy which teems with insinuations or manifest errors against the integrity of the Catholic Faith.”

Two cardinals, Bacci and Ottaviani, who no longer had any official functions in the Curia, agreed to present this Short Critical Study to the pope.

They did so in a letter accompanying the document. In this letter, dated September 25, 1969, the two cardinals judged that “the Novus Ordo Missae—considering the new elements susceptible to widely different interpretations which are implied or taken for granted—represents, both as a whole and in its details, a striking departure from the Catholic theology of the Mass.”

In consequence, they were asking for the new rite of the Mass to be “abrogated.”

Although other cardinals and bishops had been approached to sign this plea, none made up their mind to take that step.

Cardinal (Giuseppe) Siri, Archbishop of Genoa, thought that this Study was “more Bacci’s doing than Ottaviani’s” and that Cardinal Ottaviani gave his signature when the text had already been printed.

Cardinal Siri added that he himself “would not have added his signature if he’d been asked.”

Generally speaking, Cardinal Siri’s views on the liturgical reform were simple:

The Council did not ask for any such revolution. The liturgical reform was done, the pope approved it, and that’s enough: I take the position of obedience, which is always owed to the pope. If he had asked me, I think I might have made some observations—several. But once a law has been approved, there is only one thing left to do: obey.

The Short Critical Study came to Paul VI’s knowledge in September 1969; the press began to trumpet the story in the following month.

The pope sent the Study to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith for review.

Cardinal Seper, the Congregation prefect, gave his answer by November 12: “The pamphlet Breve esame . . . contains many superficial, exaggerated, inaccurate, biased, and false statements.”

Jean Madiran had been the first in France to publish the letter of Cardinals Bacci and Ottaviani.

He was also the first to publish the French version of the Short Critical Study of the New Order of Mass.

On the other hand, in 1970 Pierre Lemaire published as a supplement to Défense du Foyer 111 a small brochure under the sober title Note doctrinale sur le Nouvel Ordo Missae (“Doctrinal Note on the New Ordo Missae”).

This forty-four-page brochure was commissioned, as the text says, “by the Knights of Our Lady,” an organization to which Pierre Lemaire belonged.

In fact, the main writer of this “Note” was Dom Gérard md, the Order’s chaplain and a monk at the abbey of Saint Wandrille where he taught Sacred Scripture.

The Doctrinal Note, while it did express some criticisms regarding the translation of the new Ordo Missae then circulating in France, came to the defense of the new Mass’s orthodoxy.

The Doctrinal Note also expressed the opinion that “Cardinal Ottaviani cannot have given his approval to the Short Critical Study; they probably refrained from reading it to him.”

Dom Lafond’s study had been sent to different authorities for review before being published by Pierre Lemaire along with excerpts of the responses they had sent in.

Cardinal Journet had praised these “solid, luminous, balanced pages.” Fr Louis Bouyer, a renowned theologian and liturgical specialist, found the work “quite good.”

Msgr Agustoni, Cardinal Ottaviani’s secretary, praised what he called “a serious, deep, serene work accomplished in the eye of the storm.”

Then, the following month, Pierre Lemaire published a letter from Cardinal Ottaviani that caused a sensation.

This letter, which was addressed to Dom Lafond to thank him for the Note doctrinale, was in near complete counterpoint to the Short Critical Study published a few months before.

In this letter Cardinal Ottaviani characterized Dom Lafond’s Note doctrinale as “remarkable for its objectivity and its dignity of expression.”

He also deplored the publicity that had been given to his letter to Paul VI: “I regret that my name has been abused in a direction I did not want through the publication of a letter addressed to the Holy Father, without my having authorized anyone to publish it.”

Above all, Cardinal Ottaviani expressed his satisfaction with the allocutions Paul VI had given in general audience on November 19 and 26, 1969, and judged that henceforth “no one can be scandalized anymore,” even though “there is need for prudent and intelligent catechesis to remove a few legitimate perplexities that the text may arouse.”

Paul VI’s Corrections and Rectifications

To Jean Madiran, the letter from Cardinal Ottaviani to Dom Lafond seemed to be a provocation against the truth.

A lively polemic ensued. Jean Madiran published a brochure in response to the Note doctrinale, its author, and Pierre Lemaire who had published it. He also questioned the authenticity of the letter from Cardinal Ottaviani to Pierre Lafond.

This he did in highly polemical terms, judging that, in this whole business, Dom Lafond and Pierre Lemaire had been “duped and manipulated.”

In reality and according to diverse well-known attestations, one may consider that Cardinal Ottaviani had most certainly first approved the Short Critical Study, of which he was not the author.

Then, a few months later, he gave his approval to Dom Lafond’s Note doctrinale.

His position regarding the “new Mass” (which he went on to celebrate) had changed because in the meantime Paul VI had provided corrections and rectifications of no small import.

Indeed, at the time neither the enthusiastic partisans of the new Mass and of the liturgical reform nor its most determined adversaries paid sufficient attention to what the pope did and said to rectify and correct the texts he had first approved and promulgated.

On the one hand, there were the allocutions given during the general audiences on November 19 and 26, 1969, two Wednesdays in a row.

They were entirely devoted to the new Mass. Paul VI had explained the reasons for the changes in the rite and reaffirmed that it substantially “is and will remain the Mass it always has been”: a sacrifice offered by the priest “in a different mode, that is, unbloodily and sacramentally, as his perpetual memorial until his final coming.”

He acknowledged that abandoning Latin was a “great sacrifice,” necessary for a better “understanding of prayer.”

He also asserted: “Finally, close examination will reveal that the fundamental plan of the Mass in its theological and spiritual import remains what it always has been.”

The phrase “close examination” is worth noting: it acknowledged that continuity between the “old” Mass and the “new” was not obvious or immediately apparent.

There were also the important corrections to the Institutio Generalis.

Under the pressure of the moment, so to speak, Cardinal Gut and Fr Bugnini published a “Declaration” to specify that the Institutio “is not to be considered as a doctrinal or dogmatic document but as a pastoral and ritual instruction describing the celebration and each of its parts.”

Then there were the additions and corrections made to many articles of the Instructio itself.

These are easy to pick out in a synoptic comparison of the 1969 editio typica and the 1970 editio typica. In the first place a lengthy, fifteen-paragraph Proemium (“Preamble”) had been added; it repeated the traditional Catholic doctrine of the Mass as a propitiatory sacrifice and notably cited the definitions of the Council of Trent several times.

The chapters of the Instructio themselves had been corrected in several points by addition or by a different formulation.

The famous §7 which, in the 1969 edition, gave a more than incomplete definition of the Mass, was corrected to yield a more complete and more theologically accurate definition.

While it defined it again as a gathering and memorial—“At Mass or the Lord’s Supper, the people of God are called together, with a priest presiding and acting in the person of Christ, to celebrate the memorial of the Lord”—the new text defined it as a sacrifice also, and insisted on transubstantiation and the Real Presence: “For at the celebration of the Mass, which perpetuates the sacrifice of the Cross, Christ is really present to the assembly gathered in his name; he is present in the person of the minister, in his own word, and indeed substantially and permanently under the Eucharistic elements.”

The typical edition of the Missale Romanum published in Rome in 1970 also included substantial corrections, even though its structure remained unchanged.

In fact, within a few months, the text of the new Ordo Missae as well as that of the Institutio Generalis had undergone revisions that were not merely marginal changes.

These did not satisfy those who had for several months been multiplying criticisms on both form and substance.

On the other hand, some were convinced and changed their views; for instance, Fr Luc Lefèvre retracted his initial critical stance and, in an editorial in La Pensée catholique, affirmed: “All the ambiguities have definitively and officially been set aside, then. Bene. Recte. Optime.”

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is excerpted from Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy. Copyright ©Angelico Press, 2020. Reprinted by arrangement with Angelico Press.

And here is the 1989 article by Michael Davies cited at the outset of this letter:

(#2) How the liturgy fell apart: the enigma of Archbishop Bugnini (link)

By Michael Davies, AD 2000, June 1989

Archbishop Annibale Bugnini, who died in Rome on 3 July 1982, was described in an obituary in The Times as “one of the most unusual figures in the Vatican’s diplomatic service.” It would be more than euphemistic to describe the Archbishop’s career as simply “unusual”.

There can be no doubt at all that the entire ethos of Catholicism within the Roman Rite has been changed profoundly by the liturgical revolution which has followed the Second Vatican Council.

As Father Kenneth Baker SJ remarked in his editorial in the February 1979 issue of the Homiletic and Pastoral Review: “We have been overwhelmed with changes in the Church at all levels, but it is the liturgical revolution which touches all of us intimately and immediately.”

Commentators from every shade of theological opinion have argued that we have undergone a revolution rather than a reform since the Council. Professor Peter L. Berger, a Lutheran sociologist, insists that no other term will do, adding: “If a thoroughly malicious sociologist, bent on injuring the Catholic community as much as possible had been an adviser to the Church, he could hardly have done a better job.”

Professor Dietrich von Hildebrand expressed himself in even more forthright terms: “Truly, if one of the devils in C.S. Lewis‘ The Screwtape Letters had been entrusted with the ruin of the liturgy he could not have done it better.”

Major Conquest

Archbishop Bugnini was the most influential figure in the implementation of this liturgical revolution, which he described in 1974 as “a major conquest of the Catholic Church.”

The Archbishop was born in Civitella de Lego, Italy, in 1912. He was ordained into the Congregation for the Missions (Vincentians) in 1936, did parish work for ten years, in 1947 he became active in the field of specialised liturgical studies, was appointed Secretary to Pope Pius Xll’s Commission for Liturgical Reform in 1948, a Consultor to the Sacred Congregation of Rites in 1956; and in 1957 he was appointed Professor of Sacred Liturgy in the Lateran University.

In 1960 Father Bugnini was placed in a position which enabled him to exert a decisive influence on the future of the Catholic Liturgy: he was appointed Secretary to the Preparatory Commission for the Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council.

He was the moving spirit behind the drafting of the preparatory schema, the draft document which was to be placed before the Council Fathers for discussion.

It was referred to as the “Bugnini schema” by his admirers, and was accepted by a plenary session of the Liturgical Preparatory Commission in a vote taken on 13 January 1962.

The Liturgy Constitution for which the Council Fathers eventually voted was substantially identical to the draft schema which Father Bugnini had steered successfully through the Preparatory Commission in the face of considerable misgivings on the part of Cardinal Gaetano Cicognani, President of the Commission.

The First Exile

Within a few weeks of Father Bugnini’s triumph his supporters were stunned when he was summarily dismissed from his chair at the Lateran University and from the secretaryship of the Liturgical Preparatory Commission. In his posthumous La Riforma Liturgica, Archbishop Bugnini blames Cardinal Arcadio Larraona for this action, which, he claims, was unjust and based on unsubstantiated allegations. “The first exile of P. Bugnini,” he commented (p.41).

The dismissal of a figure as influential as Father Bugnini could not have taken place without the approval of Pope John XXIII, and, although the reasons have never been disclosed, they must have been of a very serious nature. Father Bugnini was the only secretary of a preparatory commission who was not confirmed as secretary of the conciliar commission. Cardinals Lercaro and Bea intervened with the Pope on his behalf, without success.

The Liturgy Constitution, based loosely on the Bugnini schema, contained much generalised and, in places ambiguous terminology. Those who had the power to interpret it were certain to have considerable scope for reading their own ideas into the conciliar text. Cardinal Heenan of Westminster mentioned in his autobiography A Crown of Thorns that the Council Fathers were given the opportunity of discussing only general principles:

“Subsequent changes were more radical than those intended by Pope John and the bishops who passed the decree on the Liturgy. His sermon at the end of the first session shows that Pope John did not suspect what was being planned by the liturgical experts.” The Cardinal could hardly have been more explicit.

The experts (periti) who had drafted the text intended to use the ambiguous terminology they had inserted in a manner that the Pope and the Bishops did not even suspect. The English Cardinal warned the Council Fathers of the manner in which the periti could draft texts capable “of both an orthodox and modernistic interpretation.” He told them that he feared the periti, and dreaded the possibility of their obtaining the power to interpret the Council to the world. “God forbid that this should happen!” he exclaimed, but happen it did.

On 26 June 1966 The Tablet reported the creation of five commissions to interpret and implement the Council’s decrees. The members of these commissions were, the report stated, chosen “for the most part from the ranks the Council periti”.

The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy was the first document passed by the Council Fathers (4 December 1963), and the commission to implement it (the Consilium) had been established in 1964.

Triumphant Return

In a gesture which it is very hard to understand, Pope Paul Vl appointed to the key post of Secretary the very man his predecessor had dismissed from the same position on the Preparatory Commission, Father Annibale Bugnini.

Father Bugnini was now in a unique and powerful position to interpret the Liturgy Constitution in precisely the manner he had intended when he masterminded its drafting.

In theory, the Consilium was no more than an advisory body, and the reforms it devised had to be approved by the appropriate Roman Congregation. In his Apostolic Constitution, Sacrum Rituum Congregatio (8 May 1969), Pope Paul Vl ended the existence of the Consilium as a separate body and incorporated it into the Sacred Congregation for Divine Worship.

Father Bugnini was appointed Secretary to the Congregation, and became more powerful than ever. He was now in the most influential position possible to consolidate and extend the revolution behind which he had been the moving spirit and principle of continuity.

Nominal heads of the Consilium and congregations came and went, Cardinals Lercaro, Gut, Tabera, Knox, but Father Bugnini always remained.

His services were rewarded by his consecration as an Archbishop in 1972.

Second Exile

In 1974 he felt able to make his celebrated boast that the reform of the liturgy had been a “major conquest of the Catholic Church”.

He also announced in the same year that his reform was about to enter into its final stage: “The adaptation or ‘incarnation’ of the Roman form of the liturgy into the, usages and mentality of each individual Church.”

In India this “incarnation” has reached the extent of making the Mass in some centres appear more reminiscent of Hindu rites than the Christian Sacrifice.

Then, in July 1975, at the very moment when his power had reached its zenith, Archbishop Bugnini was summarily dismissed from his post to the dismay of liberal Catholics throughout the world.

Not only was he dismissed but his entire Congregation was dissolved and merged with the Congregation for the Sacraments.

Desmond O’Grady expressed the outrage felt by liberals when he wrote in the 30 August 1972 issue of The Tablet:

“Archbishop Annibale Bugnini, who as Secretary of the abolished Congregation for Divine Worship, was the key figure in the Church’s liturgical reform, is not a member of the new congregation. Nor, despite his lengthy experience, was he consulted in the planning of it. He heard of its creation while on holiday in Fiuggi … the abrupt way in which this was done does not augur well for the Bugnini line of encouragement for reform in collaboration with local hierarchies … Mgr Bugnini conceived the next ten years’ work as concerned principally with the incorporation of local usages into the liturgy … He represented the continuity of the post-conciliar liturgical reform.”

The 15 January 1976 issue of L’Osservatore Romano announced that Archbishop Bugnini had been appointed Apostolic Pro Nuncio in Iran.

This was his second and final exile.

Conspirator Or Victim?

Rumours soon began to circulate that the Archbishop had been exiled to Iran because the Pope had been given evidence proving him to be a Freemason.

This accusation was made public in April 1976 by Tito Casini, one of Italy’s leading Catholic writers.

The accusation was repeated in other journals, and gained credence as the months passed and the Vatican did not intervene to deny the allegations. (Of course, whether or not Archbishop Bugnini was a Freemason, in a sense, is a side issue compared with the central issue — the nature and purpose of his liturgical innovations.)

As I wished to comment on the allegation in my book Pope John’s Council, I made a very careful investigation of the facts, and I published them in that book and in far greater detail in Chapter XXIV of its sequel, Pope Paul’s New Mass, where all the necessary documentation to substantiate this article is available.

This prompted a somewhat violent attack upon me by the Archbishop in a letter published in the May issue of the Homiletic and Pastoral Review, in which he claimed that I was a calumniator, and that I had colleagues who were “calumniators by profession”.

I found this attack rather surprising as I alleged no more in Pope John’s Council than Archbishop Bugnini subsequently admitted in La Riforma Liturgica.

I have never claimed to have proof that Archbishop Bugnini was a Freemason.

What I have claimed is that Pope Paul Vl dismissed him because he believed him to be a Freemason — the distinction is an important one.

It is possible that the evidence was not genuine and that the Pope was deceived.

Dossier

The sequence of events was as follows.

A Roman priest of the very highest reputation came into possession of what he considered to be evidence proving Mgr Bugnini to be a Mason.

He had this information placed in the hands of Pope Paul Vl by a cardinal, with a warning that if action were not taken at once he would be bound in conscience to make the matter public.

The dismissal and exile of the Archbishop followed.

In La Riforma Liturgica, Mgr Bugnini states that he has never known for certain what induced the Pope to take such a drastic and unexpected decision, even after “having understandably knocked at a good many doors at all levels in the distressing situation that prevailed” (p. 100).

He did discover that “a very high-ranking cardinal, who was not at all enthusiastic about the liturgical reform, disclosed the existence of a ‘dossier’, which he himself had seen (or placed) on the Pope’s desk, bringing evidence to support the affiliation of Mgr Bugnini to Freemasonry (p. 101).

This is precisely what I stated in my book, and I have not gone beyond these facts.

I will thus repeat that Pope Paul Vl dismissed Archbishop Bugnini because he believed him to be a Mason.

Rumour

The question which then arises is whether the Archbishop was a conspirator or the victim of a conspiracy.

He was adamant that it was the latter: “The disclosure was made in great secrecy, but it was known that the rumour was already circulating in the Curia. It was an absurdity, a pernicious slander. This time, in order to attack the purity of the liturgical reform, they tried morally to tarnish the purity of the secretary of the reform” (p.101-102).

Archbishop Bugnini wrote a letter to the Pope on 22 October 1975 denying any involvement with Freemasonry, or any knowledge of its nature or its aims.

The Pope did not reply.

This is of some significance in view of their close and frequent collaboration from 1964.

The great personal esteem that the Pope had felt for the Archbishop is proved by his decision to appoint him as Secretary to the Consilium, and later to the Sacred Congregation for Divine Worship, despite the action taken against him during the previous pontificate.

Evidence

It is also very significant that the Vatican has never given any reason for the dismissal of Archbishop Bugnini, despite the sensation it caused, and it has never denied the allegations of Masonic affiliation. If no such affiliation had been involved in Mgr Bugnini’s dismissal, it would have been outrageous on the part of the Vatican to allow the charge to be made in public without saying so much as a word to exonerate the Archbishop.

I was able to establish contact with the priest who had arranged for the “Bugnini dossier” to be placed into the hands of Pope Paul Vl, and I urged him to make the evidence public.

He replied:

“I regret that I am unable to comply with your request.

“The secret which must surround the denunciation (in consequence of which Mgr Bugnini had to go!) is top secret and such it has to remain. For many reasons.

“The single fact that the above mentioned Monsignore was immediately dismissed from his post is sufficient.

“This means that the arguments were more than convincing.”

I very much regret that the question of Mgr Bugnini’s possible Masonic affiliation was ever raised as it tends to distract attention from the liturgical revolution which he masterminded.

The important question is not whether Mgr Bugnini was a Mason but whether the manner in which Mass is celebrated in most parishes today truly raises the minds and hearts of the faithful up to almighty God more effectively than did the pre-conciliar celebrations.

The traditional Mass of the Roman Rite is, as Father Faber expressed it, “the most beautiful thing this side of heaven.”

The very idea that men of the second half of the twentieth century could replace it with something better, is, as Dietrich von Hildebrand has remarked, ludicrous.

Liturgy Destroyed

The liturgical heritage of the Roman Rite may well be the most precious treasure of our entire Western civilisation, something to be cherished and preserved for future generations.

The Liturgy Constitution of the Second Vatican Council stated that: “In faithful obedience to tradition, the sacred Council declares that Holy Mother Church holds all lawfully recognised rites to be of equal right and dignity, that she wishes to preserve them in future and foster them in every way.”

How has this command of the Council been obeyed? The answer can be obtained from Father Joseph Gelineau SJ, a Council peritus, and an enthusiastic proponent of the postconciliar revolution. In his book Demain la liturgie, he stated with commendable honesty, concerning the Mass as most Catholics know it today: “To tell the truth it is a different liturgy of the Mass. This needs to be said without ambiguity: the Roman Rite as we knew it no longer exists. It has been destroyed.”

Even Archbishop Bugnini would have found it difficult to explain how something can be preserved and fostered by destroying it.

[End, Michael Davies 1989 piece on Archbishop Bugnini]

Facebook Comments