More than a century ago, Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson foresaw the rise of secular humanism, the contraction of the Catholic Church, and the coming of the Antichrist

By ITV Staff

Editor’s Note: The passage below is from the novel Lord of the World, written by the English Catholic convert Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson (the son of the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury) in 1907. He attempts a vision of the world more than a century in the future — in the early 21st century… our own time… predicting the rise of Communism, the fall of faith in many places, the advance of technology (he foresees helicopters) and so forth up until… the Second Coming of the Lord, with which his vision ends. For this reason, and also because Pope Benedict and Pope Francis have repeatedly cited the book, saying its clarification of the danger of a type of humanitarianism without God is a true danger that we do face, we print a selection from it in ITV, now and in the months ahead.

Lord of the World

By Robert Hugh Benson (1907)

By Robert Hugh Benson (1907)

Book II, The Encounter, Chapter VII, Section I

(Note: The day authorities begin to move against the Faith, Mabel Brand, whose husband is supporter of Felsenbugh — the leader who preaches a humanist future without Christ — takes a moment to pray in a little church. A terrified child runs up, crying “They’re coming! They’re coming!” The persecution has begun. Mabel represents those who are partly deceived by the antichrist; many believe that Benson uses her as a symbol that, even in the worst circumstances, some people may be saved.)

It was nearly sixteen o’clock on the same day, the last day of the year, that Mabel went into the little church that stood in the street beneath her house.

The dark was falling softly, layer on layer; across the roofs to westward burned the smoldering fire of the winter sunset, and the interior was full of the dying light. She had slept a little in her chair that afternoon, and had awakened with that strange cleansed sense of spirit and mind that sometimes follows such sleep. She wondered later how she could have slept at such a time, and above all, how it was that she had perceived nothing of that cloud of fear and fury that even now was falling over town and country alike. She remembered afterwards an unusual busyness on the broad tracks beneath her as she had looked out on them from her windows, and an unusual calling of horns and whistles; but she thought nothing of it, and passed down an hour later for a meditation in the church.

She had grown to love the quiet place, and came in often like this to steady her thoughts and concentrate them on the significance that lay beneath the surface of life — the huge principles upon which all lived, and which so plainly were the true realities. Indeed, such devotion was becoming almost recognized among certain classes of people. Addresses were delivered now and then; little books were being published as guides to the interior life, curiously resembling the old Catholic books on mental prayer. She went today to her usual seat, sat down, folded her hands, looked for a minute or two upon the old stone sanctuary, the white image and the darkening window. Then she closed her eyes and began to think, according to the method she followed.

First she concentrated her attention on herself, detaching it from all that was merely external and transitory, withdrawing it inwards… inwards, until she found that secret spark which, beneath all frailties and activities, made her a substantial member of the divine race of humankind. This then was the first step.

The second consisted in an act of the intellect, followed by one of the imagination. All men possessed that spark, she considered… Then she sent out her powers, sweeping with the eyes of her mind the seething world, seeing beneath the light and dark of the two hemispheres, the countless millions of mankind — children coming into the world, old men leaving it, the mature rejoicing in it and their own strength. Back through the ages she looked, through those centuries of crime and blindness, as the race rose through savagery and superstition to a knowledge of themselves; on through the ages yet to come, as generation followed generation to some climax whose perfection, she told herself, she could not fully comprehend because she was not of it. Yet, she told herself again, that climax had already been born; the birth-pangs were over; for had not He come who was the heir of time?…

Then by a third and vivid act she realized the unity of all, the central fire of which each spark was but a radiation — that vast passionless divine being, realizing Himself up through these centuries, one yet many, Him whom men had called God, now no longer unknown, but recognized as the transcendent total of themselves — Him who now, with the coming of the new Savior, had stirred and awakened and shown Himself as One.

And there she stayed, contemplating the vision of her mind, detaching now this virtue, now that, for particular assimilation, dwelling on her deficiencies, seeing in the whole the fulfillment of all aspirations, the sum of all for which men had hoped — that Spirit of Peace, so long hindered yet generated too perpetually by the passions of the world, forced into outline and being by the energy of individual lives, realizing itself in pulse after pulse, dominant at last, serene, manifest, and triumphant. There she stayed, losing the sense of individuality, merging it by a long-sustained effort of the will, drinking, as she thought, long breaths of the spirit of life and love….

Some sound, she supposed afterwards, disturbed her, and she opened her eyes; and there before her lay the quiet pavement, glimmering through the dusk, the step of the sanctuary, the rostrum on the right, and the peaceful space of darkening air above the white Mother-figure and against the tracery of the old window. It was here that men had worshiped Jesus, that blood-stained Man of Sorrow, who had borne, even on His own confession, not peace but a sword. Yet they had knelt, those blind and hopeless Christians…. Ah! the pathos of it all, the despairing acceptance of any creed that would account for sorrow, the wild worship of any God who had claimed to bear it!

And again came the sound, striking across her peace, though as yet she did not understand why. It was nearer now; and she turned in astonishment to look down the dusky nave. It was from without that the sound had come, that strange murmur, that rose and fell again as she listened. She stood up, her heart quickening a little—only once before had she heard such a sound, once before, in a square, where men raged about a point beneath a platform….

She stepped swiftly out of her seat, passed down the aisle, drew back the curtains beneath the west window, lifted the latch and stepped out.

*****

The street, from where she looked over the railings that barred the entrance to the church, seemed unusually empty and dark. To right and left stretched the houses, overhead the darkening sky was flushed with rose; but it seemed as if the public lights had been forgotten. There was not a living being to be seen.

She had put her hand on the latch of the gate, to open it and go out, when a sudden patter of footsteps made her hesitate; and the next instant a child appeared panting, breathless and terrified, running with her hands before her.

“They’re coming, they’re coming,” sobbed the child, seeing the face looking at her. Then she clung to the bars, staring over her shoulder. Mabel lifted the latch in an instant; the child sprang in, ran to the door and beat against it, then turning, seized her dress and cowered against her. Mabel shut the gate.

“There, there,” she said. “Who is it? Who are coming?” But the child hid her face, drawing at the kindly skirts; and the next moment came the roar of voices and the trampling of footsteps.

*****

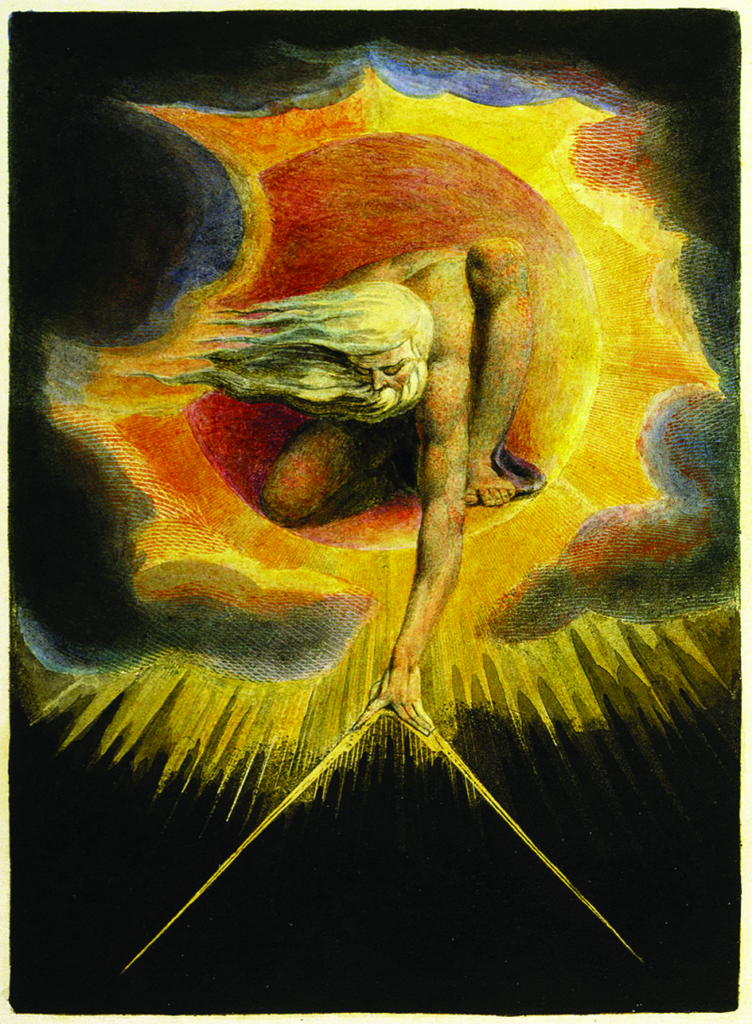

God as depicted by British poet William Blake as the “architect of creation,” now in the British Museum, London

It was not more than a few seconds before the heralds of that grim procession came past. First came a flying squadron of children, laughing, terrified, fascinated, screaming, turning their heads as they ran, with a dog or two yelping among them, and a few women drifting sideways along the pavements. A face of a man, Mabel saw as she glanced in terror upwards, had appeared at the windows opposite, pale and eager — some invalid no doubt dragging himself to see. One group — a well-dressed man in grey, a couple of women carrying babies, a solemn-faced boy — halted immediately before her on the other side of the railings, all talking, none listening, and these too turned their faces to the road on the left, up which every instant the clamor and trampling grew. Yet she could not ask. Her lips moved; but no sound came from them. She was one incarnate apprehension. Across her intense fixity moved pictures of no importance of Oliver as he had been at breakfast, of her own bedroom with its softened paper, of the dark sanctuary and the white figure on which she had looked just now.

They were coming thicker now; a troop of young men with their arms linked swayed into sight, all talking or crying aloud, none listening — all across the roadway, and behind them, surged the crowd, like a wave in a stone-fenced channel, male scarcely distinguishable from female in that pack of faces, and under that sky that grew darker every instant. Except for the noise, which Mabel now hardly noticed, so thick and incessant it was, so complete her concentration in the sense of sight — except for that, it might have been, from its suddenness and overwhelming force, some mob of phantoms trooping on a sudden out of some vista of the spiritual world visible across an open space, and about to vanish again in obscurity. That empty street was full now on this side and that so far as she could see; the young men were gone — running or walking she hardly knew — round the corner to the right, and the entire space was one stream of heads and faces, pressing so fiercely that the group at the railings were detached like weeds and drifted too, sideways, clutching at the bars, and swept away too and vanished. And all the while the child tugged and tore at her skirts.

Certain things began to appear now above the heads of the crowd — objects she could not distinguish in the failing light — poles, and fantastic shapes, fragments of stuff resembling banners, moving as if alive, turning from side to side, borne from beneath. Faces, distorted with passion, looked at her from time to time as the moving show went past, open mouths cried at her; but she hardly saw them. She was watching those strange emblems, straining her eyes through the dusk, striving to distinguish the battered broken shapes, half-guessing, yet afraid to guess. Then, on a sudden, from the hidden lamps beneath the eaves, light leaped into being — that strong, sweet, familiar light, generated by the great engines underground that, in the passion of that catastrophic day, all men had forgotten; and in a moment all changed from a mob of phantoms and shapes into a pitiless reality of life and death.

Before her moved a great rood, with a figure upon it, of which one arm hung from the nailed hand, swinging as it went; an embroidery streamed behind with the swiftness of the motion.

And next after it came the naked body of a child, impaled, white and ruddy, the head fallen upon the breast, and the arms, too, dangling and turning.

And next the figure of a man, hanging by the neck, dressed, it seemed, in a kind of black gown and cape, with its black-capped head twisting from the twisting rope. (to be continued)

Facebook Comments