Why are Catholic Churchmen trying to “dialogue” with Freemasonry?

By Darrick Taylor

Initiation ceremony into Freemasonry in a 19th century print

Freemasonry embodied modern ideas opposed to the Church

When my mother passed away suddenly last summer, the reception for her funeral service was held at the local Masonic Lodge, just down the street from my father’s house. I didn’t think anything of it at the time; I recall seeing portraits of former members, including the father of one of my best friends, who passed away nearly 20 years ago. The rows of portraits of old men, surrounded by the still living old men who operated the lodge, made quite the image.

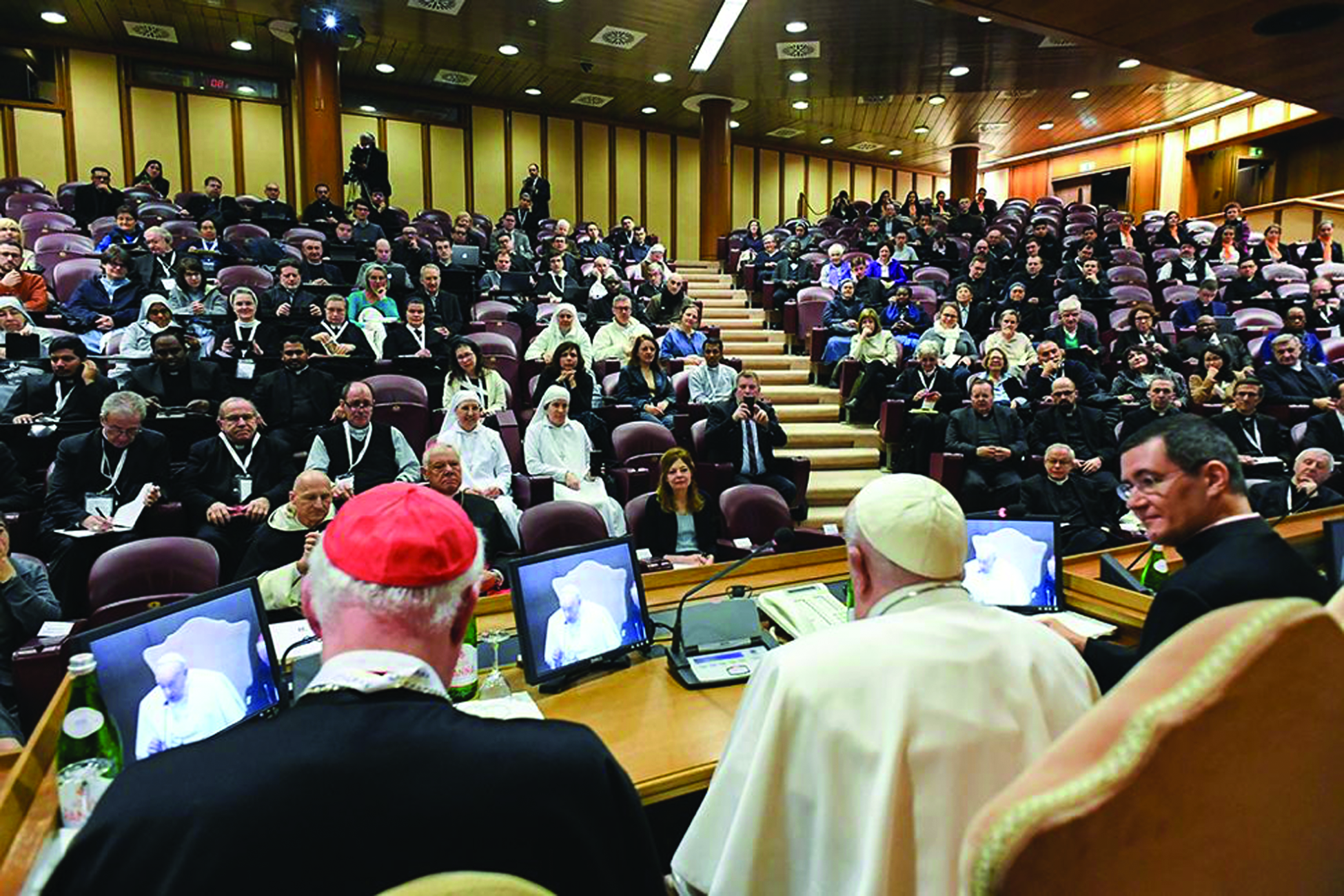

This memory comes to mind when writing about the Vatican’s latest round of (unofficial?) dialogue with the Freemasons of Italy. In November 2023, the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith reiterated the Church’s longstanding assertion that Masonry is incompatible with membership in the Church. But in February 2024 in Milan, a private meeting between heads of the Masonic lodges in Italy and high-ranking Vatican officials took place. The result was confusing: one cardinal, Francesco Coccopalmiero, who took part in the proceedings, called for a “permanent dialogue” with the Freemasons. But then a few days later, Bishop Antonio Stagliano, Pontifical Academy of Theology head who was also present and spoke favorably of the Masons at the meeting, reiterated the Church’s condemnation of Freemasonry. What was going on here?

I confess to never having taken Freemasonry very seriously. To me, it conjures images of old, overweight men in funny hats, engaged in patently silly rituals. Those rituals originated in imitation of Christian ones (the earliest Masonic oaths in the seventeenth century mention defense of the Christian faith), but Masonry became a vehicle for Enlightenment ideals of equality and religious universalism obviously at odds with Christianity. A 1723 constitution spoke of only requiring adherence “to that Religion in which all men Agree,” and though the Masons have always formally excluded atheists from their ranks and never claimed to be a religion, its ideals, if taken literally, are clearly at odds with any notion of special Revelation, and the notion that God has ordained one supernatural religion for mankind, as the Church has always taught. This contradiction is at the bottom of all the numerous condemnations (some 600 or so) of Freemasonry the Church has issued over the centuries.

From its “official” inception in 1717, authorities in both Church and State treated Freemasonry with suspicion because of its secretive rituals, but also because of its egalitarianism in an age of Absolutism, fearing in its lodges a potential 5th column. Part of Masonry’s appeal was its invocation of “reciprocal tenderness and affection” amongst equals, in contrast to the stifling and highly artificial decorum of Absolutist courts. Masonic lodges spoke to a desire to overcome the confessional divide of postReformation Europe, and perhaps represented an expression of masculine “spirituality” in contrast to the perception of a hectoring Mother Church, with its inflexible orthodoxy.

Though long suspected of subversive activities (most of the rebelling American signers of the Declaration of Independence were Masons, for example), there is only one concrete instance that I am aware of in which Masons actually fomented revolution. The Church’s long-standing opposition towards “the Rite” is not fully comprehensible without understanding Masonry’s role in the Risorgimento (1848-1870). The efforts of Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872) and other revolutionaries to unify Italy and overthrow the Papal States were incubated in the Masonic lodges of Italy during the 1830s and after. The Vatican never forgot, or forgave, this overthrow of its authority.

Already Pope Leo XIII, in his Encyclical Letter Humanum Genus of 1884, condemned the philosophical and moral relativism of Freemasonry

Throughout the rest of the nineteenth century, the Vatican issued multiple documents which not only proclaimed that Catholics could not be Freemasons, but that Masons were dedicated to the overthrow of the Church, culminating with Leo XIII’s Humanum Genus (1884). In that document, he declared that Freemasons aimed at “the utter overthrow of that whole religious and political order of the world which the Christian teaching has produced, and the substitution of a new state of things in accordance with their ideas of… naturalism.” Freemasonry had become for the Church a “condensed symbol” of everything about the modern world it despised and wished to combat.

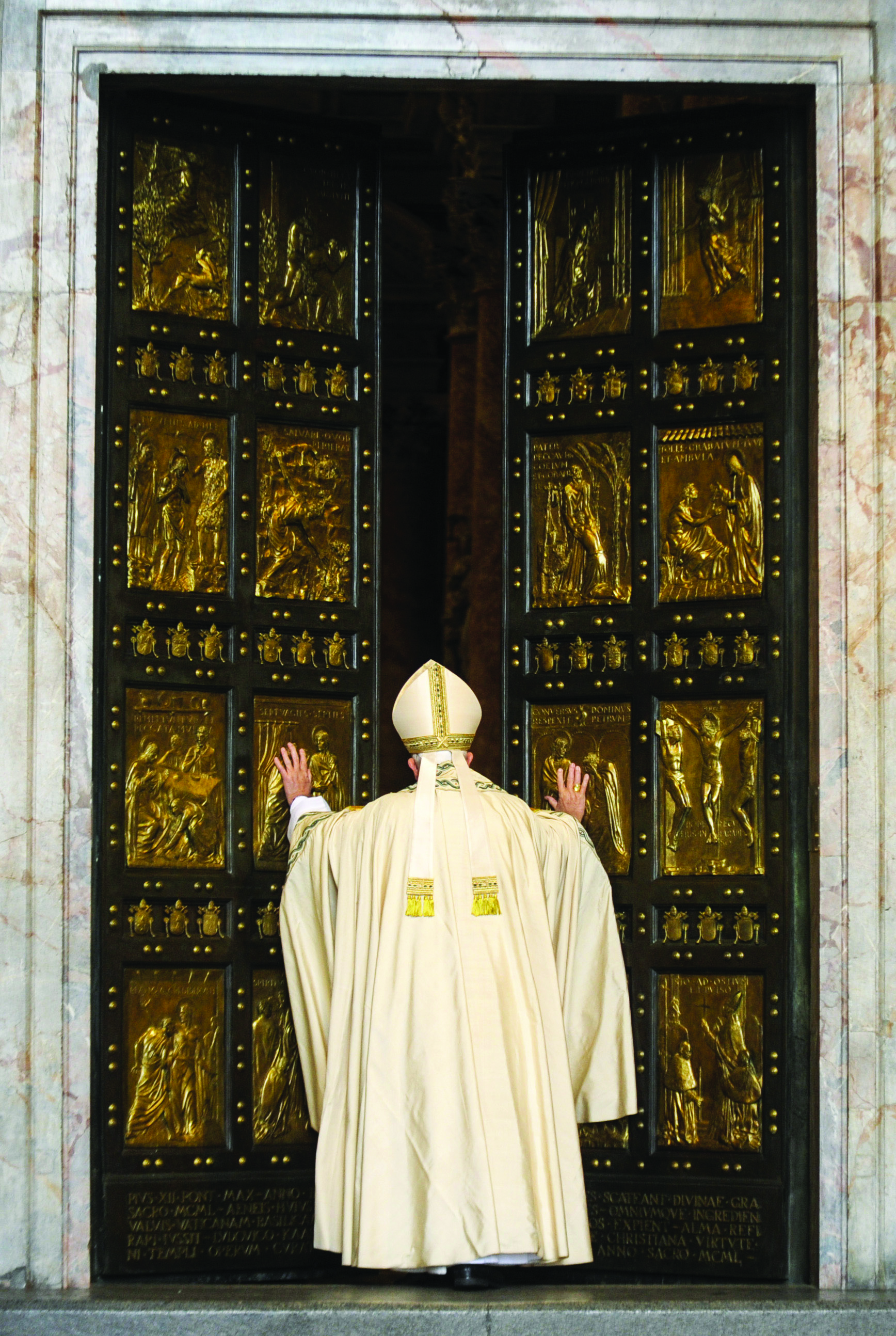

John Paul II tried to curb possible openings to Freemasonry due to post-Vatican II enthusiam for aggiornamento

Until Vatican II, that is. Informal talks between Catholic authorities and representatives of the Freemasons began after that event, and many bishops’ conferences have since said, in effect, that Masonry is harmless. The Vatican under John Paul II tried to rein in much of the enthusiasm for novelty that engulfed the Church after the Council, and in 1983 the CDF, under then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, issued a clarification reaffirming that membership in the Masons was indeed incompatible with Catholicism.

But the current pontificate has for some time now acted as if its two predecessors never existed, and Freemasonry is no exception to that trend.

The current talks with Freemasons in Italy appear aimed, in fact, at reviving the 1970s’ dreams of a “modernized” Church, as in much else. This rubs Catholics of a traditional bent the wrong way, but is in line with the Abu Dhabi statement and many other acts of this pontificate, whose desire to further “human fraternity” and renounce the Church’s attachment to privileges and claims to unique status seems to override all else. And if one is being honest, this began not with Pope Francis but with Pope (now Saint) Paul VI, whose encyclical Ecclesiam Suam (1965) enshrined “dialogue” with the world as almost a dogma of the Church, and whose gestures of humility (such as the abandoning the papal tiara) have been replicated by all of his successors.

But why dialogue with the Masons? If Masonry was once a revolutionary force threatening the Church, it hardly fits that profile today. A cursory internet search reveals that Masonry is in steep decline worldwide; in the 1950s, for example, some four million Americans were members, but that has dwindled to little over a million in recent years, a loss of some 75% of its membership. The Masons are an eighteenth-century organization with an aging, mostly male membership that doesn’t seem, on the surface, to have much of a purpose in the 21st century.

“No absolute truth”: Stefano Bisi, above, was one of three Grand Masters of Italian Freemasonry who met with Church officials, including Milan Archbishop Mario Delpini, in Milan on February 16. He claimed in his remarks that “the bond of brotherhood is independent of faith. It is only necessary to believe in the Great Architect of the Universe… Absolute truths and walls of the mind do not belong to us, and for us they must be torn down”

Masonic ideals represent “permanent 1970” for progressives

Rome’s insistence on dialogue with Masonry is all the more puzzling when one considers the Vatican’s willingness to risk breaking off ecumenical talks with the Orthodox Churches over Fiducia Supplicans.

But perhaps it is not so surprising after all. Whatever their intentions, the actions of the progressive circle surrounding Pope Francis demonstrate that they are much more concerned with reconciling the Church with those aspects of modernity they find appealing, and with correcting what they see as the Church’s past mistakes in that regard, than with maintaining the Church’s ties with the apostolic age — which is why the Orthodox receive such short shrift.

Given their desire to cleanse the Church of its “backwardism,” it makes sense that progressives in the Vatican see the Masons as partners in “dialogue” precisely because the Church for so long saw in them the embodiment of the modern world. Yet it is astonishing to think anyone could convince themselves that the Masons are still representatives of the cutting edge of modernity in the Year of Our Lord 2024.

The progressive party in the Church understands that their efforts to “move the Church forward” can only go so far. They cannot cross certain doctrinal lines without undermining the authority of the Church completely, which is why Fiducia Supplicans makes such a show of not changing doctrine, and which explains why the Vatican dialogues with the Masons — while simultaneously reaffirming the traditional ban on Catholics being Masons.

Thus, all their efforts inevitably take us “back to the future” of the immediate post-conciliar era. The Freemasons are still a “condensed symbol” to the Vatican today, only now they are a symbol of what you might call “Permanent 1970.” For Catholic progressives, their ideal Church is one perpetually on the cusp of a great revolution, so that they can experience the thrill of breaking with the past without having to deal with the consequences of that break, and without having to take responsibility for those consequences.

Facebook Comments