By Lucy Gordan

The first liturgically elaborated Advent wreath was the idea of Johann Hinrich Wichern.

Although Advent falls at the end of our Gregorian calendar year, it marks the beginning of the liturgical year in Western Christianity. The term “Advent” derives from the Latin adventus, meaning “coming” or “arrival.” Thus it’s a time of waiting and preparation, filled with joy but also with repentance and penance. It anticipates the “coming of Christ” from three different perspectives: the nativity in Bethlehem, Christ’s reception in the heart of the believer, and the return of Christ at His Second Coming.

Although Advent falls at the end of our Gregorian calendar year, it marks the beginning of the liturgical year in Western Christianity. The term “Advent” derives from the Latin adventus, meaning “coming” or “arrival.” Thus it’s a time of waiting and preparation, filled with joy but also with repentance and penance. It anticipates the “coming of Christ” from three different perspectives: the nativity in Bethlehem, Christ’s reception in the heart of the believer, and the return of Christ at His Second Coming.

Advent begins on the fourth Sunday before Christmas Day or the Sunday which falls closest to November 30 (thus always between November 27 and December 3), and lasts through Christmas Eve. This year it begins on November 27. In the Catholic Church’s Roman Rite, the readings of Mass on the four Advent Sundays have distinct themes: on the first (Advent Sunday), the anticipation of Christ’s Second Coming; on the second, St. John the Baptist’s preaching; on the third, (Gaudete Sunday), the joy of Christ’s upcoming arrival; and on the fourth, the events involving Mary and Joseph leading up to the Nativity.

It’s not known exactly when Advent was first celebrated, but it certainly existed from about 480. For, according to the historian/bishop St. Gregory of Tours, the celebration of Advent had begun in the fifth century when the Bishop Perpetuus of Tours, who died in 490, ordered that the faithful fast three times a week from St. Martin’s Day, November 11th, until Christmas Day. This rule’s degree of strictness changed several times over the centuries. Finally the Second Vatican Council, in order to differentiate the spirit of Advent from that of Lent, emphasized that Advent was a season of hope—the promise of Christ’s Second Coming.

The Catholic Encyclopedia reports a variation on the origin of Advent, saying that it was a time of fasting and preparation for Epiphany rather than of the anticipation of Christmas, because early converts to Christianity were baptized on the Sunday after Epiphany, the day that commemorates Christ’s baptism. Thus, early-on, Advent lasted 40 days like Lent.

Today’s traditions during Advent are both religious and secular. Some originated as religious and have become less so, and most began in Lutheran areas of Germany. The traditions include praying an Adventthemed daily devotional (a book of Bible verses and prayers for each day of the season), lighting an Advent wreath, lighting a Christingle, performing seasonal music, keeping an Advent calendar, and of course erecting a Christmas tree.

Christingle, in the home version, attributed to Moravian Bishop Johannes de Watteville

It seems that the first Advent wreath dates to 1839 and was the idea of Johann Hinrich Wichern (1808-1881), a Protestant pastor in Hamburg and a pioneer in urban mission work among the poor. Today during Mass on each Advent Sunday, but also at home, candles of different colors are lit on a wreath: the first is purple and called the Prophecy Candle or Candle of Hope; the second, also purple, is the Bethlehem Candle or Candle of Preparation; the third is pink and called the Shepherd Candle or Candle of Joy; the fourth, again purple, is the Angel Candle or Candle of Peace. A fifth candle or Christmas Candle, this time white, is lit on Christmas Day.

It seems that the first Advent wreath dates to 1839 and was the idea of Johann Hinrich Wichern (1808-1881), a Protestant pastor in Hamburg and a pioneer in urban mission work among the poor. Today during Mass on each Advent Sunday, but also at home, candles of different colors are lit on a wreath: the first is purple and called the Prophecy Candle or Candle of Hope; the second, also purple, is the Bethlehem Candle or Candle of Preparation; the third is pink and called the Shepherd Candle or Candle of Joy; the fourth, again purple, is the Angel Candle or Candle of Peace. A fifth candle or Christmas Candle, this time white, is lit on Christmas Day.

Instead, a Christingle, often homemade, consists of an orange representing the world. A candle, today replaced by a glow stick for safety, is pushed into the center of the orange and then lit. It represents Jesus Christ as the “Light of the World.”

A red ribbon wrapped around the orange represents the blood of Christ. In addition, dried fruits and other sweets are often skewered into the orange, representing the fruits of the earth and the four seasons. The Christingle can be traced back to the Moravian Bishop Johannes de Watteville (1718-88), who started this tradition in Germany in 1747.

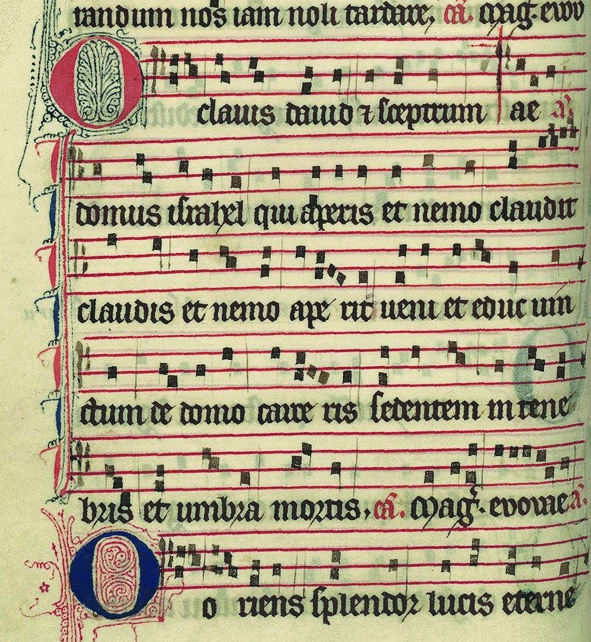

Except for the O Antiphons, also known as the Great Advent antiphons or Great Os, sung at Vespers on the last seven days of Advent (O Wisdom on December 17, O Lord on December 18, O Root of Jesse on December 19, O Key of David on December 20, O Dayspring on December 21, O King of the Nations on December 22, and O With Us is God on December 23) which probably date to sixth-century Italy, much of Advent’s musical repertoire is German. The most famous compositions are Handel’s Messiah (1741) and several Bach (1685-1750) cantatas, which he composed while living in Weimar in 1703 and from 1708-1717 (Nun komm, der heiden Heiland BWV 61 and Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben BWV 147a for examples). He composed only one more (BWV 62, a reworking of BWV 61) in Leipzig where he lived the longest, from 1723 until his death, because there Advent was a silent time which allowed no cantata music except on the first of Advent’s four Sundays.

A page of the O Key of David antiphon from the Latin Catholic liturgy

A collection of pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach for Christmas celebrations

During Advent the Gloria is omitted from Mass, so that only Masses written especially for Advent, such as Missa tempora Quadragesimae in D Minor (1794) for choir and organ by Johann Michael Haydn, the younger brother of the much more famous Franz Joseph, which has no Gloria, was thus suitable.

My memories of the Christmas season as a child in New York City and later as an adult in Rome after I married my Abruzzese husband in 1971, have always included an Advent calendar and a Christmas tree, both of German Lutheran origin. My childhood calendars were made of paper and imported from Germany. Their “windows” opened either onto religious scenes or featured images of toys, angels, musical instruments, or sweets. The numbers for each day were placed arbitrarily so that part of the fun was finding the appropriate day. When I moved to Rome, the most special presents I could bring from New York to my Italian nephews were Advent calendars, which oddly didn’t exist yet in Rome.

From the early 19th century, German Protestants began to mark the days of Advent either by burning a candle each day or by marking walls or doors with a line of chalk each morning. Somewhat later came the practice of hanging a devotional image each day until the first known handmade wooden Advent calendar was created in 1851.

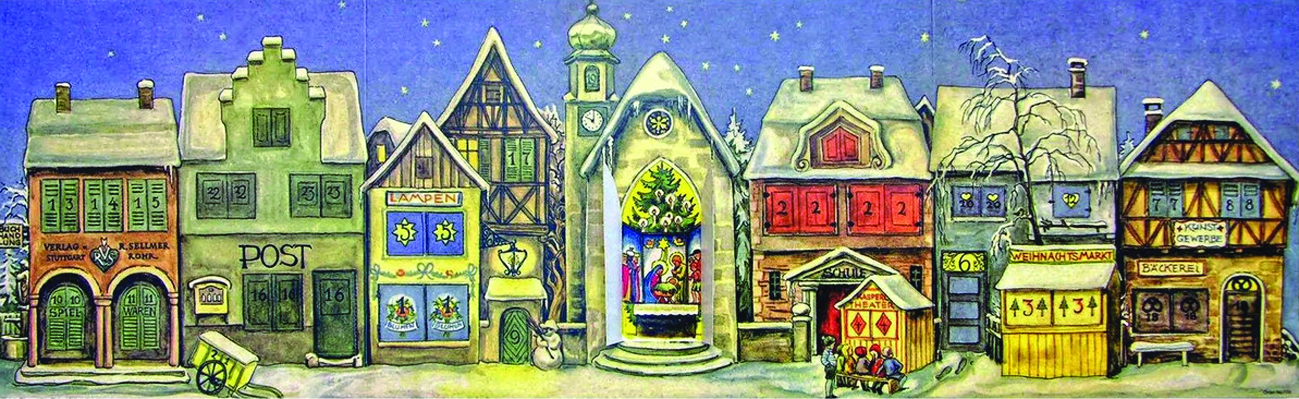

The Little Town,1946, original reprint, German Advent calendar

A Gerhard Lang Advent calendar

The first printed calendars date to the first decade of the 20th century. Since the length of Advent is different every year, to avoid confusion, the calendars customarily begin on December 1 and end on Christmas Eve. German-born Gerhard Lang is considered to be the first printer of Advent calendars with “windows,” but he closed his business when cardboard and paper were rationed just before the outbreak of World War II. In 1943 the Nazis attempted to change Christmas from a religious holiday to a political one, an occasion to praise the Fatherland because Jesus’ Jewish origins grated against the Nazis’ racist ideology. Latching onto the Advent calendar as a way of inculcating loyalty into children, the Third Reich produced a full-color booklet calendar with swastikas and other Nazi symbols which was distributed free to German mothers.

After the war in 1946 Richard Sellmar of Stuttgart received a permit from US officials to begin printing and selling the calendars again, and his company is still their biggest producer today. His first, called “The Little Town,” pictures a winter scene.

President Eisenhower (whose ancestors hailed from Heidelberg, hence the Allies never bombed that city), is credited with popularizing the calendars in the United States after Newsweek published a cover photograph of him in 1953 opening “windows” with his grandchildren.

In 1958 Cadbury, the British chocolate company, added samples in the “windows” and since then many companies worldwide—Godiva, Diptyque scents, Sephora and Occitane beauty products, Bonne Maman jams and honeys, for example—have followed suit. Not a bad marketing move, because, if customers like the sample, they’ll be inclined to buy the full-size version.

In today’s digital world it’s also possible to download virtual Advent calendars with different music, games, quizzes, videos or recipes every day. You can also click on instructions for making your unique one.

The Christmas tree, of Lutheran origin, wasn’t erected in St. Peter’s Square until 1982

As for the Christmas tree, when I first lived in Italy and at least for a decade afterwards, there were no Christmas trees in public squares or private homes, only crèches. The Catholic Church resisted this Lutheran custom, and the first Vatican Christmas tree wasn’t erected in St. Peter’s Square until 1982. Since then, the Vatican trees have been donated by many regions of Italy, Slovenia, Germany, the Ukraine, Belgium, Austria, Croatia, and Romania.

In the United States the Christmas tree became common in the early 19th century. Several cities with German connections lay claim to the first public American Christmas tree: Windsor Locks, Connecticut maintains that the Hessian soldier Hendrick Roddemore, who was captured after the Battle of Bennington, put up a Christmas tree there in 1777 while a POW at the Noden-Reed House, today a museum. Other claims are Easton, Pennsylvania (1816) and Lancaster, Pennsylvania (1821).

Facebook Comments