Stefano Navarrini illustration

By Mother Martha

In early November I received a press release from Sarah Lemieux, the Publicity Coordinator of Sophia Institute Press about its recent publication, The Vatican Christmas Cookbook. It’s the sequel to its best-seller The Vatican Cookbook, which I reviewed in ITV’s August/September 2018 issue.

Both volumes are sponsored by the Pontifical Swiss Guards and The Holy See of the Vatican City State and co-authored by former Swiss Guard David Geisser, one of Switzerland’s leading chefs and TV cooking show hosts. In between these Vatican volumes, Geisser has written three more cookbooks, available only in German.

In this second Vatican volume, Geisser researched and wrote the some 70 recipes (many, perhaps too many, though not unexpectedly, from Swiss and Italian kitchens). His American co-author Thomas Kelly, a resident of Cleveland, wrote the interval texts about the legends, traditions, and history of Christmas in Vatican City and around the world. The images of food are by the Swiss photographer Roy Matter, who has previously collaborated with Geisser on three of his best-selling cookbooks.

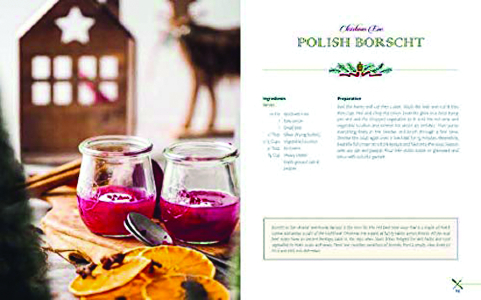

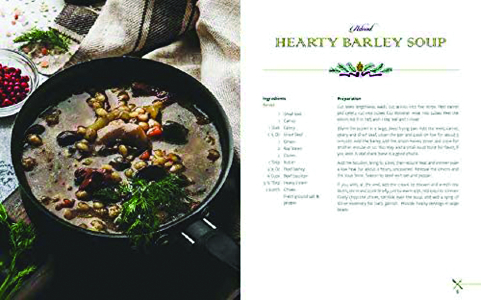

The Vatican Christmas Cookbook, available from Amazon ($34.95), follows the Christmas calendar: Advent, Christmas Eve, Christmas, and Epiphany. Other chapters are “Dishes on the Side” (all featuring potatoes or rice), “The Joy of Fondue,” “Christmas with the Popes,” “Christmas Desserts” (a vast selection, although oddly missing are Panettone, Panforte, Bûche de Noël, Plum Pudding, Gingerbread Houses, and Makowiec), “Christmas Prayers and Graces,” “Christmas Around the World,” specifically on the traditions in Argentina, Egypt, the Philippines, and Switzerland, but including recipes from many countries.

The Vatican Christmas Cookbook, available from Amazon ($34.95), follows the Christmas calendar: Advent, Christmas Eve, Christmas, and Epiphany. Other chapters are “Dishes on the Side” (all featuring potatoes or rice), “The Joy of Fondue,” “Christmas with the Popes,” “Christmas Desserts” (a vast selection, although oddly missing are Panettone, Panforte, Bûche de Noël, Plum Pudding, Gingerbread Houses, and Makowiec), “Christmas Prayers and Graces,” “Christmas Around the World,” specifically on the traditions in Argentina, Egypt, the Philippines, and Switzerland, but including recipes from many countries.

In the introduction, Geisser explains that he included recipes for fondues and fajitas “because these dishes are meant to be shared at the table among friends, family, and guests. These are the best of meals because they encourage and emphasize the human touch.” Then, at the beginning of the chapter “The Joy of Fondue,” he confesses that he couldn’t omit fondue because it’s a Swiss specialty.

Although I would have expected Kelly’s chapter on “Christmas with the Popes” to be longer, he recounts the holiday of only four years: 451 AD, 592 AD, 1919, and 1981.

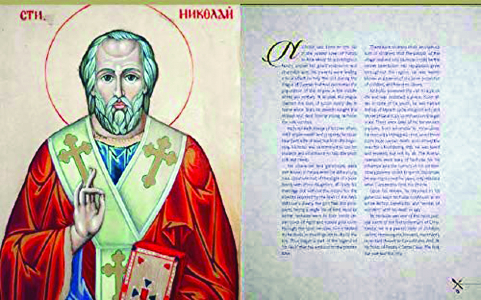

By 451 the ferocious barbarian warrior Atilla the Hun had invaded most of Asia, Eastern Europe, Gaul (today’s France), and northern Italy. Rome was his next objective, even though the Roman Empire was collapsing and the plague and famine had left this once world-dominating city virtually defenseless.

Nonetheless, the fearless Pope Leo I (reigned 440-61), later known as Leo the Great and canonized, traveled with an unarmed delegation of bishops and priests to meet Attila, flanked by his entire army, near today’s city of Mantua. It seems Pope Leo asked Attila for mercy, but there are no official reports of why Attila had a change of heart, withdrew his troops, and retreated to the north. According to legend, during the meeting with Pope Leo, he was shaken by a vision of St. Peter and St. Paul brandishing swords in the sky.

Although I couldn’t find a reason for Kelly’s choice of singling out the Christmas of 592, there’s no doubt that Gregory the Great (Pope from 590 to 604), who had been born into a wealthy and politically powerful Roman family, was one of the most admirable early Popes. Soon after his mother became a nun, he put aside his political career for a life of monastic piety. Although never wanting to be Pope, particularly noteworthy during his reign were his land reforms to support Rome’s poor, and his diplomacy. For example, his closest advisor, the missionary St. Augustine of Canterbury (not to be confused with his more famous namesake, St. Augustine of Hippo) converted the Anglo-Saxons. Not surprisingly, Gregory was canonized quickly after his death. Today he’s best known as a music lover and the promoter of plainsong, later named Gregorian chant.

The chronological gap between 592 and 1919 seems excessive even if the moral fiber of many Popes during the Renaissance and the Baroque was dubious. However, 1919’s Christmas was an appropriate date to celebrate. The First World War had ended the year before and the Spanish flu was de-escalating even if only briefly. (Three years later, Pope Benedict XV (1914-1922) succumbed to the disease.)

Christmas 1981 was certainly a date to celebrate. Pope, now Saint, John Paul II had recovered, if never completely, from Ali Aca’s assassination attempt on May 13 of the same year. All celebrated John Paul’s recovery that Christmas.

Facebook Comments