“Bookseller to the Popes” saw seven papal conclaves in his lifetime

By Andrea Gagliarducci (ACIStampa)

He said that during the conclave of 1963 he put a giant picture of Montini in front of the bookshop, with the certainty that he would be elected Pope. And so it was. But Don Gino Belleri, who was ordained a priest by Giovanni Battista Montini, cardinal and archbishop of Milan, was not only the bookseller of Paul VI, to whom limitless affection and admiration bound him.

He said that during the conclave of 1963 he put a giant picture of Montini in front of the bookshop, with the certainty that he would be elected Pope. And so it was. But Don Gino Belleri, who was ordained a priest by Giovanni Battista Montini, cardinal and archbishop of Milan, was not only the bookseller of Paul VI, to whom limitless affection and admiration bound him.

He had met John XXIII, in one of those daring Vatican stories that could only happen when the Vatican was not rigidly encased in plaster as it is now. And then, he had also had the opportunity to appreciate Albino Luciani (John Paul I), and obviously the long pontificate of John Paul II. Until the arrival of Pope Francis, whom he warned good-naturedly in one of the encounters in which they came face to face.

Don Gino Belleri, 93, died on May 16 in a Roman clinic. For some time he had no longer managed the bookshop, and the pandemic had made his visits to the Vatican rare, if not impossible. He remained alive and vital until the end, continuing to ride a motorbike beyond 80 years of age, when an accident forced him to accede to more cautious advice. And, despite his age, he divided himself between the bookshop and Villa Giuseppina, where he continued to do pastoral service for 60 years for the nuns with serious mental illness who were hospitalized there.

A photo remains of the meeting with Pope Francis, with Don Gino Belleri in a short-sleeved shirt with his finger raised and Pope Francis listening to him, which Don Gino had placed among his “trophies” in the office in the mezzanine of the Librerie Leoniana. A bookstore which, by admission of Joaquin Navarro-Valls, historic spokesperson of John Paul II, had become a “parallel press office,” a fact made even more iconic by the fact that the bookstore was precisely behind the Vatican Press Office, with an entrance on Via dei Corridori which runs parallel to Via della Conciliazione, where the Press Office is.

Don Gino welcomed everyone into his bookshop, and bestowed advice on everyone; for each one he fished out suitable anecdotes from his very precise memory, and with each one he took time to talk, listen and advise. It was not uncommon for a line of people to form in front of his office, including journalists looking for news, priests and bishops looking for books, nuncios and cardinals looking for advice and an exchange of views. It happened once that Archbishop Lorenzo Baldisseri, not yet a cardinal and General Secretary of the Synod, wandered among the shelves of the bookstore while Archbishop Agostino Cacciavillan was in Belleri’s study, and a few scattered journalists were also there, pretending to be interested in books. Among the frequenters of the bookshop was also a president of Italy, Francesco Cossiga, who went there even while he was in office (but continued to live in his house in Prati and not at the Quirinale).

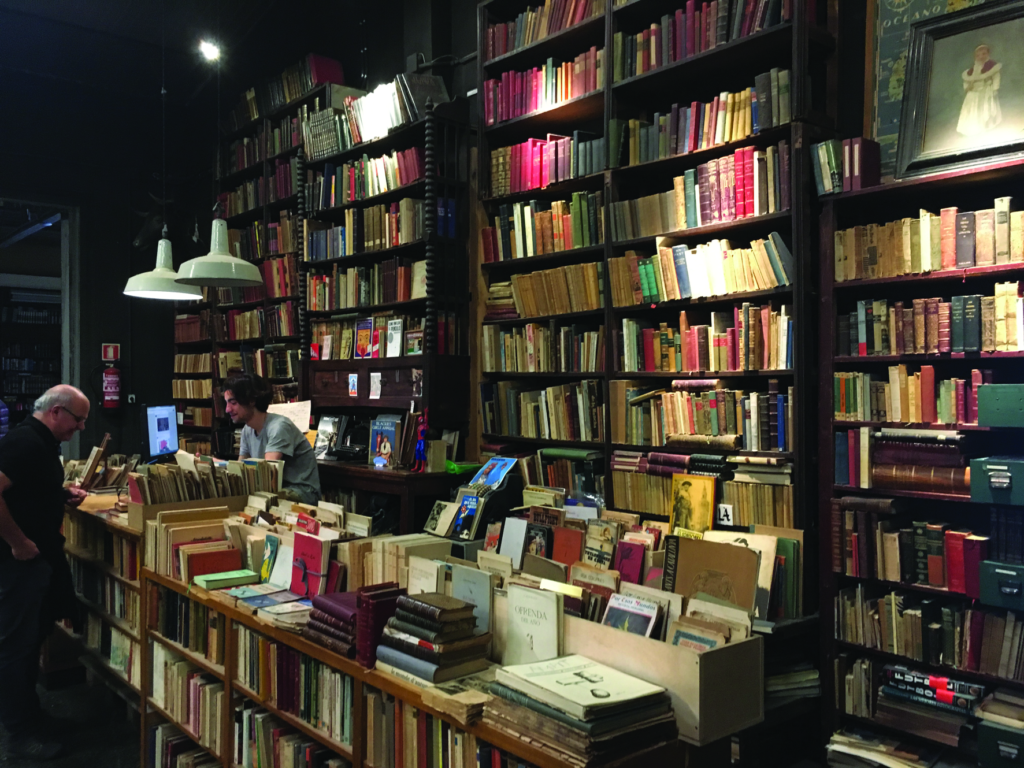

A view of the interior of the Leoniana Bookstore. Below, left, Benny Lai and, right, Gianfranco Svidercoschi, well-known Vatican journalists

In the ferment of the Second Vatican Council (196265), the bookshop became a fundamental landing place for experts and clerics. And from that time on, over the years, Don Gino Belleri became an institution, an icon of a Vatican that no longer exists. A Vatican in which one could still enter without permits when one was a cleric, so much so that Don Gino spoke for the first time with John XXIII when he presented himself there to bring Monsignor Capovilla a book in French that he had requested for the Pope. Capovilla, very busy in who knows what conversation, simply said to him: “You bring it to him.”

In the ferment of the Second Vatican Council (196265), the bookshop became a fundamental landing place for experts and clerics. And from that time on, over the years, Don Gino Belleri became an institution, an icon of a Vatican that no longer exists. A Vatican in which one could still enter without permits when one was a cleric, so much so that Don Gino spoke for the first time with John XXIII when he presented himself there to bring Monsignor Capovilla a book in French that he had requested for the Pope. Capovilla, very busy in who knows what conversation, simply said to him: “You bring it to him.”

From that Vatican, Don Gino had kept the taste for witty jokes, with their neverbanal background and full of meaningful details — a particularly elegant way of managing relationships that was never “over the top.”

In his mezzanine office above the Leoniana Library was his whole life. The photo of his good-natured rebuke to Pope Francis was added to the photo of Paul VI, opening the Year of Faith by lighting a candle, an image he was particularly fond of. And he always sat under a tapestry depicting the Madonna, not very large, of Syrian origin. Always in the dim light, with only the yellow rays of a lamp illuminating it, Don Gino kept a sentence from Seneca in De Brevitate Vitae stuck on a Post-it note in his tiny and somewhat disordered handwriting, for the benefit of those who read it: “Non exiguum tempus habemus, sed multum perdidimus” — “We do not have too short a time, but we waste most of it.”

Don Gino certainly wasted no time, giving to many previews of important documents, such as some of the papal encyclicals. Through him also filtered the news of the correspondence between Cardinal Silvio Oddi and the would-be assassin of John Paul II, Ali Agca.

Don Gino Belleri was also a great friend of Cardinal Giovan Battista Re, current dean of the College of Cardinals, and it was perhaps for this reason that then-Archbishop Emmanuel Milingo decided to tell him about his decision to marry the Korean acupuncturist Maria Sung of the Reverend Moon sect. Re was at the time Prefect of the Congregation of Bishops, and had to manage a situation that was certainly not easy.

Yet, Don Belleri was above all a good man, who knew and helped the poor who were stationed around his bookshop and St. Peter’s, and knew how to be generous. And it was precisely his human figure, almost unsuspected, that attracted the friendship of many.

And here this reporter must now leave room for a friend, and move on to telling the story in the first person. Don Gino Belleri was introduced to me by Benny Lai, the dean of the Italian Vaticanists, who was introducing me to the profession, and who immediately wanted to show me the “parallel press office.” Don Gino welcomed us into his office after a brief wait in his anteroom, and Benny Lai told me that whatever Don Gino would say to me, it would be as if he had said it.

Thus began an acquaintance, at first timid and then more and more assiduous. I filled notepads with notes of the things he told me. I used his anecdotes for a column I had on Sicily, and I also learned to understand where the news he was referring to me came from, gradually understanding how to filter it and when I could totally rely on it.

It was a real school of pontifical languages, slow, constant, discreet, never invasive, always respectful of the ardor of my 20 years. A type of school that no longer exists, just as the Vatican of Don Gino Belleri and Benny Lai no longer exists.

It was the Vatican of a whisper, a Vatican which knew how to communicate news in low tones, and which had a profound sense of being an “institution.” And Don Gino, who was also strongly a priest of the Second Vatican Council and whom no one could accuse of conservatism, loved precise language — just as precise as the Latin that he had mastered perfectly.

He was a bookseller because he loved being among books, he was a priest because he loved being a priest, he was a friend because he simply couldn’t do otherwise. And to him I also owe another friendship, the one with Gianfranco Svidercoschi. Benny Lai took me to Don Gino, Don Gino sent me to Svidercoschi. It was like this, one step at a time, that young people were ushered into the Vatican corridors. Rooms you seldom can enter today, but the secrets of which everyone seems convinced they know how to interpret and explain.

For this reason, with Don Gino goes one of the last citizens of a Vatican world that no longer exists. It is not a nostalgic statement. It is an observation that must help us to understand the times.

Facebook Comments