Jesus knows the evil in every heart, yet He will defend each of us

By Anthony Esolen

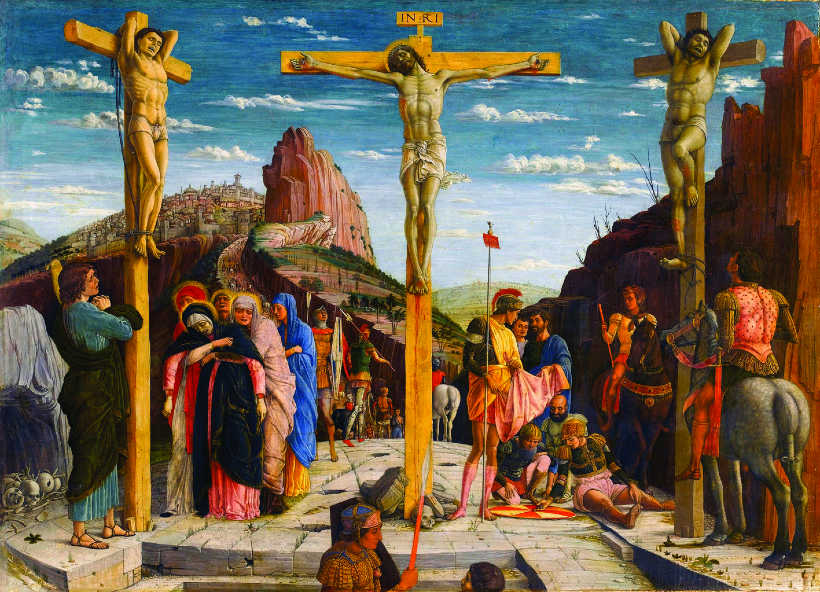

The Crucifixion painted by Andrea Mantegna for the altar of San Zeno in Verona (Italy).

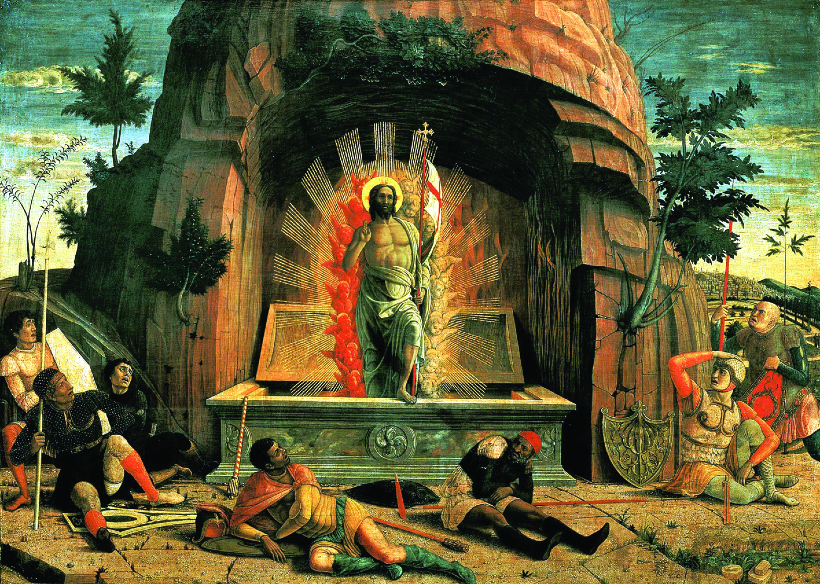

The Resurrection painted by Andrea Mantegna. It is a panel now in the Musee des Beaux-Arts in Tours (France)

One of the saddest verses in Scripture comes to us from Saint John, who says that Jesus performed many wonders in Jerusalem after He had gone there for the Passover, and many began to believe in His name. “But Jesus did not trust Himself to them,” says John, “because He knew all men and needed no one to bear witness of man, for He Himself knew what was in man.” (Jn. 2:24-25)

The version that Catholics in the United States will hear blunts the power and the personal challenge that Jesus implicitly makes to us in those words. Here is how the translators of our lectionary render them: “But Jesus would not trust Himself to them because He knew them all, and did not need anyone to testify about human nature. He himself understood it well.”

We too understand it well — I mean that we understand why the translators have done what they have done. They are prompted by a childish desire to avoid using the word “man” in its universal, personal, singular sense. Since there is no substitute for it in English, no word that does that same work, they are content to flail about and let the Scripture be muffled.

Let me explain. The Revised Standard Version above says that Jesus “knew all men,” not just that He “knew them all.” The Greek could be taken either way, but most translations follow the sense of the whole statement and interpret John as saying that Jesus knew all men, and not just the hapless people who for a time believed in Him because of His miracles.

The real trouble comes in the final verse, after “all” or “all men.” Let us imagine a scene. You are charged with being man: weak, cowardly, selfish, treacherous man. Someone comes forth as a witness against you. He accuses you of looking the other way when your friend is treated unjustly. He accuses you of listening to the shouts of the mob and not to the admonitory voice of God in your conscience. He accuses you of forgetting your benefactor when it is convenient for you to forget. He accuses you of pretense in the service of your own gain.You are in the dock. How do you reply?

This is a great deal more than, and something other than, the “human nature” that the timid translators have used for the Greek anthropos, man. It is other than “human nature” because although we are fallen and can say with the Psalmist, “In sin did my mother conceive me” (Ps. 51:5), this fallen nature is and is not really ours. It is ours, just as a hunched back or a club foot belongs to someone born a cripple. It is not ours, because we were not meant to be so. We were not meant to be hunched over in sin — incurvatus, to use Augustine’s fine term. Our redemption and sanctification will make us more human, not less, giving us a more profound share in the human nature that God intended for us to enjoy.

It is more than “human nature,” because we are not talking about general tendencies, spread across a large population. We are talking about man, and that means John, Peter, Nicodemus, Mary and her sister Martha, Judas, Caiaphas, Pilate, Saul of Tarsus, you, me, and the barber down the street. It means each one of us, with painful singularity. There is nothing comfortably and vaguely general about it. Jesus did not need the witness for the prosecution. He knew already—He knows already— what is in man.

There is a play on words in the Greek that does not come across in either translation, because English will not allow it. Jerome’s Latin did allow it: “Multi crediderunt in nomine ejus,” “many believed in His name,” but “Iesus non credebat semetipsum eis.” Maybe we could think of the parallelism in this way: “Many trusted in his name, but Jesus did not entrust himself to them.” That would preserve the ironic reversal, though we would lose a fuller sense of “believing” than “trusting” implies. In any case, we see here what I might call the fundamental dramatic irony of the Gospel.

Jesus does not “believe in” man. Nowhere in his words do we find any sentimental approbation of natural human goodness. On a human level, His expectations are low, and most of the time the people to whom He preaches fail to meet even those. “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, killing the prophets and stoning those who are sent to you!” He cries. “How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you would not!” (Mt. 23:37) Yet this same Jesus does hand Himself over to men, to be condemned and put to death upon Golgotha. He does it with full knowledge of what will happen. But that is not the end. He rises; and in the Sacrament of the Altar He hands Himself over to men again and again, that they too might rise to eternal life. He does not believe in us, as the humanist pretends to do, and the humanist is ever one genuine encounter with man away from misanthropy. Jesus knows very well what is in each of us, and that makes His entrusting Himself to us all the more telling an act of love. And those who entrust themselves to Him in return arise with Him, and take on His nature, becoming holy even as He is holy, and saying, justly, “I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me.” (Gal. 2:20)

Then we sinners shall have someone to intercede for us, to be our defense attorney, bearing witness: “Christ has entered, not into a sanctuary made with hands, a copy of the true one, but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God on our behalf.” (Heb. 9:24)

Anthony Esolen, Ph.D., is a faculty member and Writer-in-Residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts in New Hampshire. Dr. Esolen is a renowned scholar and translator of literature, and an author of multiple books and hundreds of articles in both Catholic and secular periodicals.

Facebook Comments