So Caravaggio Escaped… To Naples

By Lucy Gordan

Nicola Malinconico’s Good Samaritan.

Battistello’s Noli Me Tangere

The recently-restored Young St. John the Baptist

On May 29, 1606, during a brawl in Piazza Navona in Rome, the artist Caravaggio (1571-1610) murdered the pimp from Terni Ranuccio Tomassoni, who had VIP clients: nobles, notaries, cardinals. The painter was sentenced to death. To avoid papal justice, this hot-headed and often violent master of chiaroscuro escaped to Naples, outside the jurisdiction of Rome’s authority, where he could count on the protection of the powerful Colonna family.

Thus the most famous painter in Rome became the most famous painter in Naples. During his first stay, from October 1606 to June 1607, he painted numerous masterpieces. These included the breathtaking altarpieces with the Seven Works of Mercy for the Pio Monte and the Flagellation (now in Naples’ Capodimonte Museum) for the Church of San Domenico.

Like his Roman canvases, these works are characterized by the intense naturalism of their human figures and of light, and by an unprecedented, seemingly irreverent interpretation of sacred themes because his models were frequently his tavern companions, beggars, and prostitutes. The most famous painting of Caravaggio’s second stay in Naples, from October 1609 to July 1610, during which time his face was badly disfigured in yet again another brawl, is his dramatic Martyrdom of St. Ursula, his last work (now in Naples’ Baroque Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano, at Via Toledo 185, an art museum since 2014).

On until April 13 in Prato, an off-the-beaten-track Tuscan city, in the Palazzo Pretorio, is Dopo Caravaggio: Il Seicento Napoletano in Mostra a Prato or “After Caravaggio: 17th-Century Neapolitan Art Exhibit in Prato.” As the title clearly states, the exhibition is not about Caravaggio, but about the painters, his contemporaries and others of the next two generations, who lived in Naples, studied his Neapolitan, and sometimes Roman, works, and were deeply influenced by his style and subject matter.

Sixteen of the 19 paintings, never exhibited publicly before, belong to the Fondazione De Vito, and the other three to the Civic Museum in Prato’s Palazzo Pretorio, home to Tuscany’s second most important collection of 17th-century Neapolitan paintings after the Uffizi. The three are Battistello’s Noli Me Tangere (1618), Mattia Preti’s Repudiation of Hagar (c. 1635-1640), and Nicola Malinconico’s Good Samaritan (1703-6), the exhibition’s final painting. Malinconico (Naples, 1663-1721) was a student of Luca Giordano, protagonist of the Neapolitan baroque. The Good Samaritan’s brilliant colors, its softness and the freedom of its brushstrokes are thanks to Giordano, but its subject had been painted by Ribera.

The Fondazione De Vito, headquartered at the Villa degli Olmi, Via della Casa al Vento 1774, in Vaglia, a picturesque hamlet 20 km. north of Florence, was founded in 2011 by Giuseppe De Vito (Portici, a neighborhood of Naples, 1924-Florence, 2015). He was a successful engineer, scholar, collector of 17th-century Neapolitan art, and in 1982 founder of the scholarly journal Ricerche sul ‘600 napoletano, still published annually with the updated title of Ricerche per la storia dell’arte moderna a Napoli. The foundation seeks “to promote studies on the history of Modern Art in Naples with exhibitions, seminars, conferences, publications, and scholarships for students.” Its headquarters house De Vito’s 60 paintings and a library. Scholars can visit by appointment: [email protected], tel. +39-055-549811.

De Vito’s collection of 17th-century Neapolitan paintings, perhaps the most significant in private hands, includes works by Giovanni Battista Caracciolo, nicknamed “Battistello,” Jusepe de Ribera, and many others. Very few of De Vito’s paintings have ever been exhibited publicly and, before Prato, only with De Vito’s direct intervention.

Prato’s show, displayed in chronological order, is divided into four parts: “Giovanni Battista Caracciolo 1618-35,” “Jusepe De Ribera and the Master of the Annuciation to the Shepherds 1632-1650,” “Female Protagonists 1634-1652,” and “Mattia Preti and the Second Half of the Century.” It opens with two paintings by Battistello: the recently-restored Young St. John the Baptist and the Noli me tangere of Prato’s Museum. The latter, painted in 1618, when Battistello was in Florence at the Medici court, is considered his masterpiece.

Battistello (Naples 1578-1635) is the only painter on exhibit to have met Caravaggio in person, probably around the time of Caravaggio’s Radolovich commission in 1606. Battistello was also among the first to adopt Caravaggio’s startling new style of chiaroscuro with its human figures defined by spotlight. His Immaculate Conception for the Church of Santa Maria della Stella in Naples is considered to be the first documented Caravaggesque painting. In stylistic and thematic relationship with these two paintings is Massimo Stanzione’s St. John the Baptist in the Desert, datable to c. 1630. Again the saint is depicted as a youth with a lamb. Stanzione (Naples 1585-Naples 1656) was the arch-rival of Spanish-born (in Xàtiva near Valencia) Jusepe de Ribera.

Ribera is the subject of the exhibit’s second section together with his pupil, also born in Xàtiva and known as “The Master of the Annunciation to the Shepherds.” De Vito identified him as Juan Dò (1617?-1656?). Battistello and Ribera were witnesses at Dò’s marriage to Grazia, the sister of fellow-painter Pacecco De Rosa, who was a pupil of Stanzione.

Stanzione and Ribera, who was active in Naples from 1616 to his death in 1652, both dominated the painting scene in Naples for several decades, depicting primarily religious subjects. Ribera was the most important painter for the development of Caravaggesque naturalism. He moved from Spain to Rome in 1612 where he lived on Via Margutta, joined the Academy of St. Luke, and collaborated with other foreign admirers of Caravaggio. In 1616 he moved to Naples to avoid his creditors and there married Caterina, daughter of the Sicilian-born Neapolitan painter Giovanni Bernardino Azzolino, who introduced Ribera to the Neapolitan art world.

Jusepe de Ribera’s St. Anthony Abbot.

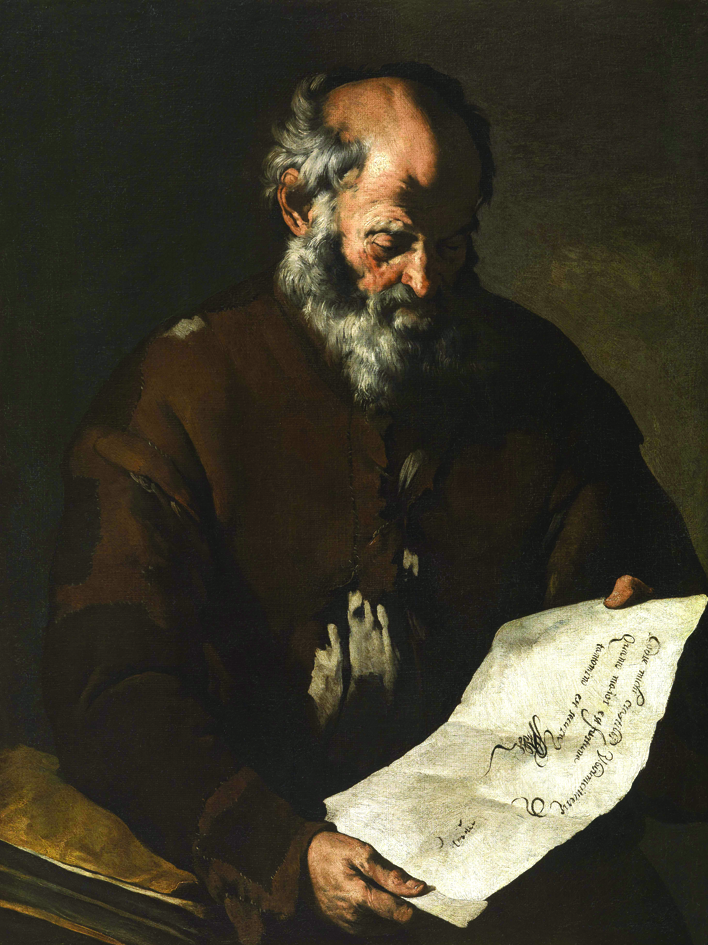

Juan Dò’s Old Man in Meditation with a Cartouche

Young Man Smelling a Rose

Ribera soon headed a workshop with numerous pupils and collaborators. In addition to sacred scenes, he painted half figures of saints and philosophers. His St. Anthony Abbot (1638), on display here, is an almost photographic portrait, very similar to many of Caravaggio’s saints, especially his two of St. Mark (one destroyed during World War II) in Rome’s Church of San Luigi dei Francesi.

On the same wall with St. Anthony Abbot are three portraits with philosophical themes by Ribera’s student Juan Dò. Man in Meditation in Front of a Mirror (1640-45) is identifiable as a Socratic philosopher. Old Man in Meditation with a Cartouche (1648-52) has a Latin inscription about the transience of material goods and life itself. The realistic, wrinkled, low-class faces of both these half-length portraits are Caravaggesque. Less so in appearance, but not thematically, is Dò’s Young Man Smelling a Rose, also an allegory of the transience of life. Moreover, in appearance this Young Man (the exhibition’s logo) seems sickly like many of Caravaggio’s portraits of musicians and of Bacchus. Section 2 ends with a half-length portrait of a Prophet (1640-45) by Francesco Francanzano (1612-1656), another student of Ribera. Francanzano’s portrait is similar to Dò’s two older philosophical men, grizzly in appearance, but the Prophet’s cartouche is blank, awaiting divine inspiration.

The canvasses of Section 3, painted in the 1640s and 1650s, are still Caravaggesque with the protagonists spotlighted, but their brighter and greater variety of colors show a new Venetian and Flemish influence — a major turning point. Moreover, their subjects are female, not male, protagonists from the Old and New Testaments and female martyrs, Catherine, Ursula, Lucy, and Agatha, very popular saints in 17th-century Neapolitan painting. The spotlighted saint in The Martyrdom of St. Ursula (1634-6) by Neapolitan Giovanni Ricca (1603-1656?) is similar to Caravaggio’s painting of the same subject in Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano. Likewise is St. Agatha (c. 1636-40) by Antonio Vaccaro (Naples, 1604-70). The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine (1635) by Neapolitan Paolo Finoglio (1590-1645) shows an affinity to the light and layout of the Nolo Me Tangere by Battistello. In contrast, St. Lucy (1645-8) by Neapolitan Bernardo Cavallino (1616-56), who is said to have trained with Stanzione and worked with Francesco Francanzano, has a softer diffused light and brighter colors, including a Venetian red curtain.

Section 4 centers on four works by Calabrian Mattia Preti (1613-1699). He trained in Rome before living in Naples from 1653 to 1660. He helped bring Caravaggio’s naturalism into a fully Baroque style. His Repudiation of Hagar was painted in Rome and was heavily influenced by Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro. Prato is only a 20-minute train ride from Florence. It is worth a detour.

Facebook Comments