By James Bogle

Pope St. Leo III crowns Emperor Charlemagne in St. Peter’s Basilica in 800 A.D. (by Friedrich Kaulbach)

A cursory glance at the references to the Pope in any article on, say, Wikipedia, but also in very many other media sources, will reveal the frequency with which it has become customary for writers, bloggers and journalists to refer to the Pope as the “Head of the Catholic Church.”

It reveals a deep failure to understand the nature of both the Papacy and the Catholic Church.

Yet one can now find even Catholic journalists making this same mistake.

The Pope is not now, and never has been, the “Head of the Catholic Church”, save in a derivative sense.

There is only one true “Head of the Catholic Church” and that is our Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ.

He, and He alone, is the true “Head of the Catholic Church” …but he delegated His earthly spiritual authority to St Peter, and his successors, the popes, to govern the visible Church upon earth as a visible, earthly, spiritual “head” lest the Church be left spiritually leaderless and doctrinal and disciplinary issues be left unresolved.

This fact is rarely mentioned by journalists because many of them (even some Catholics) believe that the Church is a purely human institution with a purely human “head”.

The Pope is, as his age-old title reminds us, the “Vicar of Christ,” i.e., a kind of “prime minister” of Christ.

Moreover, the Pope is only the spiritual Vicar of Christ. He is not the temporal Vicar of Christ.

In the ages of faith, indeed, right up until Napoleonic times, every Catholic knew that the temporal Vicar of Christ was the Emperor (or, more fully, the Holy Roman Emperor) and he was treated as such by the Church and by every Pope that reigned in those days.

Indeed, he was prayed for on Good Friday, and at the Easter Vigil, directly after the Pope and clergy, right up until those imperial prayers were removed by Archbishop Bugnini in 1954.

It is an oft-forgotten fact that the Popes were purely temporal subjects of the emperors for most of Christian history.

The Papal States had been “feued” (granted) to Pope Stephen II, in 756, by King Pepin the Short, the father of an emperor, Charlemagne, who later confirmed the same.

Thus it remained until the very end of the Empire in 1806, when it was effectively dissolved by Napoleon Bonaparte, the destroyer of old Christendom.

True, the Popes became virtually independent from about 1300 but, even then, they were still, technically and legally, temporal subjects of the Emperor and acknowledged themselves to be such. Even the Duchy of Rome, which the Popes occupied prior to the so-called Donation of Pepin, was a territory feued from the Eastern Emperor.

It was on Christmas Day 800 AD that the nobility, clergy and freemen of the City of Rome transferred their allegiance from the Eastern Emperor (actually Empress Irene) and, by acclamation, elected (as was the traditional method of choosing emperors, just as Popes) Charles, King of the Franks, to be the renewed Emperor of the Romans in the West, Caesar semper Augustus et Imperator.

This was with the blessing of Pope St. Leo III who then crowned him in St Peter’s Basilica as we are told by Einhard, the chronicler of the life of Charlemagne in his Vita Caroli Magni.

Pope St. Leo III had given his blessing to this translatio imperii (transfer of the imperial power) not only because of the failure of the Eastern empress, Irene, to come to the aid of the Popes, under constant threat from the Lombards, in contrast to Pepin and the Franks, but also because she had usurped the imperial throne from her own son, Constantine VI, and connived at his blinding, from which assault he had died.

In a proper approach to the distinction between clerical and lay power, advice and blessing was first sought from the spiritual Vicar of Chris, Pope Leo III.

It was necessary to gain the papal sanction since emperors, after election, were required to be crowned and consecrated by the Pope, or his delegate. But this was virtually assured as Pope Leo had already sought assistance from King Pepin and from his son, Charlemagne, and had already condemned the usurpation of the imperial throne by Empress Irene.

It was necessary to gain the papal sanction since emperors, after election, were required to be crowned and consecrated by the Pope, or his delegate. But this was virtually assured as Pope Leo had already sought assistance from King Pepin and from his son, Charlemagne, and had already condemned the usurpation of the imperial throne by Empress Irene.

The nobility, clergy and freemen of the City of Rome had, since early times, always elected both Pope and Emperor, but since free elections often occasioned violence and bloodshed, the privilege of electing Popes and emperors eventually (by the early Middle Ages) devolved upon two electoral colleges (the origin of an idea still used in American presidential elections).

The two electoral colleges were, for Popes, the College of Cardinal-princes and, for emperors, the College of Prince-electors, originally seven in number, being the King of Bohemia, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg, the Count-Palatine of the Rhine and the three archbishops of Mainz, Cologne and Trier.

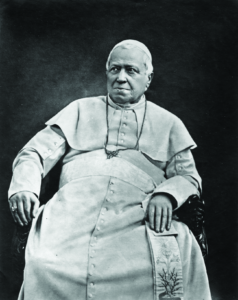

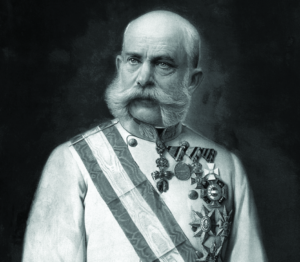

St. Pius X and Blessed Pius IX (above), both elected to the Petrine office after exercise of the imperial veto by the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I

However, the position of the Pope was fundamentally different from any other temporal subject because he was (and is) spiritually superior to the Emperor (even if temporally inferior) by virtue of being the spiritual Vicar of Christ and successor of St. Peter, and because the spiritual power, or power of conscience, is, in its own sphere, superior to the purely temporal power.

This constitution, or blueprint, for Christendom had been long before laid down, originally by Christ Himself, but was expressly reiterated by Pope St. Gelasius I in his famous letter Famuli Vestrae Pietatis (sometimes called Duo Sunt) addressed to the Eastern emperor, Anastasius I Dicorus.

It delineated the two powers that rule the Christian world, namely the spiritual and the temporal, the Pope and the Emperor. This remained the blueprint for Christendom until the fall of the Empire, 1300 years later.

It is also often forgotten that the expression “the Church” does not mean merely the clergy of the Catholic Church as is also frequently fondly supposed.

The Church is the whole body of the Faithful, lay and clerical, secular and religious.

And therein lies another common fallacy: the antonym of “clerical” is “lay” and the antonym of “religious” is “secular” but you will often find the terms muddled, particularly in the minds of non-Catholics.

There are religious laymen and religious clerics, just as there are secular clergy and secular laity (the latter being the majority of the Church).

But a “secular religious” or a “lay cleric” are contradictions in terms.

In his quite astonishingly ill-informed book, The Case of the Pope, hostile anti-Catholic writer, barrister and judge, Geoffrey Robertson, QC, describes a “deacon” as a kind of monk, betraying an ignorance of the simplest religious concepts in Catholicism.

After the fall of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, a “rump” of the Empire continued as the Austrian Empire for another 112 years until 1918, when it was dissolved by the victors of the First World War.

The Austrian Emperor retained the imperial veto over Papal elections (as did the kings of Spain and France) almost to the end, and it is worth remembering that, by exercise of the imperial veto, two saints came to the pontifical throne, St. Pius X and Blessed Pius IX, both elected to the Petrine office after exercise of the imperial veto by the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I.

Once the empires had fallen, the position of the lay counterpart to the Pope became uncertain, unresolved and confused.

Indeed, the whole issue of the lay vocation became an issue of much discussion in a way that it never was when there were kings and emperors and the position of lay power in the Church was obvious.

Our time has seen a huge increase in clerical power in the Church, and a vanishing of the lay power, with consequences that have often been far from beneficial.

Lord Acton used to say that “power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Whether or not this is true, the absolute power now enjoyed by the clergy in the Church has not been any more beneficial than other forms of absolute power.

One of the other consequences has been that journalists now persist in referring to the Pope as “the Head of the Catholic Church” usurping a position that belongs only to Jesus Christ, our Lord, and to Him alone.

James Bogle is a barrister, writer, historian, former British army officer and past president of the International Una Voce Federation.

Facebook Comments