Young people hold up a sign that reads “We love Jesus” as they gather for an outdoor Mass with Pope Benedict XVI on the waterfront in Beirut on September 16, 2012 (CNS photo/Mohamed Azakir, Reuters).

Here, the Shrine of Our Lady of Lebanon in Harissa, east of Beirut. (CNS photo)

By Christopher Hart-Moynihan

“In Lebanon, the message must be the looming possibility of global famine.”

— A friend, summarizing the message of the Lebanese Global Conference, held on April 26 in Washington, D.C., as concern grows over the rising price of food and fertilizer in Lebanon and throughout the Middle East and beyond

“Many of the Christian political leaders in Lebanon are for power. We don’t trust them. We don’t have true Christian leaders. Only Patriarch Raï. He should go to the United Nations [to advocate for Lebanon] with the Sunni and Druze. Only the Shia are happy with the present situation.”

— a Lebanese participant in our Unitas: Friends of Lebanon video conference, sponsored by Urbi et Orbi Communications on Friday, April 29

Despite sectarian conflict, a devastating explosion and economic collapse, Lebanon remains “a message of freedom and pluralism” for the world

After several years of anticipation, it seemed to be all but a formality: a Pope would be visiting Lebanon for the first time since 2012.

Then came a flurry of statements from sources in the Curia that rolled back the travel plans. Now Pope Francis’s visit to Lebanon is once again at the stage where it had remained for quite some time: slated to happen sometime “very soon,” though nobody is quite certain when.

The first news about a papal visit in June was, in fact, not released by the Vatican, but rather by the office of the President of Lebanon, which put out a statement on Tuesday, April 5. In it, they announced that Pope Francis would be coming to Lebanon on June 12-13.

According to the statement, news of the Pope’s visit had been confirmed by Archbishop Joseph Spiteri, the Apostolic Nuncio to Lebanon. However, Matteo Bruni, the director of the Holy See Press Office, characterized the June trip as simply “a possibility that is being studied.”

Then, in May, first the Vatican and then the Lebanese government backtracked. On Monday, May 9, two Vatican sources told Reuters that the trip would be postponed, followed by an announcement from Lebanese tourism minister Walid Nassar that Francis’ visit to Lebanon in June would, in fact, not take place in June due to the Pope’s health issues.

Francis has been suffering from back pain (sciatica) and has been told by his doctors to rest. In recent weeks, in his public appearances he is in a wheelchair.

A visit from Pope Francis in June would have come at a delicate time for Lebanon, right after national elections in the country, which were held on May 15. The elections, which saw gains for political parties opposed to Hezbollah as well as the accession to Parliament of 11 candidates from newly-formed “independent” political parties, have been widely seen as a step forward for Lebanon.

In the face of massive economic and social collapse, however, as well as sectarian division (Hezbollah, for example, operates in large part as a “state within a state” in southern Lebanon, with a paramilitary wing that is far larger than the Lebanese Army), it is still unclear what kinds of concrete effects these electoral shifts will have. Many now speak of the “new poor” in Beirut — families who have lost everything in the economic collapse of the past several years, many of whom now seek a way out of the country at all costs.

Lebanon’s economic and humanitarian crises over the last several years have greatly affected religious orders in the country as well. There are 14 religious orders within the Maronite Church (5 male orders and 9 female orders) currently active in Lebanon, with a total of 719 monks and 812 nuns.

Now these orders — many of which are involved in running key institutions such as schools and hospitals — are struggling to continue their work. Due to the collapse of the economy and the devaluing of the Lebanese pound, many families in Lebanon have lost everything and can no longer afford to send their children to school.

Pope Benedict XVI meets with religious authorities in Beirut during his visit in September 2012 (photo: L’Osservatore Romano/AP).

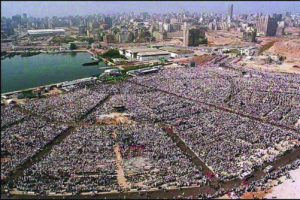

Hundreds of thousands gather at an open-air Mass celebrated by Pope John Paul II in Beirut during his trip to Lebanon in May 1997 (photo: Al-Safir/AFP/Getty Images)

Nevertheless, in the words of Bishop Michel Aoun of the (Maronite Catholic) Eparchy of Jbeil-Byblos (who, incidentally, shares a first and last name with the President of Lebanon), the Pope’s eventual visit “will give hope to the Lebanese people.”

Bishop Aoun also gave credit to Vatican officials for work that has already been done to support Lebanon: “Vatican diplomacy is doing its job in this field, in particular in urging countries to lend a hand to Lebanon at all levels.” (Archbishop Paul Gallagher, the Vatican’s Secretary for Relations with States, visited Lebanon in February of this year.)

According to Bishop Aoun, the papal trip to Lebanon was to include “a Mass in Beirut, a meeting with President Aoun and political officials in the Republican Palace, a meeting with the spiritual authorities and leaders of religious denominations, a meeting with young people and a Prayer in the Port [of Beirut].”

The Port of Beirut is, of course, the site of the horrific explosion of August 4, 2020, which left hundreds dead and many thousands more injured, and destroyed a part of the city that, to this day, has not been fully rebuilt.

A Story of Three Popes

As the leader of a Church with 1.3 billion members worldwide, Pope Francis has a unique ability among world leaders to focus attention on specific issues. At the same time, his multiple roles — as spiritual leader and apostolic successor to St. Peter, bishop of Rome, and head of state of the Vatican — mean that he has many different priorities at any given time.

For this reason, his commitment to visiting Lebanon means that he, and the Vatican, view the situation in the country as being of profound importance — as something worthy of international attention even in the midst of many other extremely pressing issues.

Why is the situation in Lebanon — home to a mere 6 million people, located at the far eastern edge of the Mediterranean, a country with no significant natural resources that is often overshadowed by its larger neighbors — so important that Francis has decided to make a personal visit?

To understand the answer to this question, we must return to the words of three Popes: Francis and his two immediate predecessors, Benedict XVI and John Paul II.

1997: John Paul II — “A New Hope for Lebanon”

During his pontificate, Pope John Paul II’s great interest in Lebanon was well-known. His words about Lebanon in a 1989 letter to the Lebanese Catholic bishops remain a popular refrain for Lebanese of all faiths to this day: “Lebanon is more than a country… it is a message of freedom and an example of pluralism for the East as for the West.”

John Paul’s 1997 Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation, A New Hope for Lebanon, was the result of many years of dialogue between the Vatican, representatives of the Catholic Church in Lebanon, and John Paul himself. John Paul was able to travel to Lebanon in May of 1997 for the official signing of the Apostolic Exhortation.

The Apostolic Exhortation begins with a moving reflection on Lebanon’s unique place within the Christian world, and the unique challenges that arise from the presence of many different faiths in one country:

“Lebanon is home to Catholics who are members of different patriarchal Churches, as well as of the Latin Apostolic Vicariate,” John Paul wrote. “Because of this fact, right from the time he begins to reason, the young baptized Lebanese Catholic recognizes himself as a Maronite, or Greek-Melkite, or Armenian Catholic, or Syriac Catholic, or Chaldean, or Latin. It is therefore through this path that he opens himself to the Christian life and that he is called to discover the universality of the Church.

“Christians from other Churches and Ecclesial Communities also live in Lebanon. The other important part of the population is made up of Muslims and Druze. For the country, these different communities constitute at the same time a wealth, an originality and a difficulty. But bringing Lebanon to life is a common task of all its inhabitants.”

Later on, there is an assessment of the difficulties Lebanon faces. These words, written between 1995 and 1997, would not seem out of place today, in 2022:

“This project is largely conditioned by the years spent in war and by the serious situation that hangs over this region of the Middle East. I am aware of the current major difficulties: the threatening occupation of southern Lebanon, the country’s economic situation, the presence of nonLebanese armed forces on the territory, the fact that the refugee problem has not yet been fully resolved, as well as the danger of extremism and the impression of some that they are frustrated in their rights. […] From this, the temptation to leave insinuates itself more and more among the Lebanese, especially among the young.

“But despite everything, hope remains alive in them. They have not lost their faith in themselves, nor their attachment to their country and its democratic tradition.”

John Paul’s visit to Lebanon was, in some ways, a culmination of several decades of intense efforts to prevent the country from splintering. In his book Dévastation et Rédemption, Fady Noun, a Lebanese journalist, offers a little-known account of how the Polish pontiff’s dedication to Lebanon originated.

“When in October 1978, after his election, [John Paul II] went out to greet the crowds in Saint Peter’s Square, at a time when posters and banners were not allowed, he saw one being raised that said, ‘Holy Father, Save Lebanon!’ just before it quickly disappeared,” Fady wrote. “Like an arrow, that message struck his heart. At the end of the celebrations, after greeting everyone, he came back inside and went to kneel before the Almighty. He asked Jesus, present in the Eucharist, to let him live long enough to save Lebanon.”

Such a simple deed can influence the course of events. In 1978, John Paul II had already decided that Vatican diplomacy would focus on preventing Lebanon from breaking up.

John Paul II saw in Lebanon many commonalities with his home country of Poland, and he believed sustained dialogue and diplomacy could achieve a breakthrough for Lebanon, similar to the cascade of events that had followed his 1979 visit to Poland.

But despite the pontiff’s vision for Lebanon, progress there was not destined to take the form of sweeping, dramatic changes like glasnost, perestroika, or the Fall of the Berlin Wall, but rather slow, incremental advances like the signing of the 1989 Taif Agreement and the disarmament of various militias.

The 2005 Cedar Revolution and the peaceful withdrawal of Syrian troops from Lebanon — a year after John Paul’s death — seemed to validate the Vatican’s “long game” diplomatic approach. However, enormous sectarian tensions remained, especially around the question of Hezbollah. Then the 2011 “Arab Spring” upended the Middle East and brought a fresh wave of challenges to Lebanon.

Jocelyne Khoueiry: From Bullets to Bibles

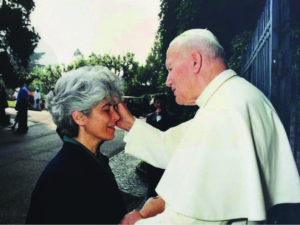

In one of the most iconic images from his 1997 visit to Lebanon, Pope John Paul II is sharing a quiet moment with a woman on a tree-lined street (photo right).

In one of the most iconic images from his 1997 visit to Lebanon, Pope John Paul II is sharing a quiet moment with a woman on a tree-lined street (photo right).

The woman seems to be overcome by emotion; her face tells a story of great suffering, but also of having at last found peace and joy. Her name was Jocelyne Khoueiry, and she was born in 1955, in Beirut. Her family was Maronite Catholic, but the strongest influence in their life was the Kataeb Party, also known as the Phalanges, a Christian political party with a paramilitary arm, which had its office across the street from their house.

Jocelyne and her brothers joined the Phalange militia in the early 1970s, just before the outbreak of Lebanon’s civil war in 1975. But her life would soon change after she experienced a vision of the Virgin Mary on May 7, 1976 while on a routine patrol on the roof of the Regent Hotel in Beirut. A few minutes later, Jocelyne was involved in a major battle with a Palestinian militia group, which ended when she threw a hand grenade from the roof of the hotel, killing the Palestinian commander.

For her courage, Khoueiry became famous as a symbol of the “Christian resistance” in Lebanon. But, as the years passed, she began to wonder if her Christian faith was truly compatible with the violence she and those who fought alongside her were engaged in. During a period of truce, from 1977-79, she attempted to join several religious orders as a nun. “I wanted to belong to God, and to belong to Him totally,” she recalled during a 2012 interview. She was turned down by the convents, who said her place was in the world.

Khoueiry rejoined the Lebanese Forces in 1980, dedicating herself to sharing her faith with the women under her command. Jocelyne eventually commanded 1,500 women during the war, training them during the day and leading Bible studies at night. She also organized a team of 30 priests and 12 female spiritual guides to travel with the fighters. Khoueiry’s remarkable journey culminated with her renouncing violence and entering a two-year-long spiritual retreat, from which she emerged with a commitment to fight for Lebanon through living her Christian faith.

2012: Pope Benedict — “Maintain Peace” Between Christians and Muslims

John Paul’s predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI, arrived in Lebanon in 2012 at a time when the entire region of the Middle East stood once again at the brink of violence.

In neighboring Syria, a civil war had begun in 2011 — a war that would plunge the country into more than a decade of bloodshed, and result in more than 1.5 million Syrians — many of them Syrian Christians — fleeing into Lebanon as refugees.

On arriving in Lebanon, Benedict acknowledged the shadow of the war, saying, “I have come to Lebanon as a pilgrim of peace, as a friend of God and as a friend of men.”

He also offered Lebanon as an example for Syria and other countries in the region where sectarian violence was erupting: “The successful way the Lebanese all live together surely demonstrates to the whole Middle East and to the rest of the world that within a nation there can exist cooperation between the various churches and at the same time coexistence and respectful dialogue between Christians and their brethren of other religions.”

While the years following the end of the Lebanese civil war in 1990 had been punctuated by wars between Israel and Hezbollah and political struggles and assassinations within Lebanon, the Arab Spring was seen as an even more pivotal moment, one in which tensions between Christians, Muslims, and other sectarian communities such as Alawites and Druze had the potential to boil over into a wider war, and ultimately even threaten the continued survival of Christians in the Middle East.

Benedict, like many others in the Vatican, was observing the situation in Syria deteriorate into chaos, and likely saw the disastrous consequences for the Christian community that this chaos would bring — including the genocide of Christians in Iraq that would come about several years later after the rise of ISIS in Syria.

In this sense, his visit to Lebanon was an attempt to reinforce the country, allowing it to stand as a kind of “stronghold” that would remain stable and at peace, no matter how much the rest of the region spun out of control.

Like John Paul before him, Benedict released an Apostolic Exhortation on the occasion of his visit to Lebanon: Ecclesia in Medio Oriente (The Church in the Middle East).

Lebanese crowds greeting Pope Benedict upon his arrival in Beirut in September 2012 (photo: Hasan Shaaban/Reuters).

In it, he spoke of the impact of “two new realities”: the “opposing trends” of “secularization, with its occasionally extreme consequences,” and “a violent fundamentalism claiming to be based on religion.” Both of these trends, Benedict believed, ran counter to (and could be countered by) what he termed “religious freedom” and “healthy secularity”:

“There is a need to move beyond tolerance to religious freedom,” Benedict wrote. “Taking this step does not open the door to relativism, as some would maintain. It does not compromise belief, but rather calls for a reconsideration of the relationship between man, religion and God. It is not an attack on the ‘foundational truths’ of belief, since, despite human and religious divergences, a ray of truth shines on all men and women…

“A healthy secularity… frees religion from the encumbrance of politics, and allows politics to be enriched by the contribution of religion, while maintaining the necessary distance, clear distinction and indispensable collaboration between the two spheres.”

2022: Francis — “In My Prayer the Desire for Peace”

Pope Francis greets Lebanese Cardinal Bechara Boutros Raï during a private audience at the Vatican on February 7, 2020 (Vatican Media)

Since becoming Pope in 2013, Francis has sought a solution to the ongoing and increasing flight of Christians from their communities in the Middle East.

Francis emphasized this commitment to dialogue during a Mass in Cyprus on December 2, 2021, at which many Christians from Lebanon were present (Cyprus, just a 50minute flight from Beirut, has a large Lebanese diaspora community).

“I look at you and see the richness of your diversity,” Francis said. “It is true, a beautiful ‘fruit salad’ [Italian: ‘una bella macedonia’]. All different. […] I carry in my prayer the desire for peace that rises from the heart of that country.”

Many have speculated that Francis originally sought to tie his visit to Lebanon into a larger itinerary that might also include a meeting in Jerusalem with Patriarch Kirill of Moscow. In recent days, however, it has become clear that no meeting between Francis and Kirill is on the imminent horizon, with the Pope himself saying that such a meeting “could lead to much confusion.”

It is likely that Francis has realized the backlash that such a meeting would cause within the 5.5 million-member Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, as well as with Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople, who has denounced the ongoing war in Ukraine as an “atrocious invasion” and called for solidarity with Ukrainians.

Whatever the reason behind it, the scrapping of a proposed meeting with Kirill means that the ambitions for Francis’ trip are now more limited. In a certain sense, Francis is following a similar path as his predecessors with respect to Lebanon.

Just as John Paul and Benedict before him, Francis can see the hope that Lebanon symbolizes — a hope for peace, acceptance, and the possibility for people of different faiths to live side by side. Just as they did, he has sought to draw attention to this model with a larger goal in mind.

For John Paul, this larger goal was peace between the Arab world, Israel and Christianity, especially in the Middle East.

For Benedict, it was the ending of the disastrous conflicts in Syria and Iraq and the preservation of Christian communities throughout the Middle East.

For Francis, it seems to be a resolution to the conflict in Ukraine, which has become a wedge deepening the conflict between Catholicism and Orthodoxy.

In the case of all three Popes, the larger goal has proved to be difficult to achieve.

Rather than using Lebanon as a path towards peace-making in a broader conflict, John Paul and Benedict both shifted their course, in the end seeking simply to protect and preserve Lebanon, so that the broader conflicts that surrounded it would not themselves change Lebanon beyond all recognition.

The approach that Francis will ultimately take with respect to Lebanon remains to be seen.

Facing Food Shortages and a Political Crisis

Many people who have been following the unfolding situation in Lebanon have recently begun to warn about looming food shortages. One source I spoke to, who had been present at the Lebanese Global Conference held on April 26, 2022, in Washington, D.C., went as far as to tell me, “‘Famine’ became the keyword over the course of the session.”

The conference featured talks from experts, analysts, and prominent figures like Samy Gamael, the current leader of the Kataeb Party in Lebanon, as well as American Congressmen Darrell Issa and Darin LaHood, who are both of Lebanese descent.

The conference’s most urgent discussions centered on how Lebanon will be affected by the war in Ukraine. The production of staple foods in Ukraine such as wheat — staples on which much of the Middle East depends — is expected to be greatly diminished this year.

Some estimates place the number of people who will be affected by food shortages as a result of the war as high as 500,000,000. “One full year of crisis in Ukraine will equal four years in the countries that depend on it,” the source told me.

The individual I spoke with also echoed what many Lebanese have told me over the past several months: that without active leadership on the part of the Vatican, the United States and Europe, Lebanon will go the way of other failed states in the region such as Syria, likely descending into chaos and war.

“There are 100,000 combatants [in the Hezbollah paramilitary forces] vs. 7,000 [in the Lebanese Army],” the source told me. “Nobody can compete with this power.

“We need peace. We need political stability in Lebanon.”

When I asked about the Christian political leadership in Lebanon, many Lebanese with whom I spoke offered harsh criticism.

“We don’t have true Christian leaders,” one Lebanese Christian told me. “Only Patriarch Raï.”

“The problem is that even Christians are divided,” another told me. “The Shia [Muslims], when it comes to politics, are united. Christians are united with them [i.e., some Christian political parties ally with Hezbollah] because they are after power, they are after their own interests.”

For now, Lebanon will continue waiting — waiting for the visit of Pope Francis, waiting to see if the glimmer of hope offered by its election proves to be a mirage, waiting, in short, for a miracle.

“We’re stuck,” a friend in Lebanon told me. “We need prayers. I believe in miracles because I am a Christian… We need intervention of the United States more boldly in Lebanon. We need an agreement with Iran, to keep Lebanon impartial from all of the struggles around it. Right away, Hezbollah would vanish.”

John Paul II’s words about the Lebanese people ring true even today, even as the crisis deepens: “Despite everything, hope remains alive in them.”

Fr. Hani Tawk, a Maronite priest who established an organization to feed the “new poor” in Beirut following the August 2020 explosion, affirms this, bringing a message of light in a time of darkness. “We are passing through a very miserable situation,” he said in a recent interview with Catholic News Service. “But we believe there is light at the end of this tunnel. We believe in the Resurrection.”

Christopher Hart-Moynihan is the Director of Friend of Lebanon, a Unitas project of Urbi et Orbi Communications.

Facebook Comments