A review of Julia Meloni’s new book The St. Gallen Mafia: Exposing the Secret Reformist Group Within the Church

By Dr. Darrick Taylor

“Their inward thought is, that their houses shall continue forever, and their dwelling places to all generations; they call their lands after their own names. Nevertheless man being in honor abideth not: he is like the beasts that perish.” –Psalm 49:11-12

Julia Meloni, author of THE ST. GALLEN MAFIA: EXPOSING THE SECRET REFORMIST GROUP WITHIN THE CHURCH, Tan Books, 2021

Men love futility. They must, if the annals of tedious Vatican politics are any indication. Julia Meloni’s The St. Gallen Mafia: Exposing the Secret Reformist Group Within the Church (Tan Books, 2021), amply demonstrates this thesis. For the uninitiated, the title refers to a group of cardinals — Gottfried Daneels of Belgium, Walter Kasper of Germany, Carlo Maria Martini and Achille Silvestrini of Italy, and Cormac Murphy-O’Connor of Britain — who for years tried to secure the election of a Pope who would forward their designs to “update” the Church. These cardinals met at the former monastery of Sankt Gallen in Switzerland in the latter years of John Paul II’s pontificate, to oppose the “conservative” drift under his CDF chief, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. In Pope Francis, they appear to have their man. When giving a talk on the publication of his biography in 2013, Daneels spoke of their group as a “mafia,” and the name stuck. Some even took credit for Francis’ election, though they quickly walked this back, not wishing to reveal the nature of their group.

Those who have followed the papacy of Francis closely will find much that is familiar in the book, especially in the second half entitled “Time.” These chapters detail the main events of Francis’ pontificate: the reappearance of a disgraced Cardinal Daneels (for covering up sexual abuse) on the balcony the day Francis was elected, the role of Walter Kasper in the Synod on the Family in 2014, the furor over Amoris Laetitia that followed it in 2015 (and since), the Synod on Youth of 2018, and the Amazonian Synod in 2019, which saw attempts to end mandatory clerical celibacy. Meloni makes clear the links between these synods and attempts to alter the Church’s faith, for anyone who is not familiar with these events.

Moreover, she connects the event of Francis’ papacy to the activities of these cardinals prior to his election, in the first part entitled “War.”

She details how the group used discussions of “decentralization” and “collegiality” as a coded way of articulating liberal theological demands. Most especially, she establishes the ties between Martini and Francis with great clarity. In her telling, not only the ideas but also the words of Francis match almost exactly those of Martini, using interviews and speeches of both men to great effect. Another takeaway from this part of the book is how much opposition to Ratzinger galvanized this group, and how personal it was to them. One gets the sense that men like Kasper, who feuded with Ratzinger for decades, wanted to triumph over Ratzinger, who as head of the CDF so often shot him down.

Meloni documents these ideological and personal conflicts using sources in several languages, and includes details I was not aware of. For example, though he later denied it, she unearthed a blog post by Austen Ivereigh, claiming the group had sought Bergoglio’s permission to push him as a candidate in the 2013 conclave. I did not know of the rumor that some bishops appealed to Ratzinger during the Synod on the Family to intervene, nor that Silvestrini was close to John Paul II.

I had also forgotten that Francis had quashed an investigation of Murphy-O’Connor for covering up sexual abuse shortly after becoming Pope.

Meloni’s book provides a readable narrative of the triumph of the most powerful faction in the Church today. For this alone, she is to be commended.

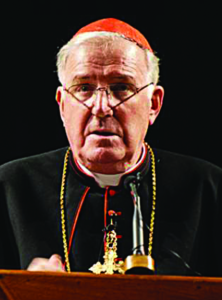

Gottfried Daneels of Belgium

I do have a few criticisms. The book’s subtitle notwithstanding, there is nothing terribly secret about “the mafia.” All her sources are publicly available, many on the internet, even though members of the group are careful not to broach their intentions too loudly and then only to friendly audiences. As her book amply demonstrates, they have been pushing liberal theological ideas since the 1960s. Even then, the “new answers” Cardinal Martini wanted the Church to give on sexual questions aren’t even that new: what the “mafia” wants the Church to be, from what I can tell, is a sort of Christian philanthropic organization espousing a pagan sexual morality, not unlike what the Emperor Julian (331-363) attempted in the late Roman Empire. In their modern guise, their ideas descend from liberal Protestant and Catholic modernist theologies that are more than a century old.

Walter Kasper of Germany

Moreover, despite the book’s sometimes ominous tone, it demonstrates that this group can be opposed successfully: the refusal to adopt the Kasper proposal at the 2014 Synod, and the publication of Benedict’s book on celibacy, which thwarted the Amazonian Synod, are two examples. But it takes bishops and Church leaders willing to do this. The success of the group depends on manipulating ordinary Catholics’ sense of obedience and loyalty, which they know are stronger than any attachment to orthodoxy. This is why supporters of Francis spend so much time accusing his critics of disloyalty; loyalty to the Pope and to the institutional Church are practically the only thing most Catholics clearly understand about their faith, and the only things, in practice, all share in common. It is psychologically very difficult for a faithful Catholic to criticize the Pope, and having one like Francis provides cover for the progressives seeking the cooperation of the laity in changing the Church.

Pope Benedict XVI with Italian Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini

Achille Silvestrini of Italy

I say this because, after reading Meloni’s book, one might come away with the impression that this group and its acolytes comprise some sort of omnicompetent organization, like villains in a James Bond film. I doubt this very much. None of them, save for Kasper, are possessed of any great intellect, and their attempts to manipulate the perceptions of the faithful are sometimes comically inept. (I am thinking of the press rollout for the publication of Francis’ collected works, which included a fabricated quotation by Ratzinger.) It is true they have attempted for many years to alter the Church’s official beliefs, and the “mafia” has been quite successful at seizing and controlling institutions. But taking advantage of the charity and goodwill of the ordinary faithful, not to mention two Popes, is no evidence of competence or strength. Their rhetoric about “patience” and playing the long game belies the precariousness of their position. Their most animated supporters are frustrated by what they see as their lack of progress. They know their work can be undone in the future; the experience of two “conservative” Popes following Vatican II has taught them as much.

Cormac Murphy-O’Connor of Great Britain

Faithful Catholics are in a terrible state, having to balance loyalty to the papacy with maintaining the immutable elements of the faith that these cardinals want to alter. In that regard, The St. Gallen Mafia provides some hope. They have no doubt caused much damage and may do so for some time. But Meloni’s book demonstrates the essentially political character of the St. Gallen Mafia: its main concern is with gaining merely human, institutional power over its perceived opponents.

They apparently believe that by manipulating public opinion in and outside the Church, by seizing the Church’s bureaucracy and putting their erroneous ideas into Church documents, their achievements will be “irreversible.” Despite appearances, such efforts are doomed to failure.

Human power can defeat one’s enemies, but it can never guarantee the permanent success of one’s designs; in human history, no one ever “wins” in that sense. The machinations of the St. Gallen Group and its supporters have nothing to do with the power of God, which alone can establish the Church in perpetuity. Human power may destroy much that is good, but it cannot erase what is eternal. In the end, only God wins, and the only question is whether we will be on His side, or not.

Dr. Darrick Taylor is an adjunct professor of history at Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas. An adult convert to Catholicism, he earned his PhD at the University of Kansas, and produces a podcast called Controversies in Church History.

Dr. Darrick Taylor is an adjunct professor of history at Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas. An adult convert to Catholicism, he earned his PhD at the University of Kansas, and produces a podcast called Controversies in Church History.

Facebook Comments