Cardinal Dominik Jaroslav Duka, OP, 69, was born in 1943 in Hradec Králové, Bohemia (now Czech Republic). Today he is the 36th archbishop of Prague. He was ordained on June 22, 1970, at the age of 27. In 1972, he made his solemn profession in the Dominican Order. In 1975, the Communist regime deprived him of authorization to carry out the sacred ministry. For almost 15 years, until the regime collapsed in 1989, Duka worked as a designer at the factories of Škoda at Plzeň, while working secretly in the Order as a novice master and teacher of theology. After the fall of Communism, Duka was made a bishop (in 1998) and on February 13, 2010, Pope Benedict XVI appointed him archbishop of Prague. On his appointment, Duka said: “The Church must engage in a dialogue with society and must seek reconciliation with it. Twenty years ago, we were euphoric about freedom; today we live in an economic and financial crisis, and also to a certain extent in a crisis of values. So the tasks are going to be a little more difficult. But thanks to everything that’s been done, it will not be a journey into the unknown.” One of Duka’s chief concerns has been the long-standing issue of the restitution of Church properties, which were confiscated by the Communist regime. After previous attempts at an agreement had failed — most notably in 2008 under Cardinal Vlk — the Czech government in mid-January 2012 agreed to a compensation plan, under which the country’s 17 denominations, including Catholic and Protestant, would get 56% of their former property now held by the state — estimated at 75 billion koruna ($3.7 billion) — and 59 billion koruna ($2.9 billion) in financial compensation paid to them over the next 30 years.

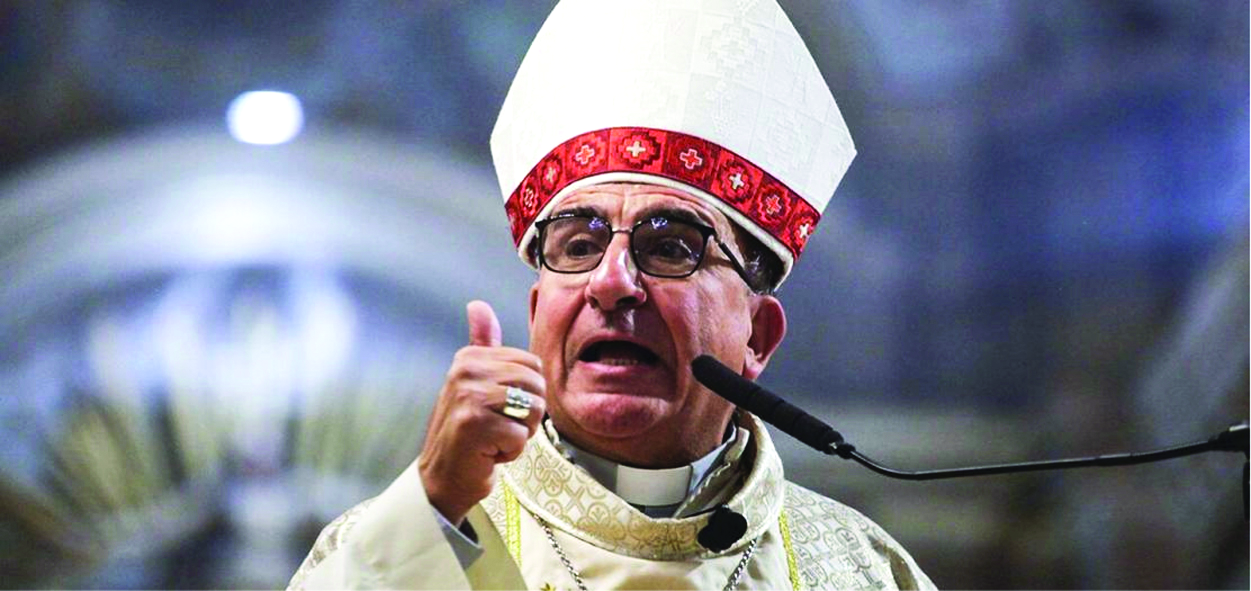

His Eminence Dominik Cardinal Duka of the Czech Republic.

The patron saints of Hradec Králové in Bohemia, where you were born in 1943 and appointed archbishop in 1998, are St. Clement and St. Joseph Nepomuk, who is buried in Prague’s cathedral. Are they your favorite saints? If not, who is?

Dominik Cardinal Duka: As a Dominican, my favorite saint is St. Dominic. As a native of Hradec Králové, I can’t forget St. Adalbert and St. Clement of Ohrid, who is the patron of the diocese of Hradec Králové, where I was bishop before I left for Prague in 2010, when the Holy Father appointed me archbishop here. And here in Prague, it is St. Wenceslaus, St. Agnes of Bohemia and Zdislava Berka. I’d also like to add St. Thomas Becket.

When did you first sense your vocation?

Duka: The world of my childhood was a world of soldiers, travelers and priests. Priests entered my life thanks to the stories told me by my father’s colleagues, who were military aviators like my father. They all recounted the lives of priests deeply respected for their courage. These priests’ religious faith distinguished them from the common man. When I was 14 years old I heard a sermon about a priest who had disavowed his vocation. Suddenly I felt the desire to become a priest, someone who isn’t afraid to tell the truth and who, according to my catechist, draws inner strength from the unique example of the Lord Jesus.

Why did you choose the Dominican Order?

Duka: My special loves were always the Jesuits and the Dominicans. My love for the Dominicans was because of their literature, which I was reading even then, and because of my love for the liturgy. The Jesuits put less emphasis on liturgy. On January 6, 1969, I made my temporary profession in the Dominican Order; on June 22, 1970, was ordained a priest; and on January 7, 1972, made my solemn profession in the Dominican Order.

The Archbishop’s Palace in Prague (Lucy Gordan photo)

Could you please describe the moment in 1975 when the Communist government deprived you of the authorization for the sacred ministry? What reasons were you given?

Duka: The unpleasant pressure of “normalization” after the Warsaw Pact invasion of my country in August 1968 wasn’t very intensive in parishes along the border, where I was active. Nonetheless, the police often interrogated me. The first times I was moved to different locations, which was the strategy of the Communist regime against too free priests, but one day, when I came back from vacation, I found a notice on my table saying that, because of my untrustworthiness, I’d lost my state permission to work as a priest.

Can you also describe the moment when you were jailed in 1981? What were the charges?

Duka: When I was deprived of my “state approval,” I got a job as a designer in the SKODA factory in Pilsen. In spite of this new “career,” I continued working for the Dominican Order. My duty was to train novices and teach theology. During a vacation from SKODA, I brought home some samizdat (illegal publications made by hand and passed from reader to reader), and I started to study this material. At this moment, seven guys with a search warrant entered my house.

On June 29, 2010 in St. Peter’s Basilica, Archbishop Duka received his pallium from Pope Benedict XVI (Galazka photo)

Do you have a special memory of Pope John Paul II?

Duka: I have many memories of him, especially our first hurried meeting in Cracow in the Dominican Trinity Church in the 1960s; then when he was still an auxiliary bishop, at the funeral of our Cardinal Trochta in 1974; and years later, during my first visit to Rome in 1990.

How often do you come to Rome now?

Duka: Three or four times a year.

You have been often to the United States?

Duka: I’ve been to the US three times. The first time was still during the Communist era; I took part in the general chapter of our Order in Oakland. My second visit was at the beginning of the new millennium at the University of St. Thomas Aquinas for the ecumenical conference on faith in the life and culture of the Czech nation and of Central Europe. My most recent visit to the US was in September 2011 when I took part in the Mutual Inspirations Festival- Antonín Dvorák. I met many interesting people — representatives of the American Bishops’ Conference and many Czech-Americans. I had also the chance to talk to George Weigel, an American political and social author, especially well-known for his biography of John Paul II.

How will history judge Pope Benedict XVI and his papacy?

Duka: It will be history that will indeed judge him, but I think he will always be respected as a Pope with an immense intellectual purview, someone able to lead a dialog with the world of agnosticism. Also, his effort to establish ecumenical relations with Eastern Churches, in the first instance with the Orthodox Church, is very significant, as is his attempt to legalize the Church in China.

The Roman Church of Saints Marcellinus and Peter.

On April 21, 2012, you were appointed to the Congregation for the Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life. What does the Congregation do?

Duka: This Congregation is one of the main Vatican offices. Its task is the acceptance, supervision and juridical administration of the Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life.

You were also appointed to the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace; what are your duties there?

Duka: The Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace helps the Pope to support justice and peace in accordance with Catholic social teaching. As a member of this Council, I study social, ecological and other problems of today’s society, not only in my country, but also abroad.

On February 18, 2012, you were elevated to cardinal and appointed the cardinal-priest of Saints Marcellinus and Peter; is that your favorite church in Rome?

Duka: I was glad to receive this church. It was the cardinal church of Pope Pius XI, who was enamored of the Czech Republic. This church was also connected with Cardinal Lustiger. He helped the Church in my country during Communism. I had many opportunities to talk to him.

What is your favorite church in Prague and in the Czech Republic?

Duka: As with every Czech, it’s the Cathedral of St. Vitus. As a native of Hradec Králové, I love its Cathedral of the Holy Spirit, and then of course all the pilgrimage destinations dedicated to the Virgin Mary: the Marian shrines of Svatá Hora, Stará Boleslav and Velehrad.

I read that the Czech Churches, both Catholic and Protestant, will receive only 56% at best of their former property now held by the state. Isn’t that too small a percentage? Is it a starting point or is it better than nothing?

Duka: The situation is quite complicated. We’re trying to rectify a Communist injustice and at the same time to finance our churches in the future. The law says that churches have to obtain 56% of their historical patrimony, which was confiscated by the Communists between 25 February 1948 and 1 January 1990. The rest of the historical church property should be compensated with 59 billion Czech crowns paid over the next 30 years. Financial compensation was chosen because now these Church possessions belong to private persons or towns and municipalities.

What is the present official relationship between the Czech Republic and the Holy See?

Duka: The covenant between the Czech Republic and the Holy See was signed in 2002 by our minister of foreign affairs, Cyril Svoboda, and the apostolic nuncio, at that time Archbishop Erwin Ender, but it wasn’t ratified by Parliament. At this time its actualization is in progress. Many think that the negotiations will finish after the rectification of property between the Church and State.

Is the “new evangelization” the greatest challenge facing the Church today?

Duka: Yes, it is! It is necessary to open the Church, which is often withdrawn and which too often lives a consumer-oriented spiritual life. The Church has to open up to all of society and has to make strong efforts to achieve its mission.

Facebook Comments