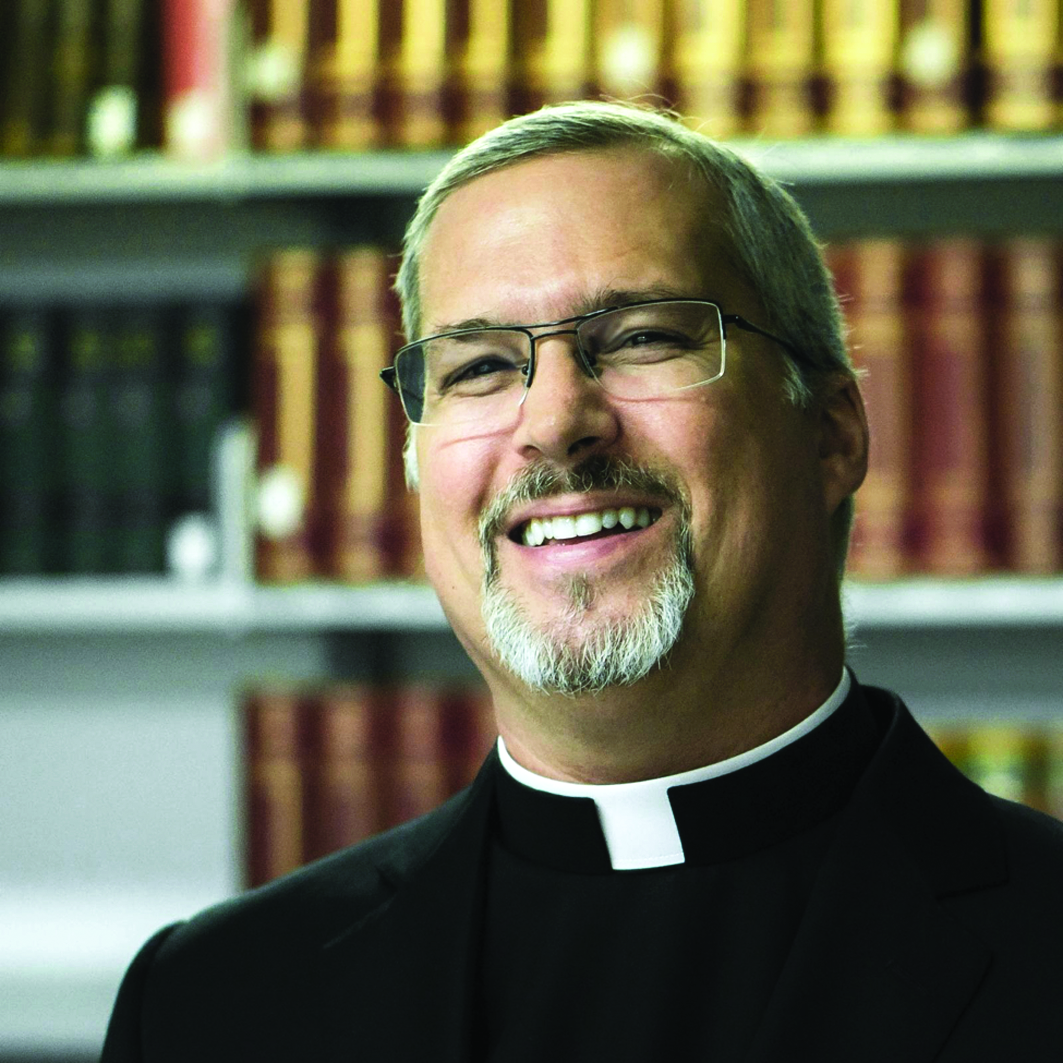

As Pope Francis passed the end of the first year of his pontificate on March 13, at least six books and four television series and films about him appeared. What has changed with the arrival of this “Pope from afar”? And in what areas has he made the greatest impact? Lucio Brunelli, the Italian state television (RAI) Vatican correspondent for two decades and a key religion reporter for even longer — recently chosen chief editor of the television network of the Italian bishops’ conference, TV 2000 — chooses his words carefully. For him, this is a “special” Pope, and he doesn’t try to hide it…

“During preparations for the Conclave, Bergoglio’s talk left all the cardinals speechless, both for its expressed content… and for its profoundly religious spirit, a plausible spirit that lit up his words”

On the eve of the 2013 Conclave, you were one of the few journalists who indicated Bergoglio as a possible papal candidate. Why? Only for affection towards a cardinal you knew so well?

Lucio Brunelli: I did have a certain affection for him, as I still do now, without a doubt. But my conviction that the cardinal from Buenos Aires was a possible candidate was based on fact. I perceived a great desire for change among the cardinals (especially the non-Europeans) after the scandal of “Vatileaks” and the dramatic renunciation of Benedict XVI. The bark of Peter seemed beached, with dark waves surrounding it. They were looking for a man of God, with a great spiritual strength, one not from the Curia, and not from Italy, because the Italians, whether rightly or wrongly, were considered largely to blame for the pitiful situation of the Roman Curia. Bergoglio fit the description as no one else did. The only doubt concerned his supposed unavailability, due to a rumor that had swept through the 2005 Conclave that he had refused the votes of those who had sought in him a “pastoral” alternative to the “doctrinal” candidate, Ratzinger.

Plus there was his age to consider; he was 76 years old.

These doubts were all swept away during preparations for the Conclave, in the General Congregations, held behind closed doors. Bergoglio’s talk left all the cardinals speechless, both for its expressed content (a Church that must emerge from within itself, free itself from the spiritually mundane, to allow Christ’s light to shine brighter among the people of our time, to the furthest existential outskirts…) and for its profoundly religious spirit, a plausible spirit that lit up his words.

When I received reliable news about the warm reception his speech had received, I called my editor-in-chief to propose a piece on Bergoglio, to be added to the “short-list” of pieces on possible papal candidates we had begun airing, one every evening.

“Are you sure he won’t be 65th on the list?” the RAI news people asked me.

“I’m sure,” I answered. “He’ll be much, much higher up.”

My piece aired that same evening, March 9. I remember, too, an emblematic line from an influential man of the Church, the evening before the Conclave: “He may be elderly, but all we need is four years of a Bergoglio papacy to reform the Church.” In short, I harbored no more doubts that the Argentinian cardinal was a strong candidate, and I read the headlines of Corriere della Sera and La Repubblica with a sense of irony: until the very end, they presented the Conclave as a two-man race, a toss-up between the Italian Angelo Scola and the Brazilian Odilo Scherer. Even so, the evening of March 13, while I was on live for my newscast, I admit that when I heard Cardinal Tauran pronounce Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s name in Latin as the new Pope, I nearly fainted with emotion and happiness.

“I am fascinated by what I see reflected in the faithful when I am reporting at St. Peter’s: wonder, deeply felt emotion, gratitude. It reminds me of the disciples, 2,000 years ago in Palestine, who participated with astonishment and strong emotion in Jesus’ preaching and actions”

We are not yet four years into Bergoglio’s papacy, but after the first year’s close, where do you think he has made his most profound mark?

Brunelli: Above all, he has influenced the way the Church is perceived among the people. And there is something miraculous in the speed of this transformation. All over the world, people are looking to the Pope and his preaching with wonder, interest, fondness. And a strong impression seems to have been made precisely on those who until now had been the furthest from the Church, and most diffident toward her.

Then, too, Francis has laid the basis for radical change in the Roman Curia, to free it from excessive bureaucratic centralism and the vice of ecclesiastical career-seeking. The first cardinals he named were a concrete sign in this direction. Up to now, certain Vatican offices or Church dioceses could lay claim to being headed by a cardinal, automatically, but that era is finished.

Another area where Francis has made a strong mark is in the composition of the Congregation of Bishops, one of the most influential dicasteries of the Curia, since that is where decisions are made on the leadership of the Catholic Church and the form it will take. Francis wants bishops who “live with the smell of the sheep”; he doesn’t want functionaries. He wants the bishops to be close to the people, able to preach, with their lives, the Gospel of that mercy which is Christ’s own.

Compared to Cardinal Bergoglio as you knew him before the election, what strikes you most about Pope Francis?

Brunelli: I am quite struck by his strength, the quiet determination, the joyous obstinacy with which he carries out his decisions, from his decision to live at Santa Marta, and his refusal to be managed by a court, to his actions that are shaking up the Italian Bishops’ Conference. I perceive him as stronger and more serene. He doesn’t allow himself to feel the stress of the enormous task of reforming the Church, or the weight of resistance. It is evident that he finds his rest in God, that he feels he is doing what God has called him to do, and thus he continues along his path, taking upon himself a great burden but never losing his serenity. Besides this, I am fascinated by what I see reflected in the faithful when I am reporting at St. Peter’s: wonder, deeply felt emotion, gratitude. It reminds me of the disciples 2,000 years ago in Palestine, who participated with astonishment and strong emotion in Jesus’ preaching and actions. Because true reform means returning to those origins. And this is not something that can be planned while sitting around a table, which is what Benedict XVI also taught: it is the grace that God grants in certain times and to certain people, to make it easier for everyone to seek the Good, the True, the Beautiful.

A certain resistance has been emerging, both close to the Pope and in other areas of the Church. Do you observe this? And what impact has it had?

Brunelli: There are different kinds of resistance, we can say: ideological, psychological, and resistance coming from authority and power. Part of the ecclesiastical establishment is taking the Pope to task over not having said enough against the moral evils that the Church hierarchy concentrated so much energy on and fought political battles over in past decades: abortion, euthanasia, gay marriage… Obviously, Pope Francis shares the same principles, and has defined as “horror” the tragedy of unborn babies, victims of abortion. But he wants to win souls, he is interested in salvation, meaning the happiness of souls — also, and above all, the souls of those who are furthest from the Church. And, being a man of God and a shepherd with long experience in the field, he knows that Christianity doesn’t enter hearts through the obsessive repetition a series of “no’s,” but by drawing people, attracting them. A certain “beauty” that “goes before us and inspires us to follow” as he said, speaking about the Three Wise Men, at the Epiphany Angelus.

I am strongly convinced that simply observing, with purity of heart, the tenderness that Pope Francis shows when he interacts with the elderly, disabled people, and children with grave illnesses or handicaps, is of educational value a thousand times more concrete and persuasive than scores of hard-line editorials against euthanasia and abortion. Only circles of the most narrow-minded Catholic militants, those practicing an ideological Christ-less “Christianity,” can remain unmoved and unhappy over what is happening.

And what about psychological resistance, and resistance coming from authority and power?

Brunelli: Sometimes ideology is merely a mask. There is a part of the clerical world — not the entire clerical world, luckily, but a part of it — that feels it has been laid bare, in its spiritual pettiness, by Francis’ preaching and witness. People with chips on their shoulders, as I was told by an honest associate of the last three Popes. It is the same anger that brewed in the Scribes and Pharisees when faced with Jesus’ meekness and truthfulness, a presence they were not able to imprison within their own framework. It is hard to quantify this resistance — how can you measure a person’s heart? — but it exists, and the Pope is well aware of it. Sometimes it has to do with economic interests outside the Vatican, and the fear of losing contacts.

“I am strongly convinced that simply observing, with purity of heart, the tenderness that Pope Francis shows when he interacts with the elderly, disabled people, and children with grave illnesses or handicaps, is of educational value a thousand times more concrete and persuasive than scores of hard-line editorials against euthanasia and abortion”

What is the secret of this Pope’s wide appeal, his ability to speak to everyone? Maybe the fact that he prefers gentle rebukes to a fire-and-brimstone approach?

Brunelli: Gentleness… I like that reference. There is a delicacy, a discretion, that is part of the very heart of the Christian experience, because faith is a gift of grace, and whoever receives it knows that one can’t simply demand it: No one can be forced into believing. Similarly, you can’t command a man to fall in love with a woman. But it happens, like the surprise of an encounter.

A Christian, a true Christian, has a true belief in freedom. “Please, sorry, and thanks,” the three words Pope Francis suggests to all as the secret to a good family life, are profoundly Christian. A believer adopts them spontaneously in his relationship with Jesus: sorry, thanks… We are conscious of our own shortcomings, and grateful for His pardon, which we don’t take for granted. This is something I am learning from Francis, in the wake of Benedict’s pontificate: the more the Church goes back to basics, meaning the mystery of mercy as the true heart of the Gospel, the more she speaks to every person, and the total person: to that person’s wounds and desires. And those desires, in their most profound sense, are universal: they unite people from the four corners of the earth, from the educated and well-off to the underprivileged fleeing hunger and poverty.

“He makes clear and sacrosanct observations: for example, that we make a big fuss over a small dip in the stock markets, but we have lost the capacity to cry over refugees who die at sea, and we merely shrug when homeless people or drug addicts die: these are unwanted scraps of humanity in a world where money rules over all…”

Gentleness comes into it, to be sure, but Francis has also been vehement in denouncing corruption in politics, and the inhumanity of an economy that kills…

Brunelli: In these situations, too, I am struck above all by the Pope’s free strength. He makes clear and sacrosanct observations: for example, that we make a big fuss over a small dip in the stock markets, but we have lost the capacity to cry over refugees who die at sea, and we merely shrug when homeless people or drug addicts die: these are unwanted scraps of humanity in a world where money rules over all.

But if these observations were only political statements, or a theatrical throwing up of hands in horror, they would not have the same effect. Even when he uses severe words, people understand that Francis has their welfare at heart; he knows that the value of people lies not in any power they might have, but in the fact that they exist, and that they were made by God. Thus, people accept his severity, it affects them and serves to educate them.

Regarding his passion for the poor, the “flesh of Christ,” there is no sign of Peronist populism or hidden Marxism there: Francis says that it is a matter of theology: an all-powerful God decided to become poor for love of mankind. Sharing where there is need, serving humanity in its most wounded form, is God’s own method.

Here is a Pope who believes in the efficiency, even “politically” speaking, of prayer. He said so recently, in his Easter message, reminding the faithful of his call to prayer and fasting for peace in Syria.

Brunelli: Last September, it seemed only a matter of hours before the American military would strike against Syria. The Pope maintained that such a situation would only make matters worse for the civilian population, already tormented by a fierce civil war. Millions around the world participated in the day of prayer and fasting, and these included Catholics and other believers, and even non-believers. It is quite probable that this simple but intense spiritual mobilization helped stop an attack that had seemed inevitable. But the Pope certainly doesn’t feel that he solved the Syrian crisis. There was never any hint of triumph in his words. Also because people are still dying there. Francis will keep on urging the international community to seek, with conviction, a political solution that will bring the war to an end. And at the same time, he will continue praying and asking us to pray for peace. He truly believes in the effectiveness of prayer, much more than we do.

Once he said that we shouldn’t be afraid of raising our voices, even to contend with God, to get Him to turn toward us and, finally, give His attention to our cries.

Facebook Comments