The Church’s social teachings suggest a “Just Third Way” — an economic system that respects the dignity of the person

By Michael D. Greaney

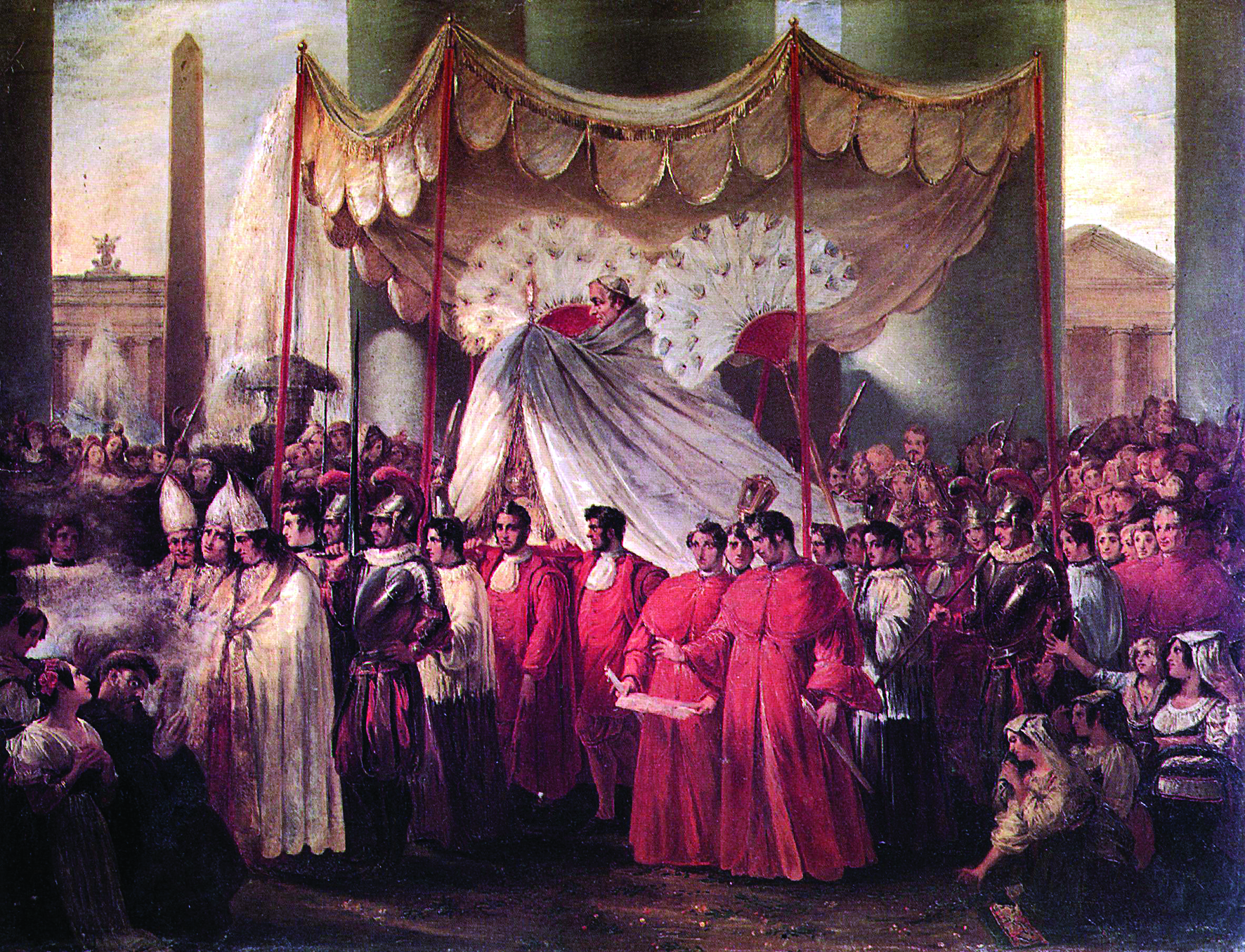

Pope Gregory XVI (1831-1846) during a Corpus Christi procession along the colonnade of St. Peter’s Square. Left, Félicité de Lamennais, considered by some as founder of liberal Catholicism.

Following the financial, industrial, and political revolutions of the eighteenth century, changes in the way people could be productive and participate in society called age-old ways of life into question. As the nineteenth century dawned, what would be called socialism and modernism gained a new foothold.

Following the financial, industrial, and political revolutions of the eighteenth century, changes in the way people could be productive and participate in society called age-old ways of life into question. As the nineteenth century dawned, what would be called socialism and modernism gained a new foothold.

As Msgr. Ronald Knox explained in his magnum opus, Enthusiasm (1950) — defining enthusiasm or “ultrasupernaturalism” as an excess of charity causing disunity — the fundamental principle of socialism and modernism has existed from the beginning of time. Essentially the belief that the end justifies the means, it allows anyone who believes something strongly enough to accept contradictions between what reason demonstrates and what is held by faith. This creates what G.K. Chesterton called “the double mind of man.”

It is, however, never permissible to redefine natural law derived from reason or religious doctrine held by faith, even to gain what seems to be the “greatest good.” Contradictions put faith and reason in conflict, instead of allowing one to guide and illuminate the other.

Capitalism (defined here as concentrated capital ownership) helped create the conditions that led to socialism. Socialism, however, was first proposed after the French Revolution as a replacement, not for capitalism, but for Christianity, particularly Catholicism, as explained in Henri de Saint-Simon’s 1825 book, Le Nouveau Christianisme. As la démocratie religieuse — “the Democratic Religion” — socialism was intended to supplant all traditional political, domestic, and religious arrangements.

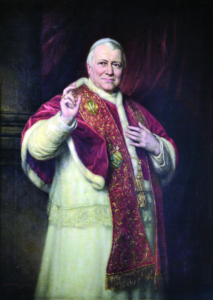

Pope Pius IX (1846-1878), the longest-reigning Pope in history.

The goal was to abolish government, marriage and family, and religion, merging everything into “the Kingdom of God on Earth.” Under various labels, e.g., “the New Christianity,” “Neo-Catholicism,” “the Religion of Humanity,” the idea, according to Chesterton, was to invent a new religion under the name of Christianity. Orestes Brownson claimed that socialism, by adopting Christianity’s outward forms and language, was a heresy so subtle it could “deceive the very elect, so that no flesh should be saved.”

In 1832, Pope Gregory XVI issued the first social encyclical, Mirari Vos, condemning the heresy.

In 1834 he issued Singulari Nos, describing the heresy as rerum novarum — “new things.” Chief among the new things was “the theory of certitude” of a renegade priest, Félicité de Lamennais, considered by some as the founder of liberal Catholicism, who said that reason resides in the collective, instead of in individual human persons. It can only be discerned by the Pope, who is infallible in faith, morals, philosophy, and theology.

Outraged at the condemnation his ideas received, de Lamennais repudiated his priesthood, renounced Christianity, and founded his own religion of humanity.

Gregory XVI also sponsored the revival of Thomism, the rigorous philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, to educate people in the truths of religion and philosophy. In the 1840s, Msgr. Aloysius Taparelli first applied the term “social justice” in a Thomist sense. Taparelli’s concept of social justice was not a right that society has by nature – something impossible in Thomism.

Society is a human construct, so that any rights society has must come from human persons. God built rights into human nature, not into the abstraction of “humanity.” Abstractions are made by man, not by God. Human beings “abstract” (generalize) because we are imperfect and lack direct, “practical” knowledge of everything. God is omniscient, and does not abstract.

According to Taparelli, social justice is the practice of virtue by individuals within the confines of natural law as defined by the Magisterium of the Catholic Church. All that does not violate the natural law, especially the natural rights of life, liberty, and private property, should be done to benefit individuals directly, and society indirectly.

Pope Pius IX issued social encyclicals, but also attempted to reform the political system. Radicals who wanted to abolish the Church, and reactionaries who wanted to return to a mythical past, both thwarted his efforts, leading to the loss of the Papal States.

As a religion, socialism requires acceptance of modernist doctrine. Recognizing this, Pius IX called the First Vatican Council, which defined two authentic Catholic doctrines, both directed against de Lamennais’s theory of certitude, but also at socialism and modernism as a whole. These were papal infallibility and the primacy of reason.

Infallibility was defined not to expand the scope of the doctrine, but rather to limit it to faith and morals, and then only under certain conditions. Defining the primacy of reason — that knowledge of God’s existence and of the natural law can be known by human reason alone — made it clear that nothing held by faith can contradict reason, any more than reason can contradict faith.

Pope Leo XIII (1886-1903), the Pope who published the great encyclical Rerum Novarum on social issues in 1891.

For more than a decade after his election, Pope Leo XIII continued Pius IX’s program, but something was missing. Doctrinal definitions and political reforms did nothing to improve people’s daily lives. The Church lost ground to the new things that promised a Heaven on Earth if only Christianity was transformed or abolished and socialism instituted.

In 1891, however, Leo XIII issued Rerum Novarum, a new type of social encyclical proposing a specific program to counter socialism and modernism. He declared the conflict created by socialism can only be resolved by empowering “as many as possible of the people” with capital ownership.

Based on his practical experience as governor of Benevento and Perugia, Leo XIII recognized that a just society and spiritual growth and development require material needs be met in a manner consistent with natural law and befitting the demands of individual human dignity. This is not by making people dependent on the State or a capitalist élite for their material needs (except as an expedient in an emergency), but by making it possible for people to meet their own needs through their own efforts, which can ordinarily be done only by owning capital.

There was no flaw in the pope’s principles in Rerum Novarum, but there was a serious problem with the practical program he outlined. The only means Leo XIII mentioned by which people could acquire ownership were inheritance and saving out of increased wages. Inheritance doesn’t work if there is nothing to inherit, and raising wages without a corresponding increase in productivity raises the price level, making saving even more difficult.

As a result, capitalists dismissed expanded ownership as a prudential suggestion, while socialists claimed the encyclical endorsed socialism by redefining private property. Both confused the principle of private property with the suggested means to acquire ownership. Socialists touted Rerum Novarum as “the living wage encyclical” and a new manifesto for Christian or democratic socialism.

Pope Pius XI (1922 1939), who reigned between the two terrible world wars of the 20th century

Pope Pius XI posited “the Reign of Christ the King” to oppose the socialist “Kingdom of God on Earth.” He defined social justice as a particular virtue by means of which organized human persons restructure the institutions of the common good to conform to the demands of human dignity. He also stressed the importance of expanded capital ownership, but again in a way that allowed both capitalists and socialists to ignore it.

Neither Leo XIII nor Pius XI was aware that relying on cutting consumption to finance new capital creates an “economic dilemma.” If enough money is saved to finance new capital, there is insufficient demand to justify the capital financially. If there is demand for additional production, there is not enough saved to finance it.

In 1958 in The Capitalist Manifesto, Louis Kelso and Mortimer Adler resolved the problem by proposing to make everyone a capital owner by using “future savings,” i.e., capital that pays for itself out of its own earnings. Instead of cutting consumption in the past to generate investment funds, increase production in the future. The rich invented commercial and central banks to do this. Kelso and Adler proposed that this system be used to benefit everyone instead of just the rich (capitalism) or the State (socialism) — a just, third way of economic personalism to replace capitalism and socialism.

As refined by the interfaith Center for Economic and Social Justice (CESJ, www.cesj.org), what we call the Just Third Way of Economic Personalism is based on the three principles of economic justice derived from natural law:

- Participative Justice, the input principle, “from each according to his productive contributions through his labor and capital,”

- Distributive Justice, the out-take principle, “to each according to his labor and capital contributions,” and

- Social Justice, the feedback and corrective principle that repairs the institutional environment whenever anyone is denied equal opportunity to contribute to production through his labor and/or capital, or from receiving his just due according to his contributions. The three principles of economic justice must be understood as integrated elements of a system if they are to be effective. Applying these principles gives the four policy pillars of a just market economy:

- Widespread direct capital ownership, individually or in free association with others (the “fatal omission” from the major schools of economics today),

- A limited economic role for the State, so that economic power resides in all the citizens and the State remains economically dependent on its citizens,

- Free, open, and non-monopolistic markets, within a strong juridical order as the best means of determining just wages, just prices, and just profits, and

- Restoration of the rights of private property, especially in corporate equity.

The four policy pillars provide the fundamental guidelines for establishing laws and practical measures to create a truly personalist economy. Guided by the natural law principles of Catholic social teaching, the Just Third Way has the potential to restructure the social order in a way that respects the dignity of every human person.

Ironically, the Second Vatican Council was called to continue the work of Vatican I and settle the problems caused by the new things. Evelyn Waugh believed that Cardinal Roncalli chose the name John XXIII to emphasize his opposition to the New Christianity.

Modernist attitudes (if not explicit modernism), however, permeated the Council deliberations. The language of the Council documents, while orthodox, could be — and was — given unorthodox interpretations. This opened the floodgates to abuses too numerous to list.

By identifying the real problem — bad ideas embodied in socialism and modernism — and recognizing the potential of the Just Third Way to restore respect for human dignity through individual empowerment, the way may be open to achieve the goal of Catholic social teaching: the just restructuring of the social order in a way that respects the dignity of the human person. Pope Francis might want to consider a new encyclical on economic personalism, and even convene another council to deal with the new things in a more effective way.

*A graduate of Notre Dame, Michael D. Greaney is co-author with Dawn K. Brohawn of Economic Personalism: Property, Power and Justice for Every Person (2020) published by Justice University Press. As Director of Research for the interfaith Center for Economic and Social Justice in Arlington, Virginia, he participated in a Vatican seminar on the importance of widespread capital ownership in combating global poverty, and co-edited the compendium, Curing World Poverty: The New Role of Property (1994). Among other books, he has written So Much Generosity (2013) about the fiction of Cardinals Wiseman and Newman and Msgr. Robert Hugh Benson, Easter Witness (2016) about the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916, and Ten Battles Every Catholic Should Know (2018) from St. Benedict Press.

*A graduate of Notre Dame, Michael D. Greaney is co-author with Dawn K. Brohawn of Economic Personalism: Property, Power and Justice for Every Person (2020) published by Justice University Press. As Director of Research for the interfaith Center for Economic and Social Justice in Arlington, Virginia, he participated in a Vatican seminar on the importance of widespread capital ownership in combating global poverty, and co-edited the compendium, Curing World Poverty: The New Role of Property (1994). Among other books, he has written So Much Generosity (2013) about the fiction of Cardinals Wiseman and Newman and Msgr. Robert Hugh Benson, Easter Witness (2016) about the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916, and Ten Battles Every Catholic Should Know (2018) from St. Benedict Press.

He has appeared on EWTN Live with Father Mitch Pacwa and EWTN Bookmark with Doug Keck. A member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, he sings in the Washington Men’s Camerata and the St. Thomas More Cathedral Choir in Arlington, Virginia.

Facebook Comments