Similarities abound between the current theological chaos in the Church and that of the fourth century

By Joseph Tamayo

St. Athanasius of Alexandria.

Today, for most people the word “heresy” refers to bygone, forgotten quarrels. Heresy is therefore thought to be of no contemporary interest because it deals with matters no one now takes seriously. If a man speaks of heresy and the powerful effect it has had on history, and still does have, he will hardly be heard. Despite the common indifference to it, heresy is of the highest importance to the individual and to society. In its particular meaning (which is that of Christian Doctrine), heresy is of special interest to anyone who wishes to understand Europe, its history and the history of the Church.

What is “Heresy?”

What is a heresy? According to Webster’s Dictionary, heresy is a) adherence to a religious opinion contrary to Church dogma, and b) denial of a “Revealed Truth” by a member of the Roman Catholic Church (1). Heresy can also be defined as the dislocation of some complete and self-supporting scheme by a novel denial of some essential part of the belief system (2). The word “heresy” comes from the Greek word haireo, the first meaning of which was “I grasp or seize”; later it came to mean “I take away” (3).

There are two types of heresy: material heresy and formal heresy. In Catholic theology, a material heresy refers to an opinion objectively contradictory to the teaching of the Church which, as such, is heretical but is uttered by a person without knowledge of its being so. In formal heresy, the person believes or teaches the falsehood which is contrary to Catholic doctrine with full knowledge and forethought.

Arianism was the first of the great Christological heresies to seriously threaten the Church. Arianism proposed that Jesus, as the Son of God, was created by God. It was proposed early in the 4th century by the Alexandrian priest named Arius. Arianism is often considered a form of Unitarian theology because it stresses a belief in God the Father at the expense of the Trinity, the doctrine of three distinct persons in one Godhead. The Bible says in John 3:16: “For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son” (4). The problem with Arius and the other heretical bishops was that they misinterpreted “begotten.” Arius and the other heretic bishops made the mistake of imposing “time” on God, forgetting that God lives outside of time. They believed that, like human fathers, God the Father existed prior to the Son in time, not just in concept.

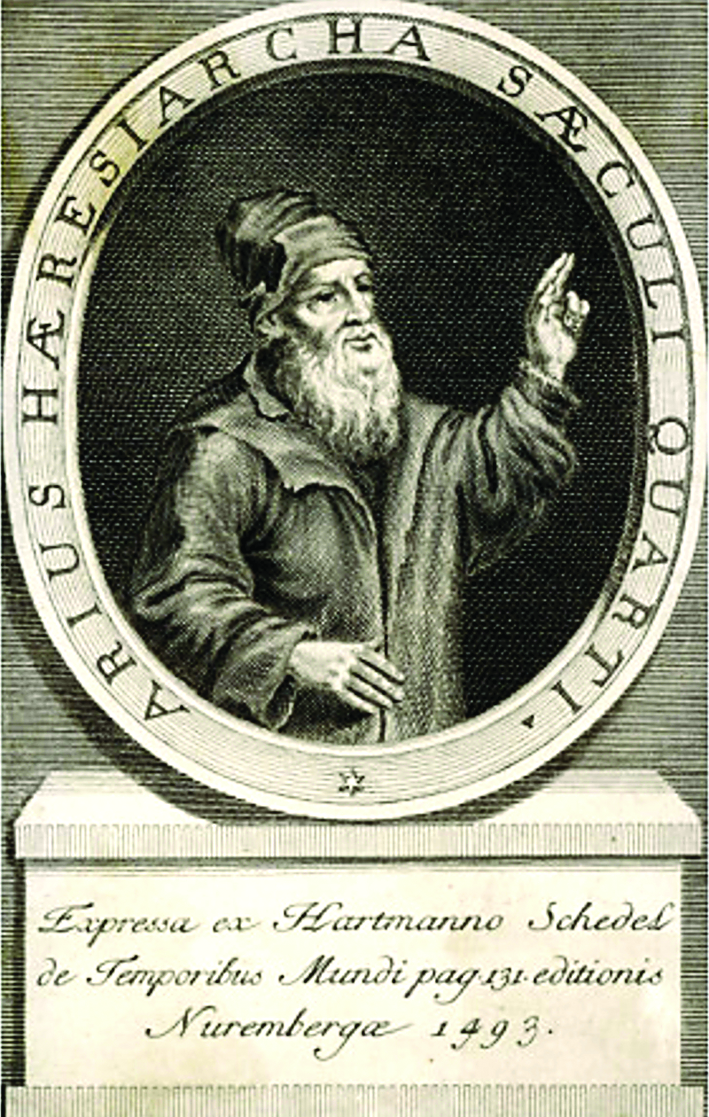

Arius. The inscription says, “Arius, Heresiarch of the 4th Century.”

Arius was a Greek-speaking African cleric. He was originally a student at the Exegetical School in Antioch.This school was a school of Sophists who were known for studying Greek philosophy. St. Cardinal John Henry Newman said the educational system at Antioch was the “birthplace” of this heresy (5).

Arius studied under Lucian the Martyr. Early in the 4th century, Arius began to teach his heresy. He was excommunicated in 311AD by the bishop of Alexandria, but the bishop’s successor, Achilles, readmitted him to Christian communion in 313 AD. He was made a priest of the Baucah district in Alexandria. Arius became famous some years before the Roman Emperor Constantine’s victories which freed the Christians from persecution.

Arius was a man of great eloquence and driving power. He possessed a great deal of ambition, rationalism and arrogance. Arius went from Egypt to Caesarea in Palestine, spreading his rationalizing and Unitarian theories with zeal.

Arianism would have been a dangerous warping of the Catholic faith if left unchecked; it declared that Our Lord was as much of the Divine Essence as was possible for a creature, but that he was nonetheless a creature. It sprang from the desire to visualize clearly and simply something which is beyond the grasp of human vision and comprehension, namely, three Divine persons, all uncreated in one Godhead, the Triune God (6). It inevitably would have led in the long run into mere Unitarianism and the treating of Our Lord as the last prophet, but nonetheless, only a prophet (7).

According to Arianism’s opponents, especially St. Athanasius, Arius’ teachings reduced the Son to a demigod, reintroduced polytheism (since worship of the Son was not abandoned), and undermined the Christian concept of redemption, since only he who was truly God could be deemed to have reconciled humanity to the Godhead (8). This also would eventually allow room for him to have a sinful nature, or at least the possibility of sin in his life. We are seeing examples of this today, such as the denial of Christ’s divinity. Now we have examples of Syncretism, where all religions are treated as inspired by God. Such heresies must be rejected by the faithful as our Early Church Fathers and their predecessors have done.

The Council of Nicaea

An icon depicting the Emperor Constantine, accompanied by the bishops of the First Council of Nicaea (325), holding the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381.

Arius was propagating his ideas in earnest and began to canvass for support among the clergy and lay people in Alexandria and beyond.

In 321 AD, a local synod of bishops in Egypt and Libya deposed Arius and his allies, but this didn’t stop him. In 325 AD, the Emperor Constantine convened the First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea to deal with this severe crisis.

The Council excommunicated Arius, banished him and condemned his teachings.

The Council created The Nicene Creed which states that the Son (Jesus) is homousion to Patri — a Greek phrase which is translated “of one substance with the Father.” The Greek word homousion is important because it perfectly means “of the same substance”: the same essence, identical in every respect; not different one iota!!

During this time, another great figure appeared, St. Athanasius of Alexandria. St. Athanasius was born in 296 AD. He was learned in philosophy and Neoplatonism, but his special interest was in the Holy Scriptures. He was courageous and unflinching in the face of danger or adversity. St. Gregory the Theologian called him “the pillar of the Church.” In 325 AD, St. Athanasius served as the secretary to the Bishop of Alexandria at the Council of Nicaea. Under the bishop, St. Athanasius wrote many letters and documents condemning the Arians.

Another great figure at this time was St. Hosius of Alexandria, who helped propose the idea of homousion for the Creed. He also wrote letters to the Emperor Constantine to influence his opinion in favor of the orthodox bishops. Under Constantine, the Council of Nicaea included in the Creed the phrase “begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father,” which became a dogma of the Church. Some time after the Council, St. Athanasius succeeded St. Alexander and became bishop of Alexandria. In 337 Constantine died, and those Church leaders who had supported Arius, as well as Arius himself, attempted to return to their churches and sees and to banish their enemies. They were very successful.

The Empire was divided under two rulers at this time. The anti-Arian Emperor Constans ruled in the West and the West remained mostly orthodox, while pro-Arian Constantius II ruled in the East. At a Church Council at Antioch in 341 AD, an affirmation of the faith that omitted the homousion clause was issued. Under Constantius in the East, the Arians gained power and influence.

END PART I

1 Webster’s Dictionary

2 The Great Heresies by Hillaire Belloc

3 Ibid.

4 Douay Rheims Bible: John 3:16

5 Arians of the 4th Century by St. John Henry Newman

6 Belloc, Heresies

7 Ibid.

Facebook Comments