Look to the small, the unconsidered trifle, for the great and hidden things of God.

By Prof. Anthony Esolen

“Let the earth bring forth grass, the herb yielding seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after his kind, whose seed is in itself” (Genesis 1:11)

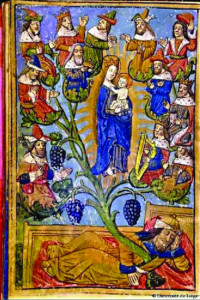

“The kingdom of heaven,” says the Lord, “is like to a grain of mustard seed, which a man took, and sowed in his field.” It is the least of all the seeds, but when it grows, it is no mere herb on the ground, but it becomes a tree, “so that the birds of the air come and lodge in the branches” (Mt. 13:31-32).

Optimism, that huckster, wheedles us into placing out trust in sure bets, things that will be too big to fail. The villain in Herman Melville’s The Confidence-Man plays upon the all too human desire to be in the know, to persuade his marks to enter into trusts that are both financial and moral — financially and morally dubious, that is, but what a payoff there will be in the end, and soon! You must have confidence, he says.

Jesus does not ask us to have confidence in our fellow men. He had no such, not even when people were eager to see him because of the wonders he had done: “But Jesus did not commit himself unto them, because he knew all men, and needed not that any should testify of man: for he knew what was in man” (Jn. 2:24-25). Jesus does not ask us to have confidence in the future, not even when it appears embodied in the Temple itself: “There shall not be left one stone upon another, that shall not be thrown down” (Mk. 13:2). We surely must not be such fools as to have confidence in ourselves: “When ye shall have done all those things which are commanded you, say, We are unprofitable servants” (Lk. 17:10)

In Christ alone is our hope. But he tells us straight off that we must expect to be persecuted: “And ye shall be hated of all men for my name’s sake” (Mt. 10:22). Where, then, is the hope? “Comforter, where, where is your comforting?” cries the poet Hopkins. “Mary, mother of us, where is your relief?”

Of course we might say that the hope is not now but in the age to come, not here but in the kingdom of heaven, not in fallen man but in man redeemed in Christ. And that is true, but it is not the whole truth. For the kingdom of heaven is like to that mustard seed.

Think of the wonder that is the seed. It is a single corn, a speck, a grain of dust. Yet somehow it holds within itself great things to come. It is the bearer of life and its promise. Seeds are the first fruits of God’s creation: “Let the earth bring forth grass, the herb yielding seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after his kind, whose seed is in itself” (Gen. 1:11).

What does the seed of a tree have to do with us? Here we must be like those who restore bright and colorful works of art, scrubbing from their surfaces the grime of a hundred years of smokestacks, so that tempera may be bold and marble may gleam again. The authors of Scripture thought as poets think, not as members of an industrial committee. For the committee, and I am thinking of committees responsible for what we English-speaking Catholics read in our Bibles or hear at Mass, the seed is a seed and nothing more, and sometimes it is not even a seed, but something workaday that the seed is supposed to represent: the seed, like other poetic images, is an envelope to be opened and then forgotten.

Not so for Scripture; not so for the sacred poet’s world and its flowers of meaning. Think of the time when Abram separates from his nephew Lot, giving him first choice of where to take his herds, and Lot chooses the well-watered plains of Sodom before its destruction. At that point God speaks to Abram, showing him the land roundabout him in every direction as far as he can see. “To thee will I give it,” says God, “and to thy seed for ever” (Genesis 13:15).

Abram, to be re-named Abraham, the father of many, is the “herb yielding seed,” and we too in faith are the seed of Abraham.

You won’t hear that word seed in the lectionary. It is too physical, too specific for comfort, too pregnant with allusion and echo and image. You will hear of descendants instead. Yes, that is what the sacred poet intends. But that is not the whole of what he intends. Seed means descendant, but descendant is too narrow to mean seed.

The underlying metaphor has been obliterated and replaced with a word that either is not metaphorical at all, or that alters the metaphor: to descend is to come down.

God had commanded Noah to bring pairs of every kind of bird and beast into the ark, “to keep seed alive upon the face of the earth” (Gen. 7:3). The mystery of the seed is that it contains the tree within it. The seed is a holy thing. “Thy seed shall be as the dust of the earth,” says God to Jacob when he lies dreaming on the plains of Padan-aram, transforming into a blessing the original curse laid upon fallen man: “For dust thou art, and unto dust thou shalt return” (Gen. 4:19, 28:14).

We see then the filth and perversity of doing with seed what should not be done; sins against what the seed is, as when Onan spills his on the ground, “lest he should give seed to his brother,” who was slain by the Lord for his wickedness (Gen. 38:9), or as when the men of Sodom demand to know the angel visitors, knowledge that is madness and vanity and that treats seed with contempt (Gen. 19:5), or as when Lot’s daughters get their father drunk so that he will lie with them, “that we may preserve seed of our father” (Gen. 19:32), resulting in those perennial idolaters and enemies of the children of Israel, the Moabites and the Ammonites (Gen. 19:37-38).

So when we turn again to the mustard seed, that speck of dust, we find no cause to be optimistic, but every reason for hope. Abram was but an old man and an idol worshiper, living out a barren life in Ur of the Chaldees. But from his seed sprang the Tree of Life.

“Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?” asks Nathanael the guileless, apt to speak his mind (Jn. 1:46). No, nothing good does come from there, nothing except the only fully wondrous thing in the world. When Mary, who knew not man, said to the angel, “Be it unto me according to thy word,” then it was that the impetuous bridegroom sowed the seed, and it had life, as it was the source of all life, and he dwelt among us in the flesh (Luke 1:38).

It is the law of our existence that we should look to the small, the unconsidered trifle, for the great and hidden things of God, who brought the world out of nothingness. “Verily, I say unto you,” says Jesus, “except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit” (Jn. 12:24). It is not good for us to abide alone, dark and cold and inert. All the works of man alone are finally just one great heap of stones, not one of which shall remain upon another. But a seed, a single seed, is more potent than all the capitols and arches of triumph and graveyards of glory in the world.

There is our hope.What is in the smallest of the seeds? Says Chesterton:

God Almighty, and with Him

Cherubim and seraphim

Filling all eternity —

Adonai Elohim.

Anthony Esolen, Ph.D., is a faculty member and Writer-in-Residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts in New Hampshire. Dr. Esolen is a renowned scholar and translator of literature, and an author of multiple books and hundreds of articles in both Catholic and secular periodicals.

Facebook Comments