Why the use of a single, unchanging ancient language can be beneficial

By John Byron Kuhner

Latin has been back in the news recently, as most Catholics are aware, thanks to Pope Francis’ motu proprio Traditionis Custodes, calling for fairly severe restrictions on the Tridentine Latin Mass. Reaction has been politically divided, about as one would expect. If you get on some Latin Mass Facebook pages, you will find sadness and anger. If you go to Fr. James Martin’s Facebook page, people are celebrating and cheering Francis on.

I will note that I see a point in what Francis is saying. There is division in the Church. In my upstate New York parish, as in many places in America today, we already functionally had two parishes which never came together, divided by the Novus Ordo Mass.

There was the Spanish-speaking parish and the English-speaking parish. Then a new pastor came in who added a Latin Mass. This brought a whole new group of people in, who in general don’t socialize with the English-Mass people or the Spanish-Mass people.

I actually like the diversity of liturgy, but I can see the potential trouble. It would be nice to have a Mass that was the same for everyone.

The odd thing about Traditionis Custodes is that this dream of having a universal Mass was the situation until the Novus Ordo.

But from comments I’ve been reading, I think it is worth taking some time to think intelligently about how language operates in the liturgy. This whole controversy has raised some interesting questions.

First of all, why wouldn’t we want our prayers and the Mass in our mother tongue? It seems entirely rational to just have our prayers in the language we are most comfortable with. And since just about no one is as comfortable with Latin as they are with their native languages, why not simply get rid of Latin as a liturgical language? This seems rational enough.

But it is not upheld by the actual experience of the majority of human beings. India’s magnificent religious culture is sustained to this day by songs, chants, prayers, and Scriptures written in Sanskrit, a language just as dead as Latin. Tibetan Buddhists like the Dalai Lama pray in classical Tibetan from the 12th century and not modern Tibetan. Muslims pray in 7th century classical Arabic — even though Arabic has changed a great deal in the past 1400 years and the world’s largest Muslim countries (Indonesia, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Nigeria) do not speak Arabic at all. The Hebrew language appears to have passed out of daily use sometime before Latin did, but it has remained the language of prayer for all Jews to this day, whatever language they may have first heard from their parents (Hebrew was also successfully resurrected as a spoken language in the 19th century by the remarkable Eliezer Ben-Yahudah). Greek Orthodox Christians still celebrate the Mass in ancient Greek — the same Koine Greek the New Testament was written in.

The idea of preserving prayers in an old language — and not updating them to keep up with the times — is not an eccentricity of Roman Catholicism. It is at the heart of most of the world’s most successful religions. Even in the Protestant world, English speakers have kept the King James Bible to this day, and a whole host of archaic usages; Germans have kept the Luther Bible and its New High German.

Such a widespread phenomenon must mean something. It may seem to go against reason, but the idea of a sacred language different from the language of everyday life appeals to human beings. I can say from my own experience that prayer in Latin and Greek actually does seem to have a different effect on me: it pulls me out of my daily life, places me sub specie aeternitatis, where I have room to reflect on what is most important to me. Joseph Campbell — the furthest thing from a “traddy” Catholic — wrote about this:

“There’s been a reduction, a reduction, a reduction of ritual. Even in the Roman Catholic Church, my God, they’ve translated the Mass out of the ritual language into a language that has a lot of domestic associations. Every time I read the Latin of the Mass, I get that pitch again that it’s supposed to give, a language that throws you out of the field of your domesticity… They’ve forgotten what the function of a ritual is: it’s to pitch you out, not to wrap you back in where you have been all the time.”

Human artifacts and cultural productions point the mind always to the era of their origin. Language acts this way as well. Sometimes this makes sense: the prayers and Scriptures of Islam hearken back to the days of Muhammad, who is considered the perfect embodiment of the Muslim life. The Aramaic of the Syriac Churches, and the Greek of the Orthodox Church, come directly from the times of Christ. When there is no particularly obvious reason for making the language of one era the language of prayer for later eras, people often resort to mythic reasoning: some Hindus maintain that Sanskrit is actually the language of the gods, just as some Jews maintain that Hebrew was the language spoken by God to Adam and Eve. Latin has seen this mythic reasoning too, that it is the “language of the angels.” And indeed, in Christian terms, Latin’s claim to sacrality is not as great, quantitatively, as Greek or Aramaic, which were likely spoken by Jesus. But Latin has the same type of claim, qualitatively, as Greek and Aramaic: it is one of the languages of the days of Jesus. The Roman centurion he met spoke it; Pilate spoke it; when Paul had to defend himself in court in Rome, or when Peter heard the crowds in the Eternal City, Latin was the language of the day. And now Latin has been further consecrated by a whole host of saints and believers through the subsequent centuries of what has been called the Latin Rite. The Tridentine Mass makes those people present in the soul of the believer.

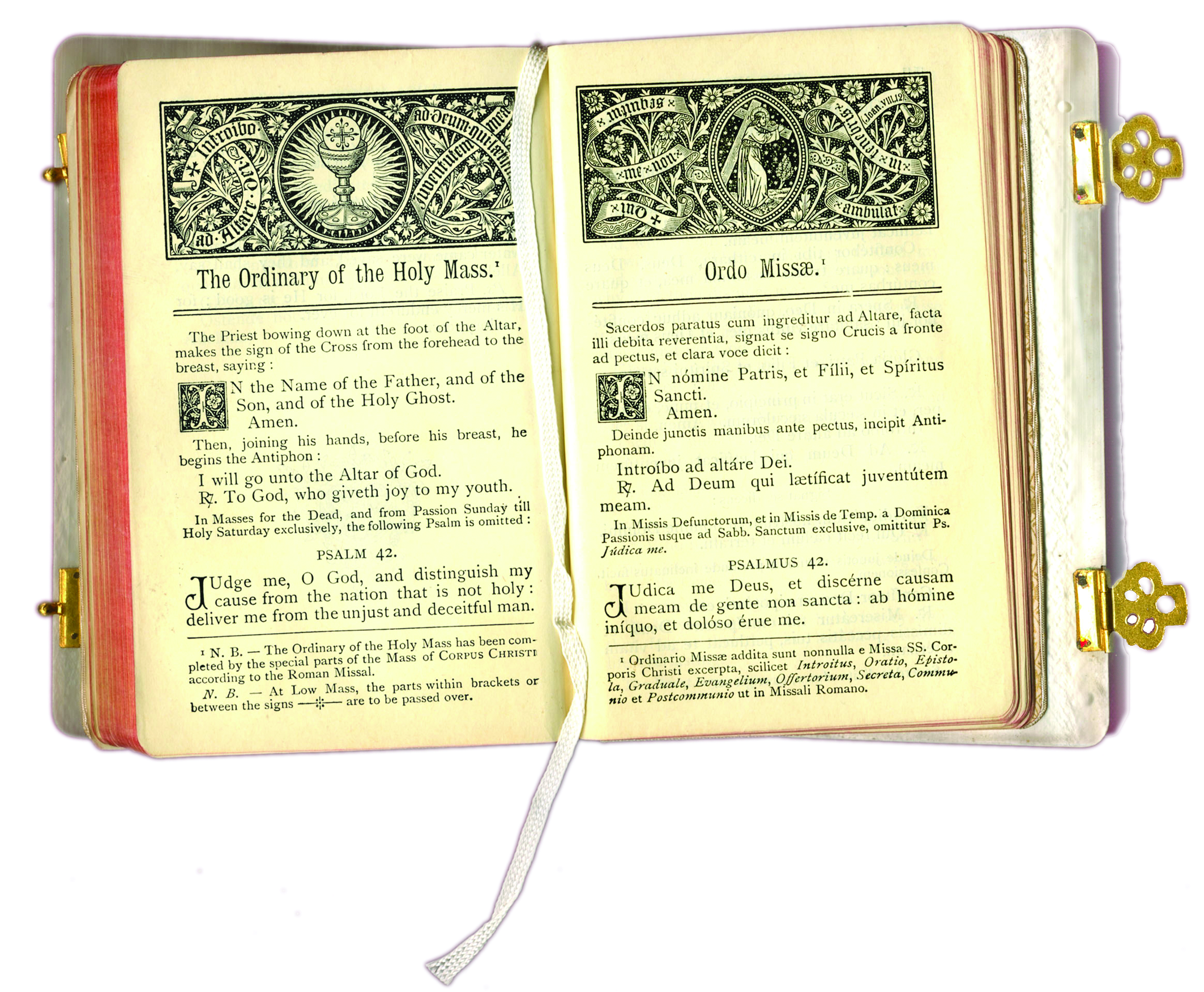

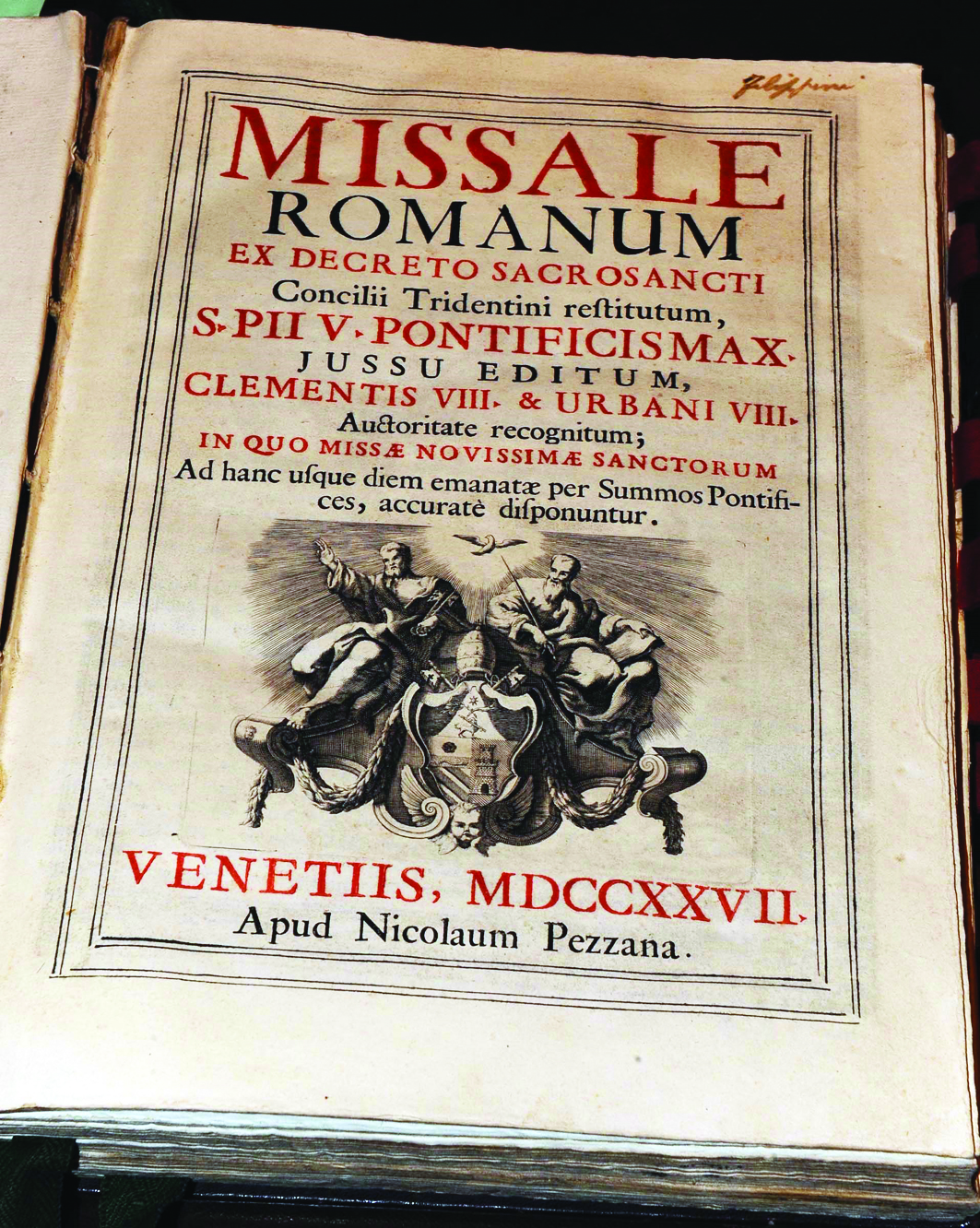

Pius V (1566-1572) in his decree Quo primum tempore of 1570 (450 years ago) promulgated the Roman Missal or Missale Romanum ex Decreto Sacrosancti Concilii Tridentini restitutum. For this reason it is called the Tridentine Missal or the “Missal of St. Pius V.” This is what we call “the old Mass”

The Novus Ordo Mass is, of course, just as much a product of its time as any other cultural product. It is a product of the late 1960s. There is no doubt that this is the single most important period in the recent history of the world, a time when so much of modern life — our language, our architecture, our entertainment, our business habits, our social mores, our sex lives, and our liturgy — developed its current form. This is the strength of the New Mass: it is firmly rooted in a culture which is still very much with us.

But many people want the patina of age on their religions. A friend of mine declared that the older a religion is, the more respectable it is: he was uneasy with the newness of Scientology, the Baha’i, or Mormonism. Many people feel that way. And it is with the older forms of liturgy that Catholics actually get to experience the venerability of their religion.

Like many Catholics, I am not an exclusive adherent of the Tridentine Rite, but I see its beauty and importance. I think that people should pray, often, in the language they are most comfortable with; but I think people should also pray, at least sometimes, in a language removed from daily associations, and know, as most of the world’s believers do, the value of having a sacred language. I think eventually people will consider it odd that for a brief period of time there were many Roman Catholics, and even several Popes, who did not understand this.

Facebook Comments