The Lord cheers the heart of my youth, not just in age, but in spirit

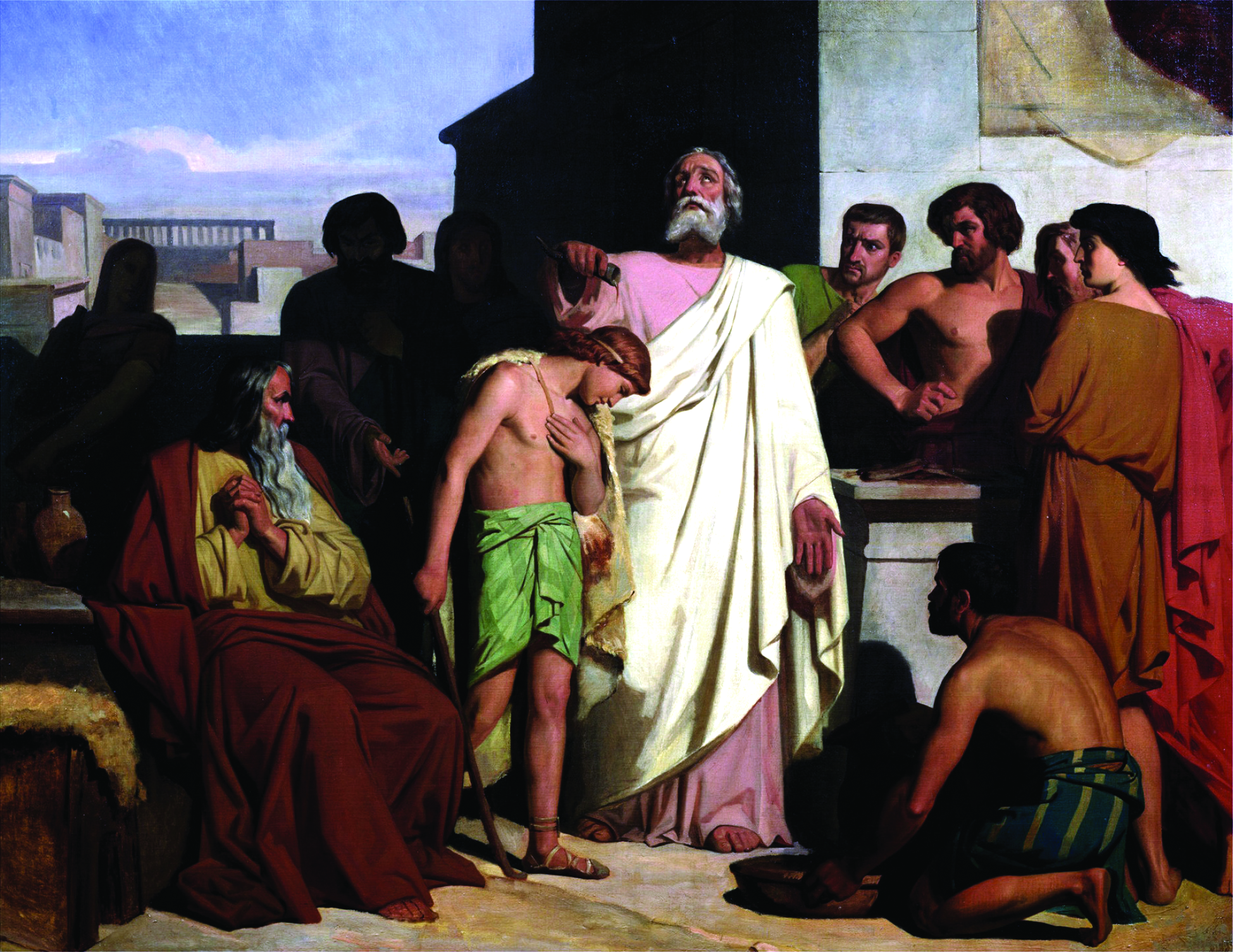

The Anointing of David by Samuel, by Félix Joseph Barrias, Musée de la Ville de Paris

“Then I shall go in unto the altar of God, of God, who gives joy to my youth” (Ps. 42:4).

By Prof. Anthony Esolen

The first time I read those words after a hiatus of forty years, I believe my heart skipped a beat, as they are so beautiful and so fitting where and when and by whom they were commonly spoken.

But I must explain. I had of course read the psalms all my life long. But the verse above does not appear in the version of the psalms which Pius XII approved for liturgical use within the Mass. It is a translation of Saint Jerome’s Latin: Introibo ad altare Dei, ad Deum qui laetificat iuventutem meam. And for that verse, Jerome follows closely the Greek Septuagint, that famous translation of the Old Testament by Greekspeaking Jews in Alexandria.

It is a part of the psalm that the priest and the altar boy would recite antiphonally at the very beginning of Mass, in the old rite. Think of the power of it, then. The priest said, in Latin, “I will go in to the altar of God,” and the altar boy responded, “To God, the joy of my youth.”

That is what they said before they began the psalm, and what they said after the psalm, just before they prayed the Confiteor, first the priest in his person, and then the altar boy in his. Within the psalm itself, the altar boy speaks the whole verse. It thus acquires a profoundly embodied and personal force. The priest was once young, too, and he hears from the server a voice of youth, the voice of a lad who may by the grace of God someday become a priest in his turn and lead the prayer for another youth, saying, Introibo ad altare Dei.

The Greek is glorious in its own right. The psalmist says that he will enter unto the thysiasterion of God — the altar, but literally, the place firmly fixed where sacrifice is made, specifically where the smoke goes up, and we may think of the censer and the intensity of the aromatic spices, gently burning. God gives good cheer to my phren, the heart, the breast as the seat of passion and will, the place of understanding and loving what is good. He cheers the heart of my neotes, my youth, not just youth in age but in spirit — my youthfulness — and thus can even an old man like me pray the prayer in earnest.

The word is affectionate in force. In this regard it resembles the Hebrew na’ar, youth, sometimes servant, but often lad: used of the boy Isaac as he climbs the mountain with his father Abraham, of the young Benjamin whom his elder brother Joseph longs to see, and of David, when the prophet Samuel anoints him to be king of Israel.

Here is the psalm-prayer in its entirety, as divided between the priest and the server. I give the translation from the old Saint Joseph Missal:

P. I will go in to the altar of God.

S. To God, the joy of my youth.

P. Give judgment for me, O God, and decide my cause against an unholy people: from unjust and deceitful men deliver me.

S. For Thou, O God, art my strength; why hast Thou forsaken me? And why do I go about in sadness, while the enemy afflicts me?

P. Send forth Thy light and Thy truth; for they have led me and brought me to Thy holy hill and Thy dwelling place.

S. And I will go in unto the altar of God, to God, the joy of my youth.

P. I shall yet praise Thee upon the harp, O God, my God. Why art thou sad, my soul, and why dost thou trouble me?

S. Trust in God, for I shall yet praise Him, the salvation of my countenance, and my God.

P. Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit.

S. As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end. Amen.

P. I will go in to the altar of God.

S. To God, the joy of my youth.

The Celestial Jerusalem and the Lamb, miniature in the Biblioteca Nazionale of Paris, France

When I go to Mass, I try to say those opening prayers silently, while people are filing in, and (if I am in an unfamiliar church) while the officials of the proceedings get ready to issue a welcome and announce their names to all and some. The psalm helps me to remember why I am there. The psalmist longs to go to the temple, the house of God in Jerusalem. I have a higher ambition. I long to go to the new Jerusalem, where the saints and angels make an eternal sacrifice of praise to God, to God who has made all things new, who gives joy to their youth. What happens on earth is a participation in what happens in that twelvegated city above. I can say, with all the greater confidence, “I shall go in unto the altar of God,” because Jesus, the Lamb of God, has sacrificed himself on the altar of the cross for my sins, and thus prepared a place for us there.

One more point – a crucial one, I think. Often when you go to Mass, you are not feeling joyful at all. There is trouble at work. Your child has disappointed you. You have done wrong, and you know it. Nor do you feel like pretending that all is well. That kind of pretense is exhausting, and after you have tried to keep a frozen smile on your face, the disillusionment comes, and you say, “Maybe I do not belong here after all.” For joy cannot be forced. You can be wangled into a good mood, but not into joy, that quiet, soaring fullness of life.

Hence it is fitting that the opening psalm for Mass should embrace the trouble, the doubts, the cry of the anguished heart, “Why have you forsaken me?” But the psalmist also recalls the light of God, the light that has now and in the past led him to the holy mountain. He begs that God may shine forth that light once more, and then he ends with praise, tenderly rebuking his own heart for its sadness, and affirming his trust in the God of his salvation.

And what a bold choice it is, to bracket the prayer with that beautiful verse. We begin and we end with the affirmation. Think of the words of Jesus: “In the world you shall have trouble, but fear not, for I have overcome the world” (Jn. 16:33).

Facebook Comments