Can Catholics and Orthodox finally celebrate the Resurrection together?

By Zachary Naccash

Since at least the Second Vatican Council, it has been a goal of the Catholic Church to come to an agreement with the Orthodox Churches regarding the date of Easter. In recent years Church leaders on both sides have repeatedly pointed at the year 2025 as a prime opportunity to make that goal a reality.

One reason is that it is one of relatively few years in which the Catholics and the Orthodox coincidentally celebrate Easter on the same day.

The second and more important reason, however, is that 2025 is the 1700th anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea — the first Ecumenical Council of the Church, which first set down how the whole Church was to calculate when to celebrate Easter. Those two features, together with the ecumenical progress made between Catholics and Orthodox over the past century, make 2025 a natural time to attempt this substantial step towards Christian unity.

Since the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church has been broadly open to adopting any method of determining the date of Easter, and even to the prospect of setting a permanent date for it, so long as the rest of the Christian world (and especially the Orthodox) agreed. As Pope Francis put it in a 2022 message to Assyrian Church of the East Patriarch Catholicos, “On this point, I want to say – indeed, to repeat – what Saint Paul VI said in his day: We are ready to accept any proposal that is made together.”

Not everyone, however, is quite so sanguine about this approach. For the past several years, each spring has seen a flurry of articles written on this topic from both Catholic and Orthodox authors. While many share the Pope’s enthusiasm for a single Paschal celebration, others on each side of the aisle have expressed concerns and objections. As we are now only one year out from Nicaea’s anniversary, it behooves us to reflect on the goods to be gained from efforts to arrive at a common date for Easter as well as on some of the pitfalls to be avoided.

Why the Catholic and Orthodox dates diverge

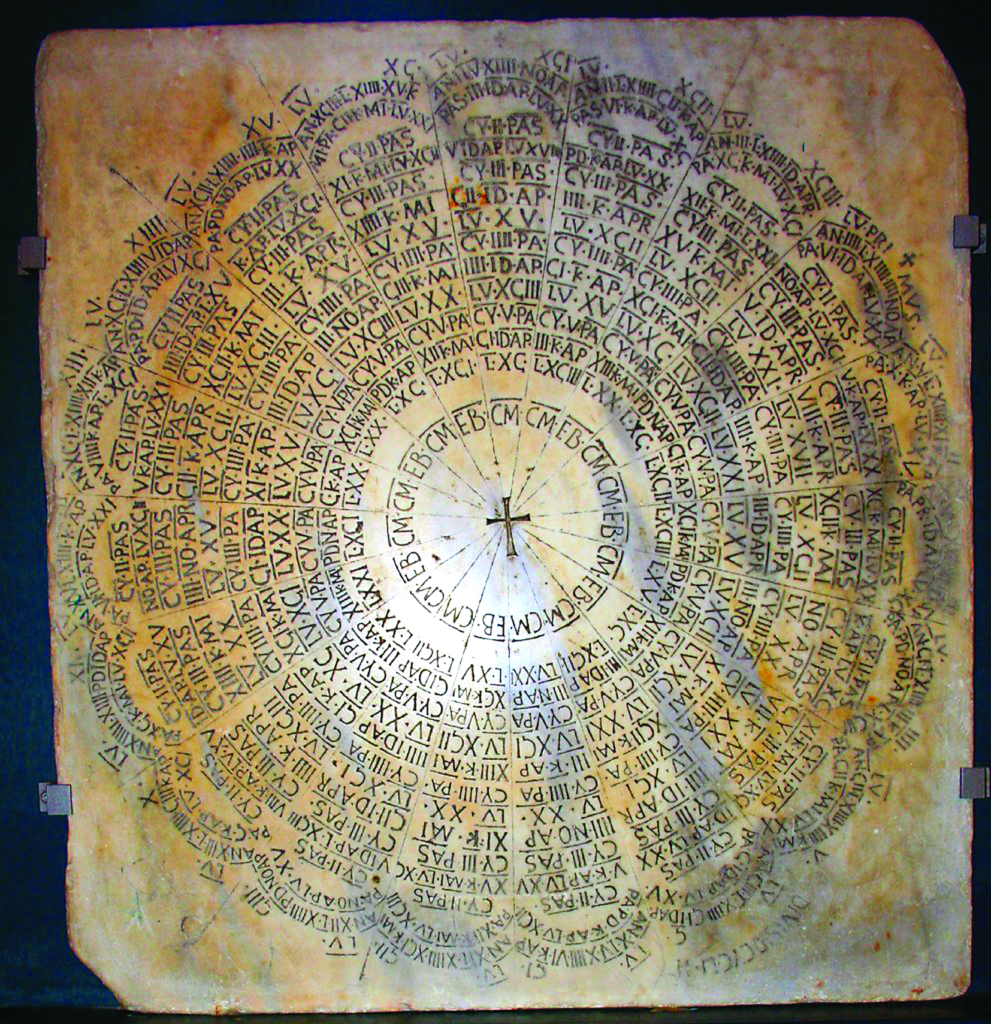

A calendar of the dates of Easter, for the 95 years from 532 to 626, marble, in the Museum of Ravenna Cathedral, Italy

The full story of how Eastern and Western Christians came to celebrate Easter at different times is a long and complex one. The short answer is that it comes down mostly to the issue of astronomical mapping — which is to say, calendars. In 325, in response to disagreements regarding when Easter ought to be celebrated, the Nicaean Council decreed that it should take place on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox. Given this directive, calculations were made using the Julian calendar, in use at the time, to determine when Easter would be celebrated.

At the time this worked perfectly well, but over time, due to inaccuracies in the way the Julian calendar measured years, the calendar began to drift away from the observed astronomical phenomena. This gradual drift of the calendar meant that by the 16th century, the calendar year was a full 10 days off. And the negative impact of this drift was not confined to liturgical celebrations — it had wide ranging effects including, for example, throwing off agricultural timing. Such issues eventually caused Pope Gregory XIII to commission the creation of a new calendar that more accurately matched and predicted astronomical phenomena. That calendar came to be known as the Gregorian calendar and is the one used today by western Christians for liturgical purposes (including setting the date for Easter), as well as by nearly every country in the world for secular purposes.

While the Orthodox were not unaware of the issues with the gradually slipping Julian calendar, a variety of factors prevented them from adopting the Gregorian calendar or producing an updated calendar of their own. The two biggest factors seem to be the adamant (and often praiseworthy) adhesion to tradition that is typical of Orthodox Christians. The other is the relatively fragmented nature of their communion — for better or worse, they lack the centralized governing authority Catholics ascribe to the papacy and, as a result, they have historically found it difficult to reach any pan-Orthodox agreements.

When, in the early 20th century, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople introduced the Revised Julian Calendar — which updated the fixed feasts on the Julian calendar to match the Gregorian by shifting the dates by several days, but left the Paschal calculations the same — not only did he fail to convince every Orthodox church to adopt the new calendar, its adoption by some led to a number of minor schisms within Orthodoxy. Even to this day, the Orthodox world is divided between those who follow the Julian and those who follow the Revised Julian.

“We beseech the Lord of Glory that the forthcoming Easter celebration next year will not merely be a fortuitous occurrence, but rather the beginning of a unified date for its observance by both Eastern and Western Christianity…indeed, it is a scandal to celebrate separately the unique event of the one Resurrection of the One Lord.”

— Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, in a March 31, 2024 homily

Possible solutions

What then is to be done if Eastern and Western Christians are to agree on a common date for Easter? Several solutions have been proposed and each has its own respective pros and cons. One option is for the Catholics to simply return to the use of the Julian calendar. This solution has the benefit of being the easiest to accomplish, given the Catholic Church’s centralized governance.

However, it has one intolerable drawback— the Julian calendar simply does not reflect astronomical reality. A return to its use would seem to misrepresent the relationship between faith and reason.

Our faith is not contrary to reason but builds upon it, and this relationship should be reflected in the liturgical life of the Church. Since the building blocks of all calendars are observable natural phenomena (the rotation of the earth on its axis, the cycle of the moon, and the orbit of the earth around the sun), any calendar is a bad one if it poorly matches those phenomena, just as a map is a bad one if it poorly matches geographical landmarks. All calendars miss the mark to some extent and, over extended time frames, those discrepancies build up so that calendars drift away from the reality of which they are a map. The fundamental problem with using the Julian Calendar over the Gregorian Calendar is not the fact that the Gregorian Calendar is a more accurate map (though it is), the problem is that over the centuries the Julian calendar has drifted nearly two weeks away from astronomical reality.

Another possible solution is for the Orthodox to simply adopt the Gregorian calendar that most Catholics already use. While this solution has the benefit of maintaining an accurate correspondence between the Church’s calendar and the astronomical data, it could be more difficult to elicit Orthodox agreement to it. The Orthodox are, in general, more wary of ecumenical efforts than Catholics are and that is especially the case where it appears that they are simply being assimilated to Catholicism. Given that the Gregorian calendar is one that was developed and promulgated by Catholics without input from the Orthodox, it is difficult to imagine that they would be comfortable in simply adopting it at this point.

The third possibility is that the Catholics and Orthodox together produce a new way of determining the date of Easter. One method for this that has been discussed is to jettison altogether the complicated calculations for a moveable Easter and settle upon a single, fixed Sunday to celebrate every year (proposals usually suggest the second or third Sunday of April). While this solution would have the benefit of avoiding the appearance of one side “winning” as well as the issue of calendar drift, it does seem to untether the celebration of Easter from ancient tradition in a way that cannot but be seen as disappointing.

In the end, the problem remains a thorny one, with no clear path forward. Even so, the reward of a more unified Christendom is worth the effort of trying. Christ’s prayer that “they may be one, even as we are one,” ought to be the prayer of every Christian — and there is no doubt that any agreement on a common date to celebrate our Lord’s Resurrection would be a significant step towards making that a reality.

Facebook Comments