“We might, perhaps, set out on a part of the journey together”: these words are the heart of the letter that Pope Francis wrote to the Italian journalist Eugenio Scalfari on September 11, and they reveal a central part of the Holy See’s current strategy for dealing with a Western culture which has entered a profound moral, economic, demographic, philosophical and spiritual crisis. And that strategy is to engage in dialogue in order to effectively present a Gospel message which could heal the crisis and lay the basis for a new flowering of Western culture, if it is embraced…

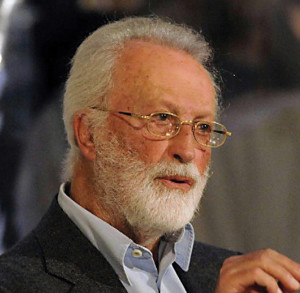

Eugenio Scalfari

Scalfari is not just anybody. He is the co-founder of the daily newspaper La Repubblica, a prominent organ of secular humanist thinking in Italy. As such, Scalfari is one of the leading “opinion-makers” of the past two generations in Italy, and thus one of the most important shapers of modern Italian culture. The letter was published on the paper’s front page with the title “My letter to those who do not believe.”

Two weeks later, on September 24, the same newspaper published a letter from Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI to the Italian mathematician Piergiorgio Odifreddi, who had written a skeptical book on Jesus, under the title: “Dear Odifreddi, I will tell you who Jesus was.”

These unusual “letters from Popes” to private individuals created a sensation in Italy, and prompted considerable commentary.

(It is whispered that the hand of Benedict XVI is hidden “between the lines” of the first letter, and that Francis encouraged the publication of the second.)

These two letters — despite their different recipients — have a common aim: to open a fruitful dialogue between Christianity and “modernity.” This has been the Church’s aim since the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), but these letters suggest an emerging shift from an “official” or “institutional” dialogue (conducted by commissions and events like the “Courtyard of the Gentiles” of the Pontifical Council for Culture) to a “personal” dialogue, involving listening and answering. And both the German Pope Emeritus and the new Argentinian Pope have defended, praised, and sought to implement this path throughout their lives.

Though addressed to specific individuals, both letters were conceived as texts to be read by a much wider audience, and to open a dialogue between Christian faith and the secular world view which has become dominant in the West.

In his letter to Scalfari, Francis sets out from his personal experience of faith and of coming to believe in God. He stresses that “faith is not intransigent, but grows in respectful coexistence with others” and that “only faith launches us on a journey making witness and dialogue possible. This is the spirit that animates the words that I write to you.”

The front page of La Repubblica with the headline: “The Pope: My Letter To Those Who Do Not Believe.”

Benedict, in his letter, exemplifies the method of real dialogue, answering each and every point of Odifreddi’s essay, without sparing criticism and even irony (“What you say about the figure of Jesus is not worthy of you as a scientist. I invite you to become a little more competent in historical matters”). And he concludes: “My criticism of your book is in part a harsh one. But frankness is part of dialogue; only in this way can knowledge grow (…). In any case, I appreciate that you (…) have sought such an open dialogue with the faith of the Catholic Church (…)”.

The September 11 letter of Pope Francis to Scalfari was a reply to a two-part letter Scalfari had written to Francis and published in the pages of his newspaper on July 7 and August 7.

“I would cordially like to reply to the letter you addressed to me from the pages of La Repubblica on July 7, which included a series of personal reflections that then continued to enrich the pages of the daily newspaper on August 7,” Francis began. “First of all, thank you for the attention with which you have read the encyclical Lumen fidei [Note: the first encyclical of Pope Francis, published on June 29.] In fact it was the intention of my beloved predecessor, Benedict XVI, who conceived it and mostly wrote it, and which, with gratitude, I inherited, to not only confirm the faith in Jesus Christ for those who already believe, but also to spark a sincere and rigorous dialogue with those who, like you, define themselves as ‘for many years being a non-believer who is interested and fascinated by the preaching of Jesus of Nazareth.’

“Therefore, without a doubt it would seem to be positive, not only for each one of us, but also for the society in which we live, to stop and speak about a matter as important as faith and which refers to the teachings and the figure of Jesus.”

Pope Francis (perhaps under the influence of Emeritus Pope Benedict?) set forth the chief reasons a dialogue between Christianity and secularism is needed. First, because the “light” of Christianity has come to be seen as “darkness.” The Pope writes: “In the centuries of modern life, we have seen a paradox: Christian faith, whose novelty and importance in the life of mankind since the beginning have been expressed through the symbol of light, has often been branded as the darkness of superstition which is opposed to the light of reason. Therefore a lack of communication has arisen between the Church and the culture inspired by Christianity on one hand, and the modern culture of Enlightenment on the other. The time has come and the Second Vatican Council has inaugurated the season for an open dialogue without preconceptions that opens the door to a serious and fruitful meeting.”

The second reason, the Pope says, is that dialogue is not secondary to Christian faith but central to it. Francis writes: “The second circumstance, for those who attempt to be faithful to the gift of following Jesus in the light of faith, derives from the fact that this dialogue is not a secondary accessory in the existence of those who believe, but is rather an intimate and indispensable expression. Speaking of which, allow me to quote a very important statement, in my opinion, of the encyclical: as the truth witnessed by faith is found in love — it is stressed — ‘it seems clear that faith is not unyielding, but increases in the coexistence which respects the other. The believer is not arrogant; on the contrary, the truth makes him humble, in the knowledge that, rather than making us rigid, it embraces us and possesses us. Rather than make us rigid, the security of faith makes it possible to speak with everyone’ (n. 34). This is the spirit of the words I am writing to you.”

And then Francis, in his letter to Scalfari, sets forth his own faith — a faith that had an element of mystical experience, and yet also a faith which depended profoundly on the mediation of the “community of faith” into which he was born: the Church.

“For me, faith began by meeting Jesus,” Francis wrote. “A personal meeting that touched my heart and gave a direction and a new meaning to my existence. At the same time, however, a meeting that was made possible by the community of faith in which I lived and thanks to which I found access to the intelligence of the Sacred Scriptures, to the new life that comes from Jesus like gushing water through the sacraments, to fraternity with everyone and to service to the poor, which is the real image of the Lord. Believe me, without the Church I would never have been able to meet Jesus, in spite of the knowledge that the immense gift of faith is kept in the fragile clay vases of our humanity.”

And from this “rootedness” in both personal (mystical) experience and the rich faith life of the Church, Francis was ready to propose to Scalfari a common journey: “Now, thanks to this personal experience of faith experienced in the Church, I feel comfortable in listening to your questions and together with you, will try to find a way to perhaps walk along a path together.”

The letter then proceeds at some length, and Francis sets forth in powerful arguments the reasons for his faith in Jesus. There is not space here to follow the entire argument, but it is worth summarizing some of the main points.

Francis (again, perhaps under the influence, in part, of Emeritus Pope Benedict) urges Scalfari to go back to the Gospels, which he characterizes as accurate historical records of what happened during the life of Jesus. He particularly encourages reading the Gospel of Mark, which is, he says, “the most ancient of the Gospels.”

Francis writes: “Therefore, I would say that we must face Jesus in the concrete roughness of his story, as above all told to us by the most ancient of the Gospels, the one according to Mark. We then find that the ‘scandal’ which the word and practices of Jesus provoke around him derive from his extraordinary ‘authority’: a word that has been certified since the Gospel according to Mark, but that is not easy to translate well into Italian. The Greek word is ‘exousia,’ which literally means ‘comes from being’ what one is. It is not something exterior or forced, but rather something that emanates from the inside and imposes itself. Actually Jesus amazes and innovates starting from (he himself says this) his relationship with God, called familiarly Abbà, who gives him this ‘authority’ so that he uses it in favor of men.”

Francis continues: “So Jesus preaches ‘like someone who has authority’; he heals, calls his disciples to follow him, forgives… things that, in the Old Testament, belong to God and only God. The question that is most frequently repeated in the Gospel according to Mark: ‘Who is he who…?,’ and which regards the identity of Jesus, arises from the recognition of an authority that differs from that of the world, an authority that aims not at exercising power over others, but rather serving them, giving them freedom and the fullness of life. And this is done to the point of staking his own life, up to experiencing misunderstanding, betrayal, refusal, until he is condemned to die, left abandoned on the cross. But Jesus remained faithful to God up to his death.”

Francis concludes: “And it is then — as the Roman centurion exclaims, in the Gospel according to Mark — that Jesus is paradoxically revealed as the Son of God. Son of a God who is love and who wants, with all of himself, that man, every man, discover himself and also live like his real son. For Christian faith this is certified by the fact that Jesus rose from the dead: not to be triumphant over those who refused him, but to certify that the love of God is stronger than death, the forgiveness of God is stronger than any sin and that it is worthwhile to give one’s life, to the end, to witness this great gift.

“Christian faith believes in this: that Jesus is the Son of God who came to give his life to open the way to love for everyone. Therefore there is a reason, dear Dr. Scalfari, when you see the incarnation of the Son of God as the pivot of Christian faith. Tertullian wrote ‘caro cardo salutis,’ the flesh (of Christ) is the pivot of salvation. Because the incarnation, that is, the fact that the Son of God has come into our flesh and has shared the joy and pain, the victories and defeat of our existence, up to the cry of the cross, living each event with love and in the faith of Abbà, shows the incredible love that God has for every man, the priceless value that he acknowledges. For this reason, each of us is called to accept the view and the choice of love made by Jesus, become a part of his way of being, thinking and acting. This is faith, with all the expressions that have been dutifully described in the encyclical… [Note: here follow several other paragraphs, reflecting also on the role of the Jews in salvation history, and on other important matters.]

“Dear Dr. Scalfari, here I end these reflections of mine, prompted by what you wanted to tell and ask me. Please accept this as a tentative and temporary reply, but sincere and hopeful, together with the invitation that I made to walk a part of the path together. Believe me, in spite of its slowness, the infidelity, the mistakes and the sins that may have and may still be committed by those who compose the Church, it has no other sense and aim if not to live and witness Jesus: He has been sent by Abbà ‘to bring good news to the poor… to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor’ (Luke 4: 18-19).

With brotherly love,

Francesco”

So ended the September 11 letter.

Now there is a fascinating “postscript,” or continuation, to this remarkable letter.

Pope Francis, after writing to Scalfari, decided out of the blue to call him on the telephone. Pope Francis asked Scalfari if he would like to come to the Domus Santa Marta and talk to him personally. And Scalfari agreed.

The two met on September 24, and out of this encounter came one of the most remarkable — and controversial — interviews in many years.

That interview was published on October 1, and it caused a sensation, most of all because some of the phrases used by the Pope in his private conversation with Scalfari seemed scandalous to more tractional Catholics, especially a remark about proselytism being “pious nonsense.” But all of the Pope’s words must be understood in context, and that context was a conversation with a very intelligent, very influential Italian atheist with whom the Pope hoped to begin a dialogue. The Pope did not want to invite Scalfari to his home in order to “proselytize” him, in the sense of imposing from without a faith that Scalfari did not have, but might be seeking. Rather, he hoped to initiate a dialogue with a man who was far from the faith, but nevertheless, willing to discuss the reasons for that distance. If one reads the interview, one can see that the Pope was engaging with Scalfari on a profound level. And that suggests that what was occurring — the conversation between a Pope and the man who is one of Italy’s most clever and influential atheists — was remarkable, and the work of the Holy Spirit.

Here below are excerpts from the Scalfari-Francis conversation. (It was later revealed that Scalfari did not use a tape recorder, but reconstructed the conversation from memory. The Vatican later stated that, nevertheless, the printed version of the conversation did correspond essentially to what the Pope had said. However, it is clear that there is no certainty that the Pope spoke exactly the words that Scalfari has printed as his words, though the essential meaning is accurate.)

“The meeting with Pope Francis took place last Tuesday [Note: September 24] at his home in Santa Marta, in a small bare room with a table and five or six chairs and a painting on the wall,” Scalfari began. “It had been preceded by a phone call I will never forget as long as I live.

“It was half past two in the afternoon. My phone rings and in a somewhat shaky voice my secretary tells me: ‘I have the Pope on the line. I’ll put him through immediately.’

“I was still stunned when I heard the voice of His Holiness on the other end of the line saying, ‘Hello, this is Pope Francis.’ ‘Hello, Your Holiness,’ I say, and then, ‘I am shocked. I did not expect you to call me.’ ‘Why so surprised? You wrote me a letter asking to meet me in person. I had the same wish, so I’m calling to fix an appointment. Let me look at my planner: I can’t do Wednesday, nor Monday; would Tuesday suit you?’ I answer, that’s fine. ‘The time is a little awkward, three in the afternoon, is that okay? Otherwise it’ll have to be another day.’ ‘Your Holiness, the time is fine.’ ‘So we agree: Tuesday the 24th at 3 o’clock. At Santa Marta. You have to come in through the gate at the Sant’Uffizio.’

“I don’t know how to end this call and I let myself go, saying: ‘Can I embrace you by phone?’ ‘Of course, a hug from me too. Then we will do it in person. Goodbye.’”

So the meeting was set. Scalfari agreed to come to meet Pope Francis, the head of a Church and a faith Scalfari had spent much of his adult life criticizing, attacking, mocking, undermining. The very fact that the two would meet is extraordinary. But it happened.

Scalfari writes: “And here I am. The Pope comes in and shakes my hand, and we sit down. The Pope smiles and says: ‘Some of my colleagues who know you told me that you will try to convert me.’”

[Note: And so we see here that the first mention of the word “convert,” that is, the first mention of a desire to proselytize, is made by Pope Francis, who says that his friends had joked that Scalfari would try to proselytize him to accept atheism.]

“It’s a joke, I tell him. My friends think it is you who want to convert me.”

[Note: And so we see that these two men are telling each other that both of them have friends who have warned them that the other will try to persuade them to reject their own beliefs and to accept the beliefs of the other. And it is in this very precise context, in order to “break the ice” and to lay the basis for a conversation which is authentic — and therefore which could, in fact, lead one or the other to change his beliefs — that the Pope made his controversial remarks about proselytism.]

Scalfari continues: “He smiles again and replies: ‘Proselytism is solemn nonsense; it makes no sense. We need to get to know each other, listen to each other and improve our knowledge of the world around us. Sometimes after a meeting I want to arrange another one because new ideas are born and I discover new needs. This is important: to get to know people, listen, expand the circle of ideas. The world is crisscrossed by roads that come closer together and move apart, but the important thing is that they lead towards the Good.’”

The Pope then made some remarks in defense of individual conscience — “Everyone has his own idea of good and evil and must choose to follow the good and fight evil as he conceives them,” — and then asked Scalfari, “Do you know what agape is?” [Note: Agape is the Greek word for disinterested love, brotherly love.]

“Yes, I know,” Scalfari said.

“It is love of others, as our Lord preached,” Francis said. “It is not proselytizing, it is love. Love for one’s neighbor, that leavening that serves the common good.”

“Love your neighbor as yourself,” Scalfari said.

“Exactly so,” Francis said. “The Son of God became incarnate in order to instill the feeling of brotherhood in the souls of men. All are brothers and all children of God, Abbà, as he called the Father. I will show you the way, he said. Follow me and you will find the Father, and you will all be his children and he will take delight in you. Agape, the love of each one of us for the other, from the closest to the furthest, is in fact the only way that Jesus has given us to find the way of salvation and of the Beatitudes.”

As the conversation continued, Francis spoke about the Roman Curia, clericalism, anti-clericalism, liberation theology. The conversation was wide-ranging.

Then the Pope, in answer to a question from Scalfari, gave insight into his state of mind when he was elected Pope on March 13.

“When the conclave elected me Pope, before I accepted, I asked if I could spend a few minutes in the room next to the one with the balcony overlooking the square,” Francis said. “My head was completely empty and I was seized by a great anxiety.” [Note: This is one of the answers which is cited by observers as evidence that Scalfari did not present his interview with the Pope, which of course did occur, in a completely accurate way. There is no room next to the balcony overlooking St. Peter’s Square. The Pope could not have gone there before accepting the papacy, as he was in the Sistine Chapel, which is far away from the balcony, several hundred yards. So this is not accurate. The Pope must have said he went to a little room next to the Sistine Chapel. Again, this does not mean that Scalfari has misrepresented the essential meaning of the Pope, only that this interview is imperfect, it is not a word-for-word translation of what the Pope said.]

“To make it go way and relax, I closed my eyes and made every thought disappear, even the thought of refusing to accept the position, as the liturgical procedure allows.

“I closed my eyes and I no longer had any anxiety or emotion. At a certain point I was filled with a great light. It lasted a moment, but to me it seemed very long.

“Then the light faded. I got up suddenly and walked into the room where the cardinals were waiting and the table on which was the act of acceptance. I signed it, the Cardinal Camerlengo countersigned it, and then on the balcony there was the Habemus Papam.”

In this admission of a type of mystical experience in the moments after his election as Pope, but before his acceptance of the office, Francis is revealing something intimate and profound. He is revealing his own sense of weakness and unworthiness, and yet also, his sense that the Holy Spirit is sustaining and guiding him. He makes reference to this dynamic in the answers which follow below.

Scalfari continues: “We were silent for a moment; then I said: ‘We were talking about the saints that you feel closest to your soul and we were left with Augustine. Will you tell me why you feel very close to him?’”

Francis replied: “Even for my predecessor, Augustine is a reference point. That saint went through many vicissitudes in his life and changed his doctrinal position several times. He also had harsh words for the Jews, which I never shared. He wrote many books and what I think is most revealing of his intellectual and spiritual intimacy are the Confessions, which also contain some manifestations of mysticism, but he is not, as many would argue, a continuation of Paul. Indeed, he sees the Church and the faith in very different ways than Paul. Perhaps four centuries passed between one and the other.”

We note in these remarks the fascination of Francis for St. Paul. Paul was converted from a persecutor of Christians and became the last and most energetic of the Apostles after his experience on the road to Damascus. Paul also established churches throughout the Mediterranean world, and began to codify many Church procedures and structures. But Francis is also fascinated by Augustine, who also had a mystical conversion to the faith, and who functioned as a theologian and bishop in an age when Christianity was socially accepted, but when the entire Roman Empire and culture were in decline.

In his reflection on conversion, on the grace of conversion, Francis gives us a deep insight into his own theology of conversion. This helps us understand why he is speaking and acting as he is.

Scalfari asks: “What is the difference (i.e., between Paul and Augustine), Your Holiness?”

Francis replies: “For me it lies in two substantial aspects. Augustine feels powerless in the face of the immensity of God and the tasks that a Christian and a bishop have to fulfill. In fact, he was by no means powerless, but he felt that his soul was always less than he wanted and needed it to be. And then the grace dispensed by the Lord as a basic element of faith. Of life. Of the meaning of life. Someone who is not touched by grace may be a person without blemish and without fear, as they say, but he will never be like a person who has touched grace. This is Augustine’s insight.”

And then follows a remarkable exchange on grace, the energy or life of God, the holiness of God, which touches and influences and heals souls. This is not all theologically crafted — it is an informal interview, and one not recorded, so, unreliable in its verbal formulations — but it gives us a fascinating insight into Francis’s view of grace.

Scalfari asks: “Do you feel touched by grace?”

Francis replies: “No one can know that. Grace is not part of consciousness, it is the amount of light in our souls, not knowledge or reason. Even you, without knowing it, could be touched by grace.”

“Without faith? A non-believer?” Scalfari asks.

Francis replies: “Grace regards the soul.”

“I do not believe in the soul,” Scalfari says.

“You do not believe in it, but you have one,” says Francis.

“Your Holiness, you said that you have no intention of trying to convert me and I do not think you would succeed,” Scalfari says.

“We cannot know that, but I don’t have any such intention,” Francis replies.

So in these lines we see the idea of conversion, proselytism, emerging again. One senses that, in this conversation, these two men, one a leading atheist, the other the leader of the Church, were circling each other, trying to gauge the reliability, the honesty, the openness, of the other. Humanly speaking, it is a riveting drama.

Scalfari then asks the Pope what he thinks of St. Francis of Assisi, the saint whose name he chose as his own as Pope.

“And St. Francis?” Scalfari asks.

“He’s great because he is everything,” Francis replies. “He is a man who wants to do things, wants to build; he founded an order and its rules, he is an itinerant and a missionary, a poet and a prophet; he is mystical. He found evil in himself and rooted it out. He loved nature, animals, the blade of grass on the lawn and the birds flying in the sky. But above all he loved people, children, old people, women. He is the most shining example of that agape we talked about earlier.”

“Your Holiness is right,” Scalfari replies, “the description is perfect. But why did none of your predecessors ever choose that name? And I believe that after you no one else will choose it.”

“We do not know that,” Francis replies. “Let’s not speculate about the future. True, no one chose it before me. Here we face the problem of problems. [Note: The Pope will address this “problem of problems” in the lines below.] Would you like something to drink?”

“Thank you, maybe a glass of water,” Scalfari says.

Scalfari writes: “He gets up, opens the door and asks someone in the entrance to bring two glasses of water. He asks me if I want a coffee. I say no. The water arrives. At the end of our conversation, my glass will be empty, but his will remain full. He clears his throat and begins.”

And then Francis explains Francis — Pope Francis explains St. Francis.

“Francis wanted a mendicant order and an itinerant one,” Pope Francis told Scalfari. “Missionaries who wanted to meet, listen, talk, help, to spread faith and love. Especially love. And he dreamed of a poor Church that would take care of others, receive material aid and use it to support others, with no concern for itself. Eight hundred years have passed since then, and times have changed, but the ideal of a missionary, poor Church is still more than valid. This is still the Church that Jesus and his disciples preached about.”

One senses in these words the tension between the ideal and the real, the Church as saints like Francis, and men like Pope Francis, long for it to be, and the Church as it actually is, not missionary, not poor, not concerned only for others, but concerned in part for itself, its property and privileges.

Scalfari then asks about the Church’s prospects in a world where Christians were once culturally dominant.

“You Christians are now a minority,” Scalfari says. “Even in Italy, which is known as the Pope’s backyard. Practicing Catholics, according to some polls, are between 8 and 15 percent… In the world, there are a billion Catholics or more, and with other Christian Churches there are over a billion and a half, but the population of the planet is 6 or 7 billion people. There are certainly many of you, especially in Africa and Latin America, but you are a minority…”

Francis replies: “We always have been, but the issue today is not that. Personally, I think that being a minority is actually a strength. We have to be a leavening of life and love and the leavening is infinitely smaller than the mass of fruits, flowers and trees that are born out of it. I believe I have already said that our goal is not to proselytize but to listen to needs, desires and disappointments, despair, hope. We must restore hope to young people, help the old, be open to the future, spread love. Be poor among the poor. We need to include the excluded and preach peace. Vatican II, inspired by Pope Paul VI and John, decided to look to the future with a modern spirit and to be open to modern culture. The Council Fathers knew that being open to modern culture meant religious ecumenism and dialogue with non-believers. But afterwards very little was done in that direction. I have the humility and ambition to want to do something.”

Scalfari then acknowledges the crisis that secular culture now faces.

“Modern society throughout the world is going through a period of deep crisis,” Scalfari says, “not only economic but also social and spiritual. Even we non-believers feel this. That is why we want dialogue with believers and those who best represent them.”

This is a fascinating admission from a leading atheist, and it echoes something a leading cardinal once told Inside the Vatican: that the secular elites, when they realize the abyss which looms before them in the spiritual misery of the de-Christianized world they have created, will turn again to the Church for help, guidance, insight, to build a better, more harmonious, less unjust and less cruel society, and that the Church must prepare, in these difficult years, for that moment.

“I don’t know if I’m the best of those who represent believers, but Providence has placed me at the head of the Church and the Diocese of Peter,” Francis said. “I will do what I can to fulfill the mandate that has been entrusted to me.”

Francis then agreed with Scalfari that “love for temporal power is still very strong within Vatican walls and in the institutional structure of the whole Church.” And he added: “Even Francis in his time held long negotiations with the Roman hierarchy and the Pope to have the rules of his order recognized. Eventually he got the approval but with profound changes and compromises.”

Scalfari, a bit mischievously, asks: “Will you have to follow the same path?”

And Pope Francis replies: “I’m not Francis of Assisi and I do not have his strength and his holiness. But I am the Bishop of Rome and Pope of the Catholic world. The first thing I decided was to appoint a group of eight cardinals to be my advisers. Not courtiers, but wise people who share my own feelings. This is the beginning of a Church with an organization that is not just top-down but also horizontal. When Cardinal Martini talked about focusing on the Councils and Synods, he knew how long and difficult it would be to go in that direction. Gently, but firmly and tenaciously.”

As the interview is nearing its end, Francis turns the tables a bit. He asks Scalfari: “But now let me ask you a question: you, a secular non-believer in God, what do you believe in? You are a writer and a man of thought. You believe in something, you must have a dominant value… I am asking what you think is the essence of the world, indeed the universe. You must ask yourself, of course, like everyone else, who we are, where we come from, where we are going. Even children ask themselves these questions. And you?”

“I believe in Being, that is, in the substance from which forms, bodies arise,” Scalfari says.

“And I believe in God,” Francis replies, “not in a Catholic God, there is no Catholic God, there is God, and I believe in Jesus Christ, his incarnation. Jesus is my teacher and my pastor, but God, the Father, Abbà, is the light and the Creator. This is my Being. Do you think we are very far apart?”

Scalfari replies: “Your Holiness, you are certainly a person of great faith, touched by grace, animated by the desire to revive a pastoral, missionary Church that is renewed and not temporal. But from the way you talk and from what I understand, you are and will be a revolutionary Pope. Half Jesuit, half a man of Francis, a combination that perhaps has never been seen before.”

Scalfari writes: “We embrace. We climb the short staircase to the door… We shake hands and he stands with his two fingers raised in a blessing. I wave to him from the window. This is Pope Francis. If the Church becomes like him and becomes what he wants it to be, it will be an epochal change.”

(The text of the interview was translated from Italian to English by Kathryn Wallace. Reporting by Marinella Bandini, an Italian journalist who lives and works in Rome.)

Facebook Comments