By William Doino Jr

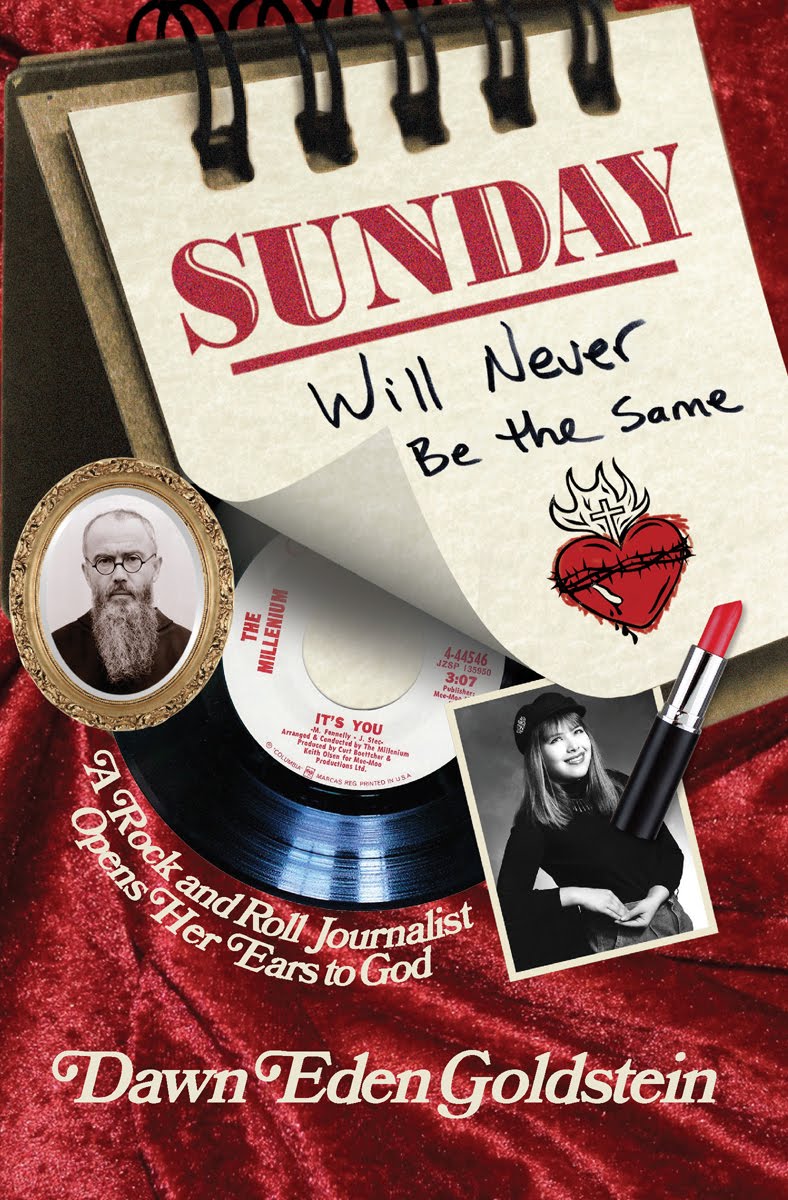

Of all the modern conversions to the Roman Catholic Church, few, if any, compare with Dawn Eden Goldstein’s. A former rock critic turned theologian, she has now written a memoir, Sunday Will Never be the Same: A Rock and Roll Journalist Opens Her Ears to God.

Dawn Eden Goldstein (pictured above), is the author of The Thrill of the Chaste and My Peace I Give You: Healing Sexual Wounds with the Help of the Saints, among other works. Together, Dawn’s books have sold more than 40,000 copies worldwide, including translations into Spanish, Polish, Italian, Slovak, and Chinese.

As an affectionate nod to her former profession, Goldstein’s title is taken from a hit song, as are the titles of each one of her memoir’s chapters. But as the reader soon learns, these songs (“I Go to Pieces,” “Little Bit O’Soul,” “Homeward Bound,” “Along Comes Mary”) take on new meanings, in light of her spiritual development.

Goldstein is the author of several acclaimed works on chastity, sexual wounds, and Divine Mercy, but Sunday may be her best book yet: a fascinating, humorous, moving—and often searing—account of her unexpected journey into Catholicism.

Written in the present tense, as a series of life-changing events and personal reflections—each marked by the year, day and time—Dawn aims to place the reader in her mind and heart, just as she was experiencing them.

In structuring her memoir this way, Goldstein took a risk, as the book easily could have become disjointed and difficult to follow. But because she writes so well—and seamlessly connects one pivotal event with another, even those separated by years –Sunday Will Never be the Same excels. With its vivid, cinema-like narrative, it captivates readers from the start, and never lets the momentum slow.

Born in 1968, Goldstein was raised in a Reformed Jewish household, and had an almost idyllic childhood, growing up in Galveston, Texas. Living in a state of innocence, she day-dreamed often, was at peace with God, and believed love could conquer the world.

That all changed, however, after two shattering events: the divorce of her parents, and her sexual abuse by a local janitor. Although her mother tried valiantly to get the abuser punished (unsuccessfully, alas, as it was his word against a five-year-old’s), Dawn felt her mom, as loving as she was, never quite understood the trauma she experienced, creating an emotional rift between the two. When Goldstein was abused again, just a short time later, her relations with everyone worsened, as she withdrew into acute depression and misplaced guilt.

Scarred from an early age, Goldstein nevertheless tried to maintain her equilibrium during high school and college. To their credit, her family and friends did everything they could to help. But by then, Dawn was suffering from an (undiagnosed) form of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, haunted by constant thoughts of suicide. Flashbacks of her abuse, combined with an overriding sense that God had abandoned her, increased with each agonizing day.

One way she coped was by immersing herself in popular rock music– particularly from the post-Camelot but pre-Woodstock Sixties– which she fell in love with. Popular rock, in fact, became the one source of stability in Dawn’s life, and brought forth unexpected graces: it reawakened her longing for transcendence, indirectly led to her conversion, and very likely saved her life.

That may come as a shock to those who believe rock is nothing but subversive, aimed at creating chaos and unleashing disordered sexual passions. But Goldstein’s story and her love of high-quality music challenge those assumptions, rescuing rock from those who would universally condemn it.

Here, she makes a valuable cultural point.

Anyone unable to appreciate the astonishingly introspective rock classics, “Walk Away Renee,” and “Care of Cell 44” –the first about loving a person so much that one place’s his or her well-being above one’s own; the second about expressing hope for a tomorrow that may never come—is shortchanging their achievement. Similarly, listeners left unmoved by the powerful Christian overtones of David Bowie’s “Word on a Wing” and Warren Zevon’s “Desperados Under the Eaves,” both about overcoming addiction and despair, is missing out on something special.

Goldstein is able to perceive, in the best of rock, what its detractors cannot: its intricate craft, its lyricism, and its call to a higher, more fulfilling life.

None of which is to deny that many criticisms of popular rock (not to mention heavy metal and rap), are entirely justified. There has always been a dark side to rock and roll culture, and no one is more aware of it than Goldstein: she has witnessed it, written about it, and been personally burned by it, as her candid memoir reveals. Yet, for all its temptations, popular rock contains many avenues of light, and Goldstein was just fortunate enough to find them.

Despite her cyclical depression, Goldstein’s passion for music and talent as a writer enabled her to become one of the leading rock historians of her generation. After settling in New York in the 1980s and 90s, she interviewed rock icons like Del Shannon, Brian Wilson, Dave Davies and Harry Nilsson, and made it a point to discover new talent in little-known hideaways and clubs. Celebrating overlooked and underrated musicians, in fact, became one of Dawn’s abiding passions; and one artist, in particular, took her by storm: Curt Boettcher.

Boettcher is known today by a modest base of fervent admirers who consider him a musical genius-and not without reason. He dazzled the Beach Boys, produced hits for other Sixties pop stars, and was the lead vocalist on two of the decade’s most extraordinary (if commercially unsuccessful) albums, Present Tense and Begin. Boettcher sang incandescent ballads, like “It’s You,” and “Another Time,” which were laden with sadness but also contained elements of hope—much like Goldstein’s fluctuating emotions. When Dawn first heard them, she was “utterly transported.” The songs lifted her like no others, and she identified with Boettcher’s palpable search for something deeper, “reaching out toward a love of seemingly cosmic dimensions.” Her desire for transcendence returned, albeit in a tentative, incremental way.

Given a new purpose, she set out to discover everything she could about Boettcher, and finally give his music the attention it deserved. But after several promising leads, she discovered that Boettcher had died just months before she planned to interview him. Goldstein was crushed. Although she continued to write about him, and succeeded at sparking a mini-revival of his music (which continues to this day), Dawn’s inability to personally reach Boettcher before his death weighed upon her. So, too, did the premature, tragic deaths of Shannon and Nilsson, two other storied musicians she felt a close connection to.

By 1995, Goldstein was again trapped in “an emotional black hole”—and in a race against time and herself. The only question became whether she would find a new passion project to take her mind away from self-destructive thoughts– or end her own life first.

Dawn was desperate and in need of a real miracle. Without realizing it, she received one.

In 1995, during a phone interview with Ben Eshbach, an alternative rock musician from Los Angeles, Goldstein asked him what he had been reading lately. “G. K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday,” he replied. Goldstein had never heard of Chesterton, much less his metaphysical thriller, but she made a note to read it, so she’d have something to discuss with Eshbach when his band visited New York. A short time later, she picked up a copy– and hasn’t been the same since.

Intrigued by Chesterton’s vibrant vision of life—above all his belief in the superiority of order and beauty over rebellion and anarchy—she saw a new path opening up for her. The protagonist of The Man Who was Thursday, arguing about the nature of poetry against an anarchist, captured her changing outlook: “It is things going right,” he proclaims, that are truly poetical: “Yes, the most poetical thing, more poetical than the flowers, more poetical than the stars—the most poetical thing in the world is not being sick.”

Those last lines affected Dawn deeply, especially as they related to her own situation. She kept repeating them in her mind, dreaming what it would be like to feel right again.

Never one for half measures, Goldstein studied everything she could about Chesterton, just as she had with Boettcher. And what she found in Chesterton was all the transcendence Boettcher gave her, but this time with a distinctly Christian purpose.

She began to study the Bible and pray– first for small things, then for larger ones, and to her surprise, found her most important prayers being answered. This led to a deeper exploration of Christianity and ultimately to a profound mystical experience, as beautifully rendered as it is convincing.

From that moment forward, Dawn embraced Christ and was freed from her debilitating depression—though not, as she astutely notes, from the requirements of being His disciple. Becoming a Christian (in her case, an Evangelical first) meant far more than just professing Christ; it meant turning away from the hook-up culture she had become involved with, because of her depression and intense loneliness. It also meant vigorously defending the Gospel on all fronts, a challenging task for any young Christian in the modern world. But she managed to survive and even flourish—until she faced her first major post-conversion crisis.

Having become a copy editor at the New York Post, Goldstein was asked to review a story about in-vitro fertilization. But when she saw that it was suppressing the fact that “spare” embryos are routinely killed in the process, she inserted language making that clear. Though her changes were morally and scientifically correct, she didn’t secure approval from her superiors first, as she should have. When the secretly revised story appeared in the Post’s published edition, it created an uproar. Even though Goldstein immediately apologized and tried to make amends, her outspoken pro-life convictions eventually led to her firing, with the Post’s editor pointing an accusing finger at her, thundering, “You are a liability!”

The Post’s loss was the Catholic Church’s gain, however; for this dismissal only accelerated Goldstein’s road to Rome.

During her ordeal at the Post, waiting for the proverbial axe to fall, Goldstein realized she needed a friend—and not just any kind of friend, but a supernatural one. So, she began asking St. Maximilian Kolbe—the patron saint of journalists and pro-lifers—to intercede for her before the Lord. Although she was still an Evangelical at the time, and harbored reservations about certain Catholic teachings, including intercessory prayer, she experienced an unknown serenity after praying to Kolbe, reflecting what Romano Guardini wrote about the saints:

“They open up the riches of Christ. Whereas He is ‘the Light,’ simple and at the same time all-embracing, the saints break up this mysterious brilliance like a prism breaking up the white light in the spectrum, allowing first one color to shine and then another. They can help the believer to understand himself in this light of Christ and to discover the road which leads to Him.”

Dawn was equally moved by St. Maximilian’s martyrdom at Auschwitz, where he gave his life to save another prisoner; and by Kolbe’s stirring words which led to his arrest by the Nazis:

“No one in the world can change Truth. What we can do and should do is seek truth and serve it when we have found it. The real conflict is the inner conflict. Beyond armies of occupation and the hecatombs of extermination camps, there are two irreconcilable enemies in the depth of every soul: good and evil, sin and love. And what use are the victories on the battlefield if we ourselves are defeated in our innermost personal selves?”

The last several chapters of Sunday Will Never be the Same take on an unusual power, as Goldstein describes her entry into the Catholic Church, and how that decision changed her life forever.

The day after her conversion, during Holy Week in 2006, Dawn received her first Communion and knew there was “something different now, something new, something I needed.”

Soon thereafter, Dawn participated in the annual Way of the Cross procession through downtown Manhattan, recognizing a dramatic gulf between the sacred and profane—but also the urgent need for Christians to evangelize the culture.

As the procession passed by Planned Parenthood’s headquarters and “posters for Madonna’s latest tour,” the group began to pray, praise God in Latin, and sing the “Ave Maria,” alongside hangouts where men and women caroused the night away.

Though she was saddened thinking about all those living apart from God, she now felt a part of a new community which was actively doing something to address it:

“As the procession winds its way through the Village, our songs echoing through the darkened streets, I have the feeling that we are bringing salt and light….

“A mental image comes to me, the same one I had last night when I had my First Communion. It’s an image of the globe of the Earth. I see it being sheathed in darkness, but every so often a patch of light breaks through. The picture brings to mind patches of new, healed skin emerging on a leper—and the healing keeps leading to more healing.”

Suddenly, Dawn then experienced a surge of spiritual strength:

“It feels so radical to take back the streets with song and prayer. We aren’t blocking anyone, we aren’t accosting anyone. All we are doing is being a living witness to Jesus’ love and lordship.

“I am so thankful to be part of a Church that witnesses so boldly, peacefully, and powerfully. I want to pray outside abortion clinics now. I want to make processions everywhere.”

The memoir also introduces us to two exemplary religious, who, though no longer living, have had a lasting impact upon Dawn—Father Francis Canavan, the legendary Jesuit who taught at Fordham University; and Sr. Geraldine Calabrese, an extraordinary nun who, though blind and stricken with cancer, radiated joy toward everyone she met. It was Father Canavan who played a decisive role in persuading Goldstein to pursue her doctorate in Catholic theology, since, as he told her, “Faithful Catholic colleges need faithful Catholic professors.” And it was Sr. Gerry who encouraged Dawn to draw close to the Blessed Virgin Mary, enabling Dawn to fully reconcile with her mom, after years of tension and misunderstanding, in one of the book’s high points.

The gratitude Dawn expresses for these blessings—and for all the graces the Church has given her– is overwhelming.

Reading Sunday Will Never be the Same, I could not help but be reminded of another Catholic convert—Edith Stein, the great Carmelite nun and martyr, now known as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. While there are obvious historical and cultural differences between Goldstein and Stein, there are also striking parallels: both were raised Jewish; both drifted away from faith as teenagers and became agnostic; both went through severe bouts of depression; both overcame their despair by discovering truth and hope in the Catholic Church; both received doctoral degrees, as women, in male-dominated disciplines; both eagerly shared their new Catholic faith; and after their conversions, expressed a renewed appreciation for their Jewish heritage, emphasizing Judaism’s unique and indispensable role within Christianity.

These days, when she is not writing, lecturing and teaching, Dawn can be found far more often at Catholic cathedrals and basilicas than rock concerts, though her love for great music remains.

At a time when we read so much about young “nones” and their disenchantment with organized religion—and when our national suicide rate has reached tragic new heights—it is inspiring to read a memoir like this one, which not only explains why Catholicism can heal and transform, but–to quote the soon-to-be beautified Fulton J. Sheen—reveals why life is so worth living.

Facebook Comments