In Psalm 51, King David sought God’s forgiveness, in lines that were woven into the prayers of the old Mass:

Psalm 51:1-19

For the director of music. A psalm of David. When the prophet Nathan came to him after David had committed adultery with Bathsheba.

1 Have mercy on me, O God,

according to your unfailing love;

according to your great compassion

blot out my transgressions.

2 Wash away all my iniquity

and cleanse me from my sin.

3 For I know my transgressions,

and my sin is always before me.

(…)

7 Cleanse me with hyssop, and I will be clean;

wash me, and I will be whiter than snow.

(…)

10 Create in me a pure heart, O God,

and renew a steadfast spirit within me.

11 Do not cast me from your presence

or take your Holy Spirit from me.

12 Restore to me the joy of your salvation

and grant me a willing spirit, to sustain me.

13 Then I will teach transgressors your ways,

and sinners will turn back to you.

14 Save me from bloodguilt, O God,

the God who saves me,

and my tongue will sing of your righteousness.

15 O Lord, open my lips,

and my mouth will declare your praise.

16 You do not delight in sacrifice, or I would bring it;

you do not take pleasure in burnt offerings.

17 The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.

(…)

The image above is a detail of “David’s Punishment” by Julius Schnoor von Carolsfeld (German artist, 1794-1872), woodcut illustration in Das Buch der Bücher in Bilden (“The Book of Books in Pictures”)

Letter #19, 2025, Saturday, February 1: Motu Proprio, Pt 7

I want to again introduce this serial presentation of a lecture I gave almost 18 years ago, in the summer of 2007.

On August 17, 2007, I gave a talk at a church in California, St. Cecilia Church in Tustin, near Los Angeles, on the decision of Pope Benedict XVI to issue on July 7, 2007, his motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, granting wider use of the old liturgy throughout the world.

The motu proprio had been published just 5 weeks before.

So, at that time, in August 2007, it was entirely in keeping with the wishes of Rome, and of the Pope, to receive and to accept and to praise and to embrace that document.

Pope Benedict had encouraged me to try to explain his intent in the pages of my magazine, Inside the Vatican, and in any talks I gave.

So I felt “authorized” to try to give my interpretation of what he had done, and why, when I gave my first and only talk on the subject, in August 2007.

I spoke without notes, and went on for about an hour. (It was recorded by Terry Barber of St. Joseph Radio — thank you, Terry!)

Even as I gave the talk, I felt it was reasonably effective, but later people told me it was the best talk that I had ever given.

I did speak from my heart, and from my memories as a child, and from my studies as a historian, and from my many conversations with Pope Benedict, in the 1980s and 1990s, when he was still Cardinal Ratzinger.

I tried to be clear, and fair, and reasonable, and faithful, to what I had lived and learned during those decades about the Catholic Mass.

Later, people came up to me and told me that my talk had moved them and instructed them, and they thanked me.

I put the talk onto a CD which was entitled Motu Proprio: Why the Latin Mass? Why Now? (To order a copy, please quick here)

Now, almost 18 years have passed by, and the attitude of Rome, and perhaps also of the Catholic faithful in general, has changed over these nearly two decades. Indeed, in Rome, the current pontiff seems intent on restricting the celebration of the old Mass, for reasons he has set forth in two documents and in several interviews. (see this link from seven months ago).

During December, one month ago, an old friend and reader of the magazine told me that my talk had influenced him deeply, and that he had taken to listening to the talk on his car CD player (I realize that many cars no longer have CD players!) while driving on long trips. “It is a great talk,” he told me. “I may have listened to it 12 times or more by now. I always find something new in it. Why don’t you share it again, make it available again?”

So I decided to publish that talk here, and to make the CD available again. I will also soon be posting a downloadable audio file.

I note again that, when this talk was given, in 2007, it was given in an attempt to explain and defend the reasoning of Pope Benedict, who had acted just 5 weeks before.

The talk was therefore intended to offer my full support to the reigning pontiff, and to explain why he had taken the decision that he took.

—RM

P.S. Order the Motu Proprio: Why the Latin Mass? Why Now? CD here

P.P.S. Subscribe to Inside the Vatican magazine here. (Each subscription is quite helpful to us!)

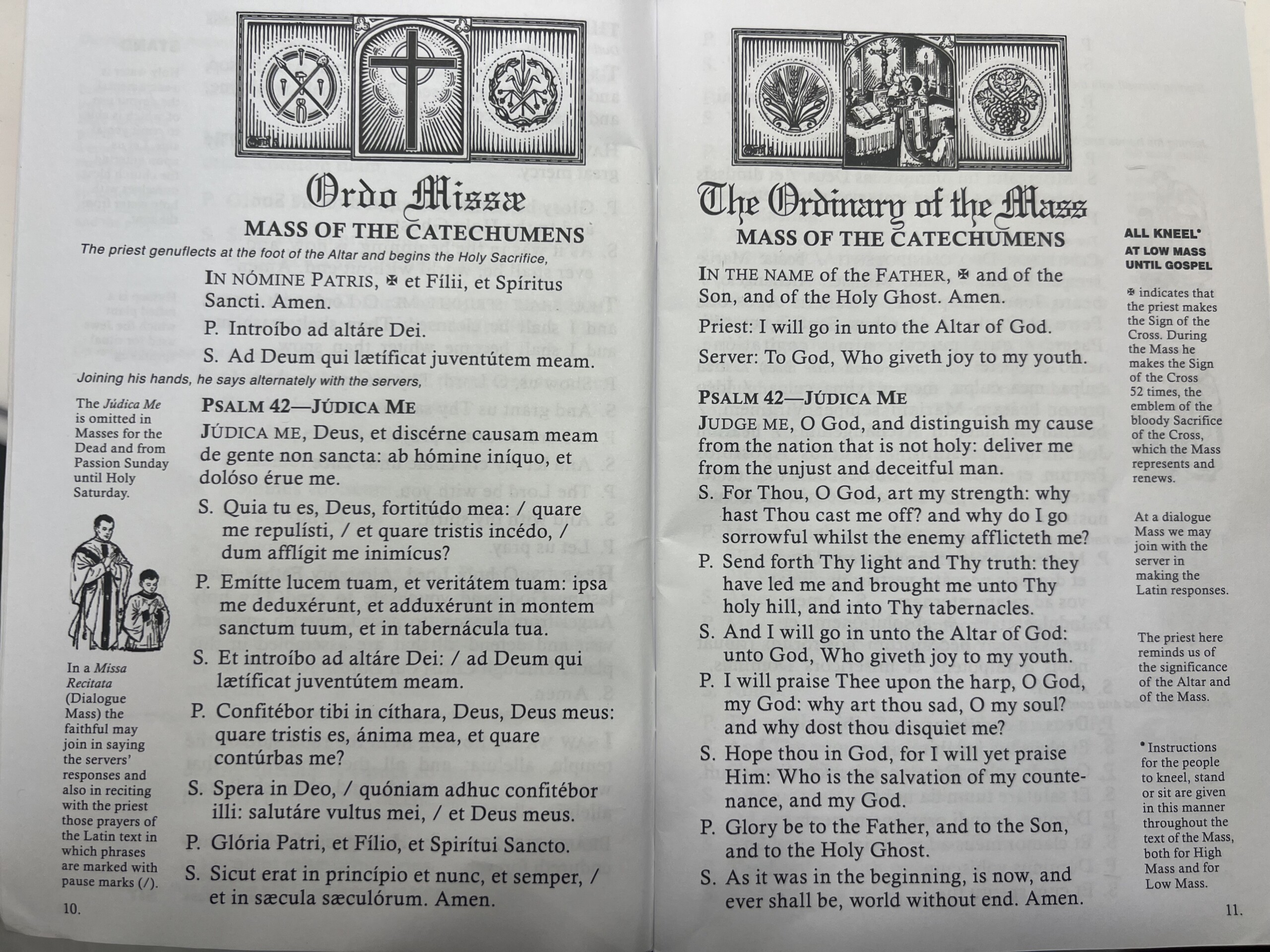

The beginning prayers of the old Mass.

The prayers are drawn from the words of King David in Psalm 42 and Psalm 43.

That Psalm imcludes some of the most beautiful lines found in all of scripture, like “As the hart panteth after the water brooks, so panteth my soul after thee, O God,” expressing the longing, the thirst, of the human for the divine, of man for God:

Psalm 42

42 As the hart panteth after the water brooks, so panteth my soul after thee, O God.

2 My soul thirsteth for God, for the living God: when shall I come and appear before God?

3 My tears have been my meat day and night, while they continually say unto me, Where is thy God?

4 When I remember these things, I pour out my soul in me: for I had gone with the multitude, I went with them to the house of God, with the voice of joy and praise, with a multitude that kept holyday.

5 Why art thou cast down, O my soul? and why art thou disquieted in me? hope thou in God: for I shall yet praise him for the help of his countenance.

6 O my God, my soul is cast down within me: therefore will I remember thee from the land of Jordan, and of the Hermonites, from the hill Mizar.

7 Deep calleth unto deep at the noise of thy waterspouts: all thy waves and thy billows are gone over me.

8 Yet the Lord will command his lovingkindness in the day time, and in the night his song shall be with me, and my prayer unto the God of my life.

9 I will say unto God my rock, Why hast thou forgotten me? why go I mourning because of the oppression of the enemy?

10 As with a sword in my bones, mine enemies reproach me; while they say daily unto me, Where is thy God?

11 Why art thou cast down, O my soul? and why art thou disquieted within me? hope thou in God: for I shall yet praise him, who is the health of my countenance, and my God.

***

Psalm 43

1 Judge me, O God, and distinguish my cause from the nation that is not holy : deliver me from the unjust and deceitful man.

2 For thou art God my strength : why hast thou cast me off? and why do I go sorrowful whilst the enemy afflicteth me?

3 Send forth thy light and thy truth : they have conducted me, and brought me unto thy holy hill, and into thy tabernacles.

4 And I will go in to the altar of God : to God who giveth joy to my youth. [Note: these are the lines of King David’s poetry which began the old Mass.]

5 To thee, O God my God, I will give praise upon the harp : why art thou sad, O my soul? and why dost thou disquiet me? Hope in God, for I will still give praise to him : the salvation of my countenance, and my God.

Motu Proprio: Why the Latin Mass? Why Now?

Part 7

(Continued from previous letter)

We may say “the ship (of the Church in the 1960s) has taken a decisive turn.”

To make this case: that the Second Vatican Council did not bring a “new Church,” did not bring a “new age” Church.

Rather, it brought a reform, a reform which was… badly implemented and still needs to be rightly implemented.

And that is the reform to enable the Christian doctrine and message to be heard by the modern world.

So, Benedict is making “a reform of the reform.”

And the building block, in terms of the liturgy, is this: that the organic development of the old liturgy cannot be despised, cannot be regarded as a negative, “hide-bound,” “narrow-minded,” “right-wing” thing.

No, it’s a beautiful, reverent expression of our fathers and grandfathers for centuries, back to the beginning of worshipping and praising and loving God.

The Old Mass is actually not a Ferrari. It’s not a computer program. It’s not simple. But it’s real.

It’s kind of gnarly, like an old oak tree.

It does have repetitions. And it does use a language which we need to either translate or to study in order to understand it.

And it is a Mass that’s closely linked to the Jewish people.

That’s my first point. The Old Mass is “Hebraic.”

It’s “Hebraic,” first of all.

And, in this context, here is another point that I think is important to remember.

Just like not buying the chairs for the Council (in 1962) because they didn’t think it would last long, the Latin Mass is not “the Latin Mass.”

It’s the Latin, the Greek, and the Aramaic Mass.

It’s the Mass created in the infancy of the Church, codified at Trent in 1570.

But the Aramaic or the Hebrew is in the Old Mass, and it’s still in the New Mass, by the way. “Alleluia” is Aramaic. “Hosanna” is Aramaic. “Amen” is Aramaic. It’s not Latin.

And “Kyrie eleison,” which is the way the Old Mass says, “Lord, have mercy” (Kyrie, Kyrios, Lord, Kyrie in the vocative, Eleison, have mercy) is in Greek.

The old Mass is not so hard, really. You can have a translation on one side and the old language on the other. We used to do it that way. [Note: as in the image of the missal in Latin and English shown above.]

It’s Greek, with Aramaic, and finally it’s Latin, but still with Greek and Aramaic.

The Latin liturgy is also “Davidic.”

It’s filled with King David, much more so than the New Mass.

And in that sense, I would underline this point. Of all the poets of human history, the greatest poet was King David. His psalms are incomparable. He leaves behind Shakespeare and Dante and all the rest.

King David, with his human passion, with his fallibility, with his sins, nevertheless, was close to God and was chosen by God to be king of his people, anointed, and it was from his line that Jesus came, the son of David.

David’s words fill the old Mass.

The early part, the first 30 percent of the old liturgy, is from the psalms of King David.

That’s why I say it’s a “Hebraic” Mass.

And a “Davidic” Mass.

And a “Poetic” Mass.

The Old Mass is also dramatic. The priest begins by saying, “I will go up to the altar of God,” “Introibo ad altare Dei.”

“I will go up,” Introibo, future.

I intend to go up.

I’m going to go up to the altar of God.

And the altar boy says, “To God, who gives joy to my youth.” “Ad Deum qui laetificat juventutem meum.”

So the Mass begins with an intention to go up to the mountain, to go up to the altar.

It’s like Abraham going up to sacrifice Isaac.

It’s like Jesus going up to Golgotha.

It’s like David climbing up the hill in Jerusalem to become king.

And then the priest says, “Wait a minute. I can’t go. I am a sinful man. And what I’m about to do is enter into the presence of God — and anyone who’s sinful cannot go, not because God doesn’t appreciate and forgive sinners, but because sinners die in the presence of God, in some either metaphorical or real sense. Therefore, I can’t go up to the altar. I have to be cleansed. I have to be forgiven. I’ve got big problems.”

“O Lord, have mercy.” “Kyrie eleison.”

“O Lord, I confess to you and to my brothers and sisters that I have sinned exceedingly in thought word and deed, mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa. It’s in the ablative, “by my fault” or “through my fault,” “mea,” me, “culpa,” fault.

Mea culpa, mea maxima culpa, through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault.

So the priest is saying all this, and we, not as spectators, but as participants, participate along with him in this decision to go up and make the sacrifice.

And he is, in a sense, anonymous, not a protagonist. We don’t even have to know his name.

What we know is he’s every man, every man who wants to set out towards God, that priest, making that journey, trying to cleanse himself before God.

This is dramatic.

Now, I’m not saying there isn’t drama also in the New Mass, but it’s simpler. It’s reduced. It’s abridged.

The new Mass eliminates all of the gnarly, and I would say poetic, and I would say even extravagant, imagery and gesture of the old Mass.

[Part 8 to follow]

Facebook Comments