October 2, 2012, Tuesday — Face to Face: The Butler and the Papal Secretary Testify

But mysteries about the “Vatileaks” remain…

===============

Today the “iconic moment” occurred.

There they were, face to face, in a small Vatican courtroom (photo below — the defendant, Paolo Gabriele, the Pope’s disloyal butler, is in the middle, against the wall, in a grey suit; the papal secretary is not yet in the courtroom).

But the two never exchanged glances… never looked into each other’s eyes.

This morning Paolo Gabriele, 46, the Pope’s former butler, on trial in the Vatican on a charge that he stole sensitive Vatican documents, came face to face with the man who in May (by a process of exclusion) unmasked him as the source of at least some of the “Vatileaks” documents (Gabriele has already admitted this much) — Monsignor Georg Gaenswein, 56, the personal secretary of Pope Benedict XVI.

Gabriele rose to his feet, respectfully, when Gaenswein entered and left the room.

“A dark-faced Fr. Georg did not look at Gabriele in the face once whilst in the courtroom,” Giacomo Galeazzi of VaticanInsider wrote today.

(Here are the three men in better times, Paolo Gabriele in front and Monsignor Georg Gaenswein in back, accompanying Pope Benedict XVI in the “popemobile”)

Gaenswein testified about the daily routines of the papal household and the moment he began to suspect Gabriele was the source of the leaks.

He said that he realized that three documents that appeared this spring in His Holiness: The Secret Papers of Pope Benedict XVI’s could only have come from the office he shared with Gabriele and the Pope’s other private secretary.

As soon as saw this, he told the court, he asked the Pope’s permission to question members of the small papal family over the leaked documents.

Cristina Cernetti, one of the four consecrated lay women who work in the 85-year-old pontiff’s household, testified that she knew immediately that Gabriele was responsible.

She told the court that she could exclude all the other members of the papal family.

Three Vatican gendarmes — Giuseppe Pesce, Gianluca Gauzzi Broccoletti, and Costanzo Alessandrini — testified today about what they found when they raided Paolo Gabriele’s home in May (see below).

Gaenswein said that, among the papers sequestered in Gabriele’s home at the end of May “I saw both photocopies and originals; the earliest originals dated back to the beginning of his service (in 2006)… I saw both copies and originals from the years prior to 2010, from 2006, 2007, 2008.”

This means that Gabriele was collecting documents for years, from the very beginning of his service. And this raises the question of whether, from 2006 to 2012, he ever shared any of the documents with anyone else (any group, or government, or intelligence service) prior to sharing them in 2012 with Gianluigi Nuzzi, the author of the book that came out in May and launched this complex case into the headlines.

The trial will resume tomorrow at 9 am with testimony from four other Vatican policemen — Luca Cintia, Stefano de Santis, Silvano Carli and Luca Bassetti.

Then the trial will (most probably) go into recess on Thursday, October 4 (the day the Pope travels to Loreto).

It is widely believed that the trial will then conclude with just two more sessions, on Friday and Saturday, October 5 and 6, and the final verdict.

==============================

Three Issues, Three Puzzles

Three issues emerged with particular force this morning.

(1) The treatment of Gabriele in prison. Were the conditions of Gabriele’s imprisonment after his May 23 arrest inhumane, unworthy of the Vatican and of the Church? Or is this a “non-issue,” an exaggeration by Gabriele and his lawyer?

(2) Accomplices. Even after all these months, it is unclear: Was there a wider “Vatileaks” conspiracy? Did Gabriele act on his own, or with the help of others? Testimony today was inconclusive, but the names of several others in the Vatican who were at least on speaking terms with Gabriele were introduced into the public record, some for the first time.

(3) Motive. Why did Gabriele collect these documents? Some evidence introduced today spoke, or seemed to speak, to this question. One interesting “tidbit” of this type that has not received much attention is the revelation that Gabriele kept a huge archive — evidently hundreds and hundreds of articles and books — on freemasonry and on espionage, and the technique and practice of spying. The archive was discovered in Gabriele’s Vatican City State home when Vatican police searched it in late May. What influence did Gabriele’s study of freemasonry and espionage have on his actions?

=========================

1. “Guantanamo” on the Tiber?

Was Gabriele mal-treated during his imprisonment by Vatican officials?

The accused papal butler surprised everyone this morning when he testified that his treatment had been cruel.

He was held for the first 20 days of his imprisonment in a very small cell — not even large enough, he said, for his to stretch his arms out fully.

No measurement of the cell has ever been given, but a man’s outstretched arms reach approximately two yards (outstretched arms are usually almost the same measurement as a person’s height), so Gabriele was saying that his room was less than 6 feet wide. That’s pretty small…

Moreover, Gabriele said, a light in this cell was kept lit around the clock, 24 hours per day. This eventually caused damage to his eyesight, Gabriele stated. There was no switch for him to turn the light off, he said.

“For the first 15-20 days the light was on 24 hours a day and there was no switch,” Gabriele told the court. “As a result my eyesight was damaged.”

Not even a pillow…

On his first night in the “secure room” in the Gendarmerie barracks, “even a pillow was denied me,” he said.

After those first three weeks, he said, he was transferred into a different and larger cell.

The Vatican police force, which consists of 130 officers, all from Italy, quickly issued a statement at about midday today to say that Gabriele had not been badly treated.

His cell was small, yes, but no other room was available for those first days, the police statement said.

Yes, the light was kept on 24/7 — but that was to enable the officers to observe their prisoner and make sure he did not do anything to harm himself, the police said.

Moreover, Gabriele was given a thick eye-mask so that he could shield his eyes from the glare and sleep in full darkness, the police statement added.

The allegations of cruel treatment were picked up in the Italian and world press today.

“Paolo Gabriele trial: Former butler was ‘mistreated’,” the BBC reported.

“Pope’s ex-butler claims he was abused by police as he goes to trial for ‘stealing papal documents from the Vatican'”, wrote the Daily Mail of London.

“Vatican orders probe of police for ‘abuse’ of Pope’s butler after arrest,” was the headline in the Telegraph.

But the truth was that Gabriele was actually given special privileges, the police said.

He was allowed to use the gendarmerie gym, to socialize with officers, many of whom he knew before his arrest, and to attend Mass.

Father Federico Lombardi, the Vatican spokesman, insisted that the size of the cell, and the conditions under which Gabriele was held, conformed to international standards. “He received very humane treatment,” he said.

No photos of the cell have been released.

========================

2. Alone, or in conspiracy?

Gabriele stated firmly today that he had “no accomplices” in gathering the secret documents, or in deciding what to do with them.

So he himself has given testimony against the hypothesis that he was part of a conspiracy.

And yet… and yet…

Any conspirator may be willing to “take a fall” — to allow all the blame to fall on himself, and shield others. So, Gabriele’s denial that he worked with others, by itself, is not proof that he acted alone.

And today, for the first time, Gabriele provided evidence in a contrary direction. He stated that he was in regular contact with several senior Vatican figures, including, especially, two cardinals, Paolo Sardi and Angelo Comastri, and with Ingrid Stampa, a German woman who is a trusted confidante of the Pope and employed in his household, and whose residence happens to be in the same building as Gabriele’s residence. (So the Gabriele family and Stampa are close neighbors.)

However — and this is an intersting point — as Gabriele tried, in his testimony, to recount details of his “network” of contacts, he was repeatedly interrupted by the judge, Giuseppe Dalla Torre.

This is one of the strange things about this case: there has been an expressed desire by Vatican officials to “get to the bottom of it,” but, at different stages of the investigation, and now of the trial, there seems to be a desire to contain the case within pre-determined limits — to not “get to the bottom of it.”

To take another example: Gabriele said today that he made two copies of every secret document during office hours, in plain view of his superiors — he shared his small office with the Pope’s two private secretaries, in the Apostolic Palace.

But on Saturday, when his lawyer asked to have an office plan inserted into the trial record (evidently to help support the argument that Gabriele did everything out in the open, that he did not steal anything surreptitiously, like creep into the Vatican at 3 in the morning and, in the darkened hallways, click pictures of documents with an Iphone), the judge overruled the request and refused to allow the office plan to be entered as evidence.

Moreover, Gabriele testified today that, when he made the two copies of each document, he gave one copy to his “confessor.”

Well, this “confessor” remains a mystery figure. He is identified only as “Padre Giovanni.” He is said to have burned the entire stack of documents after he realized that they had been stolen. Why is this person not identified and asked to testify? Would that not be one more “loose end” of this case to tie up, if the Vatican is truly to “get to the bottom” of it?

So, Paolo insisted in court today that he acted totally on his own, alone.

But he then immediately added that he had “many contacts” in the Vatican, where there was “widespread unease.”

This sounds like Gabriele had to have engaged at least in conversations with these “contacts” (to hear them express their unease).

Therefore, during such conversations, these people may also have advised Gabriele to do something with the documents he was collecting — like hand them over to a journalist for publication. (In fact, we have no clarity on how Gabriele got in touch with Nuzzi, the author of the book on the secret documents. How did the two make contact? Who brought them together? We don’t know.)

The Vatican’s Promotor of Justice, Judge Nicola Picardi, asked Gabriele if these “uneasy” people in the Vatican had just chatted with him, or actually “collaborated” with him.

Gabriele replied that that “reconstruction” of the alternatives was inadequate, but he denied that anyone collaborated with him.

Still, regarding these “contacts” who did not “collaborate” with Gabriele, would it not make sense to have public testimony from some of them? Are any being called to the stand? No, not one…

“I was looking for someone in a position of authority to whom I could let off steam in confidence,” Gabriele told the court today. “The situation inside the Vatican had become intolerable — not only to me. There were many other people who felt the same way as I did.”

What “intolerable” situation Gabriele is referring to? We do not learn more.

We do know, however, that Gabriele, speaking in January on an Italian television program (his face was covered and his voice scrambled so he would not be identified, but it is now known that it was him) referred, among other things, to the case of the murder of the Commandant of the Swiss Guard on May 4, 1998. On that night, Alois Estermann, along with his wife, Gladys, were shot to death in their home in the Swiss Guard barracks, allegedly by the young Swiss Guard Cedric Tornay, who then in turn is said to have commited suicide. Gabriele said in January, evidently referring to thsat incident, that the Vatican is a place where “you can commit a murder and then disappear into the void.” So we gather that Gabriele — sho, we should not forget, was at the very side of the Pope for the past six years — has his doubts about the Vatican’s official interpretation of the events of May 4, 1998.

This morning, as Gabriele was beginning to explain in more detail why he felt Pope Benedict was not sufficiently informed about “certain matters,” the president of the three-man tribunal again stopped him.

This was not relevant to the charge of aggravated theft, the judge said.

Gabriele also said during his testimony: “I was not the only one over a period of years to provide documents to the press.”

This sounds like others in the Vatican have done what Gabriele is charged with doing, but have not been caught, or prosecuted. Again, Gabriele was not asked to elaborate on this point.

===========================

3. Motive

Gabriele has pleaded “innocent” to the charge he faces.

“In relation to the accusation of aggravated theft, I declare myself innocent,” Gabriele told the court this morning.

“But I feel guilty of having betrayed the trust of the Holy Father, whom I love like a son (would love a father),” he added.

This is the point at which this trial, and this entire case, becomes odd, perplexing.

We have here a person acting in a way that seems to harm the Pope and the Church — he obtains and then allows the publication of secret documents, causing a worldwide scandal.

But this person says he has no desire at all to harm the Pope or the Church; indeed, that he loves the Pope “like a son.”

How are we to understand this apparent paradox?

One way would be to propose this hypothesis: that Gabriele was in some way “advised” to act in this way, by others whom he trusted.

That is, that he was part of a larger group, a current or party inside the Vatican, a group of “conspirators” — literally, people “animated by one breath” or “one spirit,” people “breathing together” — and did not act alone. (Of course, another hypothesis would be that Gabriele is not telling the truth, that he does not love the Pope, but hoped to gain wealth, or fame, or something else, from this action; or even that he is mentally unstable, as some in Rome have whispered, and written, so that any attempt to attribute a reasonable motive to him would be a priori doomed to failure.)

But the thesis of a conspiracy is a thesis that seems to be excluded by everyone involved in the trial — almost as if the very word is “taboo.”

Among the thousands of pages of documents found in his home, “very many concerned freemasonry and secret services,” one of the Vatican police officers testified in court today.

Also found were manuals with instructions for how to keep someone under surveillance and follow them through a city. There were also dossiers on the internal workings of the Vatican police, and on the disappearance of Emanuela Orlandi, a 15-year-old girl, daughter of a Vatican resident, who disappeared without a trace in 1983 and has never been heard from again.

==========================

The second day of the trial, Tuesday, October 2, 2012

Here is the clear CNS report on what happened at the first hearing in this trial, which took place Tuesday morning, October 2:

Papal butler says he’s innocent of theft, but guilty of betraying Pope

Pope Benedict XVI’s former butler, Paolo Gabriele, seated in gray suit, is pictured during the opening of his trial at the Vatican September 29. (CNS/L’Osservatore Romano)

By Cindy Wooden and Carol Glatz

VATICAN CITY (CNS) — Paolo Gabriele, the papal butler charged with stealing and leaking papal correspondence, said he was innocent of charges of aggravated theft, but “I feel guilty for having betrayed the trust the Holy Father placed in me.”

“I loved him like a son,” Gabriele said of the Pope during the second day of his trial.

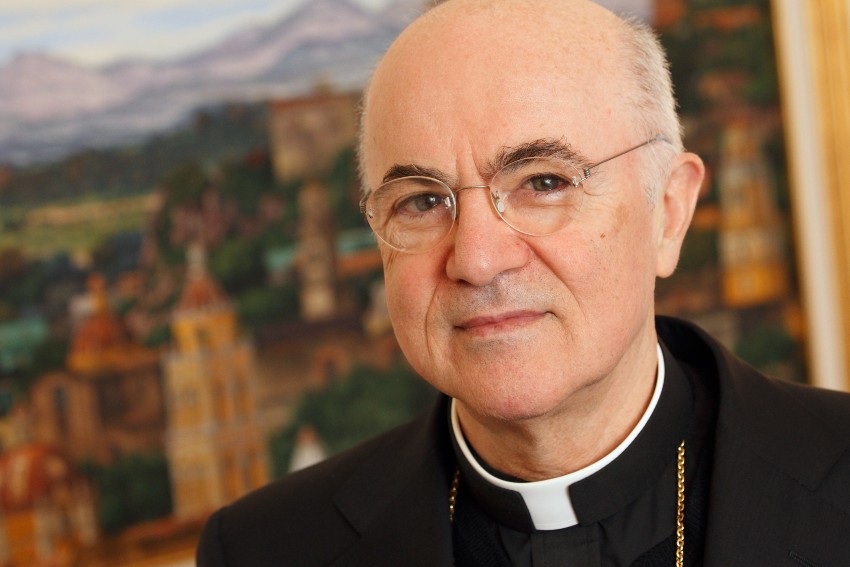

The morning session of the trial October 2 also featured brief testimony by Cristina Cernetti, one of the consecrated laywomen who work in the papal apartment; and longer testimony by Msgr. Georg Ganswein, Pope Benedict XVI’s personal secretary.

Msgr. Ganswein, who described himself as “extremely precise,” said he never noticed any documents missing, but when he examined what Vatican police had confiscated from Gabriele’s Vatican apartment, he discovered both photocopies and originals of documents going back to 2006, when Gabriele began working in the papal apartment.

Taking the stand first, Gabriele said widespread concern about what was happening in the Vatican led him to collect photocopies of private papal correspondence and, eventually, to leak it to a journalist.

“I was looking for a person with whom I could vent about a situation that had become insupportable for many in the Vatican,” he testified October 2.

Gabriele told the court that no one encouraged him to steal and leak the documents.

Although he said he acted on his own initiative, Gabriele told the court he did so after “sharing confidences” about the “general atmosphere” in the Vatican with four people in particular: retired Cardinal Paolo Sardi, a former official in the Vatican Secretariat of State; Cardinal Angelo Comastri, archpriest of St. Peter’s Basilica; Ingrid Stampa, a longtime assistant to Pope Benedict XVI, going back to his time as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger; and Bishop Francesco Cavina of Carpi, who worked in the Secretariat of State until 2011.

Gabriele said that although he had set aside some documents previously, he began collecting them seriously in 2010 after Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano, then secretary-general of Vatican City State, was reported to have run into resistance in his attempt to bring spending under control and bring transparency to the process of granting work contracts to outside companies. The archbishop is now nuncio, or ambassador, to the United States.

Asked to describe his role in the papal household, Gabriele said he served Pope Benedict his meals, informed the Vatican Secretariat of State of the gifts given to the pope, packed the Pope’s suitcases and accompanied him on trips, and did other “small tasks” assigned to him by Msgr. Ganswein.

“I was the layman closest to the Holy Father, there to respond to his immediate needs,” Gabriele said.

Being so close to the Pope, Gabriele said he became aware of how “easy it is to manipulate the one who holds decision-making power in his hands.”

Gabriele had told investigators that he had acted out of concern for the Pope, who he believed was not being fully informed about the corruption and careerism in the Vatican. Under questioning by his lawyer, he said he never showed any of the documents to the Pope, but tried — conversationally — to bring some concerns to the Pope’s attention.

The Vatican prosecutor objected to any further questioning about Gabriele’s motives, saying they “don’t matter, we must discuss the facts.”

The judges agreed and ordered the defendant’s lawyer to move on.

Gabriele’s lawyer also asked him several questions about the 60 days he spent in Vatican detention, including whether or not it was true that he first was held in a tiny room and that, for the first 15-20 days, the Vatican police left the lights on 24 hours a day. Gabriele said both were true.

Jesuit Father Federico Lombardi, Vatican spokesman, later told reporters that Judge Nicola Picardi, the Vatican prosecutor, had opened an investigation into the conditions under which Gabriele was detained.

Vatican investigators had said they found in Gabriele’s Vatican apartment three items given to Pope Benedict as gifts: a check for 100,000 euros ($123,000); a nugget — presumably of gold — from the director of a gold mining company in Peru; and a 16th-century edition of a translation of the Aeneid.

Gabriele denied the nugget was ever in his apartment, and he said he had no idea how the check got there. As for the book, he said it was normal for him to take home books given to the Pope to show his children.

“I didn’t know its value,” and, in fact, he carried it around in a plastic bag, he said.

Msgr. Ganswein testified that he only began suspecting Gabriele in mid-May after a journalist published documents Msgr. Ganswein knew had never left the office he shared with Gabriele.

When Msgr. Ganswein entered the courtroom and when he left again, Gabriele stood. He did not do so for the other witnesses.

The trial formally opened September 29 and Vatican judges decided to separate Gabriele’s trial on charges of aggravated theft from the trial of Claudio Sciarpelletti, a computer expert in the Vatican Secretariat of State, charged with aiding and abetting Gabriele.

Gabriele was arrested in May after Vatican police found papal correspondence and other items in his Vatican apartment; many of the documents dealt with allegations of corruption, abuse of power and a lack of financial transparency at the Vatican.

The papal valet — who is 46, married and has three children — faces up to four years of jail time, which he would serve in an Italian prison.

Facebook Comments