The Debate over Vatican II Continues

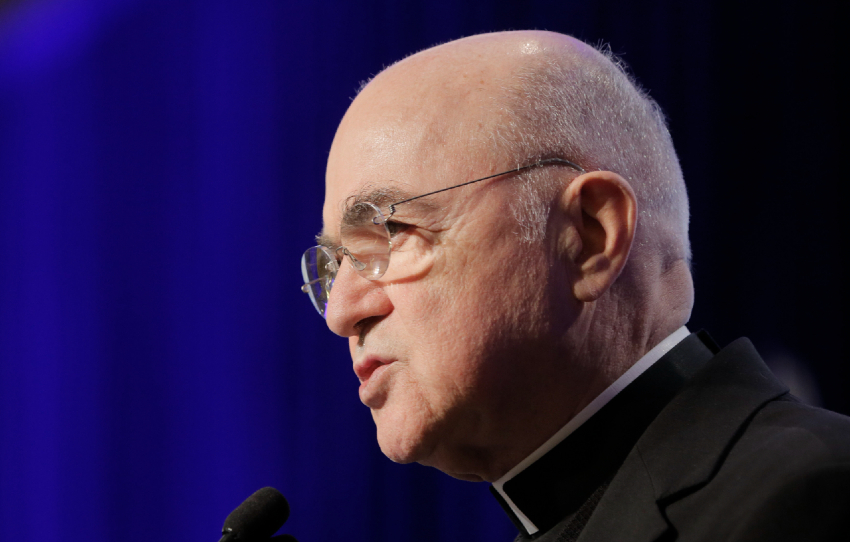

The recent intense debate over the Second Vatican Council, launched in early June by Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò (link), engaged in since by a number of Catholic scholars, is still continuing after more than three months.

Today’s letter includes:

(1) a June 29 response to Viganò by Dr. Peter Kwasniewski, an American Catholic deeply attached to the tradition of the Church, published at OnePeterFive on June 29 (link), and

(2) a new reflection by Viganò himself, dated today, September 21, expanding upon Dr. Kwasniewski’s reflections.

There are some who would argue (and have argued to me, in emails and in conversations) that any such discussion of Vatican II is likely to be “divisive” and could lead over time to the loss of Church unity — even to schism.

If such a debate would lead to the loss of Church unity, to schism, that would be tragic. We must always act in such a way as to keep the unity of the Church. But is not an open discussion of disputed questions the best way to preserve unity?

One of the four distinguishing marks of the Catholic Church, of course, is such unity, that the Church be “one.”

As the Creed expresses it, the unity of the Church is actually her first distinguishing mark: the Church is, we profess, “one, holy, catholic and apostolic.”

That means that we believe the Catholic Church, founded by Christ, cannot be split into contending factions, but must be united (“one“).

And it means the Church must not become corrupt or immoral in her conduct and teachings, remaining always upright and righteous through the righteousness of Christ (“holy”). (For this reason, we say the Church is “always” in need of reform, “semper reformanda.”)

And it means the Church is not present only in one place, one country, but is present throughout the world, everywhere (the literal meaning of the word “catholic“).

And it means that the Church does not embrace recent or “trendy” or “modern” teachings and beliefs, but always holds fast to the teaching of the Apostles, handed down from the beginning, now almost 2000 years ago (“apostolic“).

So the Church is no longer herself when she is not one, not holy, not everywhere (catholic), not apostolic.

But how is the Church’s unity, holiness, catholicity and apostolicity maintained?

These characteristics are maintained, with the help of the Holy Spirit, through the love, compassion and mutual forgiveness which bind the brothers and sisters into one family of faith, and through a common commitment to protect and hand down the truths of the faith which were once handed down by Christ himself, to be guarded by his disciples and handed down, generation upon generation, to us, and by us, to the end of time.

When love grows cold, the unity of the faith can be lost, and so the unity of the Church. When we become ideological, privileging ideas over persons, slogans over simple truths, our charity grows cold.

And when the commitment to protect and hand down the truths of our faith grows feeble, when the commitment is no longer felt as something requiring all of our mind and courage to sustain, then also the unity of the faith over time can be, and is, lost.

For this reason, we have no reason to fear a debate over important matters, including over what Vatican II was and taught and how binding those teachings are. On the contrary, we would have reason to fear, in fact, if there were no longer any believers who felt strongly enough about the integrity of our doctrine to raise questions and debate them, until reasonable persons might come to a common conclusion based on the logic of the arguments made.

In this sense, I am willing to hear all of the arguments in this debate, as in others, in the hope that it leads all of us to a deeper appreciation of the truth.

And it seems a subject quite near to my own life.

I was born in the 1950s, and one of my very earliest memories was the sight of an American television news program with a journalist speaking from St. Peter’s Square. I remember his words, sonorous, from the black and white screen: “This is Winston Burdett, speaking to you from Vatican City.” What he was reporting on that absorbed the attention of our family was… the opening of the Second Vatican Council in 1962.

I was an altar boy at the time — the time before the Council, the time of the “old Mass.”

The “old Mass” did seem old — old, and venerable, majestic, mysterious, filled with allusions to God’s holiness and our blessedness if we drew close to that holiness by loving him, and loving our neighbor, repenting of sins.

I said the responses to the Latin and felt the weight of the centuries even as a child of seven. It was a weight that I felt gave all of us gathered together, Sunday after Sunday, a certain nobility of duty and purpose.

I, like all of that time, also experienced the peculiar fascination of an event, the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) which the media told us would be a “revolution” in the life of the Church, would “break the shackles” of “outmoded beliefs and practices” and so offer “new freedom” to Catholics who had “suffered for generations” under the “oppressive regime” of a “narrow-minded, medieval institution.”

But, to tell the truth, as a boy, it all seemed to me a kind of betrayal — a betrayal of our ancestors in the faith, who had held fast to the faith — as my teachers, the nuns, taught me — during the times of the Caesars, and the times of the Renaissance princes, and the times of various revolutionaries of more modern times. One of the nuns once said to me, “Listen: no matter what others may do, you always hold fast to the faith of all time.” Her face remains in my mind. Sister Rose Genevieve.

Then, what happened? After the Council, the liturgy was changed. It was not the change of the Latin to English (the vernacular), but the change of the prayers themselves. The Davidic element (the element of King David’s Psalms) seemed diminished. The sacrificial element (the element of offering up a life for others) seemed diminished. And many other things changed as well, some of little importance, some of much greater importance.

So questions about what had been decided at the Council were in my mind from the age of 10. Who decided these things, I asked myself, and why?

And I usually find it useful now to read the reflections of others, as I continue myself to try to understand what happened to the faith that my teacher urged me to “always hold fast…”

Here are two more contributions to this continuing discussion. The texts are not short, nor are they simple, so they may take some time to read through, but they set forth some of the issues that seem to me not unimportant for the future unity and fidelity of our Church. —RM

Why Viganò’s Critique of the Council Must Be Taken Seriously

By Dr. Peter Kwasniewski

June 29, 2020 (link)

Is the recent “attack” on Vatican II a “crisis moment” for traditionalists? Are we turning on a legitimate and laudable Council instead of rightly directing our ire at the inept leadership that has followed it and betrayed it?

That has been the line of conservatives for a long time: a “hermeneutic of continuity” combined with strong criticism of episcopal and clerical brigandage. The implausibility of this approach is demonstrated by, among other signs, the infinitesimal success that conservatives have had in reversing the disastrous “reforms,” trends, habits, and institutions established in the wake of and in the name of the last council, with papal approbation or toleration. One is reminded of a secular parallel: the barren wasteland of American political “conservatism,” in which any remaining conformity of human laws and court decisions to the natural law is evaporating before our eyes.

What Archbishop Viganò has recently been saying with a forthrightness unusual in today’s prelates (see here, here, and here) is but a new installment of a longstanding critique offered by traditional Catholics, from Michael Davies’s Pope John’s Council and Romano Amerio’s Iota Unum to Roberto de Mattei’s The Second Vatican Council: An Unwritten Story and Henry Sire’s Phoenix from the Ashes. We have watched bishops, episcopal conferences, cardinals, and popes construct a “new paradigm,” piece by piece, for more than half a century — a “new” Catholic faith that at best only partially overlaps and at worst downright contradicts the traditional Catholic faith as we find it expressed in the Church Fathers and Doctors, the earlier councils, and hundreds of traditional catechisms, not to mention the old Latin liturgical rites that were suppressed and replaced with radically different ones.

So enormous a chasm gapes between old and new that we cannot refrain from asking about the role played by the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council in the unfolding of a modernist story that has its beginning in the late 19th century and its denouement in the present. The line from Loisy, Tyrrell, and Hügel to Küng, Teilhard, and (young) Ratzinger to Kasper, Bergoglio, and Tagle is pretty straight when one starts connecting the dots. This is not to say there are not interesting and important differences among these men, but only that they share principles that would have been branded as dubious, dangerous, or heretical by any of the great confessors and theologians, from Augustine and Chrysostom to Aquinas and Bellarmine.

We have to abandon once and for all the naïveté of thinking that the only thing that matters about Vatican II are its promulgated texts. No. In this case, the progressives and the traditionalists rightly concur that the event matters as much as the texts (on this point, see the incomparable book by Roberto de Mattei). The vagueness of purpose for which the Council was convened; the manipulative way it was conducted; the consistently liberal way in which it was implemented, with barely a whimper from the world’s episcopacy — none of this is irrelevant to interpreting the meaning and significance of the Council texts, which themselves exhibit novel genres and dangerous ambiguities, not to mention passages that have all the traits of flat-out error, like the teaching on Muslims and Christians worshiping the same God, of which Bishop Athanasius Schneider gave a devastating critique in Christus Vincit [see synopsis here].

It’s surprising that, at this late stage, there would still be defenders of the Council documents, when it is clear that they lent themselves exquisitely to the goal of a total modernization and secularization of the Church. Even if their content were unobjectionable, their verbosity, complexity, and mingling of obvious truths with head-scratching ideas furnished the perfect pretext for the revolution. This revolution is now melted into these texts, fused with them like metal pieces passed through a superheated oven.

Thus, the very act of quoting Vatican II has become a signal that one wishes to align with all that has been done by the popes — yes, by the popes! — in its name. At the forefront is the liturgical destruction, but examples could be multiplied ad nauseam: consider such dismal moments as the Assisi interreligious gatherings, the logic of which John Paul II defended exclusively in terms of a string of quotations from Vatican II. The pontificate of Francis has merely stepped on the accelerator.

Always it is Vatican II that is trotted out to explain or justify every deviation and departure from the historic dogmatic Faith. Is all this purely coincidental — a series of remarkably unfortunate interpretations and wayward judgments that an honest reading of the texts could dispel, like the sun blazing through the rainclouds?

Aren’t there good things in the documents?

I have studied and taught the documents of the Council, some of them numerous times. I know them very well. Since I am a “Great Books” devotee and have always taught for Great Books schools, my theology courses would typically begin with Scripture and the Fathers, then go into the scholastics (especially St. Thomas) and finish up with magisterial texts: papal encyclicals and conciliar documents.

I often felt a sinking of the heart when the course reached a Vatican II document, such as Lumen Gentium, Sacrosanctum Concilium, Dignitatis Humanae, Unitatis Redintegratio, Nostra Aetate, or Gaudium et Spes.

Of course — of course! — they have much that is beautiful and orthodox in them. They would never have gotten the requisite number of votes had they been flagrantly opposed to Catholic teaching.

However, they are also sprawling, unwieldy, inconsistent committee products, which needlessly complicate many subjects and lack the crystalline clarity that a council is supposed to work hard to achieve. All you have to do is look at the documents of Trent or the first seven ecumenical councils to see brilliant examples of this tightly constructed style, which cut off heresy at every possible point, to the extent the council fathers were capable of at that particular juncture [1]. And then there are the sentences in Vatican II — not a few of them — at which ones stops and says: “Really? Am I really seeing these words on the page in front of me? What a [messy; problematic; proximate-to-error; erroneous] thing to say” [2].

I used to hold, with conservatives, that we should “take what’s good in the Council and leave behind the rest.” The problem with this approach is captured by Pope Leo XIII in his Encyclical Satis Cognitum:

The Arians, the Montanists, the Novatians, the Quartodecimans, the Eutychians, certainly did not reject all Catholic doctrine: they abandoned only a certain portion of it. Still, who does not know that they were declared heretics and banished from the bosom of the Church? In like manner were condemned all authors of heretical tenets who followed them in subsequent ages. “There can be nothing more dangerous than those heretics who admit nearly the whole cycle of doctrine, and yet by one word, as with a drop of poison, infect the real and simple faith taught by our Lord and handed down by Apostolic tradition” (Anon., Tract. de Fide Orthodoxa contra Arianos).

In other words: it is the mixture, the jumble, of great, good, indifferent, bad, generic, ambiguous, problematic, erroneous, all of it at enormous length, that makes Vatican II uniquely deserving of repudiation [3].

Weren’t there always problems after Church Councils?

Yes, without a doubt: Church councils have been followed by a greater or lesser degree of controversy. But these difficulties were usually in spite of, not because of the nature and content of the documents. St. Athanasius could appeal again and again to Nicaea, as to a battle ensign, because its teaching was succinct and rock-solid. The popes after the Council of Trent could appeal again and again to its canons and decrees because the teaching was succinct and rock-solid. While Trent produced a large number of documents over the course of the years in which the sessions took place (1545–1563), each document is a marvel of clarity, with not a wasted word.

At the very least, the Vatican II documents failed miserably in the Council’s purpose as explained by Pope John XXIII. He said in 1962 that he wanted a more accessible presentation of the Faith for Modern Man.™ By 1965, it had become painfully obvious that the sixteen documents would never be something you would just gather into a book and hand out to every layman or inquirer. One might say the Council fell between two stools: it produced neither an accessible point of entry for the modern world nor a succinct “plan of engagement” for pastors and theologians to rely upon. What did it accomplish? A huge amount of paperwork, a lot of windy prose, and a winky nudge: “Adapt to the modern world, boys!” (Or, if you don’t, get in trouble with — to borrow a phrase from Hobbes — “the irresistible power of the mortal god” in Rome, as Archbishop Lefebvre quickly discovered.)

This is why the last council is absolutely irrecoverable. If the project of modernization has resulted in a massive loss of Catholic identity, even of basic doctrinal competence and morals, the way forward is to pay one’s last respects to the great symbol of that project and see it buried. As Martin Mosebach says, true “reform” always means a return to form — that is, a return to stricter discipline, clearer doctrine, fuller worship. It does not and cannot mean the opposite.

Is there anything of the substance of the Faith, or anything of indisputable benefit, that we would lose were we to bid the last council goodbye and never hear its name mentioned again? The Catholic Tradition already has within itself immense (and, especially today, largely untapped) resources for dealing with every vexing question we face in today’s world. Now, almost a quarter of the way into a different century, we are at a very different place, and the tools we need are not those of the 1960s.

What, then, can be done in the future?

Ever since Archbishop Viganò’s June 9 letter and his subsequent writing on the subject, people have been discussing what it might mean to “annul” the Second Vatican Council.

I see three theoretical possibilities for a future pope.

- He could publish a new Syllabus of Errors (as Bishop Schneider proposed all the way back in 2010) that identifies and condemns common errors associated with Vatican II while not attributing them explicitly to Vatican II: “If anyone says XYZ, let him be anathema.” This would leave open the degree to which the Council documents actually contain the errors; it would, however, close the door to many popular “readings” of the Council.

- He could declare that, in looking back over the past half-century, we can see that the Council documents, on account of their ambiguities and difficulties, have caused more harm than good in the life of the Church and should, in the future, no longer be referenced as authoritative in theological discussion. The Council should be treated as a historic event whose relevance has passed. Again, this stance would not need to assert that the documents are in error; it would be an acknowledgment that the Council has shown itself to be “more trouble than it’s worth.”

- He could specifically “disown” or set aside certain documents or parts of documents, even as parts of the Council of Constance were never recognized or were repudiated.

The second and third possibilities stem from a recognition that the Council took the form, unique among all ecumenical councils in the history of the Church, of being “pastoral” in purpose and nature, according to both John XXIII and Paul VI; this would make its setting aside relatively easy. To the objection that it still, perforce, concerns matters of faith and morals, I would reply that the bishops never defined anything and never anathematized anything. Even the “dogmatic constitutions” establish no dogma. It is a curiously expository and catechetical council, which settles almost nothing and unsettles a great deal.

Whenever and however a future pope or council deals with this thoroughly entrenched mess, our task as Catholics remains what it has always been: to hold fast to the Faith of our fathers in its normative, trustworthy expressions, namely, the lex orandi of the traditional liturgical rites of East and West, the lex credendi of the approved Creeds and the consistent witness of the universal ordinary Magisterium, and the lex vivendi shown to us by the saints canonized over the centuries, before the era of confusion set in. This is enough, and more than enough.

Footnotes

[1] It is noteworthy that John XXIII had appointed preparatory commissions that produced short, tight, clear documents for the upcoming council to work with — and then allowed the liberal or “Rhine” faction of council fathers to chuck out these drafts and replace them with new ones. The only exception was Sacrosanctum Concilium, Bugnini’s project, which sailed through without much trouble.

[2] It’s not just a matter of poor translations; the very first translations were generally good, and then later translations dumbed the texts down.

[3] As Cardinal Walter Kasper admitted in an article published in L’Osservatore Romano on April 12, 2013: “In many places, [the Council Fathers] had to find compromise formulas, in which, often, the positions of the majority are located immediately next to those of the minority, designed to delimit them. Thus, the conciliar texts themselves have a huge potential for conflict, opening the door to a selective reception in either direction.”

Dr. Peter Kwasniewski, Thomistic theologian, liturgical scholar, and choral composer, is a graduate of Thomas Aquinas College and The Catholic University of America. He has taught at the International Theological Institute in Austria; the Franciscan University of Steubenville’s Austria Program; and Wyoming Catholic College, which he helped establish in 2006. Today he is a full-time writer and speaker on traditional Catholicism, writing regularly for OnePeterFive, New Liturgical Movement, LifeSiteNews, and other websites and print publications. He has published eight books, the most recent being Reclaiming Our Roman Catholic Birthright: The Genius and Timeliness of the Traditional Latin Mass (Angelico, 2020). Visit his website at www.peterkwasniewski.com.

Dr. Peter Kwasniewski, Thomistic theologian, liturgical scholar, and choral composer, is a graduate of Thomas Aquinas College and The Catholic University of America. He has taught at the International Theological Institute in Austria; the Franciscan University of Steubenville’s Austria Program; and Wyoming Catholic College, which he helped establish in 2006. Today he is a full-time writer and speaker on traditional Catholicism, writing regularly for OnePeterFive, New Liturgical Movement, LifeSiteNews, and other websites and print publications. He has published eight books, the most recent being Reclaiming Our Roman Catholic Birthright: The Genius and Timeliness of the Traditional Latin Mass (Angelico, 2020). Visit his website at www.peterkwasniewski.com.

The Reflection of Archbishop Viganò on Kwasniewski’s Essay

By Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò

September 21, 2020

Peter Kwasniewski’s recent commentary, titled “Why Viganò’s critique of the Council must be taken seriously”, impressed me greatly. It appeared (here) on One Peter Five, on June 29, and is one of the articles on which I have been meaning to comment: I do so now, with gratitude to the author and publisher for the opportunity they have given me.

First, it seems to me that I can agree with practically all of what Kwasniewski has written: his analysis of the facts is extremely clear and polished and reflects my thoughts exactly. What I am particularly pleased about is that “ever since Archbishop Viganò’s June 9 letter and his subsequent writing on the subject, people have been discussing what it might mean to ‘annul’ the Second Vatican Council”.

I find it interesting that we are beginning to question a taboo that, for almost sixty years, has prevented any theological, sociological and historical criticism of the Council. This is particularly interesting given that Vatican II is regarded as untouchable, but this does not apply – according to its supporters – to any other magisterial document or to Sacred Scripture. We have read endless addresses in which the defenders of the Council have defined the Canons of Trent, the Syllabus of Errors of Blessed Pius IX, the encyclical Pascendi of St. Pius X, and Humanae Vitae and Ordinatio Sacerdotalis of Paul VI as “outdated.” The change to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, whereby the doctrine on the legitimacy of the death penalty was modified in the name of a “changed understanding” of the Gospel, shows that for the Innovators there is no dogma, no immutable principle that can be immune from revision or cancellation: the only exception is the Vatican II, which by its nature – ex se, theologians would say – enjoys that charism of infallibility and inerrancy that is denied to the entire depositum fidei.

I have already expressed my opinion on the hermeneutic of continuity theorized by Benedict XVI, and constantly taken up by the defenders of Vatican II, who – certainly in good faith – seek to offer a reading of the Council that is harmonious with Tradition. It seems to me that the arguments in favor of the hermeneutical criterion, proposed for the first time in 2005 [link], are limited to a merely theoretical analysis of the problem, obstinately leaving aside the reality of what has been happening before our eyes for decades. This analysis starts from a valid and acceptable postulate, but in this concrete case, it presupposes a premise that is not necessarily true.

The postulate is that all the acts of the Magisterium are to be read and interpreted in the light of the entire magisterial corpus, because of the analogia fidei [1] [analogy of faith], which is somehow also expressed in the hermeneutic of continuity. Yet this postulate assumes that the text we are going to analyze is a specific act of the Magisterium, with its degree of authority clearly expressed in the canonical forms envisaged. And this is precisely where the deception lies, this is where the trap is set. For the Innovators maliciously managed to put the label “Sacrosanct Ecumenical Council” on their ideological manifesto, just as, at a local level, the Jansenists who maneuvered the Synod of Pistoia had managed to cloak with authority their heretical theses, which were later condemned by Pius VI. [2]

On the one hand, Catholics look at the form of the Council and consider its acts to be an expression of the Magisterium. Consequently, they seek to read its substance, which is clearly ambiguous or even erroneous, in keeping with the analogy of faith, out of that love and veneration that all Catholics have towards Holy Mother Church. They cannot comprehend that the Pastors have been so naïve as to impose on them an adulteration of the Faith, but at the same time they understand the rupture with Tradition and try to explain this contradiction.

The modernist, on the other hand, looks at the substance of the revolutionary message he means to convey, and in order to endow it with an authoritativeness that it does not and should not have, he “magisterializes” it through the form of the Council, by having it published in the form of official acts. He knows well that he is forcing it, but he uses the authority of the Church – which under normal conditions he despises and rejects – to make it practically impossible to condemn those errors, which have been ratified by no less than the majority of the Synod Fathers. The instrumental use of authority for purposes opposed to those that legitimize it is a cunning ploy: on the one hand, it guarantees a sort of immunity, a “canonical shield” for doctrines that are heterodox or close to heresy; on the other hand, it allows sanctions to be imposed on those who denounce these deviations, by virtue of a formal respect for canonical norms.

In the civil sphere, this way of proceeding is typical of dictatorships. If this has also happened within the Church, it is because the accomplices of this coup d’état have no supernatural sense, they fear neither God nor eternal damnation, and consider themselves partisans of progress invested with a prophetic role that legitimizes them in all their wickedness, just as Communism’s mass exterminations are carried out by party officials convinced of promoting the cause of the proletariat.

In the first case, the analysis of the Council documents in the light of Tradition clashes with the observation that they have been formulated in such a way as to make clear the subversive intent of their drafters. This inevitably leads to the impossibility of interpreting them in a Catholic sense, without weakening the whole doctrinal corpus. In the second case, the awareness that doctrinal novelty that was being slipped into the acts of the Council made it necessary to formulate them in a deliberately ambiguous manner, precisely because it was only in making people believe that they were consistent with the Church’s perennial Magisterium that they could be adopted by the authoritative assembly that had to “clear” and circulate them.

It ought to be highlighted that the mere fact of having to look for a hermeneutical criterion to interpret the Council’s acts demonstrates the difference between Vatican II and any other Ecumenical Council, whose canons do not give rise to any sort of misunderstanding. An unclear passage from Sacred Scripture or from the Holy Fathers can be the object of a hermeneutic, but certainly not an act of the Magisterium, whose task is precisely to dispel any lack of clarity. Yet both conservatives and progressives find themselves unwittingly in agreement in recognizing a kind of dichotomy between what a Council is and what that Council – i.e. Vatican II – is; between the doctrine of all Councils and the doctrine set forth or implied in that Council.

Archbishop Guido Pozzo, in a recent commentary in which he quotes Benedict XVI, rightly states that “a Council is such only if it remains in the furrow of Tradition and it must be read in the light of the whole Tradition.” [link] But this statement, which is irreproachable from a theological point of view, does not necessarily lead us to consider Vatican II as Catholic, but rather to ask ourselves whether it, by not remaining in the furrow of Tradition and not being able to be read in the light of the whole Tradition, without upsetting the mens that wanted it, can actually be defined as such. This question certainly cannot be met with an impartial answer in those who proudly profess to be its supporters, defenders and creators. And I am obviously not talking about the rightful defense of the Catholic Magisterium, but only of Vatican II as the “first council” of a “new church” claiming to take the place of the Catholic Church, which is hastily dismissed as a preconciliar.

There is also another aspect that, in my view, should not be overlooked; namely, that the hermeneutical criterion – seen in the context of a serious and scientific criticism of a text – cannot disregard the concept that the text means to express. Indeed, it is not possible to impose a Catholic interpretation on a proposition that, in itself, is manifestly heretical or close to heresy, simply because it is included in a text that has been declared magisterial. Lumen Gentium’s proposition: “But the plan of salvation also includes those who acknowledge the Creator. In the first place amongst these there are the Muslims, who, professing to hold the faith of Abraham, along with us adore the one and merciful God, who on the last day will judge mankind” (LG, 16) cannot be interpreted in a Catholic way – firstly, because the god of Mohammed is not one and triune, and secondly because Islam condemns as blasphemous the Incarnation of the Second Person of the Most Holy Trinity in Our Lord Jesus Christ, true God and true Man.

To affirm that “the plan of salvation also includes those who acknowledge the Creator” and that “in the first place amongst these there are the Muslims” blatantly contradicts Catholic doctrine, which professes that the Catholic Church is the one and only ark of salvation. The salvation eventually attained by heretics, and by pagans even more so, always and only comes from the inexhaustible treasure of Our Lord’s Redemption, which is safeguarded by the Church. While belonging to any other religion is an impediment to the pursuit of eternal beatitude. Those who are saved, are saved because of at least an implicit desire to belong to the Church, and despite their adherence to a false religion – never by virtue of it. For what good it contains does not belong to it, but has been usurped; while the error it contains is what makes it intrinsically false, since the admixture of errors and truth more easily deceives its followers.

It isn’t possible to change reality to make it correspond to an ideal schema. If the evidence shows that some propositions contained in the Council documents (and similarly, in the acts of Bergoglio’s magisterium) are heterodox, and if doctrine teaches us that the acts of the Magisterium do not contain error, the conclusion is not that those propositions are not erroneous, but that they cannot be part of the Magisterium. Period.

Hermeneutics serve to clarify the meaning of a phrase that is obscure or that appears to contradict doctrine, not to correct it substantially ex post. This way of proceeding would not provide a simple key to reading the Magisterial texts, but would constitute a corrective intervention, and therefore the admission that, in that specific proposition of that specific Magisterial document, an error has been stated which must be corrected. And one would need to explain not only why that error was not avoided from the beginning, but also whether the Synod Fathers who approved that error, and the Pope who promulgated it, intended to use their apostolic authority to ratify a heresy, or whether they would rather avail themselves of the implicit authority deriving from their role as Pastors to endorse it, without calling the Paraclete into question.

Archbishop Pozzo admits: “The reason why the Council has been received with difficulty therefore lies in the fact that there has been a struggle between two hermeneutics or interpretations of the Council, which indeed have coexisted in opposition to one another.” But with these words, he confirms that the Catholic choice to adopt the hermeneutic of continuity goes hand in hand with the novel choice to resort to the hermeneutic of rupture, in an arbitrariness that demonstrates the prevailing confusion and – what is even more serious – the imbalance of the forces at play, in favor of one or the other thesis. “The hermeneutic of discontinuity risks ending in a rupture between the pre-conciliar and post-conciliar Church and presupposes that the texts of the Council as such are not the true expression of the Council, but the result of a compromise”, Archbishop Pozzo writes. But this is exactly the reality, and denying it does not resolve the problem in the slightest but rather exacerbates it, by refusing to acknowledge the existence of cancer even when it has very clearly reached its metastasis.

Archbishop Pozzo’s affirmation that the concept of religious freedom expressed in Dignitatis humanae does not contradict Pius IX’s Syllabus of Errors [3] demonstrates that the Council document is in itself deliberately ambiguous. If its drafters had wished to avoid such ambiguity, it would have been sufficient to reference the propositions of the Syllabus in a footnote; but this would never have been accepted by the progressives, who were able to slip in a doctrinal change precisely on the basis of the absence of references to the earlier Magisterium. And it doesn’t seem that the interventions of the post-conciliar Popes – and their own participation, even in sacris, in non-Catholic or even pagan ceremonies – have ever, or in any way, corrected the error propagated in line with the heterodox interpretation of Dignitatis humanae. Upon closer examination, the same method was adopted in the drafting of Amoris laetitia, in which the Church’s discipline in matters of adultery and concubinage was formulated in such a way that it could theoretically be interpreted in a Catholic sense, while in fact it was accepted in the one and obvious heretical sense they wanted to disseminate. So much so, that the interpretive key that Bergoglio and his exegetes wanted to use, on the issue of Communion for divorcees, has become the authentic interpretation in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis [link].

The aim of Vatican II’s public defenders has turned out to be the struggle of Sisyphus: as soon as they succeed, by a thousand efforts and a thousand distinctions, in formulating a seemingly reasonable solution that doesn’t directly touch their little idol, immediately their words are repudiated by opposing statements from a progressive theologian, a German Prelate, or Francis himself. And so, the conciliar boulder rolls back down the hill again, where gravity attracts to its natural resting place.

It is obvious that, for a Catholic, a Council is ipso facto of such authority and importance that he spontaneously accepts its teachings with filial devotion.

But it is equally obvious that the authority of a Council, of the Fathers who approve its decrees, and of the Popes who promulgate them, does not make the acceptance of documents that are in blatant contradiction with the Magisterium, or at least weaken it, any less problematic.

And if this problem continues to persist after sixty years revealing a perfect consistency with the deliberate will of the Innovators who prepared its documents and influenced its proponents we must ask ourselves what is the obex, the insurmountable obstacle, that forces us, against all reasonableness, to forcibly consider Catholic what is not, in the name of a criterion that applies only and exclusively to what is certainly Catholic.

One needs to keep clearly in mind that the analogia fidei applies precisely to the truths of Faith, and not to error, since the harmonious unity of the Truth in all its articulations cannot seek coherence with what is opposed to it. If a conciliar text formulates a heretical concept, or one close to heresy, there is no hermeneutical criterion that can make it orthodox simply because that text belongs to the Acts of a Council. We all know what deceptions and skillful maneuvers have been put in place by ultra-progressive consultors and theologians, with the complicity of the modernist wing of the Council Fathers. And we also know with what complicity John XXIII and Paul VI approved these coups de main (surprise attacks) in violation of the norms which they themselves approved.

The central vice therefore lies in having fraudulently led the Council Fathers to approve ambiguous texts – which they considered Catholic enough to deserve the placet – and then using that same ambiguity to get them to say exactly what the Innovators wanted. Those texts cannot today be changed in their substance to make them orthodox or clearer: they must simply be rejected – according to the forms that the supreme Authority of the Church shall judge appropriate in due course – since they are vitiated by a malicious intention. And it will also have to be determined whether an anomalous and disastrous event such as Vatican II can still merit the title of Ecumenical Council, once its heterogeneity compared to previous councils is universally recognized. A heterogeneity so evident that it requires the use of a hermeneutic, something that no other Council has ever needed.

It should be noted that this mechanism, inaugurated by Vatican II, has seen a recrudescence, an acceleration, indeed an unprecedented upsurge with Bergoglio, who deliberately resorts to imprecise expressions, cunningly formulated without precise theological language, with the same intention of dismantling, piece by piece, what remains of doctrine, in the name of applying the Council. It’s true that, in Bergoglio, heresy and heterogeneity with respect to the Magisterium are blatant and almost shameless; but it is equally true that the Abu Dhabi Declaration would not have been conceivable without the premise of Lumen gentium.

Rightly, Dr. Peter Kwasniewski states: “It is the mixture, the jumble, of great, good, indifferent, bad, generic, ambiguous, problematic, erroneous, all of it at enormous length, that makes Vatican II uniquely deserving of repudiation.” The voice of the Church, which is the voice of Christ, is instead crystal clear and unambiguous, and cannot mislead those who rely on its authority! “This is why the last council is absolutely irrecoverable. If the project of modernization has resulted in a massive loss of Catholic identity, even of basic doctrinal competence and morals, the way forward is to pay one’s last respects to the great symbol of that project and see it buried.”

I wish to conclude by reiterating a fact which, in my view, is very indicative: if the same commitment that Pastors have exerted for decades in defending Vatican II and the “conciliar church” had been used to reaffirm and defend the entirety of Catholic doctrine, or even only to promote knowledge of the Catechism of St Pius X among the faithful, the situation of the ecclesial would be radically different. But it is also true that faithful formed in fidelity to doctrine would have reacted with pitchforks to the adulterations of the Innovators and their protectors. Perhaps the ignorance of God’s people was intended, precisely so that Catholics would be unaware of the fraud and betrayal perpetrated against them, just as the ideological prejudice that weighs on the Tridentine Rite serves only to prevent it from being compared with the aberrations of the reformed ceremonies.

The cancellation of the past and of Tradition, the denial of roots, the delegitimization of dissent, the abuse of authority and the apparent respect for rules: are not these the recurring elements of all dictatorships?

+ Carlo Maria Viganò, Archbishop

September 21, 2020

St. Mathew, apostle and evangelist

Official translation from the Italian by Diane Montagna

[1] CCC, n. 114: “By ‘analogy of faith’ we mean the coherence of the truths of faith among themselves and within the whole plan of Revelation.”

[2] It’s interesting to note that, even in that case, of the 85 synodal theses condemned by the Bull Auctorem fidei, only 7 were totally heretical, while the others were defined as “schismatic, erroneous, subversive of the Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, false, reckless, temerarious, capricious, insulting the Church and its authority, leading to contempt for the Sacraments and the practices of Holy Church, offensive to the piety of the faithful, disturbing the order of the various churches, the ecclesiastical ministry, and the peace of souls; in contrast to the Tridentine decrees, offensive to the veneration due to the Mother of God, the rights of the General Councils.”

[3] “At the same time, however, Vatican II in Dignitatis humanae reconfirms that the only true religion exists in the Catholic and apostolic Church, to which the Lord Jesus entrusts the mission of communicating it to all men (DH, n.1), and thereby denies relativism and religious indifferentism, also condemned by the Syllabus of Pius IX.”

We ask you to support Urbi et Orbi Communications with a small or large contribution, at this difficult time, in order…

(1) to keep Inside the Vatican Magazine (which we have published since its founding in 1993, 27 years ago) independent and comprehensive… a unique lens into the Church and the World. Now available to you digitally as well as in print!

(2) to ensure that Inside the Vatican Pilgrimages can keep creating encounters for you with the Heart of the Churches, the homes of the Saints, and the Living Stones — the people — of whom the Church is built. Now offering you virtual pilgrimages from your home computer! (see below for more information)

(3) to helping to bring the Churches closer together by “Building Bridges” to heal the schisms of the Church — East and West — through our Urbi et Orbi Foundation.

(4) to sustain our occasional news and editorial emails, The Moynihan Letters, bringing the latest valuable information and insight like no other source to thousands of readers around the world.

Your support is important to us and much needed, especially in these difficult days of lockdown and concern about the Coronavirus.

Please, do not overlook this opportunity to work with us. We very much appreciate your gift, whether small or large.

Thank you.

In Christ,

Dr. Robert Moynihan and the rest of the Urbi et Orbi Team

Facebook Comments